Like a rag doll

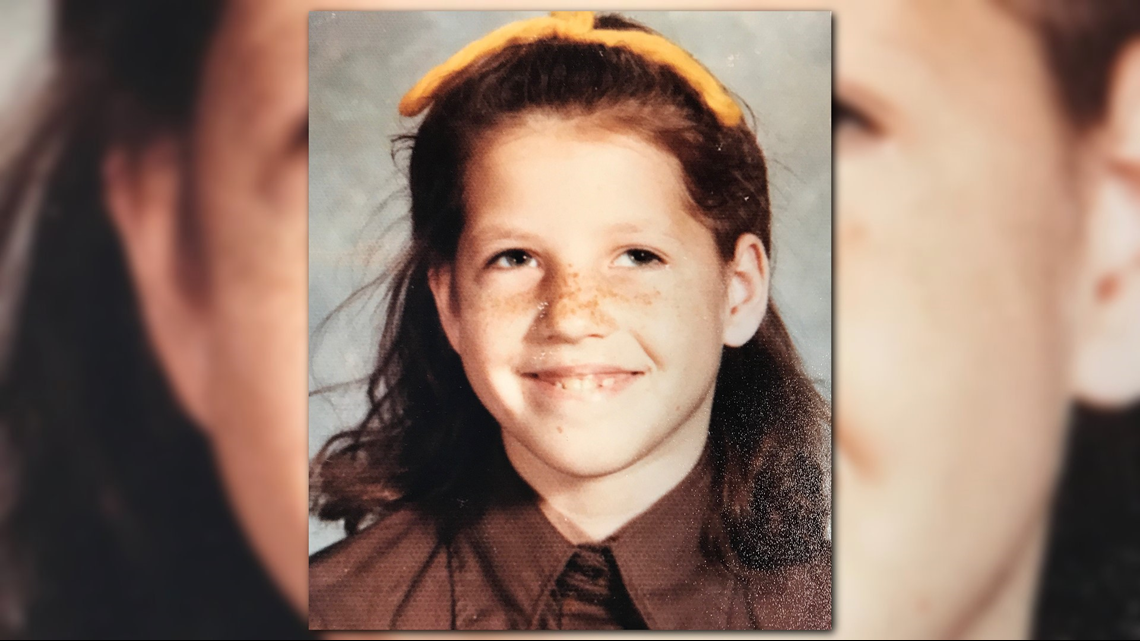

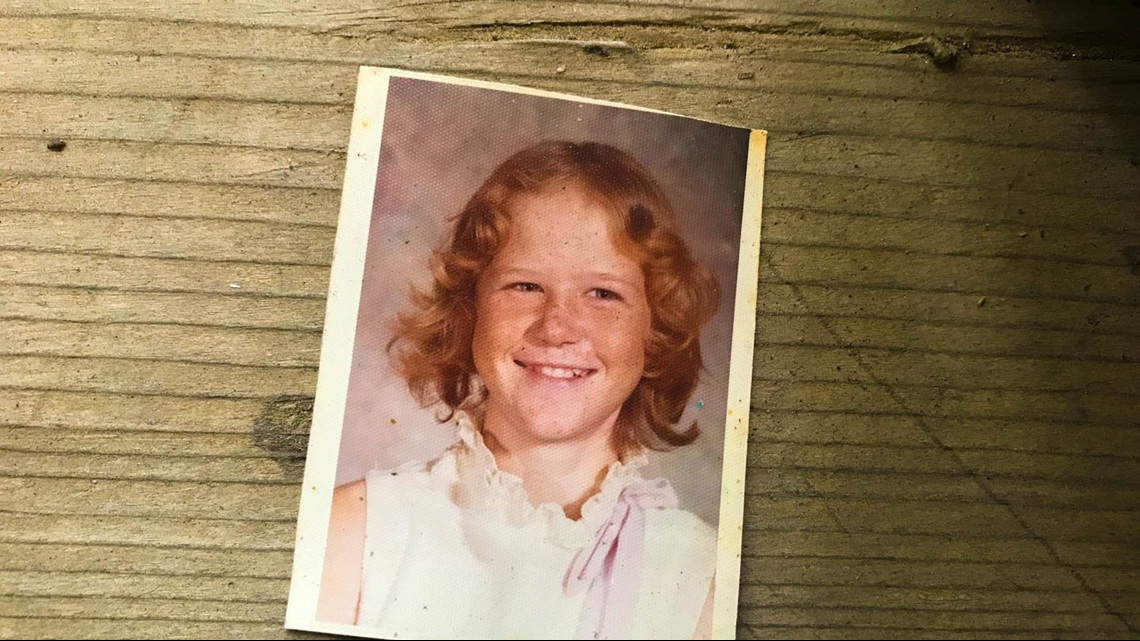

MARIETTA, Ga. – Freckles dance across Debbie Lynn Randall’s porcelain-like nose, leaving a trail from cheek to cheek. Her shoulder-length, brown hair is pulled back with a floppy yellow bow, exposing her green eyes and timid smile.

