Expanding Medicaid: The debate, the cost, the impact on Georgians

In this series, we’ll look at the politics behind expansion, analyze what it would cost state taxpayers and take a closer look at campaign promises around the issue.

The Peach State has spent over a decade debating Medicaid expansion. And as voters near the 2022 General Election on Nov. 8, this issue has become a key one in the governor's race.

People still have varying questions about the debate over the program, and11Alive is pushing beyond campaign rhetoric to look deeper into what expanding this health care program means.

This four-part series will air every night on 11Alive and our YouTube channel at 6 p.m. through the week of October 4. Watch the videos at the end of each section as they are released.

Explaining the Medicaid expansion gap

Suppose the phrase "closing the Medicaid expansion gap" operates on the notion that everyone should have some health insurance. In that case, the gap represents the financial barriers that keep potential applicants from receiving it.

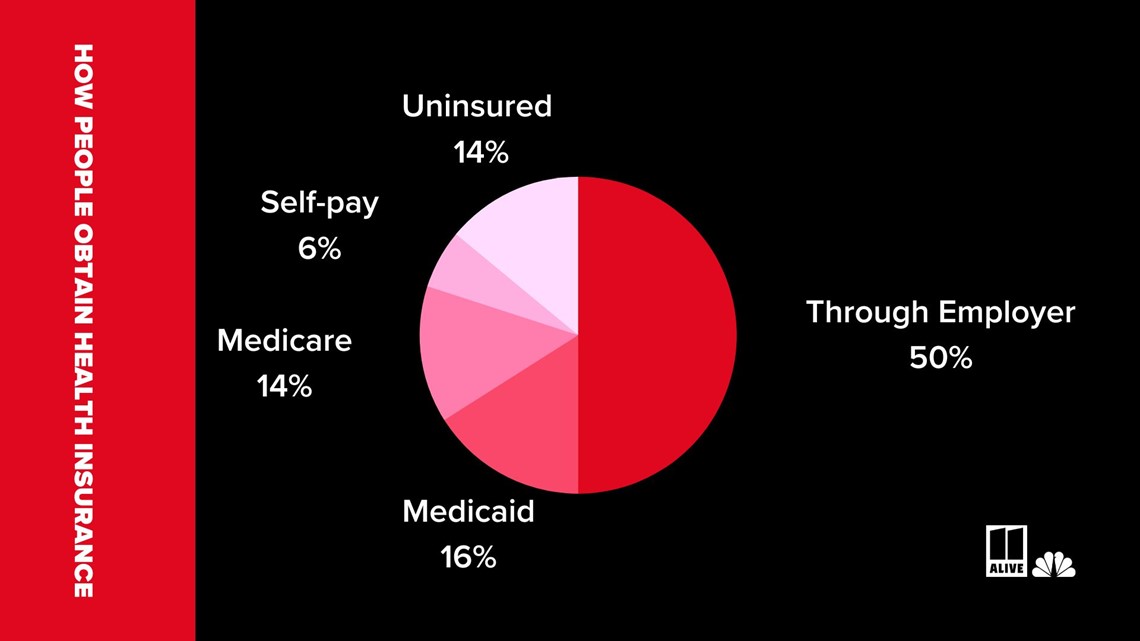

People qualify for health insurance in several ways, with half of those insured receiving it through their jobs. For the other half, there's 16% on Medicaid, a program that helps low-income families, individuals and people with disabilities; 6% buy it themselves, and 14% of seniors end up on Medicare.

That leaves another 14% of people without health insurance; in Georgia, that's 1.4 million people.

When politicians are referring to closing the Medicaid coverage gap, it often only accounts for a third of those people, mainly adults without children or disabilities. Advocates said they are the ones that kind of got lost in the shuffle when Congress passed the Affordable Care Act.

Want more | Links, sources, campaign statements

Kaiser Family Foundation broke down the numbers. The politically independent non-profit studies health policy and has spent years trying to understand the discussion around insurance coverage for low-income families.

For a family of three in Georgia, the household taxable income has to be less than $7,600 a year to qualify for Medicaid in Georgia. One dollar more, and the adults have to buy health insurance themselves, and options on the exchange show buying a plan would cost about $11,000. That’s not possible.

The federal government agreed to offer tax credits to cover or heavily subsidize the cost of buying a plan out of pocket. However, by the same law, adults can't receive the credits until their housing income is at least $23,000. Until the family reaches that income, there's nothing to offset the cost, hence the gap.

A second example is a person without kids. They don't qualify for Medicaid nor tax credits to buy health insurance until they make at least $13,590. There are 38 states in the U.S. that have decided to increase Medicaid eligibility to help push those struggling to the other side of the canyon. But 12 states, including Georgia, have not.

Democratic vs. Republican political philosophy on Medicaid

Georgia has the third-highest number of uninsured people in the nation. Though anyone can look at campaign ads, press events and Twitter and see the gubernatorial candidates only agree that more people need insurance, but not how we get there.

