#HopeOverSuicide: It's time to talk

It's hard to talk about it. It's hurting our community. It's time.

It's time to talk...

ATLANTA – It’s a story we’re not supposed to talk about. It’s a story you rarely hear about in the news. It’s a story we’re stripping away the shadow and stigma from.

It’s hard to talk about it.

It’s hurting our community.

It’s

#HopeOverSuicide

and it’s a conversation worth having, now, more than ever."I think there was for a long time the perception that if we talk about it, we give people ideas and then they will act on, we know that to be false at this point. The more comfortable people feel talking about suicide, the more likely they are to reach out to someone at the moment they need help the most," psychiatrist Dr. Ben Hunter, with Skyland Trail, said.

On average, 121 people take their lives every day.

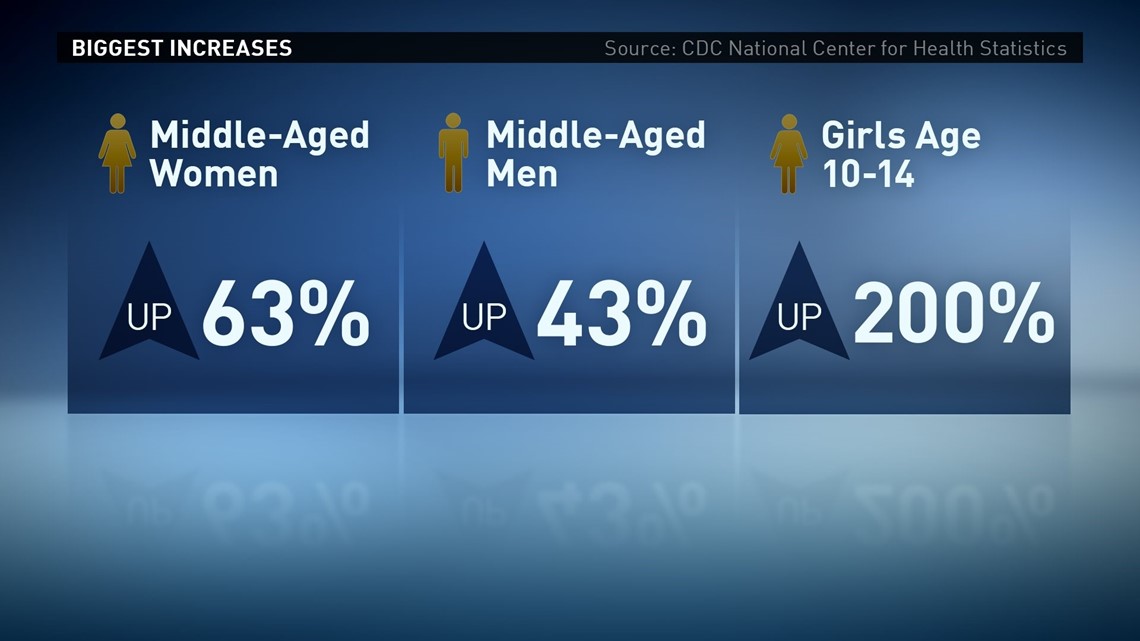

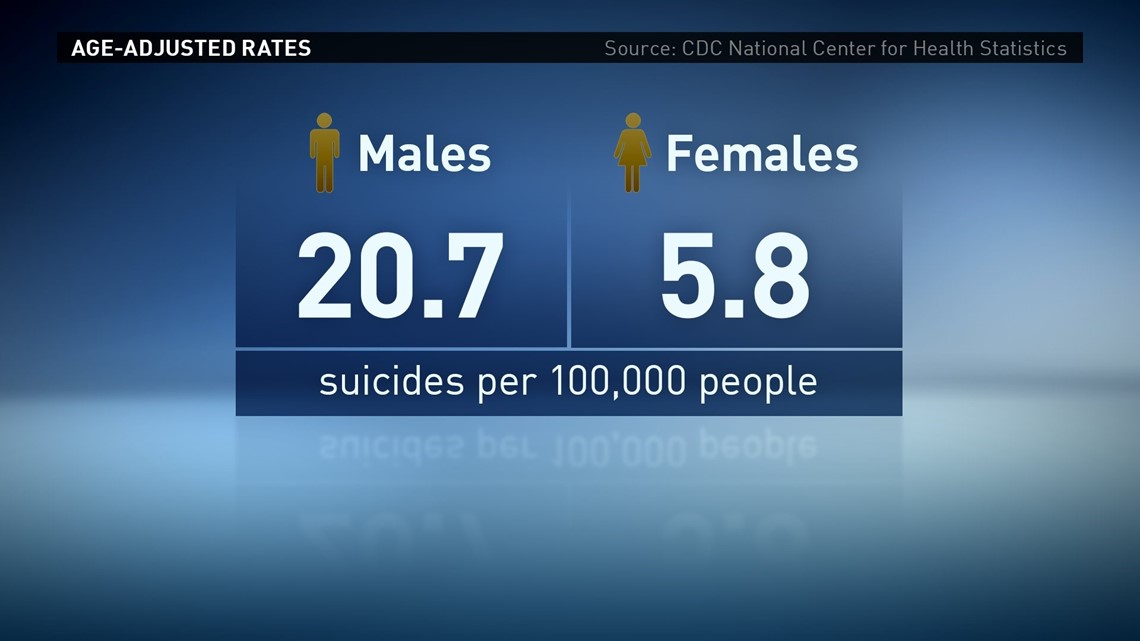

According to the CDC, suicide rate between 1999-2014 is up 24 percent, from 10 1/2 to 13 per 100,000 people. Middle-aged women saw the largest increase with 63 percent up. Middle-aged men were up 43 percent. Girls, ages 10-14, have increased by 200 percent.

