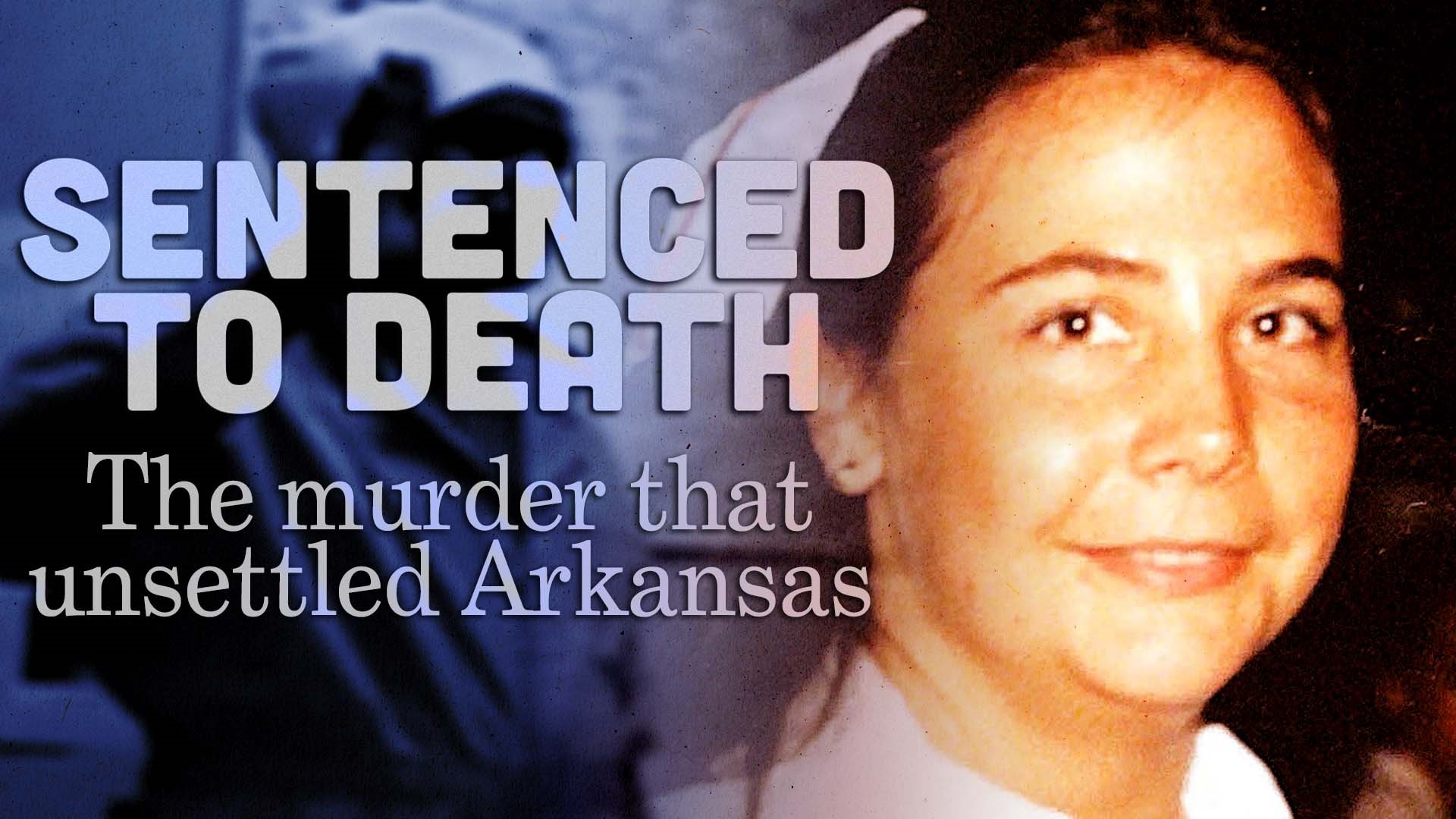

In 1983, a nurse was murdered in Arkansas. A second look at the investigation

Forty years ago, Barry Lee Fairchild was arrested for the murder of Marjorie 'Greta' Mason. This documentary looks at the investigation and the questions that remain

For twelve long years, Arkansas heard about the murder of an Air Force nurse and the suspect's pleas and appeals to prove he was not the killer until his last breath.

Now four decades later, we talked to those who covered it, the victim's family, and experts about the murder that unsettled Arkansas.

Some of the language used in this article and the accompanying documentary may be offensive or outdated terminology.

The Car Chase

It had just gotten dark on the night of Feb. 26, 1983, when a car’s headlights struck across Arkansas State Trooper Danny Ferguson’s windshield.

He clocked the Toyota going 62 miles an hour, nearly 20 miles faster than the speed limit signs along the highway he’d been idling on just within the city limits of North Little Rock. Ferguson turned on his blue lights and threw his patrol car in drive.

The chase would only last around five minutes, but it began the unraveling of a tragedy that’d haunt a generation and then be buried.

By the time Ferguson caught up to the silver Toyota, it had skidded to a stop in an open field near waist-high weeds. He knew the suspect behind the wheel was in the wind when he saw the driver’s side door hanging open. A passenger, however, responded to his demands and crawled out of the car, squatting.

That’s when Ferguson noticed the gun in the man’s belt and struggled back to his vehicle to call for backup.

Because the chase was so intense—speeds got up to 87 and a handful of cars were run off the road—he was having trouble finding his microphone that had fallen under the seat to alert for backup.

Once he returned his attention to the car bearing Florida plates, the man was gone. “Evidently, the suspect crawled through the grass and made his escape into the darkness,” Ferguson said in the closing sentences of an incident report.

Police found out the car had been stolen from Marjorie Mason, a 22-year-old woman who moved from her home state of Florida 10 days prior to start her new life in North Little Rock as an Air Force nurse.

The Victim

Marjorie Mason, or Greta to all who knew her, had been an eager, bright-eyed 22-year-old when she moved to Arkansas in February 1983. She’d been transferred to Little Rock Air Force Base to begin her career as a nurse, a dream she had since she was a kid.

