ATLANTA — Almost two centuries of American history line the walls at the Georgia State Capitol. Portraits honoring past leaders offer a glimpse into the state's history and how Georgians in the past choose to honor them.

Within the almost 300 portraits, sculptures, and other memorials that make up the capitol art collection, the stories of three prominent Native Americans are on display.

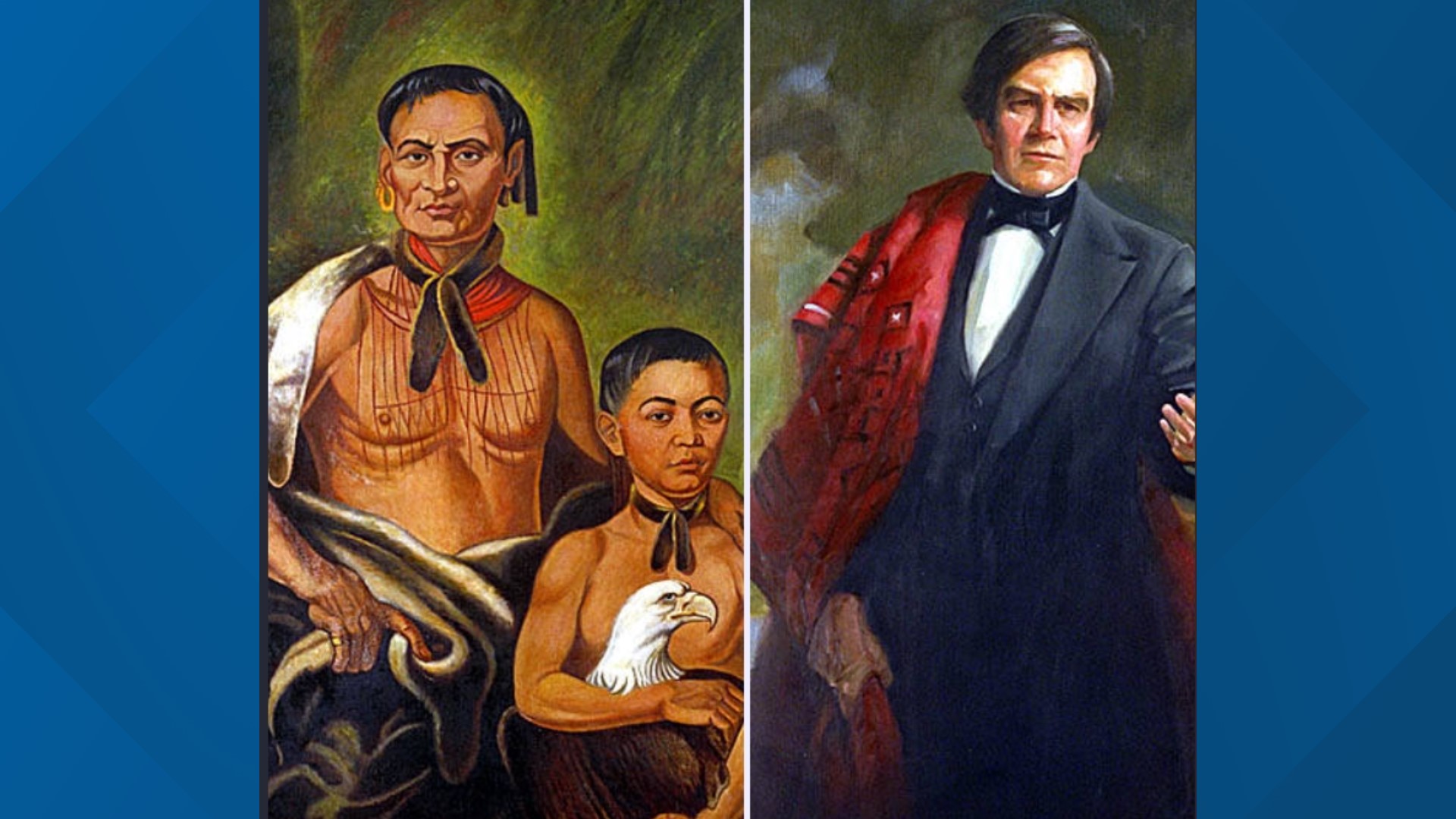

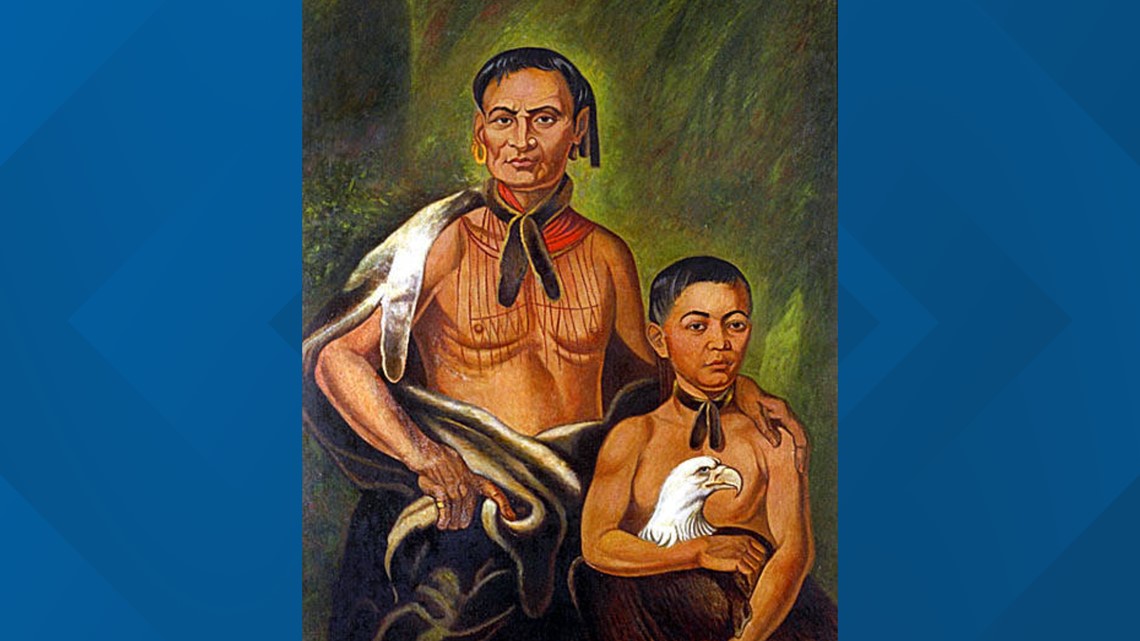

Tomochichi and his nephew Toonahowi

Two portraits are featured inside the office of Georgia's state manager, the governor's office.

"Behind me is a portrait of Tomochichi and his nephew Toonahowi. Tomochichi was the leader and founder of the Yamacraw tribe, who were located where Savannah currently is," said Sophia Queen, manager of tours and education at the Georgia Capitol Museum.

Queen, who gives the tours at the Capitol tells said children's eyes light up once they see the portraits.

“I see on a daily basis the way that it changes a kid's experience of the building," Queen said. "It makes it less intimidating for them to see people that look like them. It makes them feel more welcome to see themselves represented here.”

Tomochichi was a prominent figure in early Georgia history and the leader of the Yamacraw.

First led by Tomochichi and then by his nephew Toonahowi, the Yamacraw were made up of about 200 people and consisted of a mix of Lower Creek and Yamasees, according to The New Georgia Encyclopedia.

Tomochichi's group settled near the Savannah River and during the first five years of British settlement, he became the negotiator between British settlers and the Creek.

