ATLANTA — Active shooter drills are a common part of safety plans at schools in Georgia and across the entire country.

Researchers with Georgia Tech's College of Computing said as drills have increased over the years, there has been little scientific data examining the mental impact of the drills on students and staff.

"People have been reporting that these drills are having a negative impact on their mental health. This wasn't empirically validated," Associate Professor Munmun De Choudhury said.

A new study, though, published Thursday by Everytown for Gun Safety, features scientific findings from research De Choudhury and her research team in the College of Computing's Social Dynamics and Well-Being Lab recently finished.

"Different symptoms of stress, such as anxiety and depression, we could measure those attributes based on the words, and patterns of words, that people used in their social media posts," De Choudhury said.

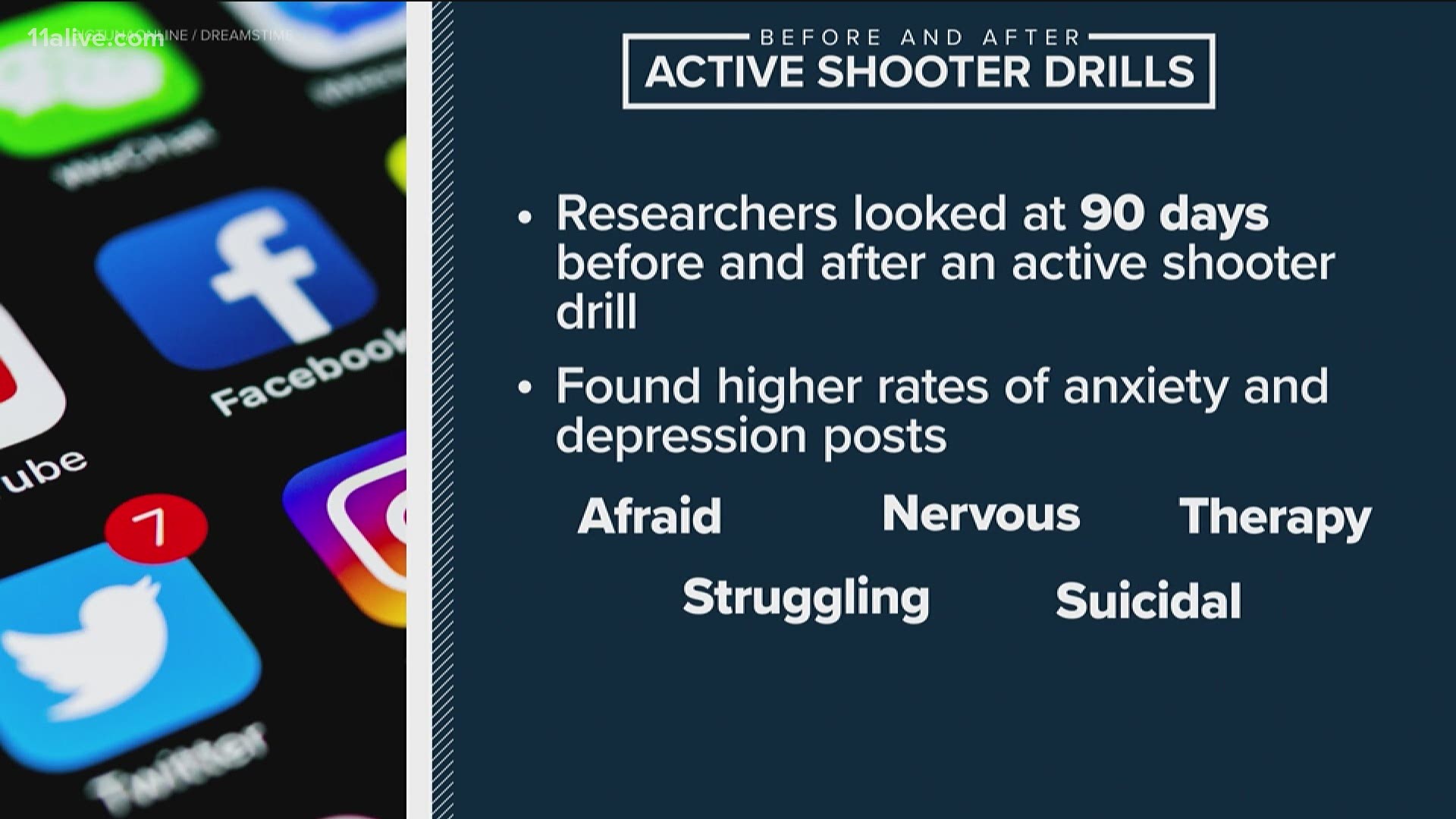

The findings showed in the 90 days after experiencing an active shooter drill in a school, people's social media posts signaled increased anxiety, stress and depression.

As they conducted their research, the team at Georgia Tech analyzed nearly 28 million social media posts between Twitter and Reddit, using methods called psycholinguistics analysis and machine learning - which allowed them to efficiently process large amounts of social media data.

The data used was from the 2018-2019 academic year, spanning 114 schools in 33 states. De Choudhury and her team compared the language people used on social media in the 90 days before a drill and 90 days after a drill.

"What was surprising to us was the change in the levels of stress, and anxiety and depression," she said. "It wasn't a small change. It was significant compared to what it was before the drills."

The results showed a 42 percent increase in anxiety and stress; depression increased 39 percent; and posts about health concerns and fears about death also spiked, increasing 23 and 22 percent respectively.

Words such as "afraid," "nervous," "therapy," "struggling" and "suicidal" were used more frequently in the 90 days studied following drills.

People were identified as being connected to a school through their social media bios, if they followed the school's Twitter account, mentioned the school in posts or geolocation showing their posts were coming from the school.

The posts from people connected with the schools were then compared with a control group of people in the same community that didn't have a connection with the school.

"We found that, compared to that control, the increases we saw were still valid," De Choudhury said. "In the control, we didn't see these kinds of changes, which would rule out situations where people were feeling overwhelmed due to another unfortunate incident in the community and not necessarily due to the drill."

Part of the team of researchers working on the study was Georgia Tech postdoctoral fellow Mai ElSherief and PhD candidate Koustuv Saha.

ElSherief said they collected the data in a way that allowed them to not re-traumatize anyone - as they gathered social media posts people had already made - meaning they didn't have to ask questions that may trigger emotions or skew their results.

"Stress, anxiety, depression can manifest in different ways, and using an unobtrusive method with collecting these data, and, as you mentioned, it is a large data set makes us very confident in our results," ElSherief said.

Saha said he had a hypothesis their research would show increases in serious mental health issues, but the magnitude of the changes caught him off-guard.

"The levels - the 30 to 40 percent increase - it is both alarming as well as surprising for us," he said. "This is huge, and this needs to be taken care of as soon as possible."

ElSherief also found the results showed higher changes in mental health than she expected before the study was completed.

"While it was surprising for us, it wasn't really surprising for them," she said.

After conducting their research, the team presented their findings to people who had previously participated in active shooter drills at schools.

"They said these results make sense, these are spot, on and it really resonated with what they were going through," ElSherief said. "This also adds this validity by involving these people who were affected and they experienced that first-hand."

Saha hopes their research can now be used as governments and schools create or adjust policies and plans for active shooter drills in the future.

"When thinking about policy changes or what could be done to address these mental health or psychological challenges that people may face out of these events," he said. "Maybe even consider conducting these events in a more grounded or structured approach so these kinds of mental health or psychological impacts that can happen can be minimized."