Greta grew up in a sleepy beach town where palm trees lined the curb. Everyone in her life had respect for the kind leadership that seemed to come naturally to her as the oldest sister of four siblings.

“We lived in a house in the cove area of Panama City for a long time. It was on the water. We water skied, we sailed, fished, swam, all the watersports we could do.”

Forty years later, one of her brothers reminisces about their idyllic childhood and the neighborhood they grew up in called the Cove. Eric, who is now in his early fifties, sits in a suit and tie with binders full of old photos in pristine condition stacked on the table in front of him.

While carefully turning the pages, there was a hollow feeling that went along with every photograph Greta was in. She was laughing, others were looking at her, or she was smiling and in turn, others were too.

There was a confident grace and magnetic influence Greta had, something that a stranger a lifetime away could somehow understand.

And to Eric, he seemed to carry the weight of her memory thoughtfully and left no stone unturned.

He sits in a large conference room at the police station he retired from years ago, remembering his sister and their lives growing up. He laughs at memories he hadn’t thought of in a while and names of friends they grew up with, many of which he hasn’t heard from since her funeral.

“We were all part of the same church… and we all became extremely good friends.” He rattled off their names as if they were imprinted there, small details along with each.

“The people were like family to us, brothers and sisters. And Greta pretty much was the one that everybody kind of centered around.”

And it was her tragic death, he said, that splintered apart the kids from the Cove. Even though many had since moved away and gone their separate ways, they all couldn’t reconcile with each other because the person they looked to had vanished.

Where Eric had light in his eyes speaking of Greta, their brother Billy had fire.

“Losing her is a sacrifice. But to forget about her and let her die is a much bigger crime than having to put up with the pain of talking about the situation.” Billy spoke as if he’s been close his whole life to finding an answer, but never able to grasp it.

When it came to things she cared about like the church, school work, or the ROTC program, Billy said Greta made large successes look easy. She had been chosen out of hundreds of applicants to become a second lieutenant in the Air Force right after graduation.

“But she didn't even have time to enjoy her life. Because once she got into Little Rock, within two weeks, she was kidnapped and killed.”

The Murder

Ten days after moving to North Little Rock, Greta’s apartment was still empty. According to court testimony, when she finished her shift at the base and went to a furniture store on Feb. 26, 1983, her fate was sealed.

Both furniture stores on East Washington Street were closed—it was 4:30, and sometimes the mom-and-pop stores would decide to close early on Saturdays. When she realized the Auction House of Bargains’ doors were locked, Greta walk back to her Toyota Tercel while two men watched.

She was still wearing her white nurse’s uniform when they caught up to her while she opened the door and forced themselves on either side of the car. She was shoved in the middle with a gun pointed at her.

It was about two hours after her abduction that North Little Rock officers responded to what was left of the car chase that involved Greta’s Toyota Tercel. A blue and white hat with the words “CAT diesel power” was found in the driveway of a nearby house. Police strongly believed the hat had fallen from one of the suspects.

The hat was identified by NLR police officer Wayne Chaney as belonging to a man he knew well, both as someone who had run-ins with police and who had helped him in drug busts named Barry Lee Fairchild.

The two suspects, only identified by Trooper Ferguson as two Black men, were not found that night.

The next morning, an Arkansas State Police investigator received a report of a farmer in Scott finding important-looking documents belonging to Greta littered like trash in one of his pastures.

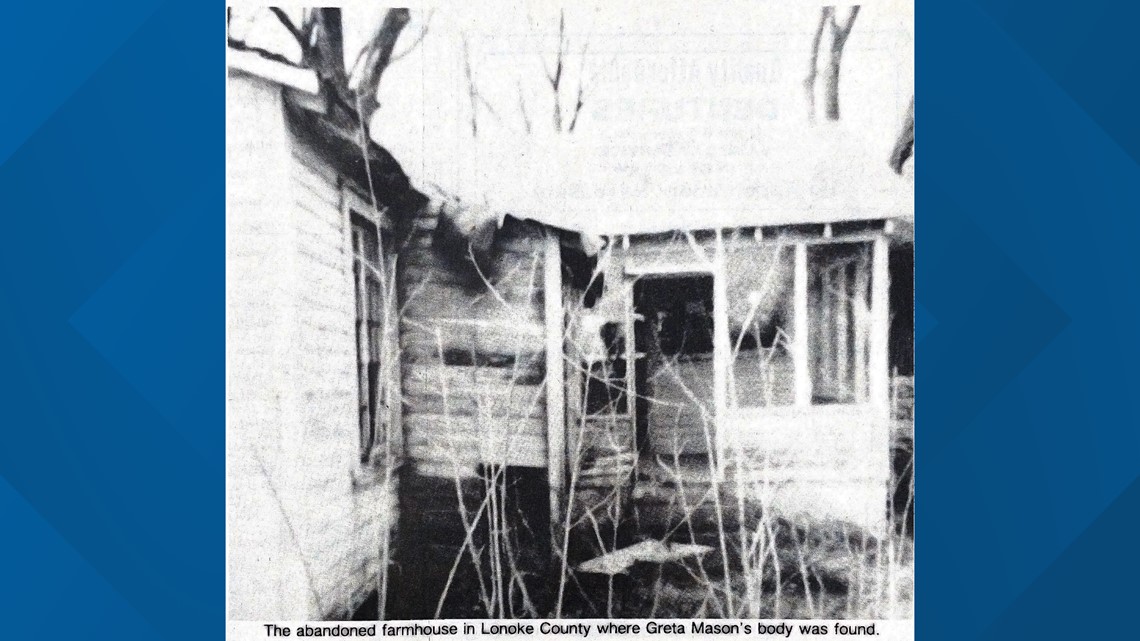

Soon after the trooper arrived, he found a woman’s body around the back of an abandoned farmhouse on the property.

The crime scene was first believed to be in Pulaski County although the farmhouse stood about 500 yards from the county line into Lonoke County— which in 1983, was home mostly to farmers, families under the poverty line, or both.

The sheriff’s department in Pulaski County led by Tommy Robinson was larger and covered a wider population, so they lead Greta’s murder investigation.

