ATLANTA — Artist Basil Watson stared long and hard at his creation, sculpted during a time of pandemic, social tension, and turmoil in Atlanta.

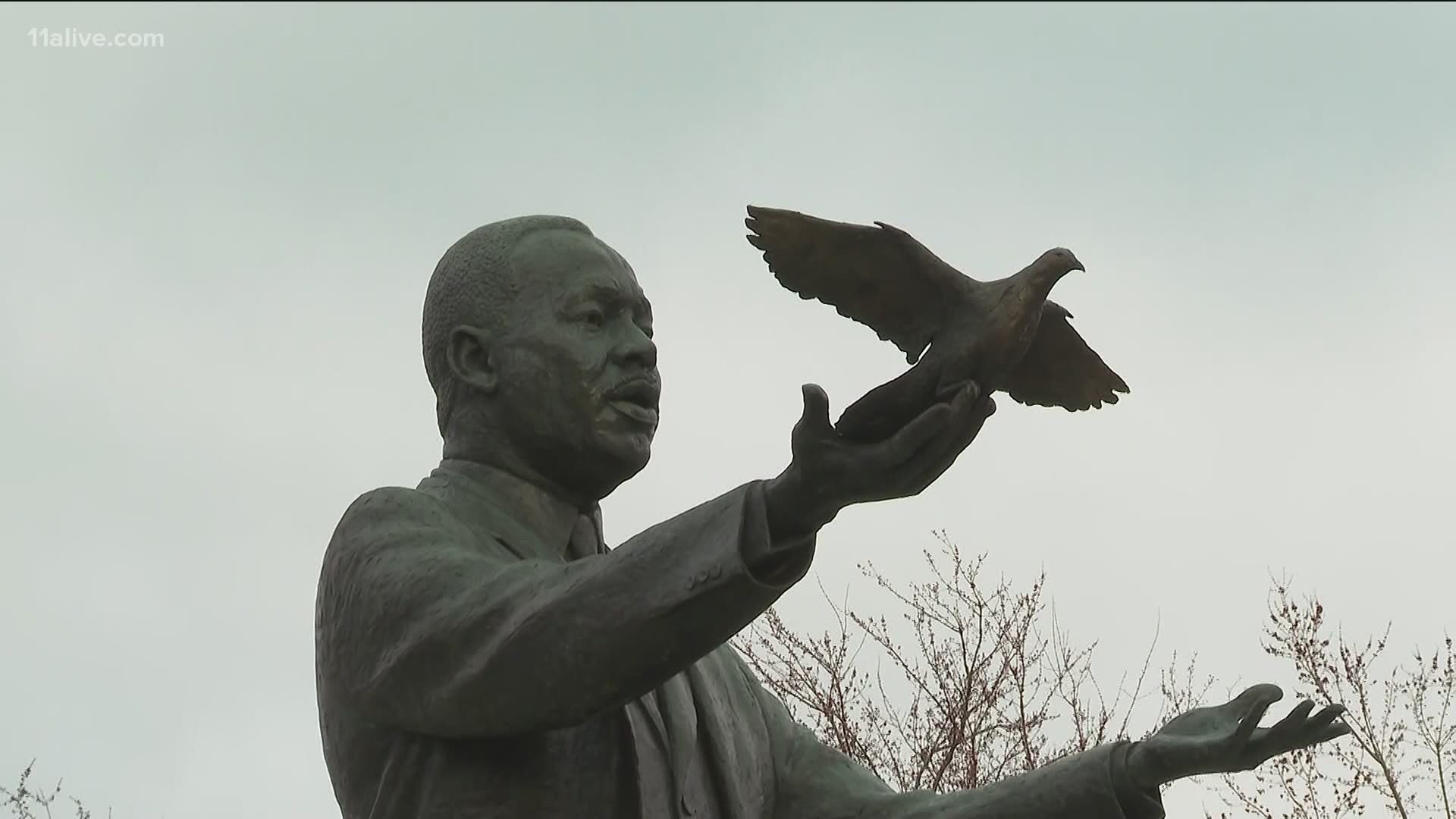

His statue of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., entitled Hope Moving Forward, was commissioned by the city of Atlanta to be one of several works of art placed along Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Drive in the city.

“In terms of my work, it is the most challenging, I think the most significant, most visible work I’ve done," Watson said. “Martin Luther King himself gave his life for the cause, and it’s on his shoulders and others before him and since him that we actually stand.”

The 12-foot bronze statue stands on a 6-foot granite pedestal inscribed with famous quotes made by the Atlanta pastor and civil rights leader.

