More than half of Tampa's 2022 homicides remain unsolved: Investigators say silence keeps the killers free

"You’re so close to making an arrest on it, but you just need that witness...to come forward," TPD Sgt. Mike Lippold said.

In 2022, there were 46 homicides in the city of Tampa. More than half are unsolved. Police say their biggest hurdle is getting witnesses to cooperate.

But fear of retaliation and the “no snitching” code often keeps people silent. State funding for programs to protect witnesses no longer exists. Grieving families are left to suffer when detectives can’t close cases.

We cover these crimes when they occur, but there's a story about what happens after the camera stops.

As the nation prepares to mark gun violence awareness day on June 2, 10 Tampa Bay and our TEGNA sister stations across the country are investigating shootings from this week last year — and showing the impact these crimes still have today.

In Tampa, there were three shootings that resulted in two deaths. Getting anyone in the community to talk was a challenge. Police say it’s why most homicides in the city remain unsolved.

Still searching Grad party-turned crime scene

The late-night party that spilled over into the early morning hours of May 29, 2022, was supposed to be a graduation celebration.

Gunfire turned it into a crime scene.

Tampa police say a gunman drove by and shot into a group of people on East North Bay Avenue near 34th Street, striking Antonio Richardson and one other person.

One year later, there are hardly any leads in the case.

No one will come forward. No one will talk on-camera. Richardson’s killer remains on the loose although neighbors believe someone knows who did it.

It's a common theme for homicide investigators in Tampa, who say they when they struggle to close a case, it's usually because witnesses choose to remain silent.

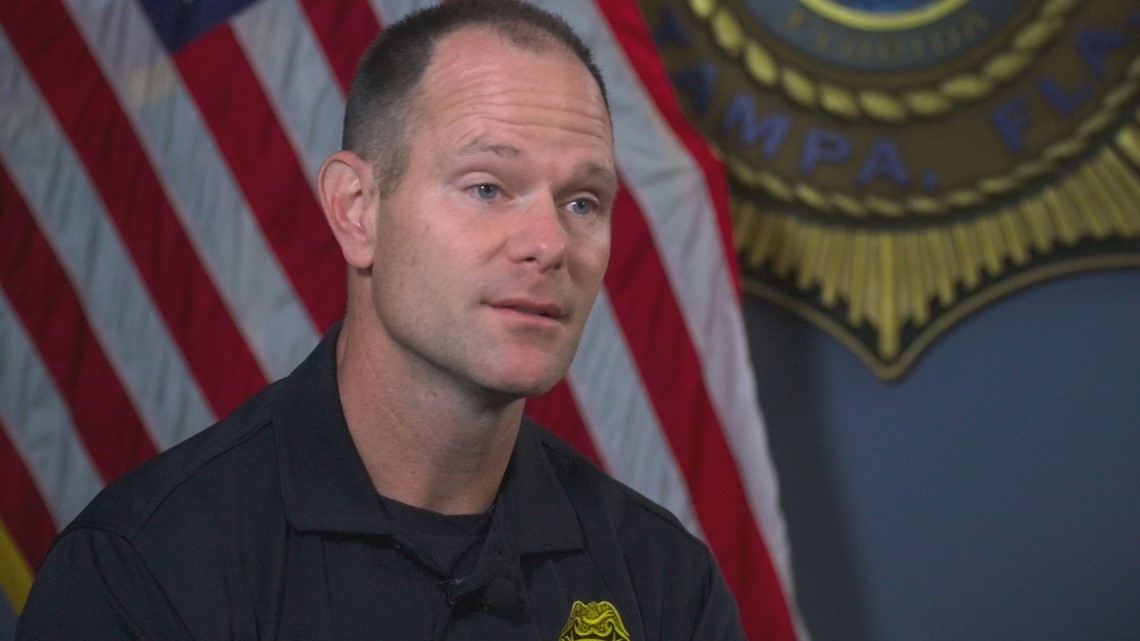

“It just wears on you,” said Sgt. Mike Lippold of the Tampa Police Department’s homicide squad.

“I’ve had many nights where I just can’t sleep, or I end up waking up thinking about a case because…you’re so close to making an arrest on it, but you just need that witness, you know, to come forward,” Lippold said.