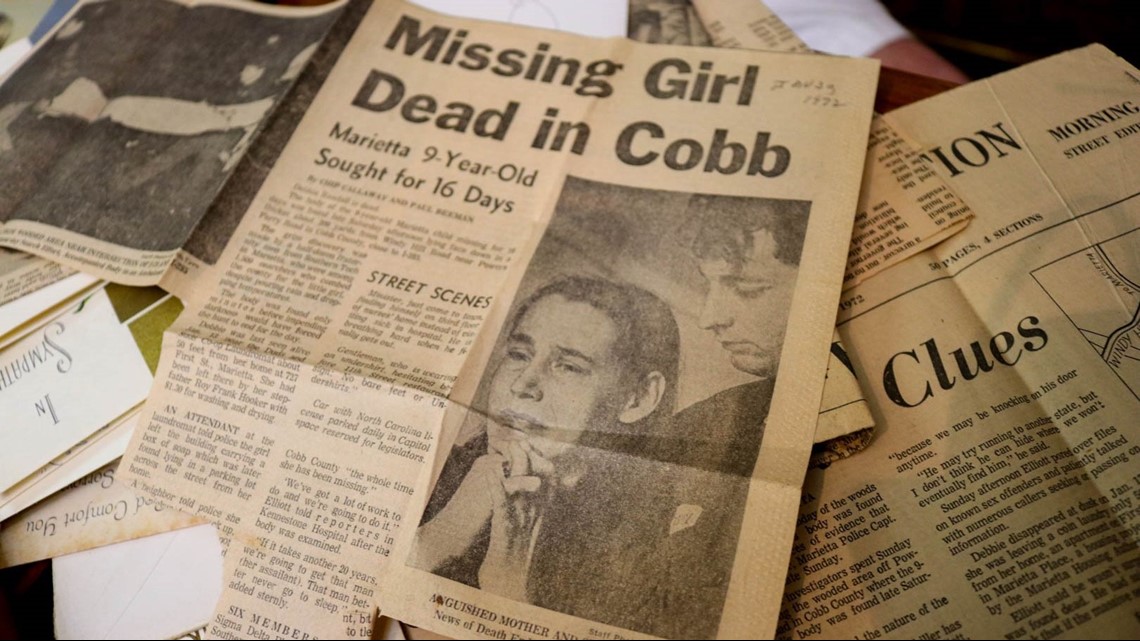

Although the brown, wrinkled collared shirt she dons in her third-grade school photo has faded, the memories of her unassuming face plastered throughout Cobb County in 1972 on missing posters are still vivid for many in the community.

Debbie Lynn loved playing with her dolls; she was the “queen” of her neighborhood baseball team; and she loved collecting and stacking soap boxes at the neighborhood laundromat across the street from her apartment building.

But in January 1972, that’s where the 9-year-old holding a box of detergent was snatched from the street, brutally raped, murdered and tossed like a rag doll into the woods.

“When Debbie took her last breath, she was looking into the face of a monster,” said Morris Nix, a detective with the Cobb County Cold Case Unit.

Her “monster” remains elusive and her family, a witness and a dogged cold case detective are determined to reveal his identity 46 years later.

“Why not let it go? All my cases are personal to me. This one is very personal to me. This was a very innocent, sweet little girl,” Nix vowed nearly five decades later.

“I think of Debbie every day. And, she deserved justice, and it's really, just that simple.”

Dirty laundry

It’s Thursday, Jan. 13, 1972, and Debbie Lynn, a Pine Forest Elementary 3rd-grader, eats dinner with her two older brothers at 5:30 p.m. It’s a bright, sunny, unseasonably warm winter’s day and she’s eager to get outside and play. But her brothers want to watch “The Rifleman.”

Their mother, Juanita Hooker, who’s under the weather, gathers the family’s dirty laundry and asks her oldest son, Melvin Randall, and Debbie Lynn to wash it across the street at the laundromat.

