EAST COBB, Ga. — Georgia reopened the economy with the hopes that social distancing and contact tracing would keep the virus at bay.

With 3,413 new cases reported on Tuesday, it doesn’t appear the plan is working.

The state says it wants to hire 700 more contact tracers to keep up, bringing the total to 2,000. The question now, will it be enough?

The Reveal investigator Rebecca Lindstrom began to look into the state’s contact tracing program when one of her friends, Donna Walens, got sick with COVID-19.

Walens had a small dinner party at her house. Three days later she was hit with a crippling headache. She had problems breathing, was overly exhausted and developed a rash.

“I can’t taste anything, and I like food. And I can’t smell anything,” added Walens.

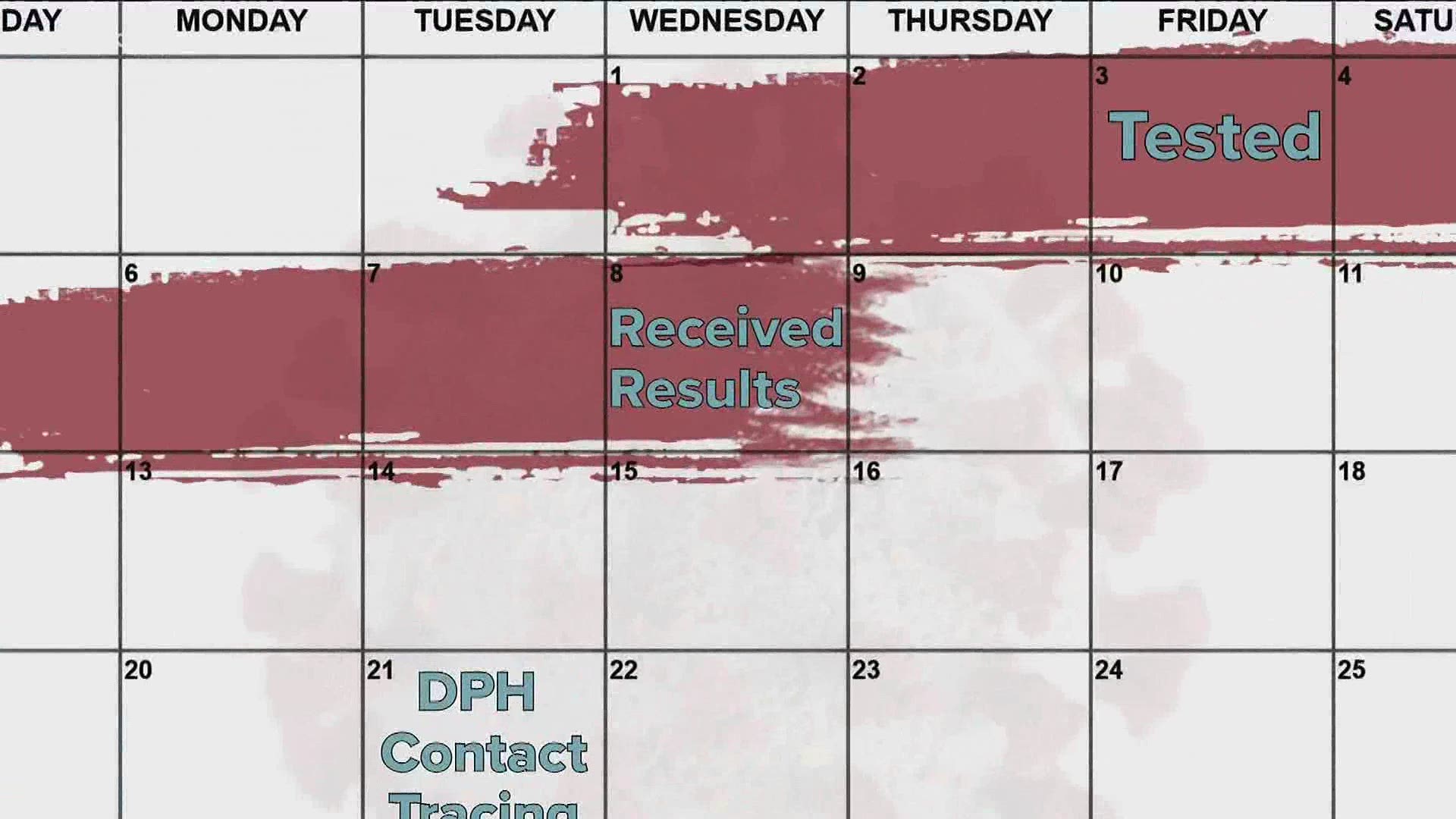

She went for a test and received her results five days later. In the meantime, she made phone calls to alert anyone she’d come into contact with.

“I contacted everyone I’d been around and let them know just, you know, to be safe on getting tested," Walens explained. "It’s the right thing to do, but it was very embarrassing."

When almost two weeks had passed, Lindstrom wondered where the Department of Public Health (DPH) was in the process. She had spent time with Walens before symptoms appeared, but had yet to receive a call from a contact tracer. The process, it seemed, had been left to the integrity of the individual.

In a public briefing last Friday, Dr. Kathleen Toomey who heads DPH reported, “to date, we’ve interviewed more than 40,000 individuals with COVID-19 and identified 86,200 contacts.”

While it may sound like a lot – it only represents about 32 percent of all cases in the past month.

In a written statement a DPH spokesperson wrote, “As the cases of COVID-19 increase daily by the thousands, it becomes increasingly difficult to keep up.”

Another problem, as the state works to get more labs online, test results can take up to two weeks. At that point the risk period – and the state’s ability to do much about it, has passed. When DPH does get the information in time, it said some people don’t want to pick up the phone.

No one contacted Walens to let her know she might be infected. She found that out on social media. But she’s glad she made the effort to alert others.

“I think they were glad that I told them, and that way they could see if they were getting any symptoms or go get tested themselves," Walens said. "I think that they appreciated it because it shows that you care."