ATLANTA — The article poses a provocative question – “What does a traffic jam in Atlanta have to do with segregation?” and offers a provocative answer: “Quite a lot.”

It was published in The New York Times on Wednesday, part of a series called the “1619 Project,” which is examining the lingering impacts of slavery 400 years after European colonists first brought it to America.

Atlanta is widely acknowledged as having some of the worst traffic in the country.

That has to do with everything from the city’s inefficient layout to its maligned public transportation system to simply being full of bad drivers.

But many of the infrastructure issues that plague the city in fact trace their origins to segregation, the author of The Times article, Princeton historian and author Kevin M. Kruse, told 11Alive.

“We have to remember that the rise of the modern expressway movement, the interstate highways in the 50s, is really obviously a postwar transformation that hit American cities at the same time a lot of them are wrestling with issues of segregation,” Kruse said. “Especially in the South.”

Kruse said the planning for the interstates in Atlanta became a double-edged sword: being used both as an excuse to build through and tear down black neighborhoods and then serving as a de facto border between the white and black neighborhoods once built.

One of the most infamous examples involves Interstate 20.

A 1960 Atlanta city planning report openly said the layout of I-20 west of downtown “would be the boundary between the White and Negro communities.”

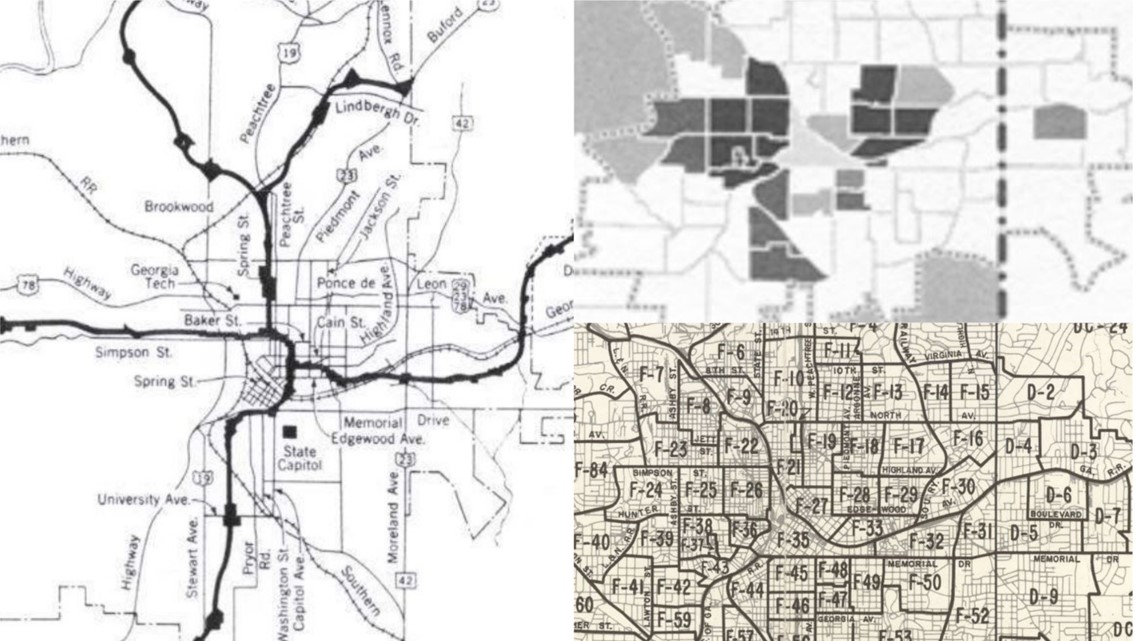

A 1947 map shows the planned route for the metro Atlanta expressway system to run along Simpson St. west of downtown, right above the areas of the city with the most black residents, as seen in a 1940 Census map compiled by Kruse.

A 2007 Georgia Department of Transportation history of the interstate highway system in the state characterizes the Lochner Plan as responsible for the “network’s most problematic feature – the section through downtown Atlanta that connects four of the six radiating routes.”

While the Lochner plan was based on earlier maps for the extending routes out of downtown that followed the “existing regional railroad network plan” and the “historic transportation patterns laid down in the railroad era” the 2007 document notes how specific considerations were made for laying out the roads to separate certain sections of the city.

“To the greatest extent possible, the routes were intended to go through ‘marginal neighborhoods’ … such layouts reflected the thinking of most urban road builders, and many planners as well, since marrying road construction and ‘slum clearance’ (later named urban renewal) offered the best chance of minimizing property acquisition costs for the new highways.”

This targeting of poorer neighborhoods was one of Kruse’s central premises, he said.

“A lot of these roads are routed through what would have been old-standing black neighborhoods, not just in Atlanta but across the country – and they destroy a lot of those areas,” he told 11Alive. “This dovetails with the process of urban renewal, which is a bit the same thing – they targeted downtown slum areas, as they were known, and really obliterated black neighborhoods.”

“The saying goes, popularized by the novelist James Baldwin, that ‘urban renewal really means Negro removal,’” Kruse added.

As the Civil Rights Movement progressed, the way segregation and mass transportation went hand-in-hand evolved, Kruse said.

The flashpoint was MARTA.

“So here’s an instance where, again, the transportation innovation coincided with a new stage in the Civil Rights struggle across the country. And so when MARTA really pops in Atlanta, it’s in the mid-60s to early-70s, at the peak moment of white flight out of Atlanta,” he said.

Whites moving out of the city, Kruse said, were trying to flee what they saw as the creeping ills of urban poverty and proximity to African-Americans.

“So they just draw the line at this and they don’t want it at all, and so these counties overwhelmingly reject – Cobb and Gwinnett overwhelmingly reject MARTA when it comes up for votes in the 60s and early 70s,” he said. “And are still resistant of course to it today.”

The latest MARTA vote in Gwinnett County, its first in nearly 30 years, failed in March.

Kruse’s piece in The Times offered a quote from a former Republican legislator after the last Gwinnett MARTA failure, in 1990: “They will come up with 12 different ways of saying they are not racist in public. But you get them alone, behind a closed door, and you see this old blatant racism that we have had here for quite some time.”

MORE HEADLINES: