COWETA COUNTY, Ga. — The Division of Family and Children Services (DFCS) shoulders the blame when a child is abused or dies. But there is only one authority that actually has the power to remove a child from their parents: a judge.

Yet, when families disagree with a court’s ruling, holding a judge accountable for that decision can seem almost impossible.

That’s why Patrick and Martha Henderson say when a Coweta County juvenile court judge ordered the temporary removal of their children, their first instinct wasn’t to fight - but to run.

“I’m sure there are going to be people who are going to be judgmental and be like, 'You were stupid. You put their lives in danger.' Everyone knows in the back of their minds, if you have children, you would probably do the same thing,” said Martha.

Big picture - the Hendersons admit turning their family into fugitives wasn’t a good idea. But the spotlight on their case has helped expose aspects of our child welfare system that the Georgia Court of Appeals finds troubling.

In its written ruling, Judge Tripp Self writes, “We agree with the parents’ view that this ‘case is about much more than its individual facts. It is about the American legal system, about what our state and country require for every person brought before a court: fairness, respect, and a judicial system that should protect its citizens.’”

But for which citizens should the court focus its protection in a child welfare or dependency case? The parents or the children?

THE CASE

The Hendersons gave The Reveal investigator Rebecca Lindstrom access to their case file, court transcripts and recordings. Lindstrom also spent time talking with their oldest son, who was 11 years old when DFCS became involved with the family.

It was January 2015 when court records say, Martha got mixed up with drugs, her husband Patrick was drinking a few too many beers and the two had a fight about it.

A 911 call to de-escalate the situation later led to a knock on the door by a DFCS case worker.

“It turned out to be the worst phone call ever,” said Patrick.

The Hendersons said for four months DFCS suggested the couple attend counseling to get clean and improve their marriage. When DFCS didn’t feel they were taking those suggestions seriously enough, the to-do list turned into court orders.

The Hendersons argue DFCS failed to give them the resources and information they needed to complete the tasks. and list a series of miscommunications and misunderstandings. Even more frustrating, they say, was that it felt like the goal line to close the case, kept moving.

Instead of support, they felt belittled, such as when DFCS challenged Martha for failing to get a job outside the home to bring in extra income, but then criticized Patrick for missing a counseling appointment because he had to work.

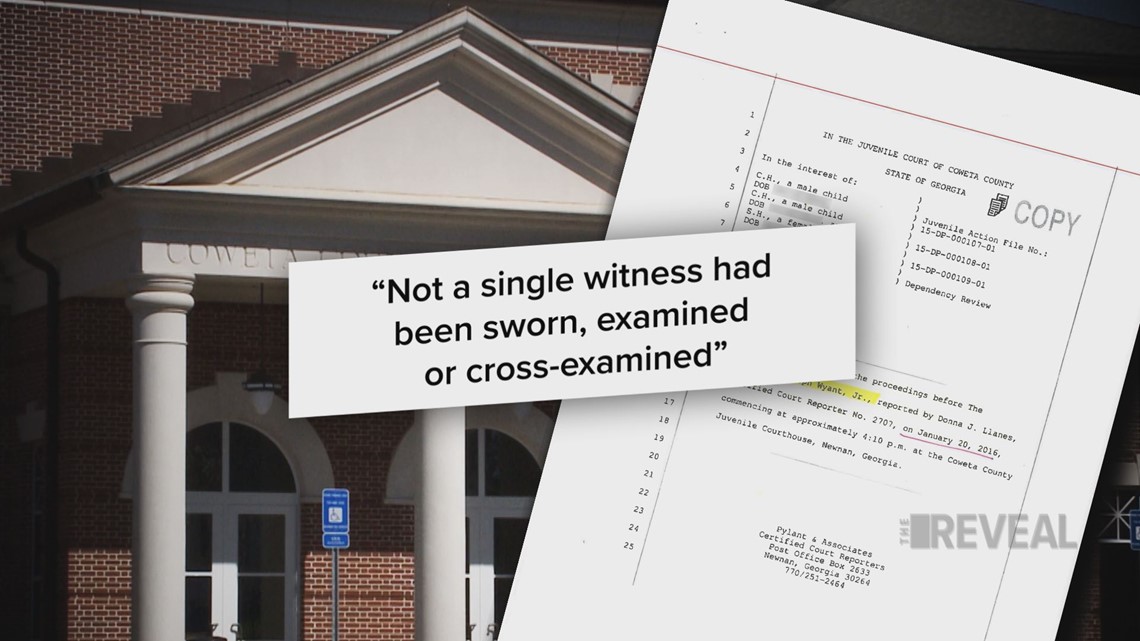

The tension came to a head on Jan. 20, 2016 when Coweta County Juvenile Court Judge Joseph Wyant felt the parents still weren’t following orders on treatment and supervision, and ordered DFCS to take temporary custody of the Henderson's three children.

The problem: The Hendersons didn’t have an attorney the day that decision was made. Their representation filed a motion to withdraw, which due to a holiday weekend, gave them just two working days before the scheduled court hearing.

► OTHER DFCS INVESTIGATIONS | Two children trapped in foster care, as four years later adults still debate how sibling died

The family says they scrambled to find a new attorney but with such short notice, their counsel couldn’t attend the hearing or file the proper paperwork to notify the court of his intent. The family requested a continuance, but it was denied.

The hearing was intended to be a status conference, updating the parents' efforts to get treatment and make sure the kids were receiving proper care.

“Nobody had filed a motion that they thought the kids were in danger,” explained Martha.

According to the court transcript, the Guardian Ad Litem, an attorney that represents the children, told the judge he had concerns the children were missing too much school. But he said he felt the parents were following their case plan and expressed no safety concerns.

