A man is beaten and strangled to death, and a woman is serving a life sentence for his murder. But does the evidence that sent her away for life, lack true forensic credibility—and will it be the key to unlocking her prison cell?

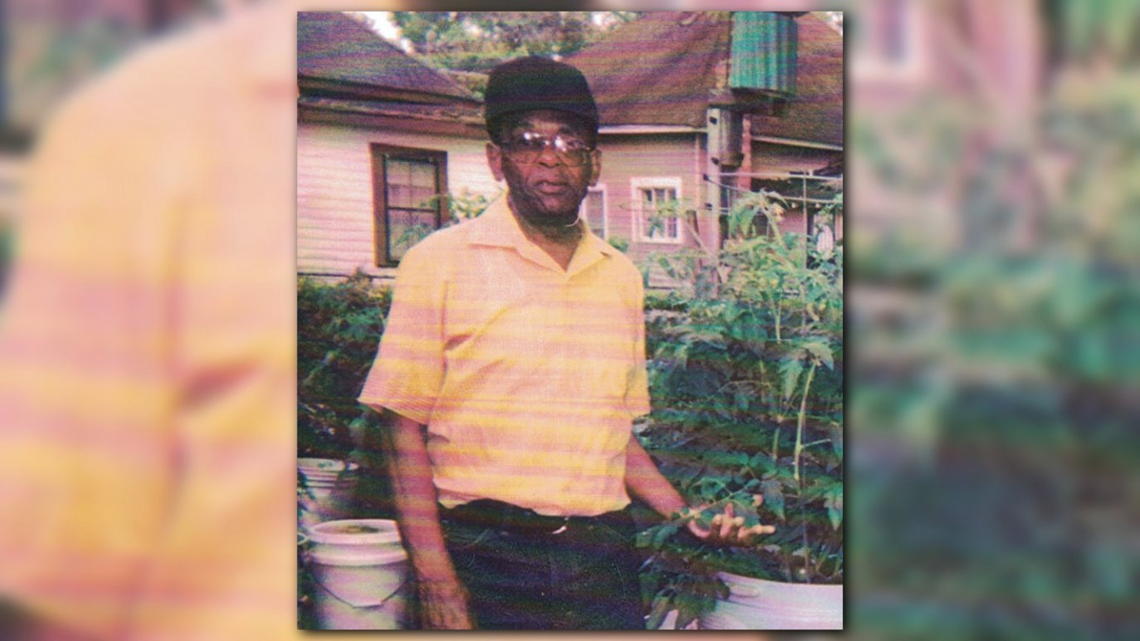

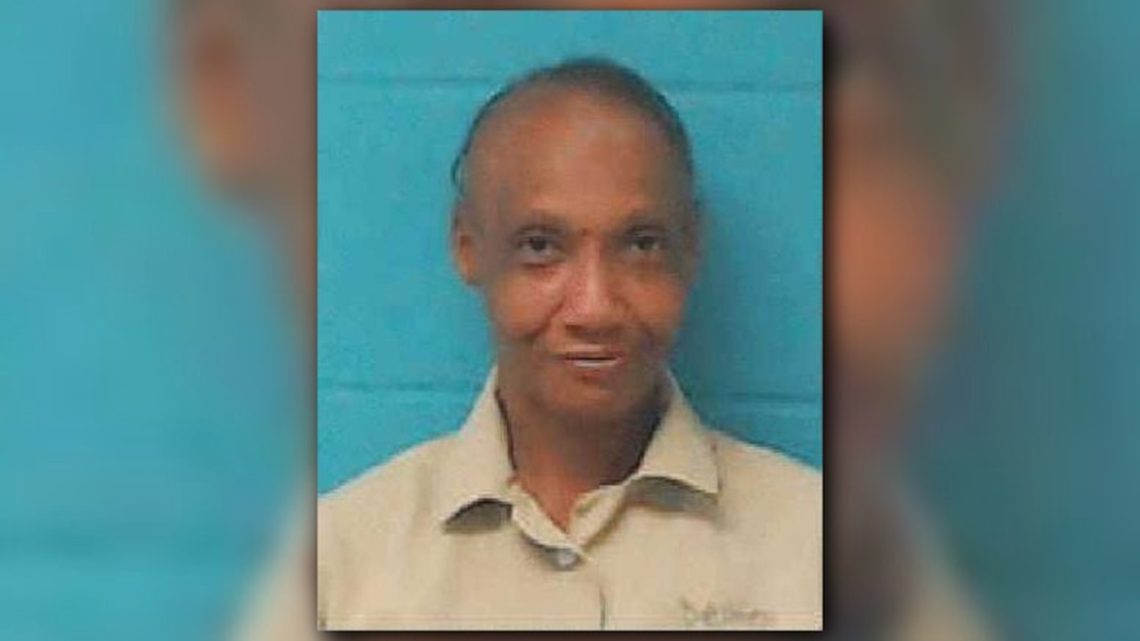

Sheila Denton, 51, is 12 years into her life sentence in Arrendale State Prison for the 2004 murder of 73-year-old Eugene Garner.

But did she do it?

Mark Loudon-Brown, with the Southern Center for Human Rights in Atlanta, says the only evidence the Ware County district attorney hung his case on was alleged bitemarks found on the victim and the suspect: Denton.

According to the vast majority of forensic scientists, though, bitemark evidence is fast becoming a piece of flawed forensics that doesn’t hold up in court. And those experts are rallying to get it thrown out altogether.

In fact, several people who had been convicted across the country are now exonerated or have been granted new trials based on evidence that Innocence Project attorney, Chris Fabricant, calls junk science.

