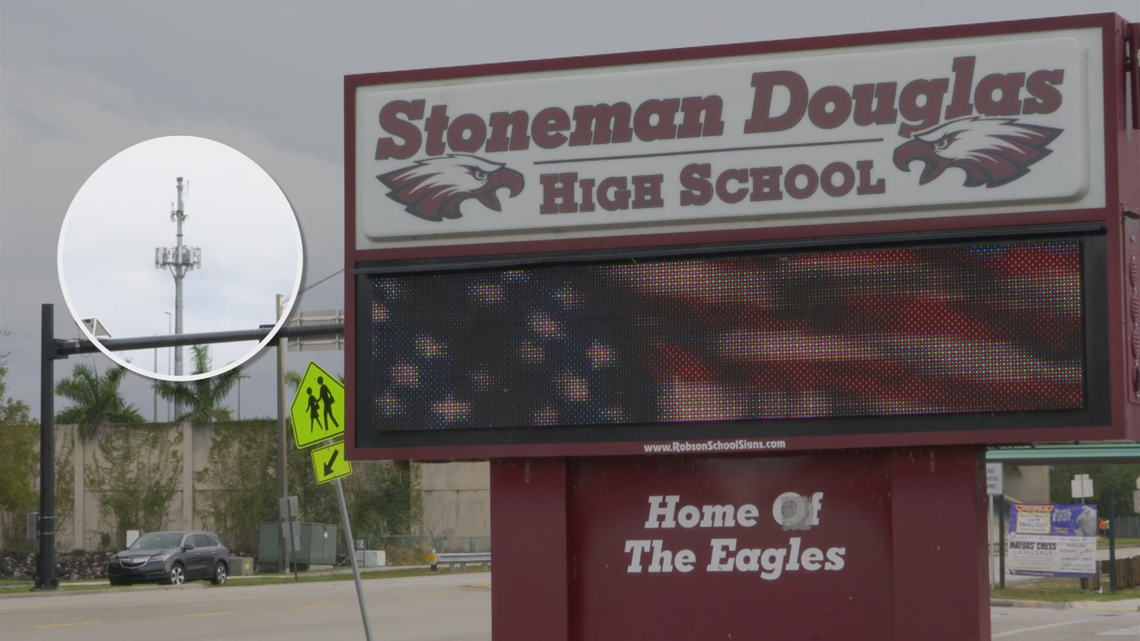

PARKLAND, Fla. — A cell tower stands in the middle of a city park, just across the street from the high school where 34 people were shot one year ago.

The cell tower is not in Parkland, but Coral Springs.

Every single 911 call from Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School on February 14, 2018 went to Coral Springs Police. But Coral Springs does not provide police services to Parkland, and dispatchers transferred multiple calls for help to Broward County 911.

Only one caller was still on the line after the transfer.

The very first call from the high school was received at 2:22:13 p.m. while Nikolas Cruz was shooting his first victims. The caller, a female student, was incredibly calm under fire.

“Hello, we’re at Stoneman Douglas High School, and I think there’s a shooter…”

In under three seconds, the student told the dispatcher what was happening and where to send help. Her sentence was cut-off by the sound of gunfire, confirming what she had just said.

Then she hung up.

The Coral Springs dispatcher did not send police. Instead, he called Broward County 911 and spent a full minute trying to explain what he had heard, before the Broward dispatcher realized she was talking with another dispatcher in a different 911 center.

WATCH | The Reveal airs Sundays at 6 p.m. on 11Alive

According to the Marjory Stoneman Douglas Commission Report, 69 seconds elapsed between the first 911 call and the time the first police officer was dispatched to the school.

By that time, the gunman had already shot all 24 victims on the first floor, and was headed upstairs to shoot more.

17 students and teachers lost their lives that horrific February day.

911: Lost On The Line

We first revealed stunning weaknesses in our 911 systems four years ago, three full years before the school shooting in Florida.

Our two-year, 14-part investigation began with the death of Shanell Anderson in Cherokee County. She accidentally drove her SUV into a retention pond in December 2014, and spent her last breaths telling a 911 dispatcher exactly where she was.

Rescuers found the pond after 20 minutes of searching, and pulled her from the fully-submerged vehicle. Shanell died in a hospital a few days later.