In 2015, suicide claimed

44,193

deaths in the country. Rates of suicide from 2000-2015 have increased by more than 27 percent.Surviving the heartbreak

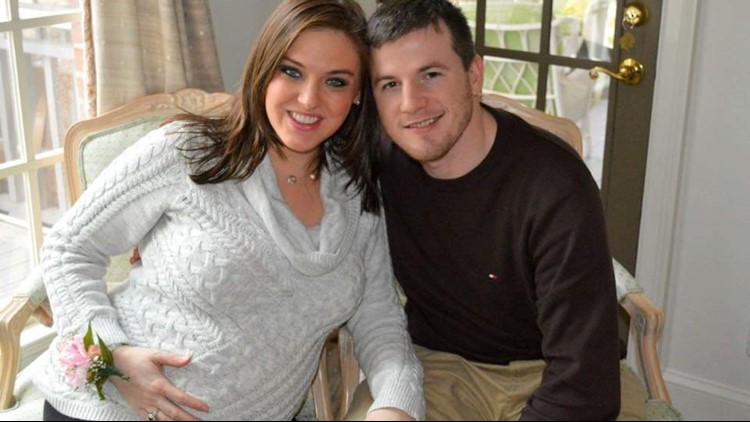

Hannah Piercy, of Cumming, Ga., knows the numbers well.

She lost her husband, Caleb to suicide in January 2017. Now, she's raising her two children as a single mother.

But, she doesn't feel alone.

"I haven't let go of Caleb," she said. "I want them to know their dad is still here. He loved them so much, so, so much."

Hannah's husband Caleb died by suicide when she was pregnant with their son Wally, and their daughter Azlynn was only 1 1/2 years old.

"It did not make sense until after it happened, and then it's like all the puzzle pieces fell into line, and it's like, 'Oh, my god,'" Hannah said.

Hannah and Caleb met through an online dating site and fell in love fast.

PHOTOS | Hannah creates hope from her loss

He put himself through Georgia Tech to become the first in his family to graduate from college.

"And then he got his dream job as an engineer with Harley Davidson. He loved motorcycles, he played guitar, he sang," she said. "We dove head-first into starting a family."

But Hannah said, she started to see a change in Caleb. It scared them both.

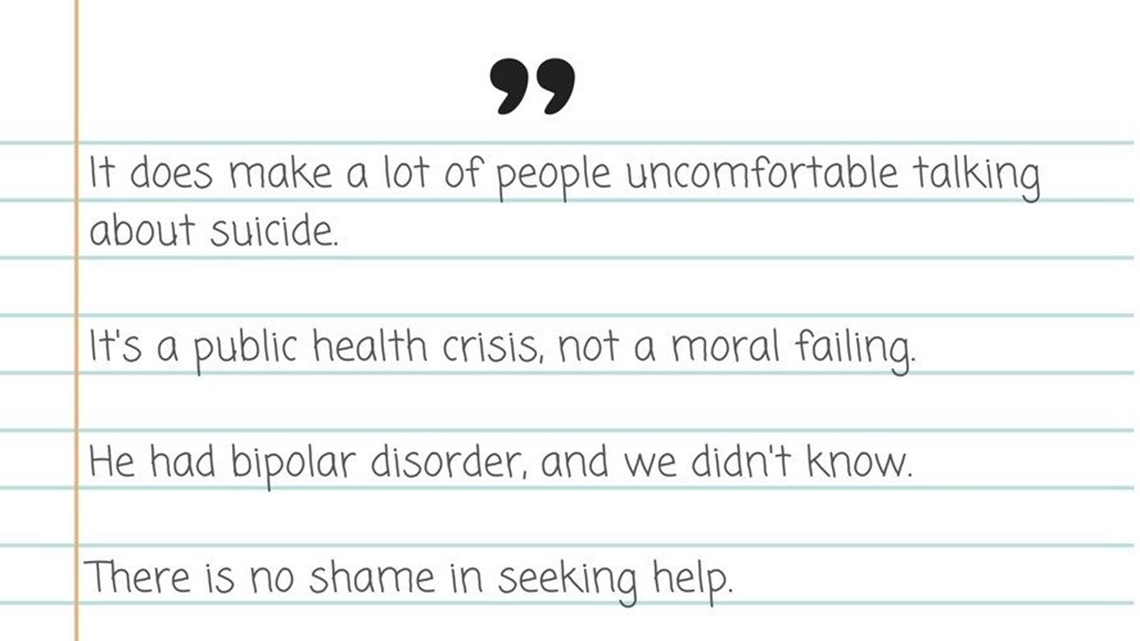

"He had bipolar disorder, and we didn't know."

"He would get this look in his eyes when this happened. His eyes would go so dark, and he wouldn't look like himself."

"He did not want to be sick. He was scared of being sick. He was scared of what that would mean."

Caleb eventually agreed to start therapy. He went to two sessions before using a gun to take his own life.

"I remember the shock of when he first did it," she said. "I wasn't present mentally. It was like this feeling, this thick, heavy fog and depression and felling like how do you function."

She said she got to a point when Wally was born, that she wanted her life back--and she was ready to talk.

But, Hannah did more than talk about it.

She created a Facebook group called "Stigmatized" to document her journey as a suicide survivor and connect with others impacted by suicide.

"Literally every person I talk to has some sort of story to tell. Maybe they haven't lost somebody, but they know somebody that struggled, they themselves have struggled."

In two months, she said 24 suicides that have been prevented through the outreach of the Stigmatized community.

"We are not mental health professionals, and I have to stress that we are just people that care," she said of the Facebook group.

"We're here to help."

She even used Facebook live to show how the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline works.

"We can call ourselves to talk about a loved one, correct? Absolutely."

"I did the very best I could by my husband with what I knew then. If we were to start educating people more, letting them know what some of the warning signs and red flags look like, I believe we could help prevent more suicides."

"There is no shame in seeking help," she said.

A place for hope, intervention

Deb Stone works for the CDC's suicide prevention department. And while most would think that she works in one of the most depressing departments, she said, it's about more than that.

"When I work in suicide prevention, and people ask if it's depressing, and I say no, it's not depressing at all because hopelessness is depressing. There's so much more we can do to help people so they never feel suicidal in the first place," Stone said.

"At the CDC, we collect data, we research the factors that contribute to suicide. We develop and test interventions and then we get the word out," she said. "I've seen depression and despair up close. And I've also seen people overcome those things. I go to work every day to give people hope."