“Every single scientific entity that has looked at bitemark analysis has come to precisely the same conclusion…it’s garbage, it should not be used in court.”

That’s why Denton’s new attorney, Loudon-Brown, says she deserves a new trial.

But the victim’s sister says, absolutely not.

“I don’t think she needs to get out. I think she needs to die there. That’s the way I feel,” Ruth Taylor said.

She still remembers the pain her brother’s murder caused her and her family.

“Oh lord, I didn’t think I was going to make it. To tell you the honest truth, I didn’t think I was going to make it. She just took part of my life away from me.”

No stranger to jail cells

While her fate on a 12-year-old conviction is being determined inside a Ware County judge’s chambers, Denton’s past, prior to the murder, wasn’t squeaky clean.

In fact, she had several run-ins with the law in Waycross, Ga., alone—including drug possession, assault and theft.

• Aug. 13, 1999- Forgery

• March 16, 1999- Probation violation, disorderly conduct for a fight in Walmart. Denton was heard saying, “I’m going to kill that bitch.”

• Dec. 15, 1998- Disorderly conduct, family violence – Denton called the police on her husband for punched her in the face.

• Nov. 7, 1997- Simple battery – Denton called police beat her up.

• March 28, 1997- Theft by taking – Denton is accused of taking two checks and $620 from Mary Brown.

• Oct. 11, 2000- Robbery by strongarm, aggravated assault, party to crime-robbery/snatch, robbery by snatching

• Aug. 10, 2002- Forgery of checks

• Dec. 13, 2002- Cocaine possession, marijuana possession, possession of prescription, Lorcet

• April 29, 2003- Theft by taking

• June 1, 2004- Forgery of checks – Denton is accused of writing and cashing checks from an account that is not hers in the amounts of: $400, $150, $800.

• May 19, 2004- Aggravated assault, burglary

State of Georgia v. Sheila Denton | CASE NO: 04R-330

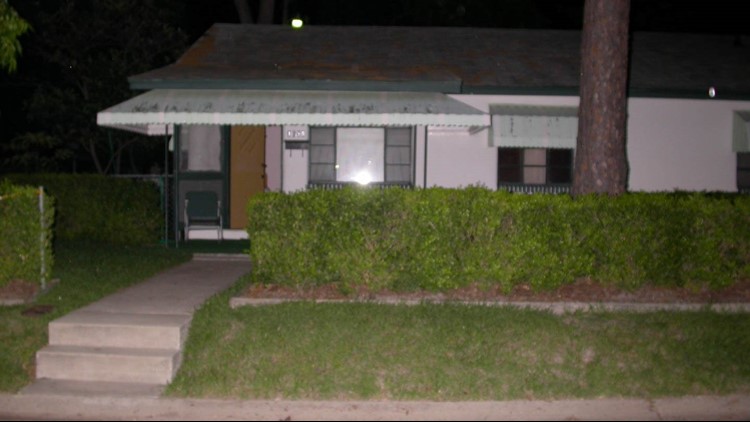

On May 21, 2004, Eugene Garner’s body is found at his residence, at 1638 ABC Ave., in Waycross, Ga., by a concerned neighbor who hadn’t heard from him.

It’s a grisly scene.

The Georgia Bureau of Investigation is called in to process the crime scene and the investigation is handled by the Waycross Police Department.

Waycross Police respond to Garner’s home at 7:39 p.m. to investigate his death.

It’s dusk out and there aren’t any nearby streetlights at 1638 ABC Ave.

As they enter the front door, they hear the phone ringing.

With a flashlight in hand, illuminating each room, officers move through the quiet, single-story, white house.

There are drops of blood on the kitchen wall.

“I wonder if he saw that…” one of the officers says.

Inside the bedroom, the sheets are drenched in blood.

On the floor, Garner lies face down between the bed and dresser. His head is next to an empty green laundry basket and a pair of brown slippers.

His nose and several bones in his face have been fractured.

Coroner Atha Lucas pronounces him dead at 9 p.m. He has suffered blunt force trauma to his head and was manually strangled to death.

At 10:05 p.m., GBI Special Agent Jeff Roesler arrives to process the scene which is now secured with yellow crime scene tape. He meets with special agent, Tom Crawford, Waycross Police Department Capt. Tony Tanner and Det. Mark Woods.

There are two cars parked in the driveway—a blue GEO Metro and a tan Pontiac Bonneville.

Upon entering the house, he notes that the front door is open, the windows are all locked. The back door and the back gate to the metal, chain-linked fence, are closed and locked.

He’s advised by the officers on scene that the homeowner, a 73-year-old black man, is face down on the floor in his bedroom.

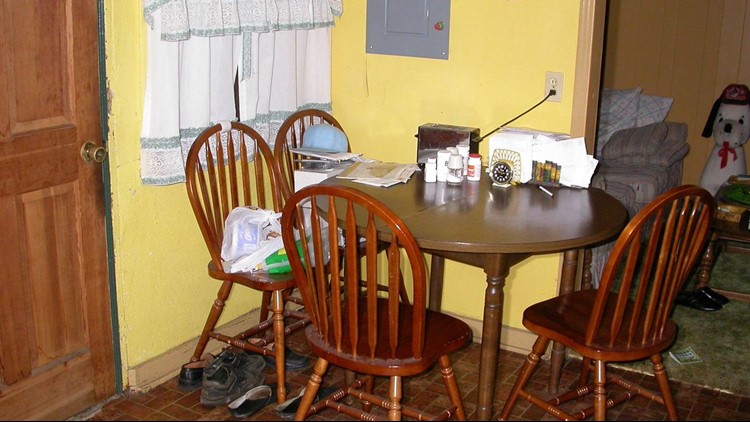

As he moves inside the house, he notices two Jumbo Bucks Classic scratch-off Georgia Lottery tickets, already played, on the living room floor.