A mother's hope “I’ve prayed about it day after day.”

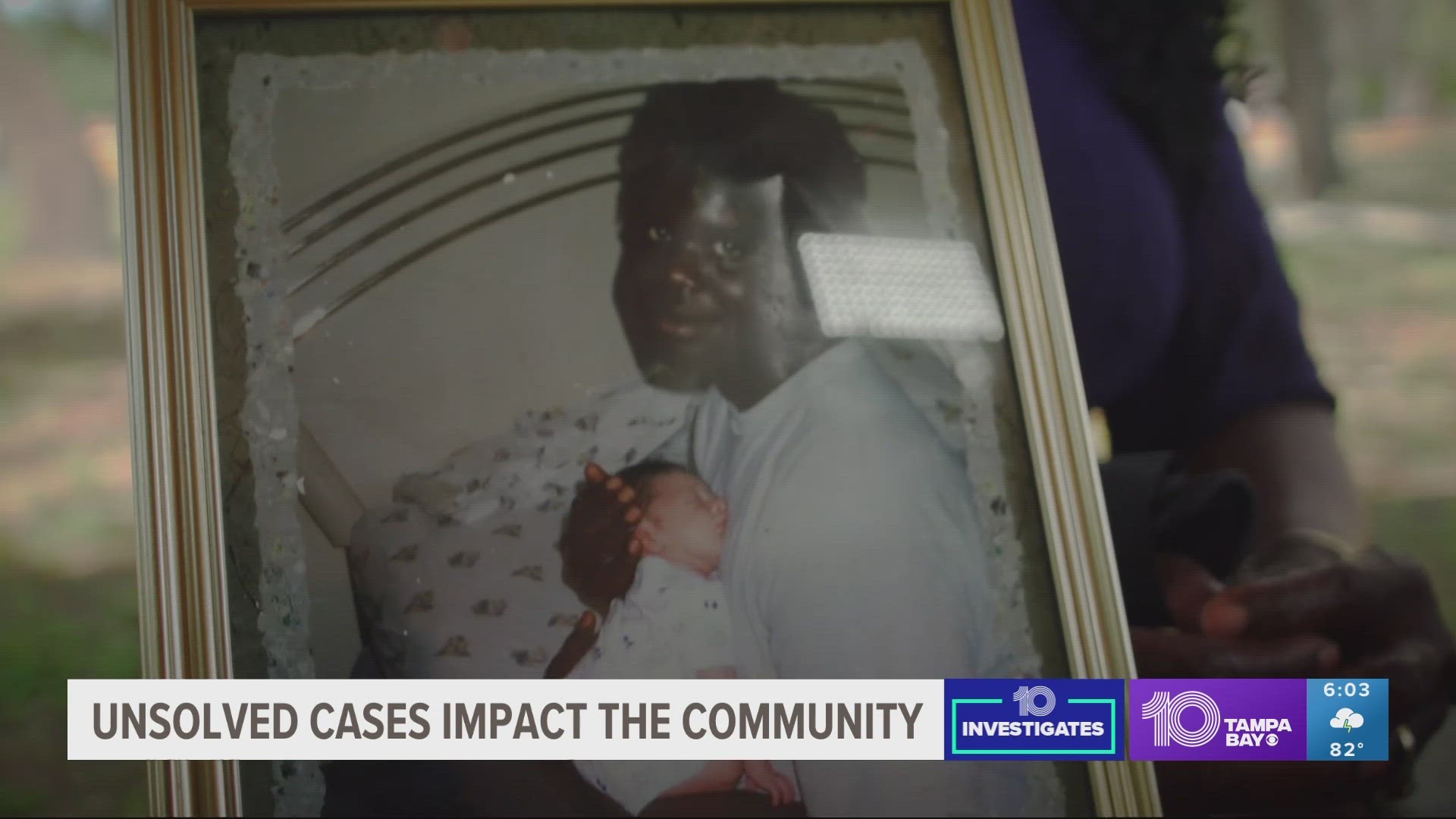

Darla Saunders understands the pain the Richardson family must feel. Her son, Isaiah Brooks, was murdered in Tampa in 2005. No one was ever arrested in his case.