According to Greta’s autopsy, Pulaski County Lt. Tom Waggoner, one of Robinson’s top deputies, was the one to identify her body. He also found pieces of her clothing inside the farmhouse days after multiple agencies had combed the scene.

Greta’s autopsy showed signs that she had been raped and shot twice in the head. The medical examiner found the two bullets still lodged in her skull and labeled them “MM” (for Greta’s government name Marjorie Mason). Those bullets would later turn up missing from evidence.

Once her cause of death was ruled a homicide, Robinson led his deputies—with Major Larry Dill as the lead investigator, on a hunt for the two Black men who were responsible for Greta’s kidnapping, rape, and murder.

The Arrest

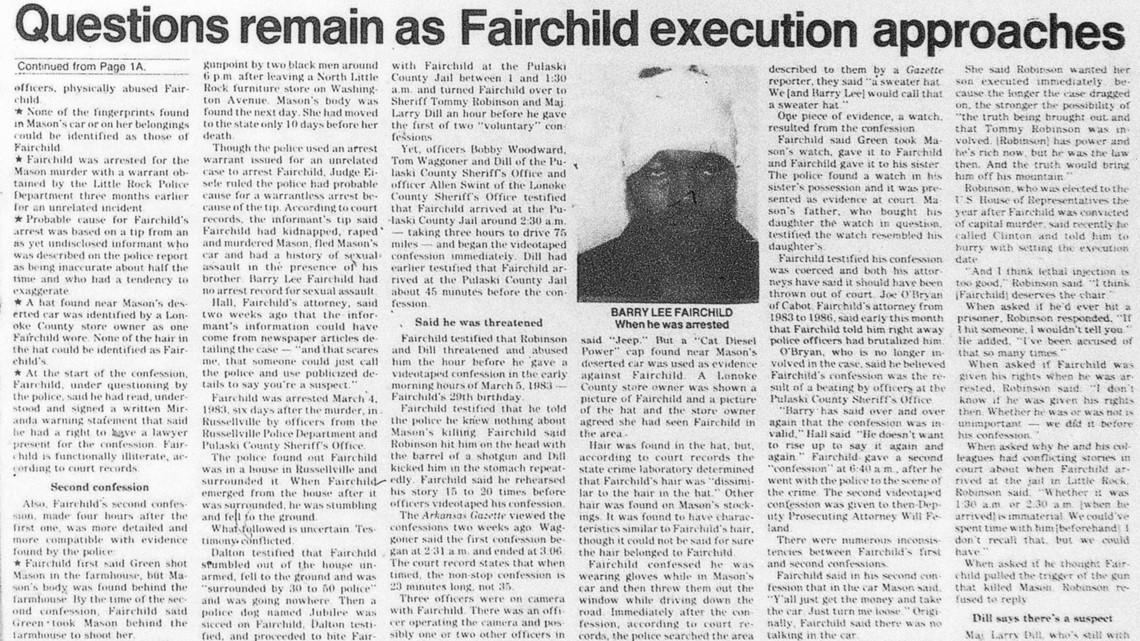

Five days after the murder, deputies had a tip that a suspect, 27-year-old Barry Lee Fairchild, had boarded a bus in Conway en route to California. When deputies tried to stop the bus in Russellville, he avoided arrest by walking away without authorities recognizing him.

Although Russellville sat firmly in Pope County, a horde of Pulaski County deputies descended on the city that was over an hour north of Little Rock in hopes of catching Barry, the man who they wouldn’t let get away for a third time.

After nearly two days of authorities searching for the 27-year-old after the bus incident and announcing a manhunt for Barry over the radio, police got the call they’d been waiting for.

A Russellville man was in his family’s home when he noticed a Black man had knocked on the front door asking if they could call him a taxi because his car broke down. The man matched the description he’d heard over the radio and called 911.

Barry Lee Fairchild’s arrest details are best described as a disorganized frenzy but well-intentioned. At worst, if some first-hand witnesses are to be believed, the events reveal an investigation shrouded with errors.

Some officers claimed a handful of police were present, while one, in particular, claimed there were 30 to 50 armed officers outside of the home Barry had allegedly just entered.

Russellville Police Officer Ronald Stobaugh, who was the first to arrive at the scene, noticed a Black man through the window in the front door and pushed it open, yelling for him to raise his hands. According to Stobaugh’s arrest report, he grabbed Barry’s shirt collar and pulled him out the door. As the two came through the front door, two more officers jumped in and began struggling to subdue Barry, whose clothes were damp from the rain after meandering the outskirts of Russellville for the past 36 hours.

As the officers and Stobaugh had their hands on Barry “struggled to free himself” and they all fell to the ground.

“We were trying to place the handcuffs on him when Jubilee appeared,” Stobaugh said.

Pulaski County Cpl. Sam Chamberlain was the handler of Jubilee, a German Shepard K9 officer with the sheriff’s office. The facts in Chamberlain’s arrest report were noticeably different from Stobaugh’s.

Chamberlain said: “Major Stobaugh grabbed at the suspect and knocked him off balance causing him to fall to the ground. The subject fell face down on the ground in the front yard near the street and Jubilee grabbed him by his clothing and held him until officers were able to subdue him and place handcuffs on him.”

“While the subject was on the ground,” Stobaugh said in his contradicting report, “Jubilee grabbed him on the back of the head.”

Stobaugh’s report paints the scene of several officers at the scene of Barry’s arrest, saying that about 10-15 deputies arrived “from the time we came off the porch until the suspect was cuffed.”

Stobaugh said Barry was then placed in Russellville officer Larry Dalton’s patrol car along with an unnamed Pulaski County deputy to the hospital, where he received six stitches for the dog bite on his head.

Upon his release from the hospital, Barry was charged with resisting arrest and fleeing by Russellville police, given a citation, then handed over to Pulaski County deputies.

Dalton testified years later that he thought Jubilee’s release was unnecessary. He said there were dozens of armed police surrounding the front yard and street by the time Stobaugh and two deputies had their hands on Barry.

Dalton’s testimony was deemed unreliable by a judge due to the former officer-turned-private-investigator’s past looking into fellow policemen while working as a private investigator.