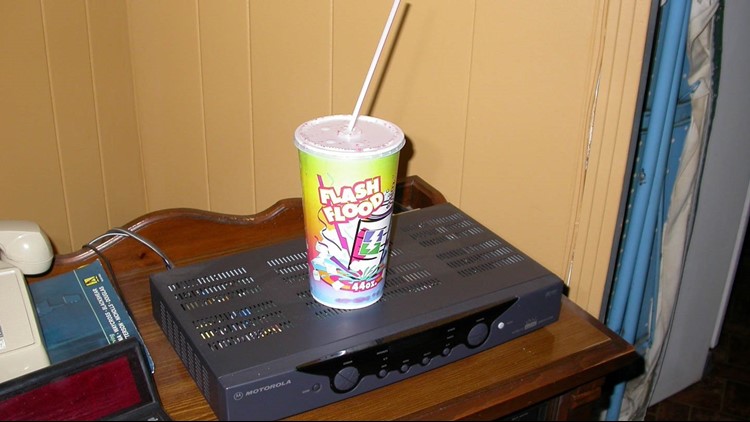

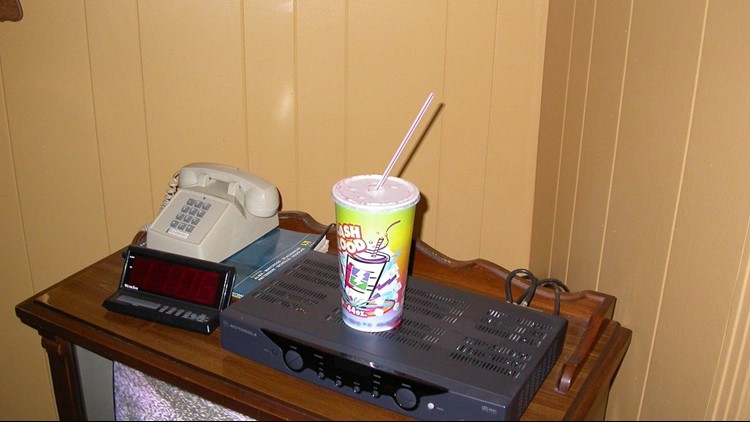

The T.V., is on and set to channel 3, giving the room an eerie glow.

In front of a white phone, large, red digital numbers on a clock on top of the T.V., show 11:31.

On top of the cable box he sees a Flash Flood 44-ounce drink cup with a lid and straw—red liquid has started leaking out from the cup. The drink and lottery tickets are the only items that seem out of place in the victim’s otherwise neatly kept living room.

Deeper inside, however, a vase with a flower arrangement inside is strewn across the floor and a lamp has been knocked off one of the end tables next to a pink chair. An off-white Kango hat is laying underneath the end table.

In the hallway, a blinking answering machine indicates four unheard messages. The phone rings several times as he continues processing the scene.

Just outside the bedroom door, Roesler notices blood on the carpet. As he walks beyond the door frame and into the bedroom, he notes that the comforter and sheets are pulled back off the corner of the bed.

A pair of blue plaid pajamas are sitting, unscathed at the end of the bed on top of a blood-soaked, blue-pattern quilt.

Blood encases a black and brown men’s leather belt with a gold buckle lying on the floor.

But as he inches closer to the victim, the scene is something more gruesome than out a horror flick.

There’s blood spatter near the window.

On the wall.

On the bed.

And a heavy odor of hydrogen peroxide permeates the room.

The victim has short black hair and is wearing green pants and black and multi-colored socks.

There is blood on his pants leg and in the gold of his pin-striped shirt, which is pulled up to his shoulders, exposing his white tank top. The front of the tank is saturated in blood.

His left arm is bent at the elbow, which sustained several injuries. His left forearm and hand are situated underneath his torso. His right arm is bent at the elbow and out to his side. His right hand is clinched and next to his head.

There is a substantial amount of blood pooled on the ground near and around his head, as well as an open wound, with dried blood, on his left cheek.

Blood is also on his right hand and forearm.

In his fists, he’s tightly gripping several black hairs. Roesler pulls out the hairs with tweezers and places them into a clear, plastic Ziploc bag for further analysis.

Investigators uncover no suspicious fingerprints nor DNA at the scene.

Flawed Forensics | The crime scene

On May 22, police locate Denton, who admits to having a relationship with Garner. But she gives them three fake names and then runs into a wooded area away from police, who once they locate her, point their taser at her and instruct her to lay on the ground.

She defies them and begins taking off her dress.

Officer Michael Millwood shoots Denton with his Taser in the stomach and she falls to the ground. He tells her to roll over on her stomach and place her hands behind her back.

Again, she refuses. So, he shoots her with his Taser and Det. Morris handcuffs Denton, who admits to smoking cocaine. According to police, she’s highly intoxicated.