“It was just the most horrific thing I have ever experienced,” she said.

Saunders says her son had received a settlement from a car crash, and people in the neighborhood knew about the money. She believes someone wanting some of his cash might be connected to his murder.

“Why would somebody take my son's life? Why? Who would be so horrible or so evil that would take a life?” Saunders said. “Isaiah was like a big ole teddy bear. A big ole tall teddy bear. Six-foot-seven, 250 pounds.”

Like Richardson’s case, Saunders believes someone knows the killer, but won’t come forward.

“As [neighbors] were trying to provide answers to me, I even saw one of the houses get their door kicked in,” Saunders said. “And they were intimidated and told that they better not say anything. And one neighbor had to move their child out of the city of Tampa for a year because she was so afraid to be there.”

“I’ve prayed about it day after day, just waiting for God to let the answer come through so that we can get some closure, some peace and have justice served,” she said.

Culture of quiet Why some witnesses refuse to cooperate

Lippold says the most difficult part of solving homicides in the city is the lack of witness cooperation.

“Every single case,” he said. “I think some is out of fear…obviously retaliation. I think some is—it could be trust with law enforcement, unfortunately.”

Dr. Richard Moule, Jr., an associate professor of criminology at the University of South Florida, says this is common in Black communities.

“This is most prominent in communities of color that have had long-standing and often acrimonious relationships with law enforcement,” he said.

Moule points to the 1968 Kerner Commission report for historical reference. The report came out of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders. It sought to explain the root causes of riots that swept cities across the nation, including Tampa, in 1967.

The report cites strained police relationships in Black communities as one contributing factor. In Tampa, riots broke out after a TPD officer shot an unarmed teenager as he was running away from a suspected burglary. Moule says the strain from these types of incidents is still present in many communities today.

"When individuals in these communities don’t trust the police, and they don’t feel protected the police, then they don’t feel safe,” Moule said. “They’re unwilling to engage the police. They’re less willing to call them when they need help. They’re less willing to serve as witnesses or testify at trial. They’re less willing to come forward when they are victims of crime.”

It's a nationwide problem leading to more killers getting away with their crimes.

Data from the FBI shows in 1965, the national homicide clearance rate was 91 percent. In 2020, that number dropped to 54 percent, which is about the same rate for Tampa.

“We have several [homicides] in the last couple of years where there are probably 50 people plus at a certain area and a shooting occurs,” Lippold said. “Someone is obviously shot and dies and no one communicates. Or some people do, but they give a general description of a suspect. Or at times someone might even give a suspect, but are not willing to go on record to testify against the suspect.”

Protecting witnesses State funding eliminated

TPD does not have an official witness protection program, but Lippold says the department has relocated people when necessary.

“I know in the past, we’ve moved people. We do the best to try to keep information confidential,” he said. “But unfortunately, like I said, everything can’t be confidential.”

Local police departments are eligible under certain circumstances to receive state funding for relocations from the Florida Violent Crime and Drug Control Council.

Its 2022 annual report shows that the council spent $13,600 for three victim/witness protection and relocation reimbursements for the last part of the 2021-22 fiscal year.

The program depends on funding authorization from the legislature, but information from the Florida Department of Law Enforcement shows funding is not currently available for the current year.

“Unfortunately, a lot of people don’t have the ability to simply uproot and leave,” Moule said. “And so, I think for many of them, they feel that the safest route is staying quiet trying to keep their head down and hoping it goes away.”

For mothers like Saunders, it never does.

“Losing a child, period, has been the worst thing I believe that has ever happened to me,” she said.

Yet, nearly 20 years later, she’s still optimistic that someone will break the silence for her son, for others like Richardson and for the entire community.

“I haven’t given up hope that we will find answers,” Saunders said. “I feel that the answers are there. I feel that we already know. I just want people to do the right thing and go ahead and solve the case.”

Editor’s note: The voter-approved Marsy’s Law prevented 10 Tampa Bay from getting records and information associated with shootings we wanted to track from this week last year. The law shields certain records that were once public, making it more difficult to report details of what is happening in your community.

Emerald Morrow is an investigative reporter with 10 Tampa Bay. Like her on Facebook and follow her on Twitter. You can also email her at emorrow@10tampabay.com.