ATLANTA — Meka Pless starts each day the same way she did on the morning of June 27, 2020.

“You know, I still wake up at five in the morning as if he’s here. I still cook as if he was still here,” she said.

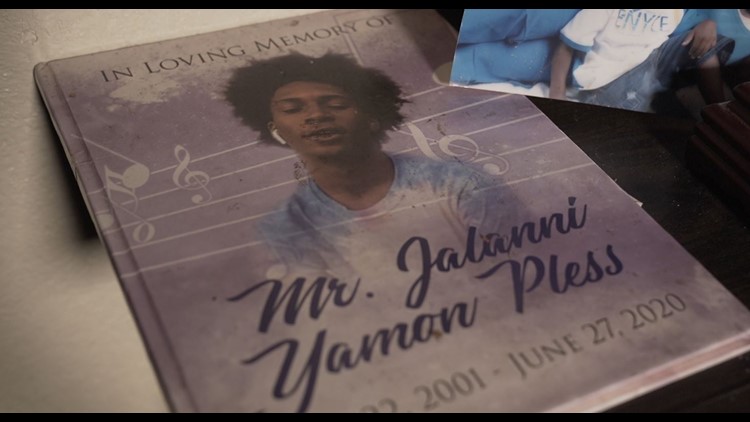

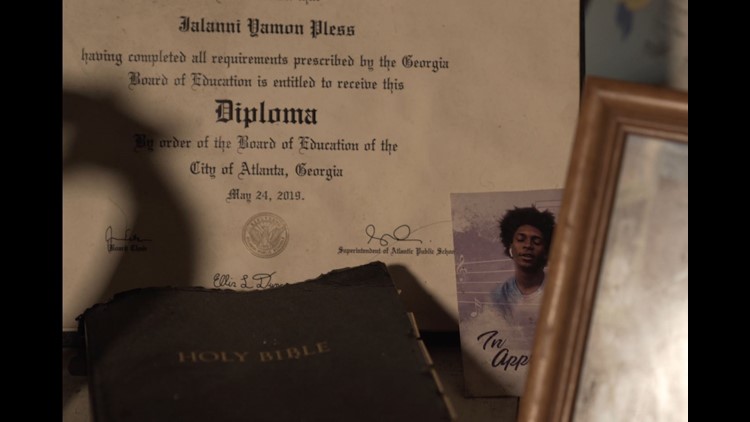

Inside of her Atlanta home, her son Jalanni -her eldest child- is the centerpiece of her family’s life. The entire apartment is decorated with his legacy, from his artifacts, yearbook photos, medals from his athletic accomplishments, and certificates. The 18-year-old’s presence is felt in the living room, even though he’s no longer here.

“Everything that I put in that backpack that day before he walked out the door is still in the bag,” Pless added.

The teen's life ended when he was shot and killed over a dispute of $10 while selling water bottles in Midtown.

“When I saw the coroner’s van come up, I knew he was gone,” Pless said, fighting back tears.

Jalanni was known for many things. Pless said her son was the love and the light of her life. She celebrated all his milestones, not knowing her son’s lifespan would be cut short.

She said her son graduated from Douglas High School and had a full-time job and a side hustle selling water bottles on the streets of Atlanta.

But everything changed when his mother received a call at 2:19 PM that June day.

Mother honors son shot, killed while selling water

‘All we can do is pray’

Time stopped for the Pless family the day they lost Jalanni.

“All we can do is pray that there’s a change, and it’s really time for a change because we’ve lost a lot of our babies,” Pless said.

His motive to sell water was no different than that of countless other Atlanta kids and teens.

According to the U.S. Census Supplemental Poverty Measure (SPM) report, the child poverty rate more than doubled last year compared to 2021. And in Atlanta, if you’re born into poverty, you have a four percent chance of escaping it, according to the Atlanta Wealth Building Initiative.

In Atlanta, young adult poverty rates remain high, according to The Annie E. Casey Foundation.

For Jalanni, the goal of selling water, on top of having a job, was to have extra funds to put towards a car and help out at home.

“No parent should have to go through what I’m going through,” Pless said.

Before he died, Jalanni was weeks shy of his 19th birthday.

‘It starts in the household’

There is nothing Pless wouldn’t have done for her son. When asked what she'd say if Jalanni could hear her now, she said, "It’s hard. I love him, and I wish he would have just come home."

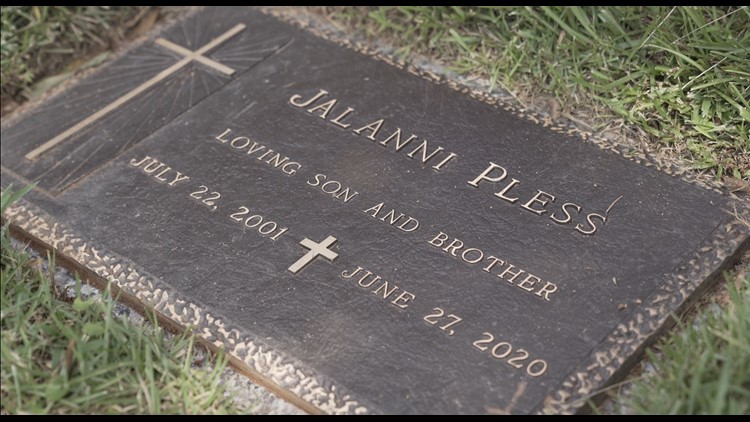

A few miles from their home, the teen's headstone rests quietly amongst trees.

“I just hate that he’s not here,” Pless said. “I had to go sit at a cemetery. I’m just looking at his headstone.”

Since Jalanni’s death, his mother has tried to push forward - honoring his legacy while raising awareness about what happened and why selling water for Atlanta youth is so much bigger than the water bottle.

But when asked about what intervention young people need, Pless remarked, "To me, it starts in the household."

She wants parents to be aware of their children selling water in Atlanta.

“I’ve been trying to start the Jalanni Bill for a while now,” she said. “Like, at first, I wanted to ban the Waterboys, but that’s how they survive. This [is] how most of them take care of their households.”

Instead, she also wants to encourage youth to find allyship amongst the hustle of a water bottle sale.