ST PAUL, Minn. — As Sai Thao works in the garden dedicated to her daughter, Ghia, she thinks: “These are the things that I did.”

I stayed home with her when she was born.

I watched her grow.

When Sai and Jim Vue’s son admitted that he felt responsible for Ghia’s drowning, Jim told him:

Here are the things that you did.

You searched for her. You helped.

Sai and Jim have made this a part of their grieving process, after losing their 6-year-old daughter to the water at Lake Elmo Park Reserve three years ago. The concrete facts keep them from dwelling on what could have been or should have been. They teach their children to hold onto what was, and is.

When Sai and Jim’s daughter, Dhoua, says she misses her sister, her parents say:

You miss her because you loved her so much.

Here are all the things you did together.

These are the ways in which you loved her.

One new friend a year

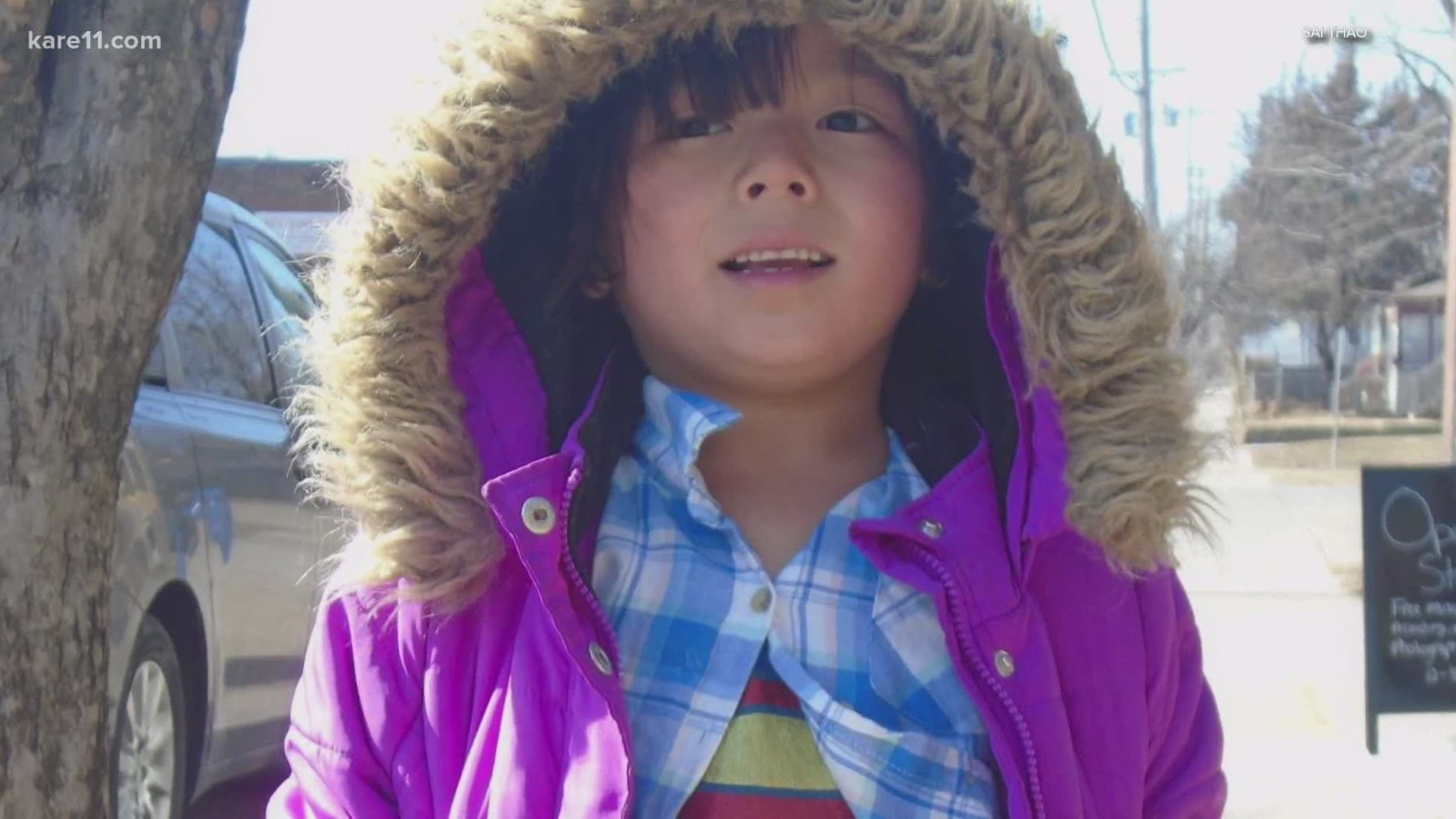

Like any child, there were some things about Ghia that her parents did not know. But after she died, they had the opportunity to find out.