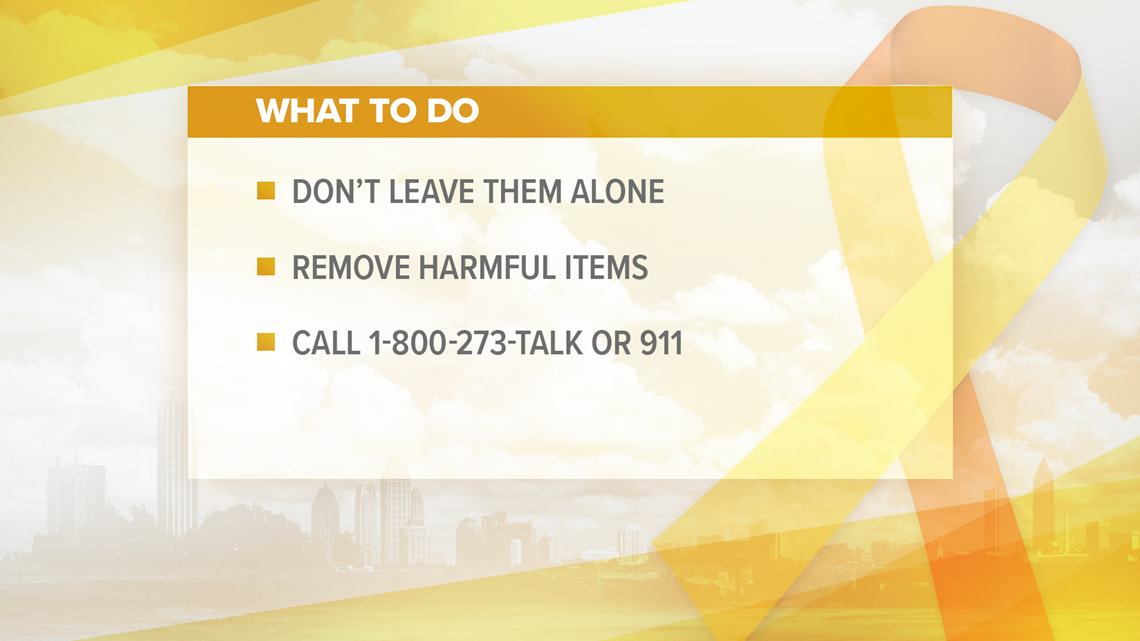

>>>National Suicide Prevention Lifeline | (800) 273-8255

The number for the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline is also the name of a powerful suicide prevention anthem - released earlier this year by the rapper Logic with Alessia Cara and Khalid.

The video of their performance on MTV's Video Music Awards in August has more than 8 million views on YouTube.

They sing, "I finally want to be alive, I finally want to be alive, I don't want to die today. I don't want to die."

Source of strength

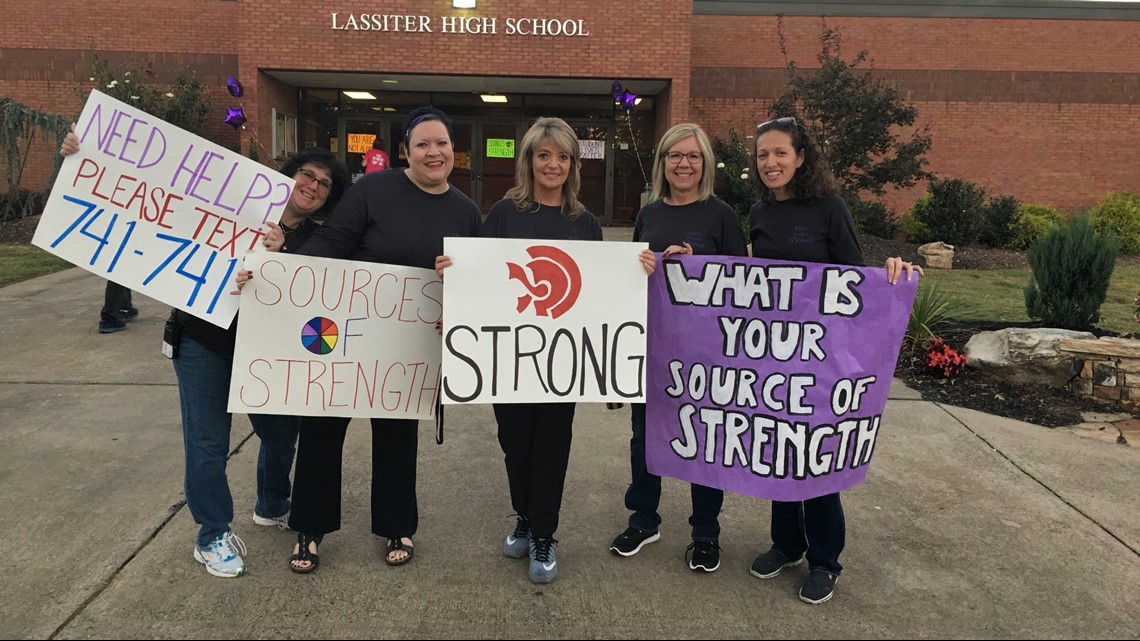

Lassiter High School is the latest to embrace a national suicide prevention program after losing a current and former student to suicide last year.

Lassiter students are learning how to use those strengths to help others.

"I definitely think it's good to remember to always be kind to everyone because you never know what somebody is going through, you never know much they're hiding," Skylar Umstead said.

Lassiter embraced a national program called Sources of Strength, a national suicide prevention.

"We had a really tough year last year - losing a student, losing a former student - our students really grieved over that, and they wanted some help, too. They wanted to spread the word of kindness and to be helpful to each other and to be there if someone's feeling upset, depressed," Dr. Angela Bare, Lassiter's assistant principal, said.

Forty teachers and staff members have gone through training to become adult advisers. Students play a critical role, too.

"It's not just kids involved in everything. We're pulling in kids that have never been involved in anything, but," Bare said. "You know, they want to help. Having that presence in every peer group in the school, we hope that will be helpful."

Sources of Strength took center stage during Lassiter's varsity game against Roswell High School in September.

"We handed out over 1,000 baggies of purple confetti," Bare said. "Both student sections at the first kickoff threw up the purple confetti, and it was just like, a message of we have to be there for each other."

Roswell High lost a student to suicide a week before the game.

"I've had friends that have had mental health problems, and I've known people that have attempted or committed suicide, and I think it's not something we should be putting on the back burner because it's a growing problem, clearly. And nobody that feels that poorly should be ignored," Umstead said.

Umstead is a senior and one of the first students trained as a peer leader.

"A lot of kids don't go to adults because they're worried their parents might find out and what might happen, so they go to their friends, and it's good to have people who know how to handle it, and know when a situation is serious enough to take it to an adult, so that it can be taken care of," he said.

"A lot of kids struggle with social anxiety at school, They're trying to fit in," Bare said. "If there's anything we can do from a school perspective to provide some help, resource, that's what we want to do."

