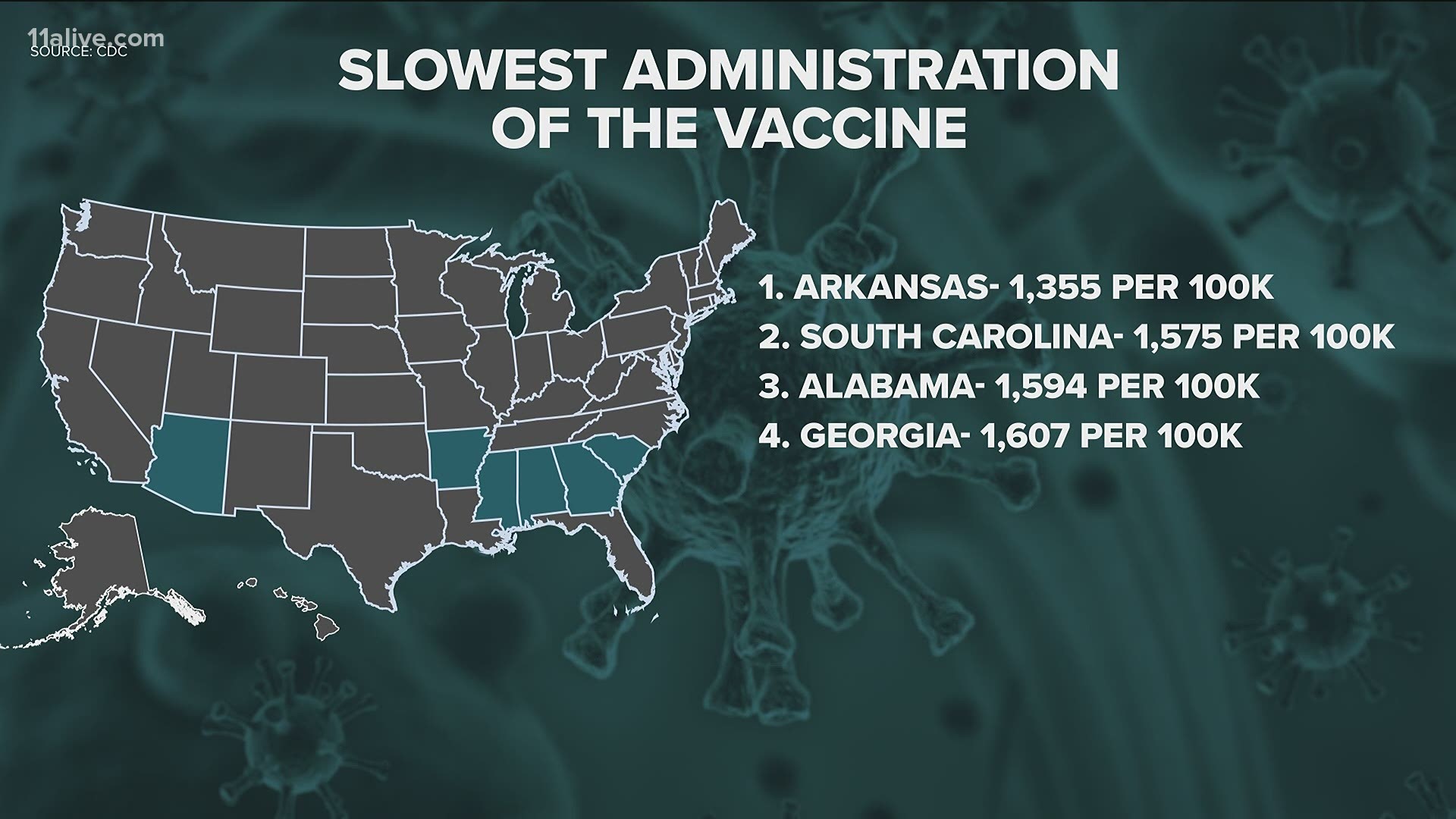

ATLANTA — As of Tuesday, Georgia is the fourth slowest state in the United States when it comes to providing people the COVID-19 vaccine. That is some progress after the Peach State fell dead last nationwide on Monday afternoon.

According to a map from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Georgia shows the rate of vaccinations is around 1,607 vaccinations per 100,000 residents.

In comparison, Florida, just next door, which is also currently vaccinating those age 65 and older, is vaccinating people at a rate of 2,949 per 100,000 residents.

From public health experts to state representatives like Democratic state Sen. Nan Orrock, the common reaction is that Georgia should be doing better.

"We cannot stand for Georgia being at the bottom of the list on getting this vaccine out to Georgians," Orrock said. "I mean, the CDC is headquartered here -- in our state. We have great universities, great scientists, great medical community providers, and pharmacies. We have the means to get this out. We need the plan and leadership to do it and do it now."

Public health expert Dr. Harry Heiman and supply chain professional Dr. Pinar Keskinocak echo Orrock's sentiment. They say Georgia is falling behind for several reasons.

"What we are seeing with vaccinations is a classic, textbook definition of supply chain failure," said Dr. Keskinocak, logistics and supply chain expert at Georgia Tech.

First, they say the state didn't have a proper vaccination plan from the beginning, and now, that fact is showing.

"Part of the plan needed to be aggressively working with local public health departments to improve their capacity and infrastructure to manage this kind of thing," said Dr. Heiman of Georgia State University's School of Public Health. "I don't think that was done."

They add that state and health officials are not doing enough to encourage communities that the vaccine is safe.

"We're seeing a hesitancy for people to take the vaccine, even some of the highest-risk people, and that's a communication failure on the part of both the public health and political leadership," said Dr. Heiman.

RELATED: 'It’s a combination of challenges and risk factors' | COVID disproportionately affecting Latinos

The largest problem of them all, they say, is the underinvestment in public health. It's a sector they say that has been underfunded for decades but the pandemic is bringing it to light.

"It's very hard to do the rollout while dealing with high numbers of hospitalizations," said Dr. Keskinocak, who is the director for Georgia Tech's center for health and humanitarian systems. "Georgia is a large state and we have a lot of people with underlying chronic conditions."

Both of them say there are several ways Georgia can speed up the administration of vaccines, but it will take time, money, and resources.

"COVID-19 response nationwide has been tampered since the beginning due to lack of coordination, lack of funding and misinformation," Keskinocak said.

They both agree that more money needs to go into solving this crisis and that lawmakers need to be the ones to spearhead these efforts.

"One of the things the legislature needs to seriously look at, is our investment in public health, public health infrastructure, the needed investments to ensure Georgians have access to vaccinations and that we're able to respond to this pandemic that has now 5,500 people in hospitals across our state, on average," Dr. Heiman said. "About 70 people a day are dying, and on average about 10,000 people a day are being newly infected."

Part of those funds, they say, should go towards education about the vaccine. Right now, there is still a lot of hesitancy to receive it, especially in rural counties.

"We need a much more aggressive approach to engaging communities," Dr. Heiman said.

"Us getting up to speed is a combination of more resources, better coordination across the front groups and organizations," said Dr. Keskinocak.

Experts add that more investments are also needed to go into hiring more people, training more of them to vaccinate, and bringing in IT staff to help with the websites -- which became especially apparent after several sites from different health districts crashed on Monday morning.