PREVIOUS | 911 couldn't find her. She died.

Our investigation revealed three critical failures that killed Shanell. First, her call reached the wrong dispatch center, because wireless 911 calls are routed by the cell tower location, and the nearest tower was across the county line. Second, the specialized maps Alpharetta-Milton 911 was using stopped at the county line, so her location would not plot on the dispatcher’s screen. The third problem was the Shanell’s cell phone could not be located by the 911 center in time to save her life.

A year later, George Treadaway drowned in a strikingly-similar incident in Gordon County. He was trapped in his car, surrounded by rising flood waters, and spent his last seconds of life trying to tell 911 dispatchers where to find him.

As a result of our investigation, Alpharetta and other jurisdictions expanded their maps, inventors developed a patented tool to help trapped drivers escape from sinking cars, and a team of innovators created an elegant solution for the cellular 911 location and routing problems.

In all, inventors inspired by our reporting have received seven patents. Meanwhile, Google and Apple have built their own systems to help 911 get more accurate location data.

We thought the problem was solved. Until we heard 911 calls like the ones from Parkland.

Parkland decided to send 911 calls to the next city – on purpose

All the callers in Parkland knew exactly where they were: Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School. So cellular location was not the problem.

Why then did all the 911 calls from the high school go to a 911 center that could not dispatch police?

Because Parkland city officials wanted it that way.

Parkland contracts with Coral Springs for firefighting and ambulance services. Under a separate agreement, made years ago, Broward County Sheriff’s deputies provide police services to Parkland.

In a fateful decision, Parkland decided to route all landline 911 calls to Broward’s dispatch center, but all cellular 911 calls to Coral Springs. Not only are 80 percent of 911 calls from cell phones these days, but every single 911 call from the high school during the shooting came from cell phones.

Not a single 911 call from Marjory Stoneman Douglas was made on a landline phone, so none of them were routed directly to the police department that protects the school.

The state commission wrote in its report, “this process required the caller to explain their emergency to the [Coral Springs Police] dispatcher and then repeat it to the [Broward County Sheriff] dispatcher after the transfer…many callers also become frustrated because they have to explain their emergency a second time and they do not understand the necessity of the redundancy.”

Max Schachter says the problem is one of public expectations. “They think that if you dial 911 you’re going to get the police and you’re going to come and help you,” Schachter said. “Nobody ever thinks you’re going to have to tell your story to one operator, then they’re going to have to transfer you to a different operator. It’s just ridiculous,” he added.

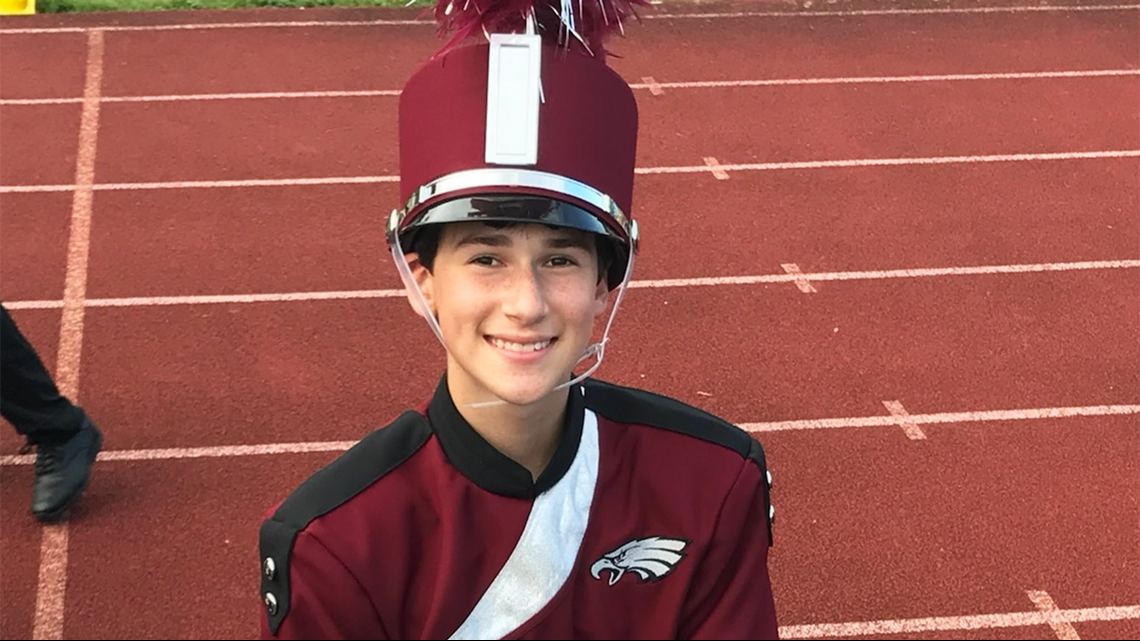

Schachter’s 14 year old son, Alex, was murdered in the Parkland school shooting.