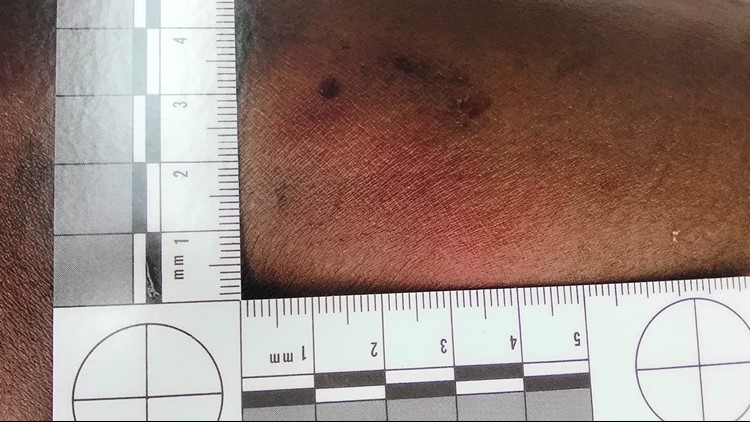

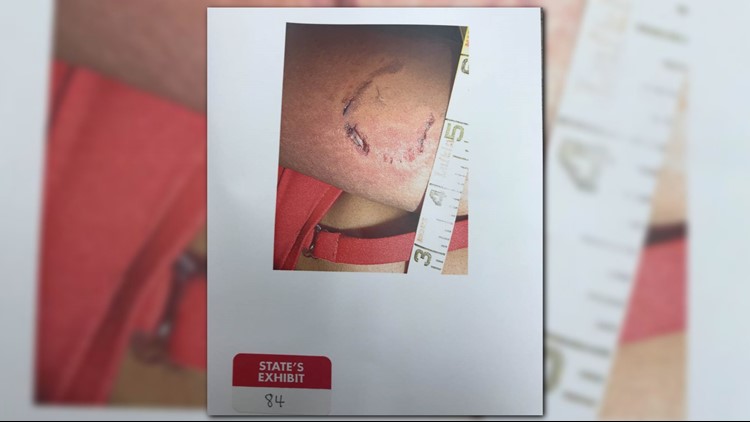

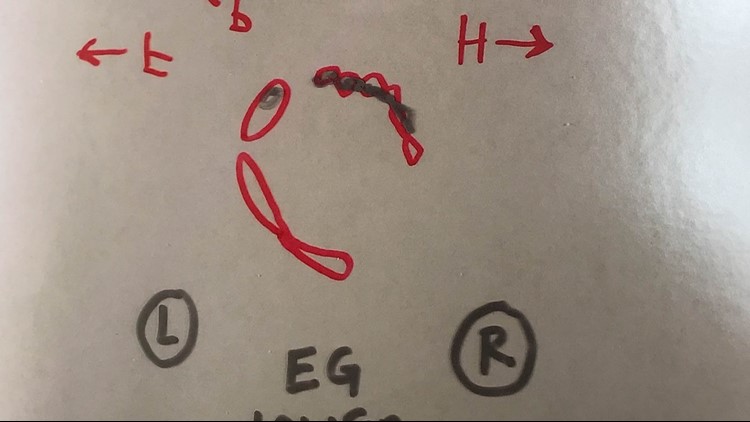

The detective notices that she has a sore—which he believes is a bitemark—on the left tricep area of her arm.

He also notes that she’s missing a clump of hair from the top of her scalp—which has seemingly been pulled out recently. She is taken in and her injuries are photographed at the police station.

Det. Grant attempts to interview a slumped-over Denton, 37, however, she tells him that she does not want to talk to him.

Leaning against a cinder block wall and wearing a pink jail shirt, she acts “nostalgic and unresponsive” as they continue to probe her about Garner’s murder.

“Shelia, I’m Det. Woods…You need to wake up. Take a swig of [this] drink.”

“I’m not talking until tomorrow.”

Woods informs her that they are applying for a search warrant for her fingernail scrapings, blood and hair samples.

After leaving the interrogation room, detectives observe her on camera scratching at the wounds on her arm and scraping her fingernails.

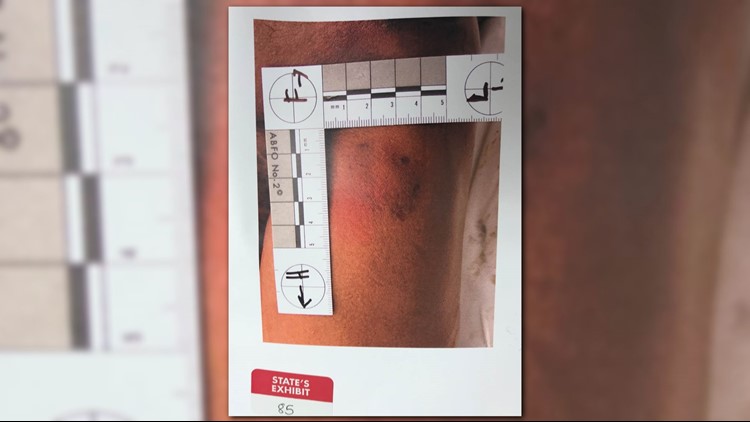

Two days later, Grant takes Denton to the hospital to carry out his search warrants to obtain two tubes of her blood, hair samples from her head, left and right-hand fingernail scrapings and photographs of her injuries, including, what investigators believe to be, two bitemarks on her left arm and injuries to her right-hand fingers.

Meanwhile, Anthony Clark, assistant medical examiner with the GBI crime lab, determines that Garner’s manner of death is homicide and the cause of death is manual strangulation and blunt force trauma to the head from being beaten with an unknown object.

On Wednesday, June 9, 2004, an arrest warrant is issued for Sheila Denise Denton, charging her with Garner’s murder.

The warrant is served to Denton at the Ware County Jail at 1:50 p.m., where she was in custody on other charges.

Woods reads the warrant to Denton. She shows no emotion and does not ask any questions.

He asks her if she understands what she is charged with and shakes her head no.