DFCS did not feel the same.

When asked by Judge Wyant if the children were in imminent danger, DFCS said, “yes."

Without swearing in any witnesses, presenting any evidence or giving the parents a chance to formally rebut the statements made, the judge made the decision to put the children in the state’s custody.

“You are trying to defend yourself, you have papers in front of you, you’re like, 'It’s right here. No, that’s wrong, you’re wrong,'” recounts Martha. “I’m looking over at the attorney who apparently withdrew, and she has her arms crossed just looking at us.”

The judge did schedule a hearing the following week to decide what should happen next, but the Henderson's weren’t sticking around. They loaded the children in the car, leaving everything they owned behind, and drove to Louisiana.

It didn’t work. In the eyes of the law, the Hendersons had interfered with state custody, essentially kidnapping their own children. There was an Amber Alert, newspaper headlines and arrest warrants.

Two weeks later, U.S. Marshals found them asleep in a friend’s trailer.

“When they beat down the door, there were literally lasers on every one of our heads. My 18-month-old daughter had a laser on her head,” said Martha.

SOMEONE MADE A MISTAKE. BUT WHO?

It was the Henderson's criminal attorney, a public defender in Coweta County, that first expressed concerns over how the parents lost custody of their children.

As the criminal case worked its way through the superior court system, the family also hired attorney Corinne Mull to file an appeal in juvenile court, trying to get the order removing their children ruled null and void. When that didn’t work, they appealed to the state court.

There, the judges seemed bewildered that a juvenile court judge could make such a ruling while the parents did not have legal representation.

In his written ruling, declaring the order to remove the children null and void, Judge Self wrote, “Constitutional rights are commandments, not suggestions.”

Chief Judge Stephen Dillard went on to call the state’s justification for removing the children, “nonsense on stilts,” citing case law declaring parenting to be “a fiercely guarded right … that should be infringed upon only under the most compelling circumstances.”

With the Georgia Appeals Court ruling, the Henderson's were able to file the proper motions to have their criminal convictions removed.

Still, the Georgia Attorney General's office stood by the original decision made in the Coweta County courtroom, taking the case a step further to the Georgia Supreme Court.

According to an open records request, the Department of Law spent 450 hours defending DFCS and the judge’s actions on appeal, not even counting the hours spent by Linda Taylor, a private attorney hired by DFCS.

Attorney and Judge Pro Tem Ashley Willcott says she understands why the state fought so hard to explain its case. Willcott once lead the Office of the Child Advocate and says most of the time when kids come into state custody, they need to be there. She defends the ability of judges to move fast when a child is in danger.

“Children are abused and neglected in circumstances and situations that are not rational. That are not calm. You may have for instance a meth home or a lab explosion and the children have to be removed because there’s no one else, no relative available that can come and get the children. In those circumstances, it’s immediate,” explained Willcott.

But the Hendersons argue this was not that situation.

THE IMPACT

Their oldest son, who we are not identifying to protect his privacy, says he never felt abused or neglected by his parents. He sees DFCS and the court as intruders into his family’s life. To be fair, it's a common and natural feeling for children who come into contact with the system.

“I’m with my family back now. Thank the Lord for that. But I think that sometimes, what if it didn’t go this way?” asks their son, taking a break from a family game of football.

After eight months in foster care, Martha finished therapy and Judge Wyant returned the children home. They were long, painful months.

“To lay there night after night and cry and cry and cry because something that’s a part of you, that you wake up and breathe to, is not there,” explained Martha.

Their youngest child, a bouncy little girl with a love for rainbow ponies, for months expressed fear every time her parents walked out the door.

“I would run to get something from the store and she would say, ‘Daddy, you leave. You always come back?’ I say, ‘Yes baby, I always come back,’” explained Patrick.

During the state’s involvement in the family’s life, their oldest admits his grades were poor. There was too much insecurity at home and, while in foster care, he says it was hard to focus.

“You get all emotional in class and no one in class knows why you’re getting so emotional. Why did you start crying in class?” he recalled.

Judge Wyant declined to comment about the case or the appeals court ruling. The family filed a complaint with the Judicial Qualifications Commission, but no disciplinary action was taken. An open records request showed none of the caseworkers faced disciplinary action either.

An attorney for DFCS stated in oral arguments that the case was, “not so much about what the juvenile court did, but the appellant’s own actions.”

There are those that argue had the parents been more proactive about their treatment they wouldn’t have lost custody. Or if they had stayed in Georgia, they would have been given custody of their children back sooner.

But neither argument changes the power our child welfare system has to remove children from their home if a judge believes they are not being cared for properly. It’s not just physical or emotional abuse. A judge can remove a child because they’re missing too much school or the parents aren’t providing proper supervision.

“The system has to be held accountable. The judges have to be held accountable,” said Willcott. “That’s why the appellate system is effective and works in my opinion. Having said that, we have 159 counties in the state of Georgia and often in all courts, 159 different ways of doing things. They’re all adhering to the law, but may interpret it different ways. And that’s where I think there can be a frustration around the child welfare system.”

Judges can only make decisions based off the information provided. They count on that information being accurate, or challenged by the attorneys involved when it is not. The Hendersons say that's why having legal representation is so important and are grateful for the ruling affirming such.

But the appellate system takes time.

To this day, the Henderson's oldest son, the very person the child welfare system is supposed to help, does not see DFCS or the court as a system designed to lift families up, but rather tear them down. He says efforts to protect them physically, or even educationally, ignored their needs emotionally.

“I wanted people to know what we’ve been through,” he said.

The Reveal is an investigative show exposing inequality, injustice, and ineptitude created by people in power throughout Georgia and across the country. It airs Sunday nights at 6 on 11Alive.