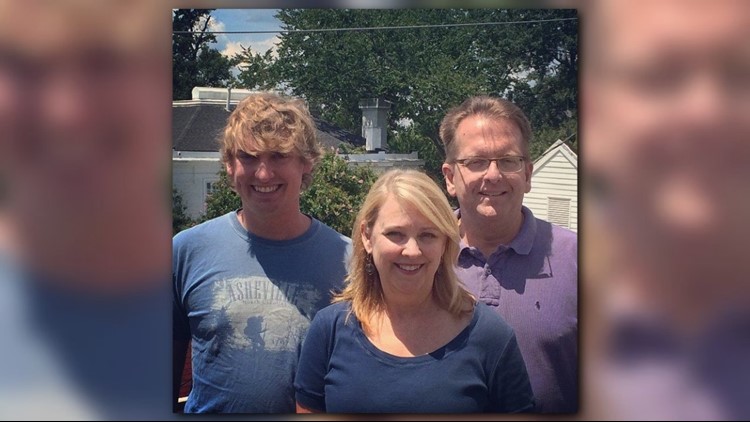

A family's journey

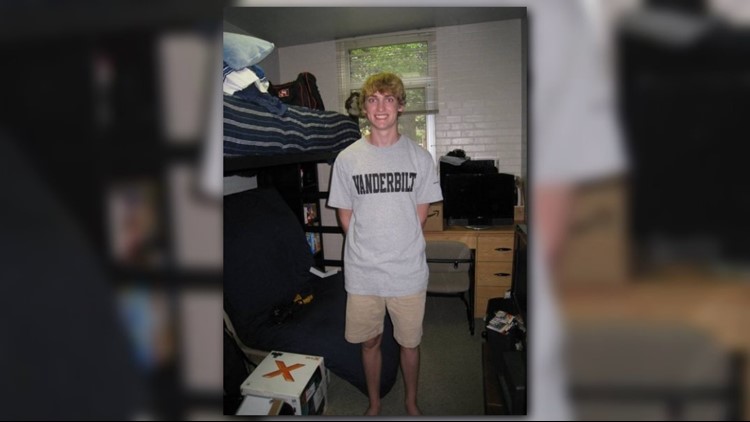

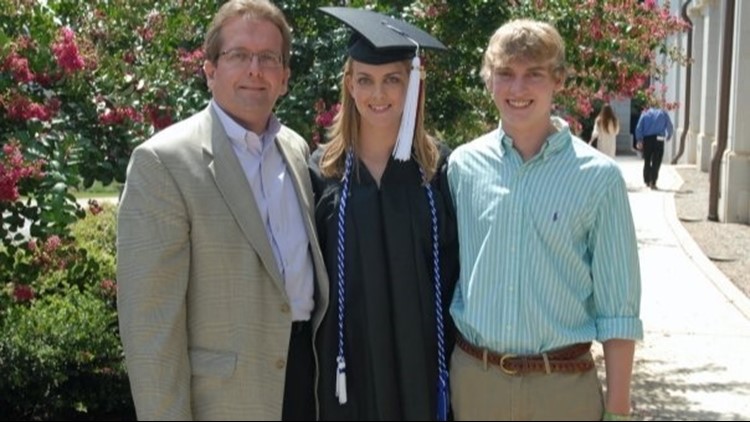

Kyle Behm started having suicidal thoughts during his sophomore year at Vanderbilt. He went to his parents, sought treatment and found his way back.

Now, he's tired of the silence when it comes to suicide, and ready to begin the conversation.

"It does make a lot of people uncomfortable talking about suicide. It is stigmatized. When a loved one commits suicide, it becomes sort of a family secret," he said.

PHOTO | Kyle Behm seeks help, treatment

But Kyle's family is different. They want to talk about it.

In fact, his dad, Roland Behm, serves as chairman of the Georgia Chapter of the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention.

"It's something that affects all of us. Not just them. It's us. It's our family. Our sons, our daughters, our mothers, and fathers."

The Behms have learned through experience that talking about suicide can be a lifesaver.

"Knowing that I wasn't alone feeling, this served as the foundation for seeking help."

Kyle was a sophomore engineering major at Vanderbilt University when he began to struggle with anxiety. By his junior year, his symptoms became more extreme. He suffered from delusions and hallucinations. He even considered suicide.

"I couldn't focus on my work. So that was my external indicator that it's like I either had to quit in general, give up, or I needed to reach out to somebody," he remembered.

He did reach out by sending an e-mail to his mother.

Roland responded to the email:

"First and foremost, we love you very much and are so proud to have you as our son. Second, thanks for reaching out and speaking directly about a difficult issue. Third, we're sorry that you're having a very difficult experience and we will do everything we can (and that you will allow) to move to a much better experience."

He ended the e-mail with, "You are so cherished."

"Looking back, that's probably one of the better things we did, which was not to recoil, to be concerned but not to roll that back and say you shouldn't feel this or you shouldn't do that," Roland said.

But, their lives would grow more complicated, before it would get better.

Kyle took medical leave from Vanderbilt in his junior year.

He was working with a psychiatrist and therapist in Atlanta when he experienced a psychotic episode in December 2010. He was hospitalized for several days at Ridgeview Institute in Smyrna, Ga., and started an outpatient program at Skyland Trail, a nonprofit mental health treatment center for persons 18 and over.

Diagnosed with bipolar disorder, a chronic and recurrent mental illness, Kyle was prescribed medication and engaged in both group and individual therapy during his four-month stay at Skyland Trail.

Subsequently, he went back to school and graduated with a degree in mechanical engineering from Mercer University.

"The productive things was just listening, listening to what I had to say, no judgment and just being there," Kyle said.

"I'm doing very well. By the standard metrics, I have a lot of friends, I have a lot of people who care about me very deeply," he continued.