Denton is charged with malice murder, felony murder and giving false name.

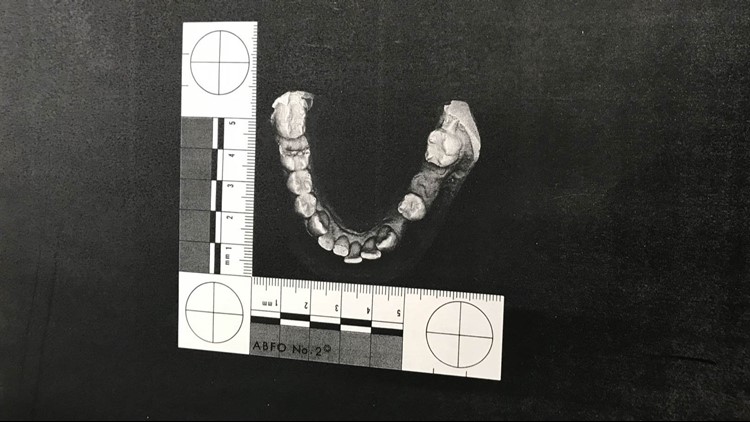

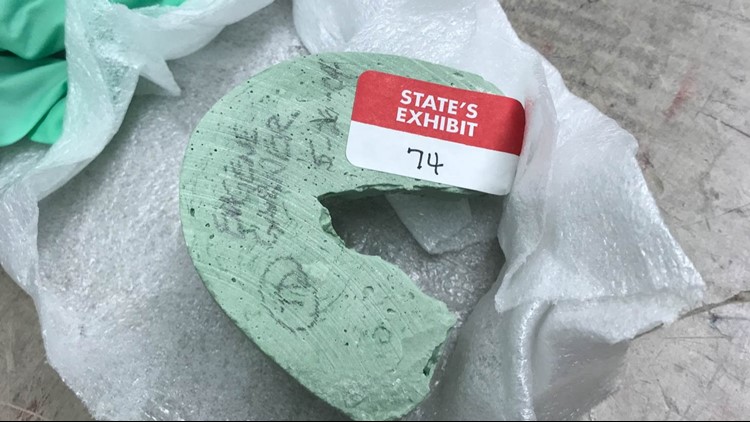

On June 10, 2004, with a search warrant, Denton is taken to Dr. Jeffrey Cauley’s office for him to collect her dental impressions.

On Aug. 4, 2004 at 10 a.m., an investigator picks up local drug dealer, Sharon Shontaey Jones, who’s employed at McDonald’s on Memorial Drive. She tells police Denton is “no good.”

“She don’t care who she hurt. She don’t care what she say. She don’t care,” she says.

She also admits to selling crack cocaine to Denton the night Garner was killed. And says Denton had more money on her that night than usual.

Garner was known to have wads of cash in his wallet, his family said.

His sister remembers telling him the week before he was killed to be careful with his money.

“I had just told him the week before don’t pull all that money out of your wallet at one time,” Taylor said. “He had a roll of money big enough to choke a cow.”

“Everybody that dealt with him, that was around him in a length of time knew that he all this money in his pocket,” she said.

After picking Jones up and taking her into the station, Sgt. Hilton Boyett gives Jones a polygraph test, which indicates deception.

At first, Jones tells police, she doesn’t know anything about Garner’s death.

Detective: “Have you talked to Shelia Denton since she’s been in jail?”

Jones: “No.”

Detective: “Did Sheila ever tell you that she killed him?”

Jones: “No… No.”

Detectives tell Jones they have a tape of someone putting her at the scene of the crime, and she begins to break down.

Detective: “Why would there be any reason why they saw you over there?”

“I wasn’t there!” Jones says crying.

Detective: “You need to decide right now whether you want to be a witness, or you want to be a suspect?”

Jones: “I don’t want to be no suspect!”

Detective: “Well, you need to tell me the truth right now!”

Jones: “I’m telling you the truth!”

Detective: “Stop jacking me around.”

Jones: “I’m telling you the truth!”

There is no tape.

A few hours later, Jones changes her story.

She says Denton came to her house with blood on her arms and legs and confessed that she had killed a man.

Just before noon, Jones reads her handwritten letter on camera to Woods.

There was a knock on the door about 4:30 in the morning.

I said, “Who is it?”

“Sheila.”

At first, I said, “No, I can’t let you in.”

She said, “Please open the door.”

I open the door and she said, “I just did something.”

“What have you did?”

“I just killed somebody.”

“Who?”

“The man in the front of Wally’s.”

“Sit down and how your arms and legs got like that?”

She said, “It’s OK.”

But Loudon-Brown said Jones’ police interrogation, and the admission that followed, has all the hallmarks of a coerced statement.

“They told her they had her fingerprints at the scene of the crime, he said. They told her they were going to lock her up…her words were, they kept saying I did…”

Detective: “I know you know the man…!”

Jones: “I don’t know him!”

Detective: “I got people placing you there…!”

“So, basically, it was only after being presented with this false evidence that she suddenly came up with this idea that Ms. Denton had made this brief admission to her,” Loudon-Brown said.

