UNITED STATES, — When Achsah Nesmith got the phone call offering her a job writing presidential speeches for Jimmy Carter, she turned it down. As the mother of two young children, she explained to Carter's chief of staff, she just didn't have time.

Nesmith quickly changed her mind, however, and called back to accept with encouragement from her husband, a fellow journalist who told her: “I can raise two babies.” She arrived at the White House right after Carter's 1977 inauguration, becoming one of the first women to work as a speechwriter for an American president.

“She was not one to tout her own accomplishments,” Susannah Nesmith said of her mother. “She was always careful to point out that Betty Ford had a speechwriter who wrote for President Ford. And John Adams’ wife wrote some, if not all, of his speeches.”

Nesmith, who lived in Alexandria, Virginia, died March 5 following a brief illness at age 84. She prided herself on crafting speeches that enabled Carter to sound like himself, free of political double-speak and cliches, her daughter said.

“She was one of his favorite speechwriters by far. She just had his voice," said Terry Adamson, who worked with Nesmith in the newsroom of The Atlanta Constitution before serving in the Justice Department during the Carter administration and later as Carter's personal attorney.

Carter, 99, entered hospice care a year ago at his home in Plains, Georgia, and is the longest-living U.S. president.

RELATED: A year after Jimmy Carter entered hospice care, advocates hope his endurance drives awareness

When he met Nesmith, Carter was a little-known peanut farmer running his first campaign for Georgia governor in 1966. She was a reporter for The Atlanta Constitution covering the race, which Carter lost.

“She was sometimes the only reporter on those campaign stops, because he traveled all over the state," Susannah Nesmith said in a phone interview. “So she got to know him very well. They had similar ideas, I think, about justice and about a new South that could shed its racist legacy.”

Nesmith started as an intern at the Atlanta newspaper, her daughter said, and was hired full-time after she kept coming to work after her internship had officially ended. She was assigned to cover Atlanta's federal courts as they ruled on important civil rights cases. And she wrote stories about some of the civil rights movement's key figures, including Martin Luther King Jr.

On April 5, 1968, the day after King was assassinated in Tennessee, the front page of The Atlanta Constitution included the obituary Nesmith wrote, memorializing King as the grandson of a slave whose nonviolent activism made him “one of the best known men in the world.”

“She told me she wrote that while crying,” Nesmith's daughter said.

Nesmith's rapport with Carter paid off soon after he won the presidency in 1976 and his chief of staff, Jody Powell, hired her as a speechwriter. It took some adjustment by Carter, who was used to preparing his own public remarks as Georgia governor and even wrote his own inaugural address.

Nesmith would later say their shared Georgia roots gave her an edge in writing for Carter, noting that she was the only fellow Southerner on his speechwriting staff.

“He was not a part of the Washington thinking, to some extent,” Nesmith said in a 1992 interview on C-SPAN. “He was very much inclined not to schmooze so much as to explain and then expect people to understand and then act on it.”

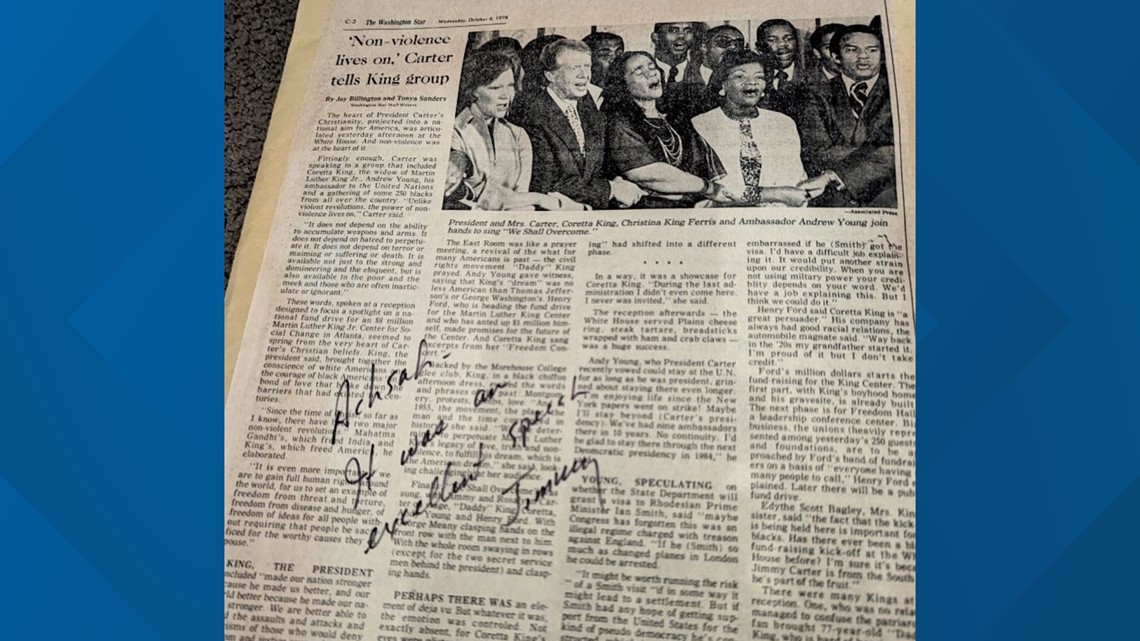

Among the newspaper clippings Nesmith kept was a full-page story from The Washington Star on a speech Carter delivered in October 1978 on King's legacy of nonviolence, which the slain civil rights leader's family attended. On the page was a handwritten note from the president: “Achsah — It was an excellent speech.”

Nesmith remained on Carter's staff until the end of his presidency. The day after he lost the 1980 election to Ronald Reagan, Nesmith dealt with the defeat by planting hundreds of daffodil bulbs in the yard of her Virginia home.

"She felt like it was the only thing she could do that would yield anything good,” her daughter said.

After they left the White House, Nesmith helped the former president and his wife, Rosalynn Carter, with their co-authored 1987 book, “Everything To Gain: Making the Most of the Rest of Your Life,” Susannah Nesmith said, and later worked with Carter on his Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech in 2002.

In the mid-1980s, Nesmith went to work for U.S. Sen. Sam Nunn, a Georgia Democrat known for his work to rein in the proliferation of nuclear weapons.

“Achsah had a quiet and caring but very strong voice, with a depth of knowledge across many areas,” Nunn said in a statement. “She was a talented and wonderful partner for those of us in the arena of public service. I was very proud to be the beneficiary of Achsah’s wonderful character, her wisdom and her sound judgment. She was able to read a room on every occasion.”

Nesmith's husband of 57 years, Jeff Nesmith, died last year. He won a Pulitzer Prize in 1998 for an investigative series on medical malpractice in the military published by the Dayton Daily News in Ohio. In addition to her daughter, Nesmith is survived by her son, Hollis Jefferson Nesmith III, two grandchildren and a niece.