Barry himself would claim in his videotaped confession, hours after his arrest with a bandage surrounding his head, that he was in custody when Jubilee bit him.

To fully understand what led to Fairchild's arrest that night in Russellville, we have to go back two months before Greta's murder during the week of Christmas in 1982 when a Little Rock officer was shot at while responding to a store robbery.

The two suspects in both the robbery and shooting were Black men. When he confronted the suspects and he was shot at, the officer couldn’t say whether one or both men had guns or even which man had been the one to shoot in his direction.

The officer was able to identify Harold Green, a man known to police for petty crimes, in a photo lineup but couldn’t identify the other Black man. A confidential police informant gave Barry’s name as the other suspect. This wasn't shocking to the police considering the two had run in the same circles for years.

The informant was described in police documents as being "generally reliable," "correct about 50% of the time," and "known to embellish stories." Even so, it was based on his statement a warrant was signed to arrest Barry for the attempted murder of an officer.

This was the warrant that Pulaski County deputies were arresting Barry with on March 4, widely assumed due to their lack of physical evidence in the murder of Greta Mason. The warrant for the attempted murder of the Little Rock officer, not Greta’s murder, is what Barry later would say he was trying to avoid by skipping town.

His mother Merdine Fairchild said NLRPD Officer Wayne Chaney came to her home looking for Barry, saying the sheriff’s department would shoot him if they had the chance since he was considered armed and dangerous. She was worried for his life and gave him $200 of her $212 paycheck to board a bus to California.

But Pulaski County deputies’ determination to nab Barry as their guy wasn’t just fueled by nothing.

He was an early suspect because of the blue CAT diesel power hat found by Chaney who said he’d seen Barry wear a similar one. On top of that, the same informant in the officer robbery/shooting gave Barry’s name again in Greta’s murder, along with his younger brother Robert.

Now that Barry was in custody, Pulaski County deputies needed a confession to officially charge him with capital murder.

There were two videotaped confessions four hours apart in the early morning hours after the arrest.

The first was recorded at 2:30 a.m. and the second started at 6:30 a.m. after Barry was taken on a “tour” of the crime scene with Sheriff Robinson, Dill, and other deputies.

Details and the timeline of the crime told by Barry in his first confession are wildly inconsistent with what investigators knew to be true at the time.

Lt. Waggoner is on Barry’s right with Officer Chaney and Lonoke County deputy Allen Swint on his left. Barry’s head is completely wrapped by a bandage covering the wound that was stitched by Russellville nurses a few hours prior.

He said his accomplice was Harold Green, who wanted to kidnap Greta after they saw her outside the furniture store that evening.

Barry couldn’t explain well where the farmhouse they brought her to was located and wasn’t sure what kind of gun Green had. But it didn’t seem like Barry was being intentionally difficult to thwart the investigation, he was showing an almost childlike need for approval, which was followed by what looked like disappointment when he’d gotten a question wrong.

He said he drove to Scott where Green raped her, along with a simple “mhm” when asked if he did, too. However, Barry raping Greta is then left out based on his recollection of events. He said when they arrived at the farmhouse, he stayed in the car, rifling through her purse when he heard two gunshots and ran into the house to find Green had shot Greta twice in the head.

Despite the direct confession, questioning by Waggoner appeared motive-driven in an effort to get specific answers. Three times he asks what color hat Green was wearing, hoping to get Barry to describe the blue hat found by police. Each time, Barry said it was a green hat and that JEEP was on it instead of CAT diesel power, even after being shown a polaroid of the hat and answering “yes” when asked if he knew how to read in the opening of the taped interview-turned-confession.

Waggoner also repeated a line of questioning about whether Barry heard Greta say anything during her abduction or rape. Twice, Barry said no.

Moments later Waggoner tried again. “Was the lady saying anything to you?”

Then, Barry paused and stuttered when answering. “When he first got out of the car with her, she told him not to do that, you know…”

As if that still wasn’t the answer they’d all been looking for, Officer Chaney spoke up.

“When y’all was going out there, what was she saying?”

“Nothing.”

“She wasn’t saying nothing?”

“She wasn’t saying nothing.”

Chaney asked the question for the sixth time: “She didn’t say a thing?”

Barry shakes his head. “Nuh-uh. She didn’t say nothing.”

Waggoner looked sideways and made eye contact with someone behind the camera. Even in a poorly lit, unfocused shot in a 1983 videotape, a brimming irritation can be observed on the lieutenant’s face.

Soon Barry and the other officers follow his glance off-camera. Waggoner backtracked. “And you were sitting in the car going through her wallet, her purse?”

At one point, when Barry keeps getting his directions mixed up, Swint lights a cigarette and hands it to him. Waggoner told him to relax, that it’ll be alright.

In the second video, Barry is now wearing a bright orange jumpsuit after he’d been wearing a dark gray one in the first tape, the same bandage was wrapped around his skull.

After visiting the abandoned farmhouse with authorities in what was later described as “the tour,” Barry now sat next to Pulaski County prosecuting attorney Dale Adams. It was 6:30 a.m. on March 5, his birthday.

His confession to Adams is much more concise due to much more direct questioning. Barry now definitively said the gun was a .22 caliber. Adams doesn’t ask Barry to go into detail in the same areas that seemed to trip him up in the first confession. A stutter, however, is much more noticeable as he explained his role in the crime.

Adams does ask Barry whether he heard Greta say anything. Now, more flare is added to Barry’s response. Greta now had been crying “please don’t hurt me...I’ll do anything y’all want.”

Instead of having Barry describe the hat, Adams showed Barry the same polaroid of the hat and asked him whose it is. “That’s the one he was wearing,” he responded.

Again, he described both he and Green raped Greta, despite initially saying he stayed in her car and only got out after hearing the gunshots.

In neither interrogation is Barry asked whether he pulled the trigger nor if he knew Green would kill Greta.

The attempted murder charge against the Little Rock officer was dropped soon after his arrest and Barry was now charged with kidnapping, rape, and capital murder.

Not long after these confessions, police served Harold Green with a warrant for his arrest. The investigators quickly found out he was in a Colorado jail the night of the murder, poking a hole in Barry's already shaky confessions.