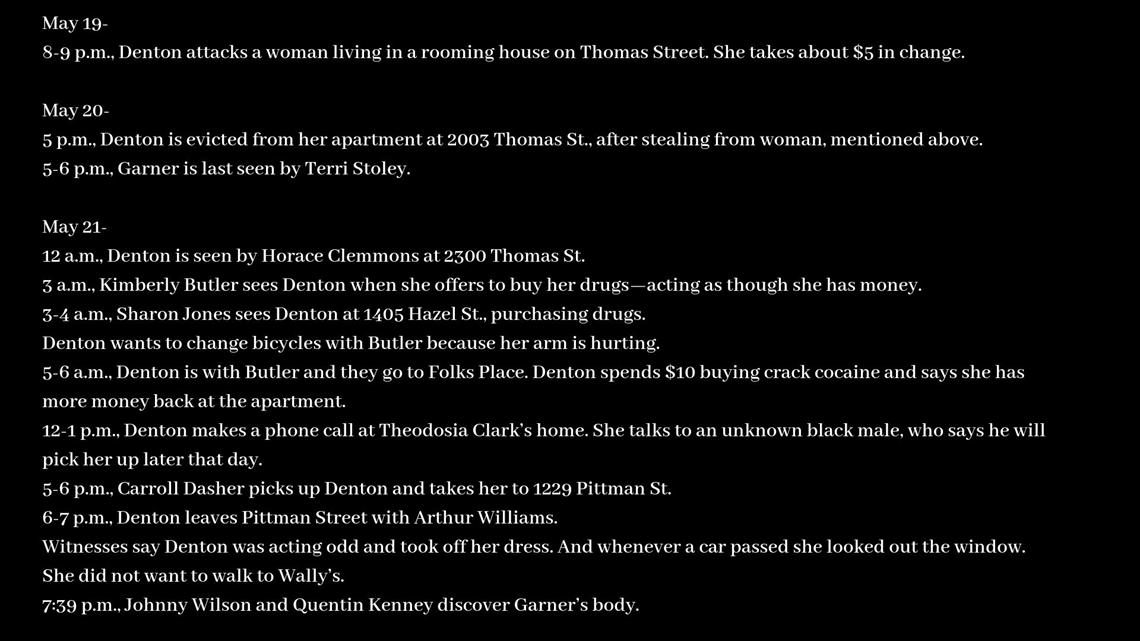

According to police, the following is the timeline leading up to and after Garner’s murder, after conducting witness interviews, like with Jones.

On Aug. 13, 2004, a grand jury indicts Denton on malice murder, felony murder and giving false name charges.

Two years later, she stands trial.