Melvin, who’s also not feeling well, wants to continue watching his favorite show and so Juanita asks her husband, Roy “Frank” Hooker, to take Debbie Lynn and the laundry.

He obliges.

Debbie Lynn slips on her favorite new lavender shoes, adorned with embedded red and white beads, she just got for Christmas.

At about 7 p.m., Debbie Lynn and her step-father leave their home at 727 First St., apartment No. 2., at Marietta Place, and walk the 300 feet across the street to Duds & Suds laundromat at First and Third streets.

He carries the heaping pile of dirty laundry and Debbie Lynn totes a box of Silver Dust laundry detergent with both arms.

Frank throws a few loads of clothes into two washing machines and slings a scoop of detergent into each. He sits the box of detergent down and gives Debbie Lynn $1.30 in change to operate the machines once those loads are finished.

He leaves her at the laundromat and returns to the apartment.

Debbie Lynn, who regularly takes her Barbie dolls to the laundromat to play with other girls, is without her dolls in tow this time. She picks up the laundry detergent and pushes open the front door at approximately 7:15 p.m., and saying, “Bye!” to some girls who are folding their laundry at a table inside.

When Debbie Lynn doesn’t return home to ask for help with the laundry, her family begins looking for her just after 7:30 p.m.

It’s becoming dark outside.

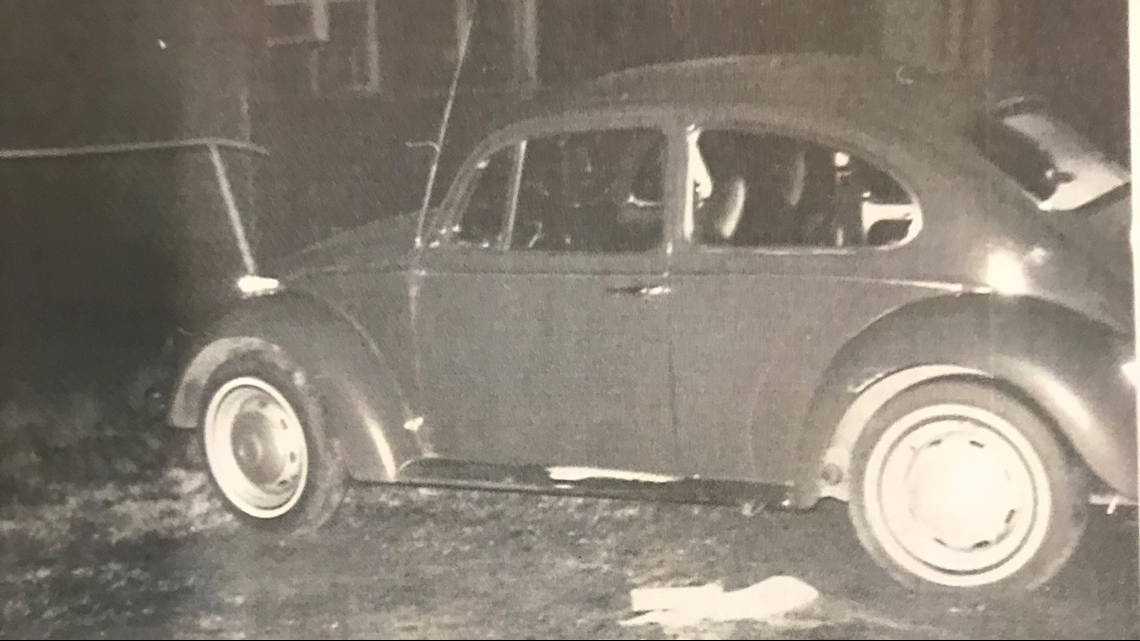

A frantic Juanita and Frank discover a spilled box of detergent on the ground next to a Volkswagen parked on First Street—approximately 85 feet from the laundromat door.

At 9:40 p.m., Juanita reports Debbie Lynn missing to the Marietta Police. That’s when police find small fingerprints on the Volkswagen’s door at a downward angle.

And Debbie Lynn… is gone.

Little girl gone | This is her story

(Click on the full screen icon next to the magnifying glass on the bottom right, to experience the full-sized graphic novel below.)

Little girl found | A 1970’s investigation begins, sans DNA testing

Police begin interviewing potential witnesses to Debbie Lynn’s disappearance.

Sandra Moody, who lives on Fourth Street, recalls a sunny, blue sky that day.