Watson said it was his largest work to date. The Jamaican-born artist was one of three finalists to develop the concept, and he kept the location across from Mercedes-Benz Stadium in mind to complete the statue. Watson started with a half-life-size model that he got scanned and enlarged. He then applied modeling clay to make a rough prototype in eight months. That portion of the project was sent to the foundry to have a mold made, and Watson proceeded to complete the work.

Hope Moving Forward depicts Dr. King in motion, sending off a fluttering dove, which Watson said embodied King's message of hope, peace, and love.

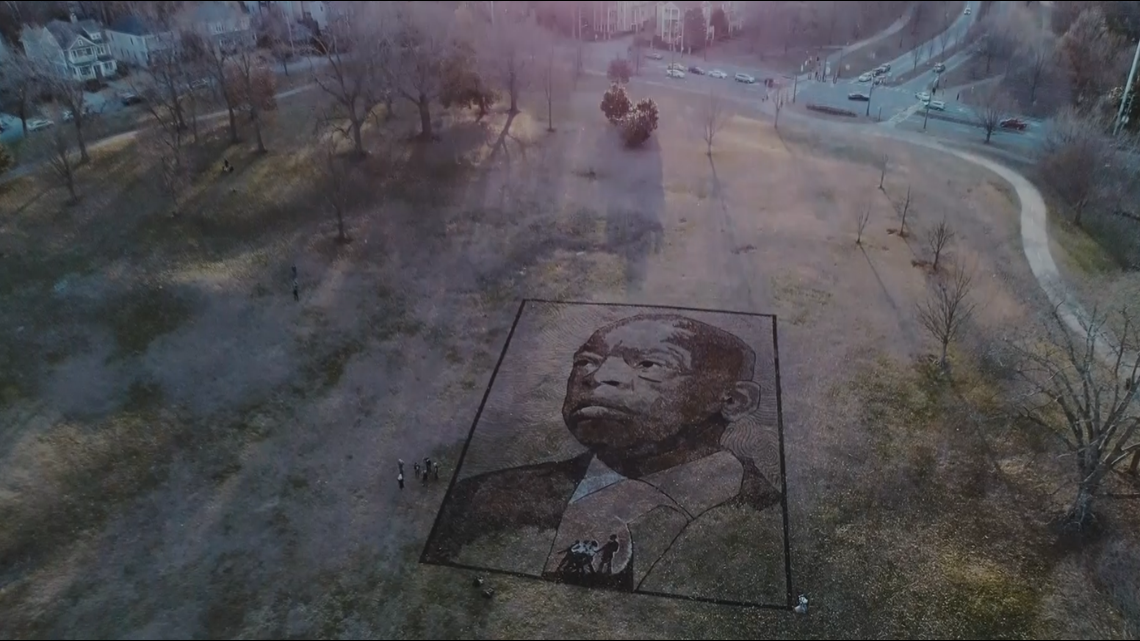

Watson's work is part of an initiative by the city of Atlanta to show off its unique character and publicly display its history. The city has created a Public Art Tour and an app to help people find different works around town. Other works include a Hank Aaron mural by Thomas Turner and a dug-out portrait of John Lewis in Freedom Park, envisioned by Stan Herd.

Camille Russell Love is the executive director of the Mayor's Office of Cultural Affairs. She said the city has poured millions of dollars over four decades into public works of art. The public art program, Love said, took off when Atlanta hosted the Super Bowl in 2019 as a way for visitors to explore social and civil rights issues in the city.

“It isn’t something you have to go to school for. You can actually see it out in your community," Love said. “The exposure to art is as basic a need as food, air, and water, because there’s something that needs to be nourished in the soul that art can do.”

The city has an ordinance that allocates 1.5% of municipal capital construction funds to public art. Atlanta officials get permission from property owners, find and select an artist they believe properly represents the artwork by sending out a proposal, then paying the artist to install work.

“Art makes you empathetic. It provides you with something that will touch your soul and hopefully influence you," Love said. “I think that it’s well worth the investment the city and private industry are putting into making sure art is available to every man in every community in the city of Atlanta.”

Dr. Karcheik Sims-Alvarado, a historian and professor at Morehouse College, said art formed part of the fabric of the Civil Rights Movement in the '60s and '70s.

“Art is somewhat like a looking glass, where we stand before it," Sims-Alvarado said. "We can see through its lens to look back but at the same time, we’re seeing ourselves for who we really are in that moment. Public art looks at who we’re paying homage to, who we desire to be, who do we want to represent us. And Atlanta’s brand is the Civil Rights movement."