“We’ve got to do something to lower cost and provide more access,” Gov. Brian Kemp said at a campaign stop. “The solution is not more government.”

Democratic challenger Stacy Abrams countered at her campaign event: "We know that there are lower rates of health coverage in large part because southern states have refused to expand Medicaid."

Part of that divide stems from basic party philosophies between the U.S. Democrats and Republicans.

"The Democratic party has become the party of social safety nets. In contrast, though, the Republican party has espoused a much more individualistic market-based approach; this is not the work of government," Andra Gillespie, Emory political science associate, said.

That’s why in 2019, Kemp approved an alternative plan to help low-income citizens access health insurance, as long as they were in school, worked or volunteered 80 hours a month.

“Part of it is the idea [is] that work is dignified. Everybody should participate," Gillespie explained. "But there are also perceptions about why people are not working. That there are people who are scamming the system. They’d rather live off the government than work."

The plan helps provide free or low-cost access to insurance for those at the federal poverty level, or FPL. This program did not provide additional access for those who make between 100-138% FPL. These people usually work in the gig economy, like Uber drivers and other fee-for-service jobs.

“There’s a lot of churn in that population, and what I mean by churn is, people’s income fluctuates a lot month-to-month, year-to-year," Erin Fuse Brown, Director of the Center for Law Health and Society at Georgia State University, said. "And so they may qualify for Medicaid in one month, but then they may drop out of qualifying because they made a little more."

Fuse Brown added that this makes it challenging to manage a chronic condition, like diabetes, and explained this is why Congress has insisted they be part of the full expansion plan.

“It is more efficient, but also better care, to just allow people who tend to have this income fluctuation to stay on Medicaid,” she said.

The Biden administration quickly informed the state that the work requirements also unfairly burden citizens. Think of people without an internet connection or those who can’t work 80 hours a month because they are full-time caregivers to a disabled child.

“It causes fewer people to qualify for Medicaid coverage even if they were to be eligible just because they can’t keep up with the record keeping requirements,” Fuse Brown said.

But in August, a U.S. District Court Judge sided with Kemp, allowing the Georgia Pathways program to move forward with the work requirement.

Aside from their issues with the work requirements, critics also pointed to the program's cost. The state's court filing said Georgia would need to hire 117 employees to administer the program and had already spent more than $27 million to implement it.

Additional employees would also be needed to process and manage new enrollees that would gain access through a full expansion of Medicaid. The difference, since there wouldn’t be new requirements to track and maintain that coverage, the administration would remain the same.

But Kemp claims Medicaid is a bad program -- not enough doctors accept it, and costs keep rising. With state sovereignty at the forefront of their ideology, Republicans don’t want to rely on too much federal funding.

“Governor Kemp is going to make this an issue of thinking about government intrusion, about not expanding the state and bloating it beyond what it should be providing for voters,” Gillespie said.

Abrams wants the federal government to pay 90% of the Medicaid tab and join the 38 states that have expanded Medicaid. With Georgia holding back on expansion, our federal tax dollars are being split between the states that said yes, with none coming back.

“Costs are going up everywhere, this is a way to expand insurance access to people who actually need it,” Gillespie said.

Democrats assert that expansion makes sense for the economy as a whole.

“You never know when you’re going to get into an accident, come down with a chronic illness," Gillespie added. "So, the more people that get covered means that you don’t have people who are going to be forced into poverty because they had access to no health care."

But at the heart of the opposition, Fuse Brown said, is who started the push for expansion.

“The Medicaid expansion was part of Obamacare, right? It was part of the Affordable Care Act, which was the signature domestic accomplishment of President Obama,” Fuse Brown explained.

And it's hard to ignore that the 12 states declining to expand Medicaid coverage have either a Republican governor or GOP-controlled legislature.

“I think that the argument against it is mostly ideological,” Fuse Brown said.

The cost of expanding Medicaid in Georgia

Right now, Georgia has two plans on the table, and the numbers on what they would cost are all over the place, but the basic trend remains -- expanding the program is less.

A 2019 analysis from the Georgia Budget and Policy Institute (GBPI) broke them down into Plan A and Plan B. The first, Plan A, would close the gap and expand Medicaid to nearly 482,000 people. This would cost state taxpayers around $500 for each new person covered.

The Plan B that GBPI looked at is Governor Kemp’s plan. This would insure about 32,000 people in its first year if they performed enough volunteer, school or work hours. And even though this plan covers fewer people, it would cost nearly five times more a person for taxpayers, about $2,420.

The price difference is stark, and it has a reason, Plan A has federal backing.

“The way that the law and this expansion is set up is that under the current rules, the federal government does pay the vast majority of the cost of expansion,” Robin Rudowitz with the Kaiser Family Foundation, a non-partisan organization, said

With Plan A, Georgia would fully expand Medicaid triggering the federal government to pay 90% of the cost as an incentive. Congress is essentially offering the state roughly a $1.5 billion bonus. But if Georgia sticks with Plan B, it forfeits the money, and the federal government would only pay about 67% of the bill.