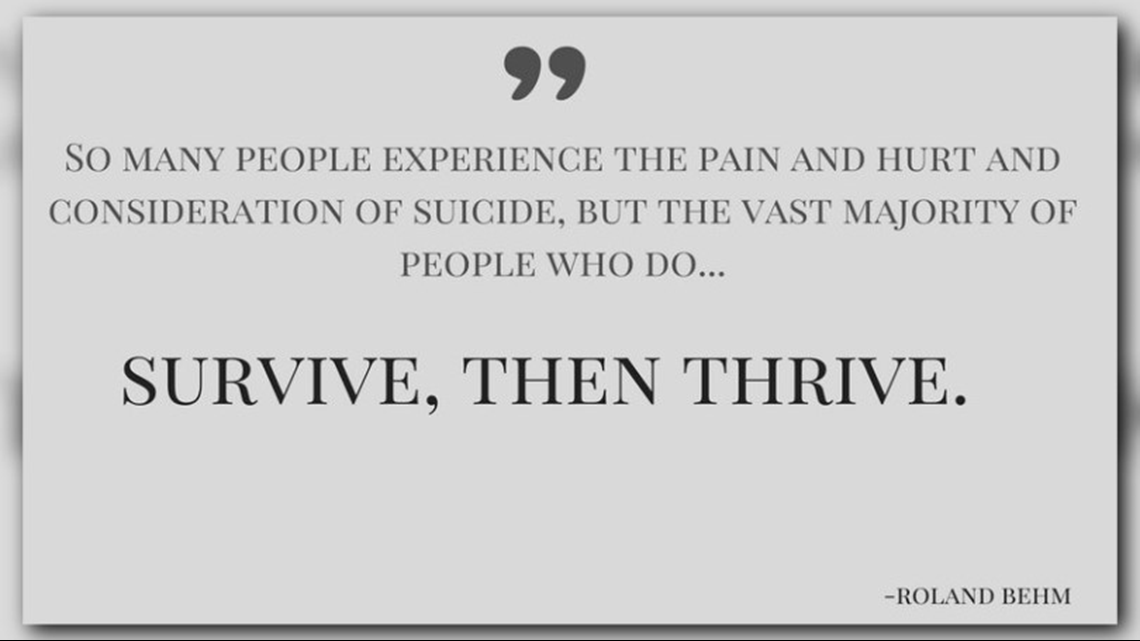

"So many people experience the pain and hurt and consideration of suicide, but the vast majority of people who do - survive, then thrive," Roland said.

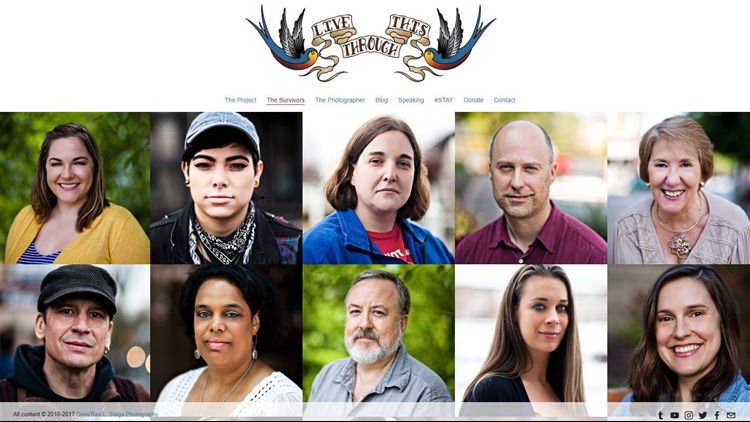

Live Through This

More than 1.3 million people attempt suicide each year.

Some of the faces of suicide attempt survivors are part of a project called "Live Through This." It's a collection of portraits and stories by Dese'Rae Stage, a survivor who wants to break the silence and bring people hope.

"Live Through This" is a project about life on the other side of a suicide attempt.

"The people who are part of this project could be anybody, your brother, your mom, your neighbor and you would never know because everyone's so afraid to talk about it," she said.

She has photographed people from 35 U.S. cities--182 people who have said, "Yes, I want to do this, I want to tell you my story."

"My ultimate vision for this project is to save lives," she said.

PHOTOS | Live Through This project by Dese'Rae L. Stage

PHOTOS | Live Through This project

Dad to parents: Is your daughter OK? Check again

Alex Blackwell told her boyfriend, “It’s going to be OK.”

The 16-year-old said to her father, “Dad, I’m OK.”

The last entry written in her diary said, “I’m just tired.”

***************

A pounding on the front door abruptly woke Richard Blackwell up Tuesday, Sept. 12 morning. Once he made his way to the door, there was a police officer on the other side asking him if he had a 16-year-old daughter.

The officer told the still-groggy father to check on his daughter.

Alex fell asleep the night before talking on the phone to her boyfriend. But her boyfriend knew there was something wrong.

When Richard went into her bedroom, Alex wasn’t breathing. She had no pulse.

Her mom instinctively started CPR on her, just minutes before the paramedics arrived and started to save her life. They whisked her out the door and to Emory Hospital’s emergency room.

For the longest two hours of Richard’s life, nurses and doctors did all they could to bring his daughter back to life. When one would run out of steam performing compressions on her chest, another would jump in and begin the life-saving efforts.

They pushed and pushed and pushed.

Alex’s heart would beat. And then stop.

Everyone was exhausted, but they tried one more time to bring her back.

But, she was gone.

Her family sat in the hospital, next to Alex’s bed in the emergency room, where she breathed her last breath.

They held her hand.

They kissed her cheeks.

They sat, crying, unable to leave her side.

Alex had been dealing with social anxiety and general depression since she suffered a concussion last fall playing soccer, Richard said.

“But we felt things were moving in the right direction,” he said in a blog post this week.

In fact, she had fallen in love with her best friend and it was the happiest her family had seen her in a long time.

“Suicide had been something that Alex said she considered in the past and we took that very seriously, but she was telling her therapist and us she was past that now and we were believing her,” her father wrote.

According to the Center for Disease Control’s most recent suicide report, in 2015, there were 1,537 suicides among males and 524 among females aged 15–19 years nationwide.

To date, 29 children, under the age of 18, have taken their own lives this year in Georgia, according to the Georgia Bureau of Investigation’s Child Fatality Review Unit (GCFR). A 61 percent increase since May, when the state had 18 suicides.

According to the GCFR, in 2016, there were 35 youth suicides, which was down from 2015’s 51, but up from 2014.

Psychiatrist Dr. Michael Rosen cringes at those numbers.

“Suicide is not a reasonable answer. It is by definition an illness,” he said. “Kids today are under so much stress then our kids were 10 years ago, 20 years ago.”

And one of the biggest concerns, he said, is that there is not enough help for them in Georgia, he said. Not enough hospitals. And he called mental health care in the state “horrendous.”