The charges against Green were dropped, but Barry's remained.

And as Furonda Brasfield, a criminal defense lawyer in Arkansas pointed out, under Arkansas law you can be charged with capital murder as an accomplice and still be sentenced to death.

“Felony murder in Arkansas is a system by which if you are in the commission of a felony, then anyone that's killed in the commission of that felony, you're responsible for that even if you didn’t pull the trigger,” Brasfield explained.

In Fairchild’s case, the death sentence was on the table, and the jury took it.

Physical evidence found at the scene like DNA, hair, and fingerprints—none could be 100% linked to Barry.

Immediately following his arrest, Barry recanted both confessions and accused Pulaski County deputies, specifically Robinson and Dill, of coercing the story out of him.

He told his lawyer he was beaten and coached to remember facts surrounding the murder. Barry used Green’s name because they’d been linked before and it was who deputies “wanted” him to say.

Even so, in August 1983, Barry Lee Fairchild was sentenced to die by lethal injection.

Barry's IQ

The overseer of all of Barry’s post-trial decisions, District Judge G. Thomas Eisele, was known as a moderate judge who was highly respected in the Arkansas court system. Over the years, he would hear more and more on Barry's intelligence.

A sheriff’s deputy who knew Barry since he was 10 years old after he was caught stealing bicycles described him as “slow, uneducated, and scared of authority.”

At 16, Barry was arrested for stealing a horse. In his release paperwork, it's noted that he struggled in school, attended special education classes, and had a speech impediment. At one point, it said Barry wanted to go back and finish school so he could "talk better" and help out his mother with the bills.

Barry dropped out of ninth grade following his release from jail, never learning how to read or write.

“What I noticed is that Barry Lee Fairchild had a very simple outlook on life. And so clearly what the attorneys later argued was mental retardation status for sure,” Phoebe Howard, a former Arkansas Gazette reporter said.

In 1989, Howard questioned the sheriff department’s investigation and wrote about the inconsistencies. She faced critics, both within her own newsroom and outside of it, receiving death threats related to her reporting on the Barry Fairchild investigation. After reading her stories in the newspaper, she became the only journalist he allowed to visit him on death row.

Barry took IQ tests throughout his life, none were above 87, a designation of low-average score intelligence.

His earliest IQ test was taken in 1966 when he got a 63 while in primary school, landing him in the bottom 2% of the population in terms of intelligence long before he was on trial for murder.

Throughout his appeals, his low IQ was a pervasive theme whether it was forthright or a supporting factor.

Over and over, for over a decade, Barry’s legal team would mostly center their arguments on the idea that Pulaski County deputies manipulated him that night to get a confession—using physical harm to seal the deal.

In a post-trial argument, Barry’s lawyers argued he had a low IQ and was what experts at the time called “mentally retarded.”

After his arrest and time in prison, he took several IQ tests ranging from 60 to 87.

Dr. Ben Silber, a practicing forensic psychologist who routinely gives psychological evaluations to inmates, said the 87 score was from a test that isn’t the most reliable when understanding someone’s overall IQ. The Beta test, Silber said, is a nonverbal test made to be given in group settings.

“[Barry] was primarily illiterate, couldn't really read, couldn't really write. There's a lot of records that note that he had difficulty with verbal comprehension to communication. So there are some difficulties with speech. The interesting thing is that the Beta test does not have tests of verbal intelligence. I think most would argue that that is extremely important,” Dr. Silber said.

He cited one of Eisele's points made in an opinion that Eisele ultimately believed adaptive functioning is more important than an IQ score.

“The funny thing is, at least in the records I reviewed, nobody did an assessment of adaptive functioning. So sure, it's more important. But who did it?” He asked. “The psychologist who tested [Barry] specifically says, ‘I didn't assess for adaptive functioning.’ There's a very specific quote where they say, ‘No, I didn't do that.’”

Silber made these observations with an equally firm obligation to point out how new the research in forensic psychological evaluations was in the late 1980s and early 90s. It was the Wild West of understanding a defendant’s mental capacity, let alone what it was when confessing to a crime.

When Barry agreed to his Miranda Rights the night he confessed to kidnapping and rape, his appeal lawyers claimed he didn’t fully understand that his words could actually be held against him or that he would be held responsible for Greta’s death.

Five of the six experts who testified in the hearing found Fairchild to be intellectually disabled. Eisele’s ruling to the contrary was based on the testimony of the outlying expert who disputed Fairchild’s competency.

Eisele ruled that “no reasonable argument could be made” that Barry’s IQ “whether 63 or 87 or some other number” would make his confessions to murder unreliable or inaccurate.

Howard is still a journalist in Detroit where she’s originally from. She was frank in her answer when asked if she could consider her time sitting across from him on death row and whether she agreed with claims of mental disability.

“I think that was a legal strategy,” she said. “But he was somebody who absolutely had a very simple take on life and how he engaged. How you would define that legally, I don't know. But he was absolutely just his whole approach to everything was very, very simple.”

Abuse allegations

By 1983, Sheriff Robinson wasn’t a stranger to scandal. Just two years prior, the county jail was overcrowded and Robinson blamed the issue on convicts being held there awaiting state prison time. In a protest, he drove a group of jailers to Pine Bluff, handcuffing them to the fence outside a prison facility.

According to news reports at the time, all but one of the men had been charged with a felony offense and all but one were Black.

According to the Central Arkansas Library Encyclopedia, Robinson told reporters at the scene he’d deputize them and issue them a weapon to fight against state police who arrived to stop his operation. State police never arrived, and eventually, the jailers were taken somewhere else.

Barry testified that Tommy Robinson, who had been elected to the U.S. Congress by the time appeals began, had threatened to kill him and hit him with the barrel of a shotgun. He also said Larry Dill kicked him in the stomach before he confessed.

He also said they “wrote down things for me to say” and rehearsed the statements “six or eight times.”

Dill denied the allegations. He said Barry spoke “freely” and that absolutely no physical abuse occurred. “I don't think Mr. Fairchild could have memorized a script if he was given one,” he said, adding, “I’m aware that nobody did that—wrote out statements for Fairchild to say.”