“We really are missing out on billions in federal revenue,” Leah Chan with the Georgia Budget and Policy Institute (GBPI) added.

And studies show full expansion comes with savings in other areas.

“Many states fund mental health services for individuals who don’t have insurance coverage with state-only dollars." Rudowitz said. "If you adopt expansion and people are newly-eligible for coverage, states may be able to access federal support for some of those services.”

One wallet Medicaid expansion would impact is small business owner Amy Bielawski.

“My company, Hare-Brained Productions, is an entertainment agency -- face painting, balloon sculpting, belly dance, fire eating,” Bielawski said.

It’s a seasonal business. Some months are good. “Beginning of the year is always bad,” she quickly added. Despite having a job, Bielawski doesn’t have health insurance. She tries to get by with free county health clinics. So, when people talk about closing the Medicaid gap, she pays close attention.

“It seems like a no-brainer, really. You need people to keep the community going as workers, but you also need to take care of those people health-wise," she said. "I’m not asking for it for free. Just make it affordable.”

But when your taxable income is about $1,100 a month, she said there’s not much left after you pay for rent, food and utilities.

Critics of Medicaid expansion claim that taxes are taxes, whether they are state or federal. They question what happens when the federal government decides it no longer wants to foot the bulk of the bill.

“There’s no penalty if states have expansion and then choose to not continue that,” Rudowitz countered quickly.

But, it’s hard to cut back a program once it exists, Bielawski knows. During the pandemic, she qualified for unemployment and health insurance.

“I had health insurance for a whole five months," Bielawski said. "As you get older, it does matter, unfortunately.”

Chan and Rudowitz said that’s where the push for Medicaid expansion comes in.

“People don’t fully appreciate that adults without dependent children -- just there is no pathway. Even if they have zero income,” Rudowitz said.

She pointed to data reflecting that 49% of those who fall in the gap have jobs, and at least 45% are people of color.

“It is critical that we provide a pathway to affordable healthcare coverage for these Georgians that, for so long, have been locked out of economic opportunity,” Chan said.

Expansion of Medicaid and the effect on Georgia's economy

Supporters of Medicaid expansion say it's more than offering insurance to those with a low income but also believe it would improve the economy.

Democratic gubernatorial candidate Stacey Abrams said in her ad that the expansion would create 64,000 new jobs and help save rural hospitals.

“Rural hospitals in particular are safety net hospitals,” Chris Denson with the fiscally conservative group Georgia Public Policy Foundation said.

The Georgia Hospital Association said they treat a higher percentage of people on Medicaid or uninsured. So, increasing the number of people with insurance will increase the amount these hospitals get paid.

People don't have to go to a rural area to understand the impact of unreimbursed care on our community. Wellstar announced in September that it would close the Atlanta Medical Center, which houses a level-one trauma emergency room, leaving Atlanta with only one in the city.

This move came just months after Wellstar closed the emergency room at AMC South in East Point.

Still, Denson argues that since Medicaid reimbursements are lower than the actual cost of care, full Medicaid expansion would only slow the bleed. Not cure the wound.

As for jobs, the theory is that the more people who have insurance, the more people who will go to the doctor.

“So that’s new jobs in health care, that’s new jobs in construction and retail, in folks working in the financial and insurance industry," Chan explained.

But Denson pointed out we’ve expanded Medicaid several times in the past 20 years and, by his analysis, the impact on health care jobs has been mixed. Plus, coverage doesn’t directly correlate to access.

“Only 64% of healthcare providers accept Medicaid patients, and only 60% of those are accepting new Medicaid patients,” Denson said. “We currently have, I believe, 63 counties without a pediatrician and 79 without an OBGYN.”

And in those rural areas, he believes low Medicaid reimbursement rates aren’t likely to attract new providers. That’s why Kemp said he’s focused on trying to move people onto private insurance.

“Commercially insured patients, the reimbursement rate for hospitals is above cost. Most rural hospitals survive on commercially insured patients,” explained Denson.

The cost associated with commercial insurance is still too high for someone working a minimum wage to afford. One way to achieve this, Denson said, is to "increase the number of providers in a lot of our, what are known as health provider shortage areas," forcing companies "to be more competitive."

Denson has some ideas on increasing providers, but they all take regulatory change and time. Supporters argue Medicaid expansion is a fix for right now.

Kaiser Family Foundation reviewed over 600 studies over the past decade since states began expansion. KFF reports that most of those studies found that access to care, financial security, the health of residents and the economy improved in states that fully expanded Medicaid.

“Access to health care can help us meet our basic needs in a way that allows us to contribute at home, at school, at work and our community. And it really is just a basic human right,” Chan said.

Several questions have floated around this issue, but the three main ones surround whether healthcare is a human right, the role of government in paying and if Medicaid is the right type of insurance to offer.

Those are questions voters will answer when they head to the polls.

Want more | Links, sources, campaign statements