“There's absolutely not enough help. This is the crisis that we're in in Georgia. [We] lack access to good care,” he said. “But nobody is paying attention. Mental health is the poor, step-child… it's worse than Cinderella, in Georgia and in the country. We have a crisis.”

Richard, who is in the middle of that crisis, took to his computer and posted online his favorite photo of Alex when she was younger, alongside words, in which he poured out his emotion.

The grieving father wants all parents to know a few things that could save their own child from a self-inflicted fate like his daughter’s.

- If love could not save her what could? In my heart, I think Alex made one bad decision on one bad day. One impulsive decision that couldn't be taken back. Depression is curable. It just takes time.

- Sports concussions on children are worse than we believe. We need to stop Headers in Soccer and add more head protection in all sports.

- Girls can be very mean to each other. We can’t just talk about bullies; we parents must ensure that our kid shares warmth not hate to those they don’t like.

- The T.V. show, “13 Reasons Why” is great if you are not contemplating ending your life. For those in danger, it glorifies suicide and makes it seem not so hard to do.

- Don’t believe it when your daughter says, “I’m OK.” Check on her often if she is a risk. Share how important it is to just hang in there and get past the teens. Get her into therapy.

- Stop stressing your daughters about school and grades. Just stop.

- With depression, you are closer to the edge than you know. One bad day could be enough with an impulsive teen.

- Watch nutrition and get her exercise.

- Share this with parents, coaches and therapist you may know.

“The most difficult thing I have to treat are the parents of children who have committed suicide,” Rosen said. “If one parent out there sees this and engages in more conversation and realizes, ‘Gosh, my kid… something’s not right.’ [Richard] may have saved a life or two or five.”

Furthermore, Rosen said, after reading the father’s blog post, it’s not about how much her family loved her.

“It isn’t necessary an issue of whether they feel that their parents love them.”

High school life and adolescence is full of bumps along the way and teenagers don’t always see them coming until it’s too late, he said.

“They don’t know that their environment is going to change. That it’s not going to be a toxic bullying environment. They get off to college and they get off to a work environment.”

“Kids can be very mean to each other. Teens can be very mean to each other—girls in particular. Cyberbullying is horrendous,” he continued.

His advice to parents is much like Richard’s.

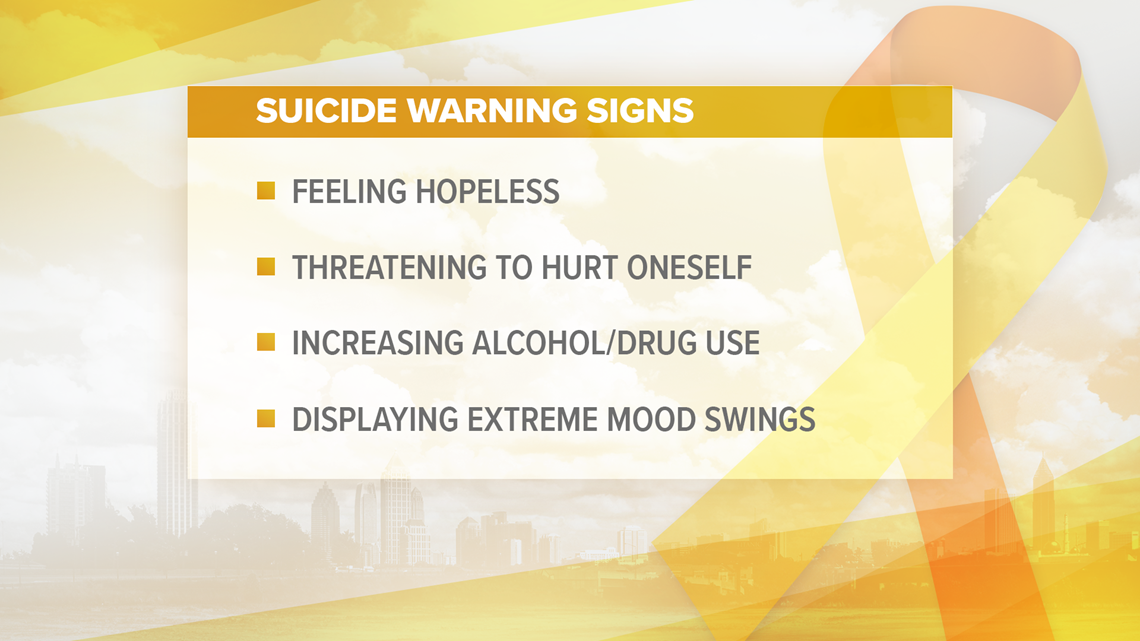

“If you see a pattern of change, if you see behavioral changes, if you see grades fall, if you see a child pulling back, being more isolative in socializing, these are concerning.”

Richard is asking anyone interested in donating in memory of Alex, to visit, http://www.soccerstreets.org/, an organization and community she was close to before she died.

Saving Georgia's children

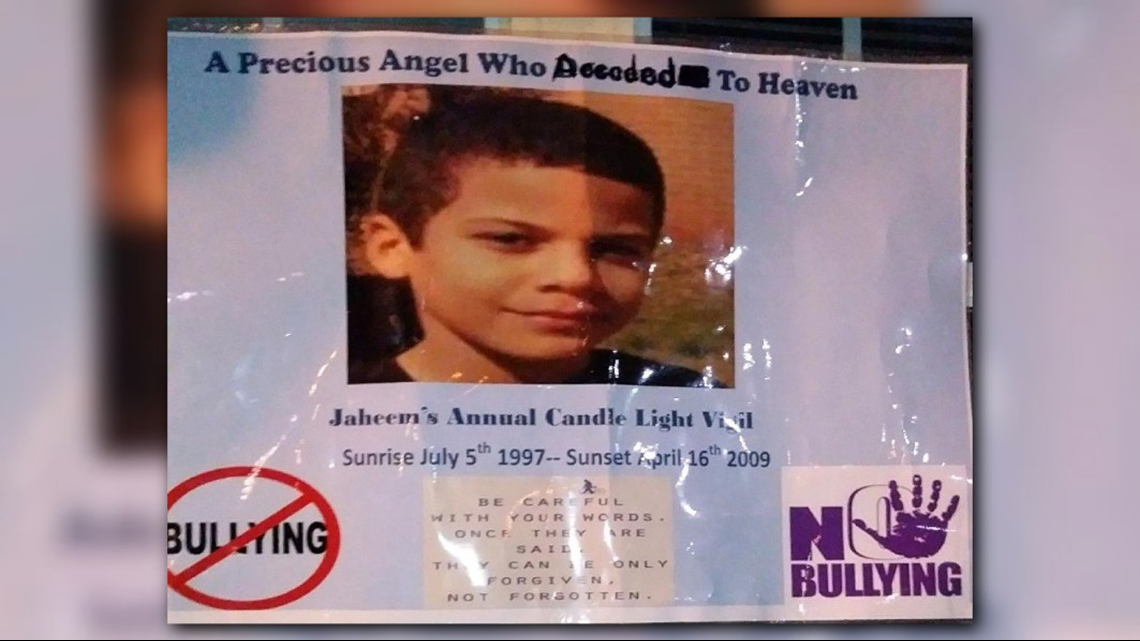

Masika Bermudez’s 11-year-old son was named student of the month on April 16, 2010—that night he committed suicide.