However, just before Barry’s scheduled execution in September 1990, former Pulaski County deputy Frank Gibson told the FBI damning evidence that would halt the execution.

The FBI opened an investigation of police brutality within the sheriff’s office led by Tommy Robinson from 1981 to 1984, including the Greta Mason investigation. Gibson, who later left the department, said that physical abuse occurred during the Mason investigation and that he was a part of it.

Gibson said that he, Robinson, Dill, and other deputies severely beat Barry’s younger brother Robert to confess to killing Greta two days before Barry’s arrest.

Dill tied a wet towel around Robert's neck and choked him until he passed out, causing him to defecate on himself, according to Gibson. When he returned home after denying any involvement, Robert’s mother Merdine testified that he walked through the front door in a jail jumpsuit carrying his soiled clothes in a grocery bag.

Gibson also testified that it was an open secret in the sheriff’s office that Barry was beaten into confessing.

After the information came out in the press, Barry’s legal team was in contact with 12 other Black men, not including the Fairchild brothers, who came forward with stories of abuse by deputies investigating Greta’s murder.

Once the district court ordered access to the Pulaski County sheriff's files in 1990, it became clear that the 1983 trial testimony from Robinson and other deputies had bent the truth when they said Barry was the only prime suspect all along. He was one in a group of fourteen.

The men, who as a group were wholly unconnected despite living in the same area and being Black, had differing stories of abuse with pieces of information that mirrored each other.

One of the men who came forward, Robert Johnson, said he was arrested on the mistaken belief that he was his brother, Michael Johnson. When he went to get his ID to prove it was him, deputies took him into custody anyway.

He testified that he was kicked in the groin by Waggoner when he didn’t have information on Greta’s murder.

His brother Michael was eventually brought in for questioning and said Dill put an already written out statement confessing to the murder in front of him to sign.

When Michael asked for a lawyer, he said Dill pulled out a gun, put it in his mouth, cocked the gun, and pulled the trigger. That’s when he knew the chamber had been empty, according to his testimony.

Michael’s mother Mary Johnson testified that when Michael came home after being questioned he said, “Momma they put a gun in my mouth and pulled the trigger.”

Nolan McCoy said that Robinson and Dill left the interrogation room with then-deputy Bobby Woodward who put a pistol to McCoy’s forehead and said, “I know you raped that nurse” along with racial epithets.

These statements were found not to be reliable in a wide breadth by Eisele.

Despite mostly denying brutality took place, Eisele did say that two of the men had credible evidence of abuse— Randy Mitchell and Frank King, both of whom hadn’t been in trouble with police prior to the Mason investigation.

King said he was being questioned by Dill and other deputies when Robinson walked into the room and said, “You all ain’t hit him yet?” Immediately, he was slapped so hard that he fell out of his chair, according to his testimony. Dill picked him up off the floor and forced a gun into his mouth and said, “I’m gonna blow your head off.”

In Mitchell’s testimony, he said he too was slapped by Robinson and Dill. He also said deputies had done something peculiar— put a telephone book on his head and slammed their nightsticks on top of the phonebook.

Two other men who came forward also mentioned the use of phone books.

Frankie Webb said each time he denied involvement in the murder, deputies “each took a phonebook and started beating” him on top of the head.

John Edward Walker testified that when he was being interrogated and accused of Greta’s murder, deputies placed a phonebook on top of his head and hit him with a blackjack.

During the evidentiary hearing, state prosecutors put forth 12 deputies who were named as abusers, who didn’t deny that contact happened with the Black men but that they didn’t remember what happened.

Eisele agreed that the abuse of Mitchell and King was possible, but wasn’t convinced that they bolstered Barry’s story of being beaten or that there was a pattern of systemic abuse by Pulaski County deputies under Sheriff Tommy Robinson.

He found that Barry’s lawyers had failed to prove that any abuse happened to him prior to his confession because the men’s accounts were “completely different” and “failed to show any real similarity between the abuse alleged by the witnesses presented and the abuse alleged by [Barry] himself.”

"On the one hand the total record reflects an energetic, effective, comprehensive and professional investigation," Eisele said. "On the other hand there are blemishes on this otherwise impressive record which cast a shadow over the process ... law enforcement officers everywhere and law enforcement itself.”

Calvin Rollins, who was a Pulaski County deputy in 1983, spoke about what he saw the night of the confessions nearly 40 years later. He was in patrol at the time. Despite an ongoing feud with Dill, Rollins' was called in to help with the camera equipment.

While his role in Fairchild's arrest was small, Rollins spoke about what he remembered differently than his earlier testimony, when he said he heard Barry get slapped by Dill, followed by the lead investigator calling the suspect racial slurs.

“The guy that was arrested for it somehow or another had a black eye and broken nose and a busted lip,” Rollins explained. This was something he mentioned in 1990 as well. What happened next was left out of that testimony.

As he was leaving the room after fixing the camera, Rollins said Sheriff Robinson went back in. “He went in there and got [Barry] and brought him out, and the guy was smartin’ off to him and he just grabbed him by the shirt and slammed him up against the wall. And got right up in his face, you know, said a few words.”

In a 1993 interview, Bobby Woodward, a former Pulaski County sheriff’s captain accused of abuse by a few of the men, said “I'm not saying ass whoopings didn't take place. It was a regular routine.”

Woodward’s quote was read aloud to Rollins, followed up with asking if “ass whoopings” did take place under Robinson as sheriff.

“Of course,” he answered.

Rollins also explained a tactic we’d only seen in documents, not quite understanding it would take on a life of its own.

“Phonebooks work. Yellow pages especially, because they don’t leave bruises. You can smack somebody right square on top of the head and they’ll tell you anything you want them to,” he said.

“Of course, I never did that.”

Howard was able to recount the same murmurs she heard as a reporter involving the use of phonebooks in interrogation rooms.

“What it did is it would scramble the brains and it would show no bruises and no evidence of abuse whatsoever. But it would be extremely painful for the recipient of that treatment,” Howard said.

In 1989, a year before the men’s testimony would become public record involving telephone books at the sheriff’s department, Robinson denied ever beating Fairchild in quotes to the newspaper.