Schachter also served on the Marjory Stoneman Douglas Public Safety Commission.

The official timelines shows Alex Schachter was shot and killed during that first transferred 911 call.

“That whole process took over a minute, and by then 24 people were shot or killed. So it wouldn’t have saved my little boy even if it had been a perfect scenario, because Alex was unfortunately the warning shot for the kids on the second floor to run and hide. Alex was one of the first little boys that was murdered,” Schachter said.

Schachter has started a foundation, Safe Schools For Alex to force schools to increase security. He proposes a ‘Alex rating’ that would allow parents to choose where to live based on the relative safety of the neighborhood school.

He also wants to see trackable key-fobs that teachers could wear, with a panic button that would immediately contact police.

“After 911, we fixed the airports,” Schachter said. “After the Oklahoma City bombing, we made the federal buildings safe. We developed fire codes in the United States to protect children from ding in a fire, and it’s worked. Kids haven’t died in a fire in a school in 60 years. And it’s been 20 years since Columbine, and kids and teachers continue to die in their classrooms. And so I set out on a mission to create this foundation called Safe Schools for Alex, and our mission is to make schools safe all over the country,” the father added.

The calls would have gone to the wrong 911 center anyway

The nearest cell tower to Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School is directly across the street – in Coral Springs. So, every 911 call made from the school on February 14, 2018 would have gone to Coral Springs anyway.

Four years after our national investigation and despite recent interest from the FCC to fix the routing problem, all wireless 911 calls and text messages in the U.S. are routed by the cell tower address, not the phone’s location.

“As soon as this problem was identified, I’ve been trying to fix this problem. Because if there’s another mass casualty incident tomorrow, we are still going to have to transfer these calls, and people are going to die because of it,” Schachter said.

911 center consolidation reduces transfers, increases confusion

One of the proposals from the Florida commission is to consolidate 911 centers as much as possible, even creating one massive 911 center for the whole state.

The idea is that the larger the 911 jurisdiction, the fewer the transfers. That is true, though 911 experts point out, “there’s always an edge, always a border.” Calls from Georgia and Alabama could be picked up by a statewide 911 center in Florida.

The only way to nearly eliminate transfers is to change the way 911 calls are routed.

Technology exists to use the phone’s location data – currently provided to cell phone companies by Google Android and Apple iPhone – to route the call to the correct jurisdiction within a few seconds. We’ll explore that fully as we continue to investigate the national 911 problems.

In the meantime, cities like Parkland have to come up with their own patches and methods to mitigate the transfer problem, such as the split between Coral Springs and Broward that contributed to an already-flawed response to the school shooting a year ago.

Broward County Communications is a consolidated 911 center already. Coral Springs was criticized for pulling out of the consolidation plan and running its own 911 center, but Coral Springs officials were reportedly not satisfied with the level of service the larger center could provide to its citizens.