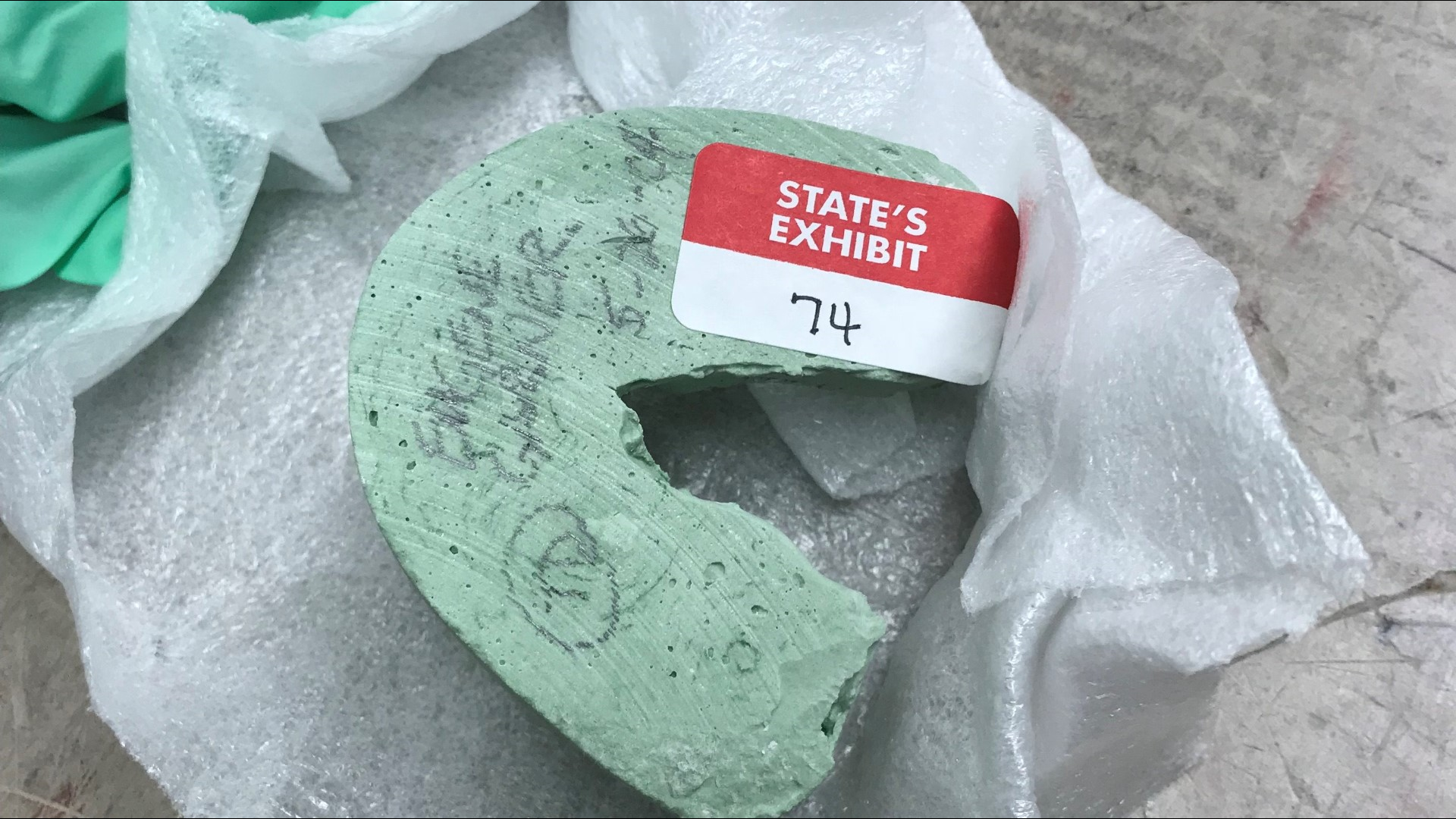

Flawed Forensics | Inside the bitemark evidence file

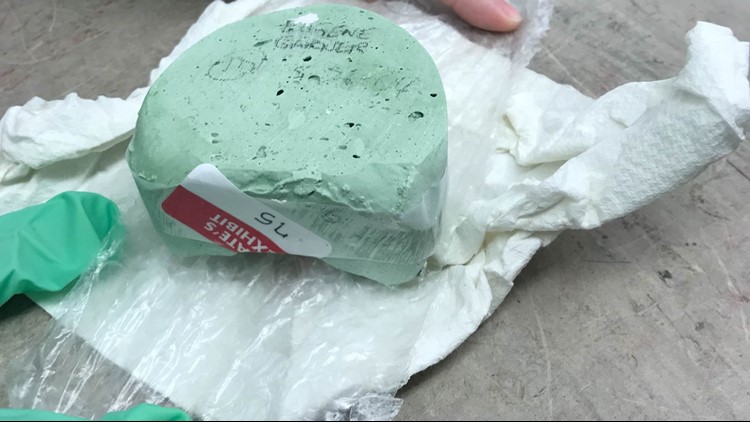

Among the state’s physical evidence is Denton’s fingernail scrapings, blood, her dress, hair and bitemarks on both her and the victim.

Samples of those are submitted to the GBI crime lab on May 24, 2004.

Nearly eight months later, on Jan. 13, 2005, Barbara Retzer, forensic biologist with the GBI crime lab, examines Garner and Denton’s blood samples and items, including the dress Denton was wearing.

In her conclusion, she states, that a chemical examination of the dress fails to reveal the presence of blood.

On July 5, 2005, Terri Santamaria, microanalyst with the GBI crime lab, examines the hair found in Garner’s hands. She concludes that the hair is consistent with his own hair and therefore will not be transferred for DNA analysis.

Further, the comparison between Denton’s hair and Garner’s hair, results “dissimilar microscopic characteristics.”

“It is therefore concluded that the questioned hair did not originate” from Denton, Santamaria writes in her report.

And while fingernail scrapings are taken from Denton, they are never tested.

But the bitemarks would play a big role in her trial.

Thomas David, DDS, is paid approximately $4,275 by the prosecution, to examine the alleged bitemarks on both Denton’s and Garner’s arms and then testify to his findings.

In his conclusion, he states:

Based on an evaluation of all evidence available, it is my opinion that the bitemark on the left arm of Sheila Denton was probably made by Eugene Garner. It is also my opinion that the bitemark on the right arm of Eugene Garner was probably made by Sheila Denton. I hold these opinions to a reasonable degree of scientific certainty. These opinions are subject to modification in the future if additional evidence becomes available at a later time.

In his closing arguments DA Rick Currie says to the jury:

I do admit and agree that the bitemark testimony that you heard from Dr. David is not like DNA. It is not as definitive. And if all we had that we came to you today was to say the bitemark – the one bitemark on the right arm of Eugene Garner. If that’s all we had, I’d have to admit that’s reasonable doubt. If that’s all we had that tied Sheila Denton to the death of Eugene Garner, then we would not have enough. But then we’ve got also the bitemark on Sheila Denton. That bitemark, and look at it closely, has had a little time to heal, a few days. That bitemark matches up with the dentures and the teeth of Eugene Garner.

I agree, not every tooth is different. It’s not like fingerprints that God gave only one fingerprint to every person. Teeth are a little different. That still doesn’t mean that we’ve got here – we’ve got a bitemark on a live person and we’ve got a bitemark on the dead man.

We also have other things including the bitemark. Motive, opportunity and means. Means is a little easy in this case because it’s not like she had to have access to a gun. All she had to have access to, was a rod-type, something of a rod. That’s not very hard to do or kicking. Opportunity, she had access to him. she knew who he was. She had the ability to go to his house. motive, money, crack cocaine. There is a trail of money in here.

The jury convicts Denton of murder, and on May 17, 2006, she begins serving her life sentence.

Forensic evidence or junk science?

11Alive sat down with Currie last month to talk about the case. Now, employed as the city attorney for Waycross, he said the bitemark was only corroborating evidence against Denton.

“Generally, it was the confession from [Jones]… I hate to say from a crack dealer—but in a crack house—and she made a pretty good witness. It’s not perfect, but it’s an admission to someone who could come in and testify,” Currie admitted.

“If I had not had the confession, it would have been [a] difficult case.”

But, he said, he would have had a conviction regardless of the bitemark evidence.

Further, he said, his expert witness did not give the opinion that it was Denton’s bitemark for certain—rather, that it was probable.

“He didn’t testify that in my professional opinion this bitemark was made by Sheila Denton…he said it was ‘probably.’”

Even without the bitemark, he said, he would have still gone to trial.

In 2016, a report by the President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology found “bitemark analysis does not meet the scientific standards for foundational validity,” calling it “subjective.”

And, that examiners “cannot identify the source of bitemarks with reasonable accuracy.”

At least 31 people incarcerated with bitemark evidence have been exonerated or had their indictments dismissed since 2005.