“How can you beat someone up without marks?” He asked. “Explain that to me.”

A year later, when the press was insistent that Robinson address the abuse rumors, he would emphatically deny ever beating an inmate. However, known for his unpredictable antics in the press, the former sheriff replied to a newspaper reporter “If I hit someone, I wouldn’t tell you.”

The former deputy who initially told the FBI about abuse within the sheriff’s office told the court that he hadn’t come forward sooner because he thought Barry was guilty. Rollins said he also thinks Barry committed the crime, but the evidence against him “wasn’t enough to write him a parking ticket.”

To the veteran turned career policeman, Rollins said it was Dill’s judgment that soured the investigation altogether.

“You know, there might be 13, might be 23. But you can't lump all of them together,” Rollins said of the men who came forward alleging abuse, a large percentage of whom mentioned Dill by name.

“You have to have enough cognizance to pick out the bad ones from the good ones. Dill didn’t have that.”

The Evidence

What has made this case perplexing is that prosecutors and the district court have said on the record they don’t believe Barry to have pulled the trigger and have even gone far enough to assume Barry was shocked when he heard the gunshots that resulted in Greta’s death.

In fact, a scenario where he was an active participant in her killing has never been put forth.

Since charges were brought against Barry for his role in the murder, there hasn't been a public investigation into who pulled the trigger that night. We've reached out to the Pulaski County Sheriff's Office regarding the status of the case, but haven't heard back at the time of publishing.

In 1983, you could test semen samples but you could only narrow it down by blood type. In Greta’s rape and murder, the state crime lab was able to test semen samples that were found at the scene but wasn’t able to definitively name a suspect.

None of the fingerprints found inside Greta’s car or at the scene of the crime could be linked to Barry. Investigators believed that was because he and his accomplice threw their gloves out of the window while driving away from the murder, gloves that were never found by police.

During his recanted confessions, Barry is asked about Greta’s watch which reportedly was taken after her death. Barry said his accomplice had given it to him and that he sold it to his sister, Irene.

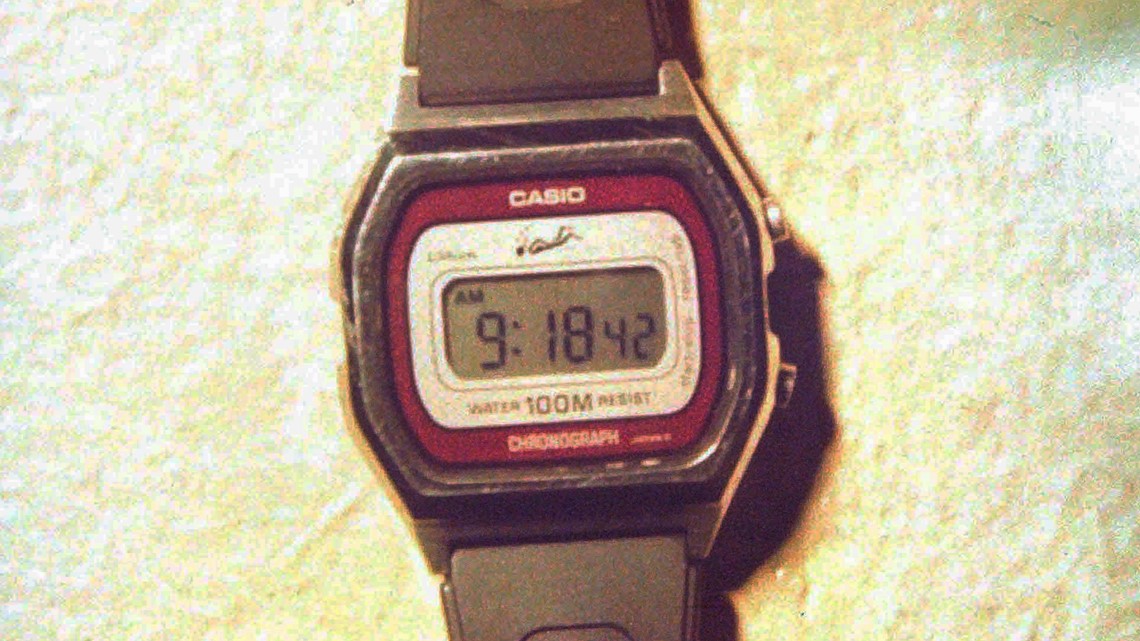

The morning of the confessions, police went to Irene’s home and located a red and black women’s Casio scuba watch she said she paid $20 to Barry for. At the 1983 trial, Greta’s family identified the watch as hers.

In the Pulaski County Sheriff’s Office files that were uncovered years after the trial, more documents were found that weren’t given to the defense in 1983. Among those files included witness statements describing the watch Greta was wearing the day she disappeared as a gold, shiny watch.

Greta’s mother would later testify that she didn’t remember the watch being red.

“It turned out that there was a note in a police file that there was a difference between the watch that Fairchild's sister had and the watch that Mason wore,” said Mara Leveritt. “The [note] was in the police file and not turned over to the defense.”

Leveritt is an investigative journalist known for her book The Devil’s Knot, an in-depth account questioning police procedure within the West Memphis Police Department during the 1993 murder investigation of Damien Echols, Jason Baldwin, and Jessie Misskelley.

“There was a murmur of, ‘What was up with the cops in general?’ at the time. But then, a particular concern about Robinson,” Leveritt said.

She was a newspaper reporter when the news of Pulaski County investigators withholding evidence was uncovered in district court.

“That should have been the end of the story. And heads should have rolled. Heads all over the place,” Leveritt said. “And, of course, that's grounds for at minimum, a retrial.”

Barry’s sister Irene testified to buying the watch from Barry, who she believed had won it at a gambling hall before the murder. She said she felt pressured by deputies to say it was after the murder.

Barry’s confessions, the informant, and the watch are what sealed his fate in the original jury trial.

Those factors, however damning they may sound alone and without contention, still beg the question: If not Barry Lee Fairchild or Harold Green, who killed Greta?