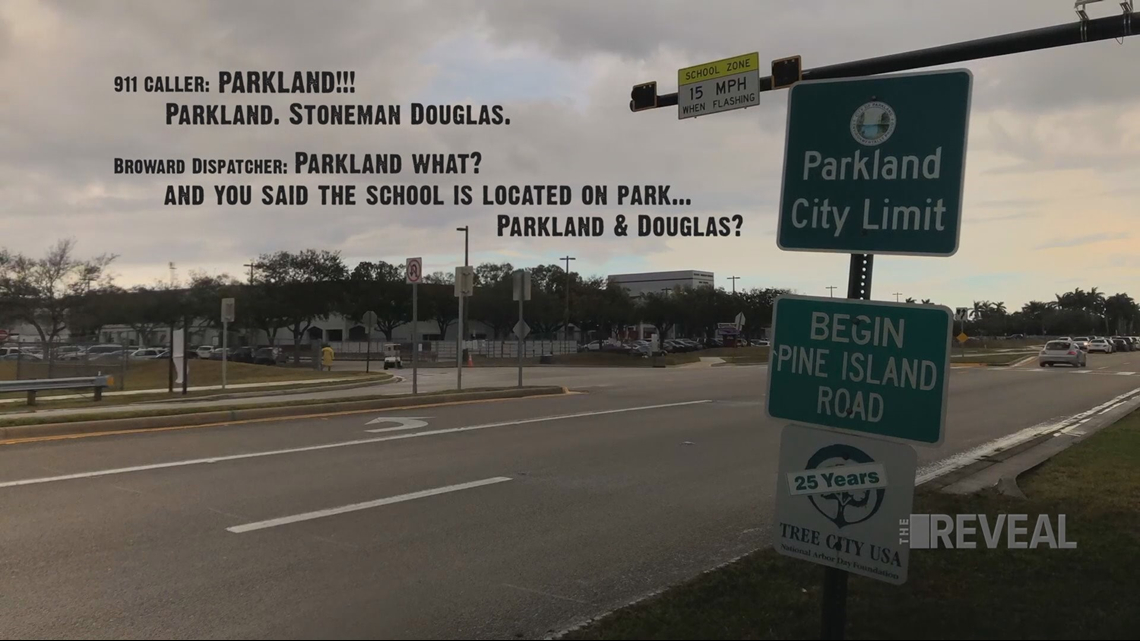

During several 911 calls on that fateful day, Broward 911 dispatchers seemed genuinely confused about the location of the school shooting, even though callers were telling them the precise name of the high school.

“OK, does anyone have an address to where I’m sending the police to?,” one Broward dispatcher asked her colleagues. While they were responding, the 911 caller exclaimed, exasperated, “you don’t have the address for the high school in Parkland?!!”

Two Broward dispatchers mistakenly believed the callers were giving them an intersection, not the name of the school. “Hi, I just got a call that there was a school shooting over at Stoneman Douglas,” a 911 caller said. The dispatcher replied, “Stonan and Douglas?”

On another 911 call, a man repeatedly said the location of the shooting was, “Parkland, Stoneman Douglas!” The Broward dispatcher responded, “And you said the school is located on park…Parkland and Douglas?”

That’s what happens in a large, consolidated 911 center, where dispatchers live and work several miles from the community to which they send help. Landmarks, like the massive 13 building high school campus in Parkland, are unfamiliar to them, contributing to confusion when seconds could mean life or death.

Most students and teachers sent texts to family members instead of calling 911

During our investigation, we obtained over 200 of the 911 calls made during the mass shooting. The vast majority of those calls received by Broward County dispatchers were from parents, grandparents, and other relatives who had received texts from their loved ones inside the school.

“There’s a shooting, call 911” read many of the texts, without offering any more details.

Dispatchers spent several precious minutes during the shooting talking with family members who had little information about what was happening.

Broward fielded 911 calls transferred from as far away as Indiana and New York City, as relatives who received text messages from inside the school called 911 in their home cities.

Some students had no choice but to send texts, for fear of alerting the gunman by talking to 911. However, it is clear that teenagers in particular are so used to text messages as their primary means of communication, their first thought in the emergency was to send texts for help.

Coral Springs could have sent police, but waited

After the initial alert of a school shooting in progress, Coral Springs dispatched fire trucks and ambulances, but not police.

Coral Springs 911 followed its standard procedure of transferring police-related 911 calls to Broward County.

Coral Springs Police were not notified over the main frequency for more than four minutes. A police sergeant noticed all the fire trucks and ambulances, and asked his dispatchers what was going on.

When a school is targeted by a mass murderer, the victims don’t care what the logo says on the side of the police car that’s sent to help. Eventually, multiple South Florida police agencies responded to the incident – too late to save a single victim from the shooting.

Max Schacter summed it up. “I’m very scared that the next attack is going to happen, and we’re going to have the same delays in law enforcement getting there, contributing to massive loss of life just like here, and I don’t want any family to have to go through the pain and anguish that I go through every day.”

LOST ON THE LINE: An 11Alive Investigation