“The days after Ghia’s drowning, we had people show up to our doorstep with food, people that we didn’t even know that knew Ghia or that was a part of Ghia’s life,” Sai said.

Ghia’s principal called her the “mayor” of the school.

“Because somehow, she knew everybody at the school,” Jim said, laughing. “Even the older kids on the second floor knew her.”

After Ghia died, Jim realized that she had “this whole life of friendship” that he didn’t know about.

“She touched them and she made them feel special, and that’s what I remember about Ghia,” Jim said. “She definitely made me feel that way, but I did not know the scale and the scope that she made other people feel that way.”

Jim and Sai have both tried to continue learning from Ghia. For Jim, that now means making one new friend a year. He doesn’t put pressure on himself to make as many as Ghia – but with that one new friend a year, he works hard to stay in touch and stay engaged.

For Sai, learning from Ghia means creating moments with people.

“Ghia had this thing about approaching strangers or approaching people and just having these awesome conversations, you know, these really in-depth conversations,” Sai said. “And then walking away with new knowledge or installing experiences, everlasting experiences with others.”

‘Grief is meant to be shared’

Ghia’s death was not private, like many people’s. Her family lost her in front of a crowd of onlookers. But Jim Vue said among those people staring, a few emerged to help.

It was a hot Sunday, June 4, 2017. When Ghia was found, Sai had to go with the ambulance straight to the hospital, leaving Jim with the rest of the kids.

“We brought a lot of gear and junk with us at the beach and I had to carry some of that gear back to the car and manage my children,” he said.

Two families stepped up to help Jim get all of his things, and the kids, to the car.

“It meant a lot to me that these people were able to sort of jolt themselves out of the tragedy that’s happened and sort of turn their inaction into some sort of action to help us,” he said.

This would become a theme for Sai and Jim. People who didn’t just “hope and pray,” but “who did the work of hope.”

They chose to have a Hmong funeral for Ghia. That meant their home was opened to family and friends.

“That is exhausting,” Jim said. “It takes a lot of work on our part.”

They had friends who would come and stay the whole day, cooking, cleaning, and talking about Ghia. “Being in the grief,” Jim said.

“Coming is one thing, but coming to stay and be a part of this process that we were going through, that was really helpful in understanding what hope can look like,” Sai said.

Jim said one thing he’s learned, both with Ghia’s death, and the death of his father when he was just a teenager, is that you don’t do it alone.

“You don’t carry the whole weight of the grief by yourself,” he said. “And even if you do, even if you carry the whole weight of grief by yourself, that’s not some kind of accomplishment that you should be proud of. I think grief is meant to be shared.”

It all goes back to that day at the beach, Jim said.

“What those parents who stepped up allowed me to see is I don’t have to do it myself, you know, and I’m not supposed to.”

‘Ghia lived’

Ghia loved gardens. She loved watching things grow. The first year her family had a garden, Sai planted carrots.

“She was just so in awe, you know, with the idea of a seed and how that seed grows and develops into something that she loves,” Sai said.

That fall, Sai told Ghia the carrots were ready.

“Her eyes got really big and you know, I remember her going up to the garden and just pulling up the carrots, and realizing that it had been there all along after she planted a seed.”

Sai and Jim kept up the garden after Ghia died, and then they expanded it. They planted gardens at other places she loved, like her mother’s nonprofit, In Progress. That one, now a flower garden, has sunflowers and shades of purple, red and green.

Ghia died around the time of the growing season, early summer. Her birthday was in July. The rhythm of caring for the garden helps Sai and Jim through the series of painful anniversaries.

“When I am out there in the garden, and I am planting seeds, and watching these grow, I remember how she was my daughter and I remember how - the moments that we lived, you know, and how she grew,” Sai said.

“I always go back to the part that Ghia lived. Ghia lived and she died, and I think that’s something that’s very important to note, that you can love and you can hurt at the same time.”

And so as Sai gardens, she thinks:

My daughter lived.

She grew.

Jim looks at his hands and thinks:

I helped raise her.

She would latch onto my fingers and walk with me.

Jim says, "A garden helps us remember that Ghia lived, she lived for a brief time but she lived still, she changed, and-"

Sai finishes for Jim. “It’s a reminder for us to live and continue to live.”

Ghia's little sister, Dhoua, made the below video for her sister after she died. Ghia Nah means "rainwatcher." Dhoua Hli means "moon's reflection" or "picture of the moon." Sai and Jim also shared their story in Twin Cities author Kao Kalia Yang's new illustrated book, The Shared Room.

In this series of hard times and hope, we hear from Minnesotans about the toughest time in their life – and what got them through. Would you like to tell your story? Email ehaavik@kare11.com.