The Killer

Larry Dill and Tommy Robinson have gone so far as to say publicly they have an idea but alluded to the lack of an arrest as beyond their control.

Based on documents acquired from the Arkansas State Police, there was an investigation into Barry’s younger brother Robert as the accomplice responsible for the murder.

State police had transcripts of two interviews between Pulaski County deputies and inmates who claim Robert bragged to them about kidnapping, raping, and killing Greta while in prison in 1983.

The interviews took place in September 1983, a month after Barry was sentenced to death.

The first inmate told the deputy that he shared a cell block with Robert Fairchild, who had struck up a conversation with him after everyone had fallen asleep.

The inmate asked Robert why Barry hadn’t turned in the person who pulled the trigger in order to get a lesser sentence, “then [Robert] looked at me and gave me a little funny eye look and went to grinning,” the inmate said.

During the years that Barry was in the press for appeal hearings, the frequent topic of his little brother’s involvement would rise back to the surface.

“You would hear this again and again, that of the two brothers, one was much more assertive and aggressive. And if there was someone that was going to get into trouble, that was going to be Robert Fairchild,” Phoebe Howard said.

The inmate said Robert told him on the night of the murder Barry said to “leave the girl alone.” When Robert said they needed to kill her in case she could identify them later, Barry reportedly refused, saying, “leave her like she is.”

There had been an argument, Robert told the fellow inmate, but that eventually, he had conceded to just leave Greta in the farmhouse and drive away with her car— only after raping her one more time.

Robert allegedly left Barry in her car and went back into the farmhouse, raped her, and shot her.

“The reason I went and talked to the corrections officer was because, you know, he was bragging about it,” the inmate told investigators.

In a separate interview with another inmate who came forward about a Robert jailhouse confession, he said he started the conversation with Robert. “I got to talking about his brother Barry and I said, ‘Man, I don’t believe Barry did nothing like that, man.’”

Robert reportedly responded, “I’ve known you for a long time, so I’m going to tell you, man… I’m the one who killed the broad.”

In this inmate’s statement, he gave accounts details that are incorrect, telling deputies that Robert said they kidnapped her and brought her “back to her house.”

He said Robert mentioned that only he had raped Greta, and the second time is when he shot her in the head.

“Do you think he’s more capable of doing that than Barry Lee?” The deputy asked, repeating the question he asked the previous inmate.

“Yes, Sir. Robert Lee was always running around getting in trouble, messin with folks… always fighting, getting in brawls,” the inmate said. “Barry Lee, he wasn’t, he was quiet.”

In August 1995, Jack Gillean, a former prosecutor who argued for the state in district court against Barry for years, was now the Executive Assistant for Criminal Justice with the governor’s office.

In a letter, Gillean said, “During the days leading to Barry Fairchild’s execution, this office received a letter from Chaplain Dennis Pigman.”

Pigman said he’d met with the Fairchild brothers nearly every week for six years as a chaplain at the prison.

The chaplain sent the letter to the Arkansas governor at the time, Jim Guy Tucker, on August 25, 1995.

“The information I want to share with you is that as a result of counseling and contact with Barry and his brother, I have been informed that Barry did not murder the nurse, but he did cover for his brother who did murder the woman. I understand Black culture and Barry’s need to cover for his brother.

I am requesting your consideration of these facts and that you would stay the scheduled execution.”

Gillean said, “I am not sure what to make of Chaplain Pigman’s letter, but felt I should bring it to your attention for whatever value it may be to you.”

Lonoke County Sheriff Isaac responded by saying, “The question brought up by Champlin [sic] Pigman to Governor Tucker has been common suspicion among law enforcement; as well as the Prosecution for over (12) twelve years, however, without material evidence or collaborating witness to a statement that was never written by Barry Lee Fairchild; the question is mute… My mind is at peace that justice was properly preserved.”

The Execution

Justice is a resounding theme in the case of Greta Mason’s brutal murder and Barry Lee Fairchild’s years in a system that bears its name.

To Judge Eisele, who eventually commuted Barry’s sentence to life in prison only for it to be overturned due to a technicality, “truth is the only secure and durable path to justice.”

In 1990, Robert Lee Fairchild was sentenced to life in prison for the kidnapping and rape of a 17-year-old boy.

Nine years later, while serving his sentence, Robert stabbed a prison guard with a shank and beat him in the head with his heavy-duty flashlight “at least ten times,” according to witnesses. Robert reportedly dragged the prison guard’s body across the prison floor and dropped him to go through his pockets.

The guard was given a 20% chance of survival by medical personnel. After doctors removed some of his brain, he was able to recover. The man became blind in one eye, confined to a wheelchair, and unable to control outbursts and cognitive functions, changing his life forever.

A prison official asked Robert why he attacked the prison guard in the moments after he was detained. “I'm tired of being here,” he said. “I was trying to go out like my big brother.”

Robert was sentenced to life in prison without parole.

On August 31, 1995, Barry was executed by lethal injection. Three weeks before, the clemency board voted 4-3 in favor of denying clemency. It was the closest vote to grant clemency for a death row inmate in Arkansas at the time.

In the hours leading up to Barry’s execution, prison guards took notes of each moment. On August 29, a guard wrote Barry mostly stared at the ceiling and smoked cigarettes.

Fairchild received a cigarette and stated that if he knew his brother was going to turn out the way he did, the guard wrote, "that he would not have took [sic] the murder charge for his brother.”

The next day, on the afternoon of his death, Barry is noted as saying he has no hard feelings toward his brother for “letting him take the charge for the murder.”

“He continued to state that if he were to die tonight that he had made peace with himself and the Lord… if he was to die tonight it was just his time.”

Justice is a system of rules, laws, and obligations to people with the privilege of seeing it as a tangible ending to a worthy fight. For others, the idea of justice is out of reach— a hopeful feeling that they’ll never have.

To an Arkansas sheriff, Greta’s murder investigation with an outcome tangled in doubt leaves him with peace that justice is “preserved.” But the questions arise: Justice for who, and what is it preserving?

“In Greta's case, there is no justice. She's dead,” her brother Billy said. “The only justice is to do something about it in today's world. And to me, that's the only justice we can give her.”