In the past two months, more than a dozen kids have killed themselves in Georgia. And while the bulk of suicides through 2015 have been ages 15-17, the number of 10-14-year-olds killing themselves is on the rise, according to the Georgia Bureau of Investigation’s Child Fatality Review Unit (GCFR).

To date, 18 children have taken their own lives in 2017.

Many of the suicides were carried out with guns, per the GBI’s data, with hangings as the second most popular method.

Bermudez knows.

She moved her son to Atlanta from St. Croix.

From the beginning, she said, he was bullied relentlessly in school. She read his journal following his death. He had documented page after page of torture. And each entry was worse and worse.

It had changed him.

“He wasn't the same active little boy who used to play and run and play with the sisters. He wasn't the same,” his mom remembered.

At first, he told her about the bullying at school, but eventually he grew silent.

“[I would] go to the school and they wouldn't do anything about it,” she said.

But on April 16, no one would be able to do anything about it ever again.

She remembers that day vividly.

“[I] went upstairs and I unlocked the door. Usually, [when] you open the door, you see the entrance to the closet. That day, I saw the whole closet—no doorway or nothing. Like it didn't have no walls. I just saw my son hanging there.”

“That's an image that's on mind forever.”

Trebor Randall, GBI special agent, wants families to talk about suicide in their homes with their kids.

“We cannot sugarcoat this subject. As sensitive as it is, as tragic as it is for a parent to lose a child, they don't want this to happen to another family,” she said.

Last month, Georgia had six children, under the age of 18, commit suicide.

“That was cause for concern,” Randall said. “Anytime one child takes their own life because they feel like they have no other option, that's alarming for us.”

The GBI recently took over the Georgia Child Fatality Review Unit and hopes to bring awareness to parents, children and schools.

“We're trying to be more proactive,” she said. “Suicide is at the top of our list as well because, we feel like in most cases if there is intervention early enough we may be able to save these kids.”

She hopes to equip parents, teachers and peers of the students on how to better deal with the crisis; how to better deal with stress; how to better deal with their peer-to-peer interactions; so that they better understand and know the warning signs.

“Just like, they talk about a village is needed to raise a child, it takes a village to save a child,” she said. “It’s important to listen to your kids, turn off the TV.”

If parents can teach their children coping skills; teach them that it’s not the end of the world, Randall said, maybe they can also talk to them about their emotions. And listen with empathy. Even if it’s uncomfortable or feels like a sensitive topic, he said, talking is key.

“It’s never too sensitive to share with other parents and other individuals who care about the welfare and wellbeing of children,” he said.

It's what the GBI likes to call, "saving Georgia's children."

“You know, if we could save one, but we don't want to stop there,” Randall said. “We want to saturate the state with this message.”

Psychiatrist Dr. Michael Rosen said that Bermudez’s son isn’t alone. Far from it. In fact, he said there is a mental health crisis in Georgia. And it continues to affect younger and younger children.

“There is no question that, just anecdotally speaking, we are seeing a rise in the number of cases of people that are having thoughts of suicide or attempting suicide,” Rosen said, especially with high-achieving kids.

“The kids are pushing and pushing… taking the hardest possible curriculum they can possibly take and then they're involved into sports and extracurricular activity they're not getting to bed until 12:30, 1 in the morning, they're getting back up at 5:30, 6 in the morning.”

They are getting four or five hours of sleep at best. They should be resting for nine, Rosen said.

“They’re like a hamster on a wheel, and they feel like there's no end in sight, so they are chugging and chugging and pressing to get to college and when they get to college and press to make the best grade, to get to the next level.”

But, he said, there is no end in sight for these kids and that's what happening.

“They're starting to feel helpless, they are starting to feel hopeless and that's what leads to suicide—they don’t have life experience to deal with it.”

And there’s no help for them in Georgia, he said. Not enough hospitals. And he called mental health care in the state “horrendous.”

“There's absolutely not enough help. This is the crisis that we're in in Georgia. [We] lack access to good care,” he said. “But nobody is paying attention. Mental health is the poor, step-child… it's worse than Cinderella, in Georgia and in the country. We have a crisis.”

According to the GCFR, in 2015, there were 35 youth suicides--16 of those were between 5-14 years old. This year, 10 children have killed themselves with guns, six have hanged themselves and two have overdosed. Ten of those suicides were white males.

Schools, he said, are not doing their jobs to address bullying issues, nor are they paying attention to what's going on because he is starting to see younger and younger kids who are being bullied, and who are having suicidal thoughts.

“Yesterday, I had a 10-year-old who was in here saying that about three or four years you tried to hang himself,” he said. “There's hope but we have to do a better job.”

Now, Bermudez holds an annual candlelight vigil every year. It’s something that she said helped her get through her own grief and she hopes that it helps others dealing with the same pain.

“I've learned how to cope with it,” she said about losing her son who would have turned 20 this July. “At first it was a real, like, that was my only son.”

“I just asked God to one day give me some closure, but I don't know if that's going to happen,” Bermudez said, who said that her advocacy for so if I prevention led to an anti-bullying act getting passed in the Georgia legislature.

She said that she wants kids to know that they need to keep the topic out there and the discussion loud.

Don’t stay silent, she urged.

“Not under the rug. That's what they tried to do with my son, sweep it under the rug and move on,” she said. “Speak out; speak out. Don't keep it in.”

And to parents, she urged them to ask your child questions.

“How is school?”

“How is everybody treating you?”

“Is everything going all right?”