“Which is an incredible number if you consider how rarely bitemark evidence is actually used,” Fabricant said. “Every single case that the Innocence project that has puts its hands on in the last five years, every single one of those clients, has ultimately been released from prison.”

“I’m confident they are innocent and I’m also confident that the search for the truth that a trial is supposed to be all about is not advanced by bitemark analysis.”

In March 2016, and revised in February 2018, the American Board of Forensic Odontology (ABFO) published a new set of guidelines including prohibiting a “probable” conclusion concerning bitemark testimony—10 years after David’s “probable” conclusion in Denton’s case.

Today, experts may only testify regarding their conclusions if they are excluded, cannot be excluded or inconclusive.

John Kunco, of Pennsylvania, was one of those who was released earlier this year after serving 28 years for a rape in 1991.

David also testified for the prosecution in his case—and wrote an article in 1994 about it in the Journal of Forensic Science, and how he was able to “recapture” a bitemark with reflective ultraviolet photography five months after the rape—writing that the bitemark found on the victim was a “critical piece of evidence” and without it, there would have been no conviction.

“Without this critical piece of evidence, it is unlikely that there would have been sufficient evidence to support a conviction for this vicious crime,” he wrote in the article.

According to the Innocence Project, Kunco’s conviction was due in large part to bitemark evidence presented to the jury.

This past March, a judge also released Alfred Swinton after DNA evidence showed he was not the source of bitemarks related to a 1991 homicide in Hartford, Conn.—after spending 18 years in prison.

“The dentists that are involved in this work are putting their heads in the sand for the most part, and continuing to insist, with no evidence at all,” Fabricant said.

It’s going to take a court to hold a hearing to stop any future wrongful convictions.

“It just takes one court to really actually holding a hearing, bring in all of the experts, let’s have a debate, right…let’s read the literature…let’s look at the wrongful convictions…let’s look at the data…and I think that any fair weighing of the evidence would exclude bitemark evidence forever.”

“If we care about life and liberty issues…we should only care about valid and reliable science being used in criminal trials,” he continued.

Four hours and more than 250 miles from Waycross, Mark Louden-Brown with the Southern Center for Human Rights in Atlanta started looking at Denton’s case in 2016.

Denton has maintained her innocence to Loudon-Brown.

In November 2017, Loudon-Brown filed a motion for a new trial.

“Whether or not she got a fair trial, which I don’t believe she did, we now know today why she didn’t get a fair trial because we have a much better understanding of why bitemark analysis is not reliable,” he argued.

The state’s evidence rose and fell with the bitemark and the subsequent expert testimony David gave, he said.

“And when jury hears that, that’s tough to overcome. It’s tough for a lay juror to discount an expert opinion.”

For his hearing, requesting a new trial, he called upon five of his own forensic dentists to review the evidence.

“They all said that the injuries in this case were either not bitemarks, definitively not bitemarks or were inconclusive at best,” he said.

Further, he rebutted, the hair in the victim’s hands weren’t Denton’s. It was the victim’s own hair, according to the abovementioned GBI crime lab’s analysis.

“The testimony in trial was that it was his own hair, which is strange, because you think if you’re in a struggle with someone, you would pull out the other person’s hair.”

According to Loudon-Brown, there were reports about a neighbor who broke into the victim’s home. But no real follow-up was conducted.

“My conclusion was that they found what they thought was the bitemark and case closed.”

Waiting behind bars

She’s known as inmate number: 0001213232.

But to two little girls, she’s just “grandma.”

The mother of two, now-52, gets to visit with her granddaughters, who are 1 and 4 years old.

But only from inside prison walls.

Her family says, that while yes, she was a drug addict—she is not a murderer and doesn’t belong in prison for the rest of her life.

“I just knew that she wasn’t the type of person to commit such a horrific crime. My sister was a nice person…she doesn’t have a malicious bone in her body,” Collins said.

Before she was convicted, her 59-year-old sister—and one of seven siblings—Vanessa Collins says, Denton was a nurse at a nursing home.

Denton’s son, Ricky Allen, 30, lost his mom and his mobility all in the same timeframe.

Today, he lives his life sitting in a wheelchair after a train accident when he was 13 years old.

The security guard for Georgia Tech and UGA and father of two, remembers his devastating past like it was yesterday.

“The only thing I can remember is her hugging me, telling me she loved me and there was nothing in this world that can keep us apart.”

Allen sits inside the exposed-brick walls of the Southern Center for Human Rights downtown next to his aunt Vanessa, who helped raise him.

His right forearm rests on the side of his wheelchair – his sleeve is pulled up, exposing a large “John 3:16” tattoo—a Bible scripture that states:

“For God so loved the world that he gave his one and only Son, that whoever believes in him shall not perish but have eternal life.”

He grew up going to church since his mom was devoutly religious.

Now, he prays that he will get to have his mom home with him, his daughters and the rest of their family for good.

“Man, every day, every day. It’s hard not having her here you know? The stuff mothers give you, I wasn’t able to have that. The time where it counted the most, I wasn’t able to have that,” he said.

“She was just this loving person you couldn’t help but love…not an evil bone in her body,” he said about his mom. “She is innocent…and I believe in her…and I want her home.”

And now, he waits.

And she waits… from inside those walls, to learn her fate once again.

Her motion hearing for a new trial was in May 2018 in Ware County. Along with Denton, Loudon-Brown waits on a decision from the judge.

Loudon-Brown filed a post-hearing brief on Nov. 15. The prosecution has until Dec. 15 to respond.

Editor’s Note: We reached out to Dr. Thomas David, however, he did not return our phone calls for an interview.