ATLANTA — Infants, toddlers, children: they're starved, beaten and sometimes thrown away like garbage. Their caregivers end up on trial for their murder.

Trebor Randle, special agent in charge for the GBI Child Fatality Unit, investigates between 100 and 150 cases of neglect-related abuse death a year.

She said the saddest part is she often sees many missed opportunities to save a child’s life.

“These cases are happening on a regular basis,” Randle said. “An 18-month-old that had bruises from his head to his toe - and then it’s a situation where the child was left in someone else’s care.”

She’s familiar with all the cases 11Alive has covered in the past year.

From Emani Moss, a 10-year-old starved to death by her stepmother, to Reygan Moon, a two-year-old weighing 14 pounds when she died. Her mother is accused of murder.

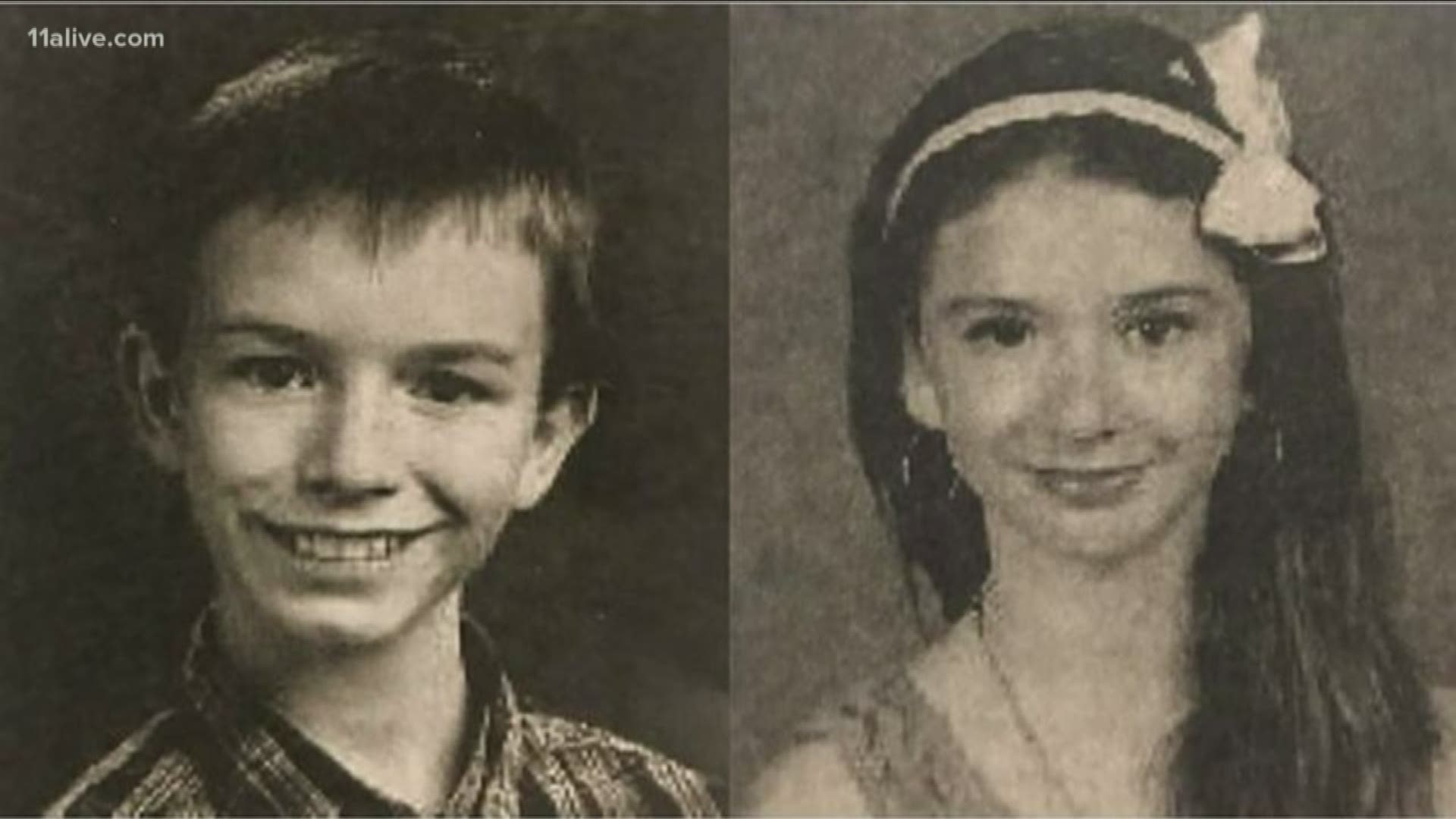

Recent horrifying tales of abuse include Mary and Elwyn Crocker, Jr., two young teens found buried in the backyard of their families’ home. Investigators say Elwyn was starved and locked in a cage like a dog. Her father and four others are charged in connection with the deaths.

More recently, the trial began against Jennifer and Joseph Rosenbaum, two foster parents accused of killing 2-year-old Laila Daniels.

“The reality is there are many more cases,” said Randle.

In case after case, Randle sees one glaring similarity.

“You see all of the red flags where someone could have intervened,” she said.

Randle explained caregivers can be addicted to drugs or alcohol, suffer from mental illness or live in poor socioeconomic conditions. The situations can differ, but she firmly declared that, in almost all cases, something could have been done differently to save a child’s life.

“Oftentimes, they will say, 'That’s not my problem,' until they see the medical examiner’s van pull up to that residence and they know something has happened,” she said.

Whether it’s strange and unexplained bruises on a child or a case of starvation, Randle said there are, more often than not, obvious signs of abuse.

“That is not a process that happens overnight,” the agent said. “If you see those kids, they’re not making eye contact. They’re unkempt, something has happened.”

In the cases of Moon and Moss, the family did try to get involved by contacting the Georgia Division of Family and Child Services. DFCS admitted in the past they “dropped the ball” in some cases. However, Randle added that shouldn't sway more people from trying to get involved as soon as possible.

“They have seen something that doesn’t sit right with them. It starts there," she said. "If you see something that’s off, you have to say something. Pick up the phone - call 911 if you have a concern about a child being abused.”

Randle works closely with DFCS, schools and other law enforcement agencies to close any gaps when someone makes a complaint about abuse of a child. She added anyone can leave an anonymous tip with DFCS or law enforcement if they suspect abuse.

For more information, Randle recommended accessing information for on ChildHelp.org.

MORE NEWS