He would accompany military leader General James Oglethorpe on a trip to England as a cultural representative and meet with important British dignitaries.

Tomochichi pushed for recognition and realization of the demands of his people for education and fair trade, according to the New Georgia Encyclopedia.

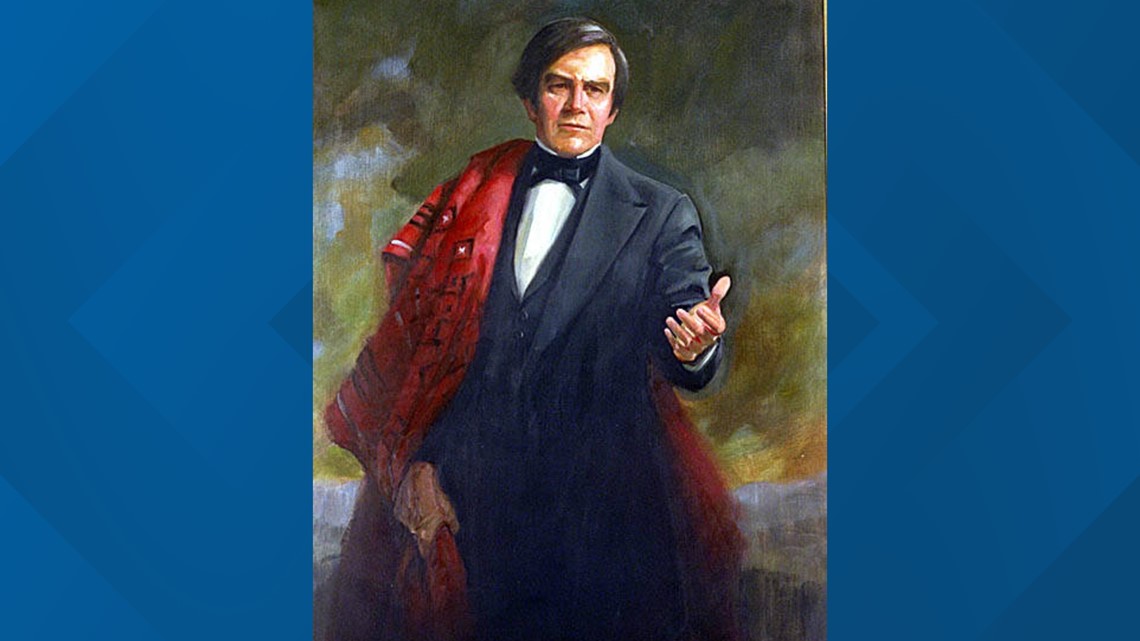

John Ross

On the third floor, the portrait of prominent Native American leader John Ross hangs.

"John Ross was the principal chief of the Cherokee Nation during the time it underwent the Trail of Tears," said Queen.

Ross served as Principal Chief for nearly 40 years and supervised the 800-mile journey.

As a strong advocate for the Cherokee, Ross refused to let the U.S. government take their land for new settlers.

During his efforts to stop the land from being stolen, Ross would often travel to Washington, D.C, to speak on behalf of the nation.

Despite his efforts, other Cherokee leaders signed the Treaty of New Echota in 1835, and in 1838, the Cherokee were forced to leave their homes and move to Oklahoma.

All survivors of the Trail of Tears arrived west by 1839. According to the National Park Service, no one knows the exact number of how many who died throughout the journey west. It is estimated that 3,500 people died, nearly a fifth of the Cherokee population.

According to information from the Tennessee State Museum, the loss experienced by the Cherokee people did not deter Ross from helping.

Once in Oklahoma, he helped build a new capital city called Tahlequah, schools and other buildings.

Ross served as the Principal Chief of the Cherokee Indians until his death in 1866.

This story is part of a series of stories done by 11Alive's Dawn White for Native American Heritage Month.