And while she fights and speaks out on the topic for other parents and children, so that no more are lost to suicide, she still wonders what might have been with her own son.

“Oh my God, he was so handsome. I don't know. I don't know. But I just wish you was here.”

Meghan Frick, with the Georgia Department of Education (GaDOE), said that school-aged suicide is on the rise. In 2015-16, 9 percent of students said they had seriously considered attempting suicide in the past 12 months; 4 percent said they attempted suicide in the past 12 months.

Reversing this trend is a top priority for the GaDOE, Frick said.

In fact, GaDOE, the Georgia Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities (DBHDD), the Georgia Bureau of Investigation (GBI)’s Child Fatality Review Program, the Georgia American Academy of Pediatrics, Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, Georgia State University and Mercer University came together to form a Suicide Prevention Task Force.

Together conducted a series of Suicide Prevention Summits for school personnel last spring.

The sessions took place in Macon, Rome, Gainesville and in Gwinnett County—each had had suicides of children under 18 years old reported for three years in a row. More than 200 teachers and school employees were trained in suicide prevention, given child death data including youth suicide stats, and given resources and tops on how to deal with a suicide in their schools.

“It is unimaginable for even one child suicide to take place,” State School superintendent, Richard Woods, said. “We’re working with experts from across Georgia agencies to make sure every child can turn to their school for help – and to make sure every school has the resources they need to provide those supports for students.”

Strategies focused on a proactive approach, rather than reactive, and ensuring every school has the resources it needs to address the issue of youth suicide—giving all children access to those resources.

“We want it to never be the case--that a child cried out for help and no one listened,” Shevon Jones, a child fatality prevention specialist with the GBI, who worked with the schools, said.

'Hero' officer saves woman from jumping off overpass

An Atlanta Police officer was saluted as a hero for successfully talking a woman out of jumping from an overpass off Interstate 20 on Oct. 16.

“I heard a suicide call and I’ve had a success in the past and decided let me go over to Moreland and I-20 to offer my assistance,” Officer Lisa McGhaw said.

McGhaw said she saw a woman on the ledge, "and immediately just jumped in and offered my assistance.”

“I made a conscious decision to go over the ledge," McGhaw said. "She was apprehensive at first but after a while of speaking with her, I was able to close enough with her and attempt to build a rapport.”

McGhaw is trained in Crisis Intervention Training, also known as CIT training. The training focuses on de-escalation techniques such as listening and being patient when dealing with people with mental health issues.

“It was clear to me that she was desperate,” McGhaw said.

The patrol officer spent an hour on the ledge talking and listening to the woman.

“The ledge did not intimidate me,” McGhaw said. “The sole thought process was to get her to safety.”

She and the woman reached a breakthrough and developed an exit strategy together, standing up together when SWAT members pulled the woman back over the ledge, she recalled.

“I’m not a hero. I’m just a patrol officer with the city of Atlanta doing my job as required. I just happen to feel that my presence was needed at the scene at that time.”

Yet, the officer credits her CIT training for equipping her with skills she needed to help those in need.

“When I first came on, we did not have (CIT training] but after years and years of lobbying for mental health, the city of Atlanta decided to go ahead and make it mandatory for us to take that training,” she said.

“I’ve used those CIT training skills several times before, and have had plenty of successes," McGhaw said. “I’m very grateful I had those tools at the time.”

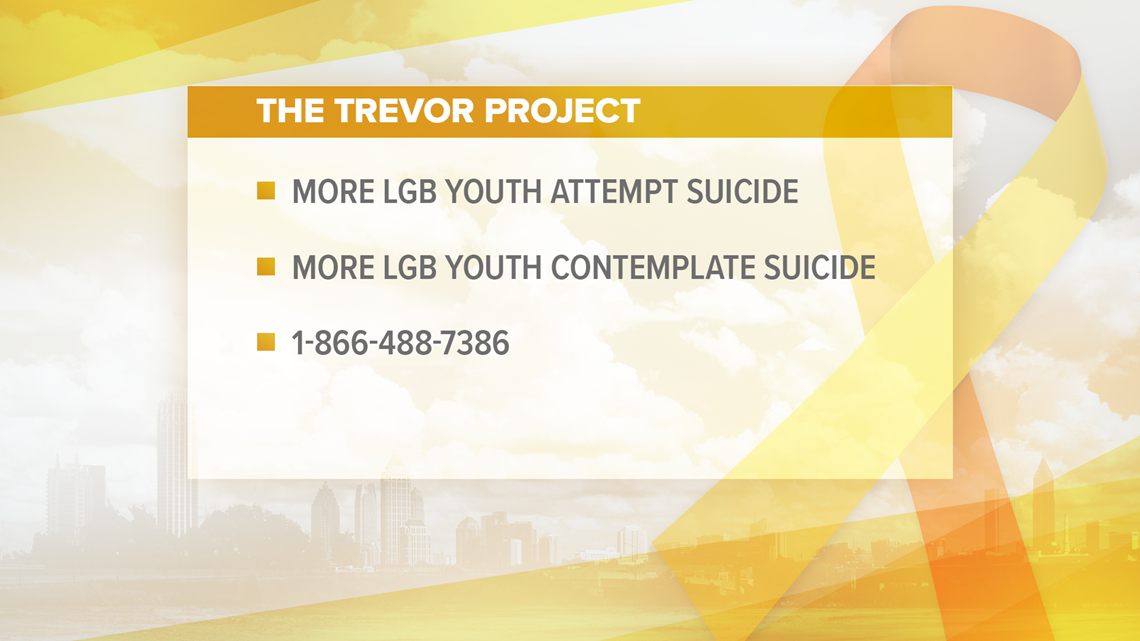

The Trevor Project

The Trevor Project is the leading national organization providing crisis intervention and suicide prevention services to lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and questioning young people ages 13-24.

The most recent CDC statistics show nearly 1/3 of LGB youth had attempted suicide at least once in the prior year compared to 6 percent of heterosexual youth.

LGB youth contemplate suicide at almost three times the rate of their peers. The Trevor Project has its own hotline called the Lifeline, and it's available 24/7 for calls or text.

Help someone you know

Out of the Darkness

In an effort raise money and awareness, The American Foundation for Suicide

Prevention is

holding a Out of the Darkness walk on Sunday, Nov. 5 at Piedmont Park at 2 p.m.11Alive's Liza Lucas, Neima Abdulahi and Faith Abubey contributed to this story.