The 12-year-old strawberry blonde, who dons a sea of freckles, is helping her friend carry a large sheet-full of laundry down the hill to Duds & Suds when she sees Debbie Lynn being ripped off the street.

She describes a man, wearing a white T-shirt, blue jeans and dark work boots, grabbing Debbie Lynn by a nearby tree and throwing her over his shoulder.

She’s punching, kicking and yelling, as he rushes her to his dark pick-up truck—possibly a 1957 model with a short bed and long nose. The truck is still running when he throws the door open and hastily shoves the young girl inside.

Sandra, a self-proclaimed “street kid” herself, screams at the man as he almost runs her and her friend over.

“Slow down! There’s kids out here playing!”

But the man barrels down the road toward Fairground Street, and Sandra makes brief, but bone-chilling eye contact with him in his rear-view mirror.

She looks at her friend as they cross the road and says, “Did you see that? That man just grabbed that kid!”

She assumes that the little girl is in trouble for something.

***

Carol Clayton, 13, who lives next door to Debbie Lynn, tells police that while standing in her doorway, at apartment No. 1, between 7-7:15 p.m., she sees a dark-colored, pick-up truck driving past her Marietta Place building.

She eyes a white man with medium-length, dark hair, stop in front of her door momentarily.

Admittedly, it’s dark and she relents that she doesn’t recognize him. At first, she thinks it might be her uncle, but after watching him back his truck into a parking spot next to a Volkswagen, she realizes it’s not her uncle and turns around and goes back inside her apartment.

***

Morris Wells, who lives on nearby Sixth Street, conveys to police that on his way to Kennestone Hospital to visit his sick wife, a dark-colored, pick-up truck nearly crashes into the side of his car while driving erratically along Aviation Road.

He believes it’s an older-model Dodge truck, possibly blue or green. He notices a white man, approximately 30 years old, with dark hair, wearing a light-colored shirt, driving the truck. He also sees a little girl, between 5-10 years old with dark hair, in the passenger seat, fighting with the man, who appears to be holding the girl by her left ear.

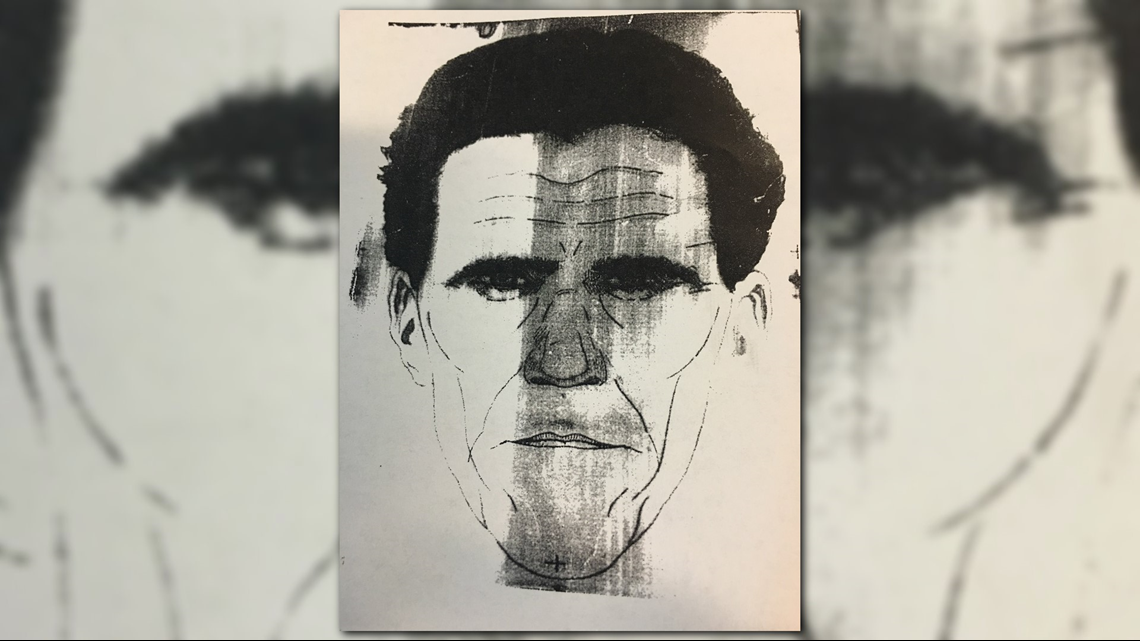

Based on witness statements, police create a sketch of their suspect and begin their search for not only him, but for Debbie Lynn.

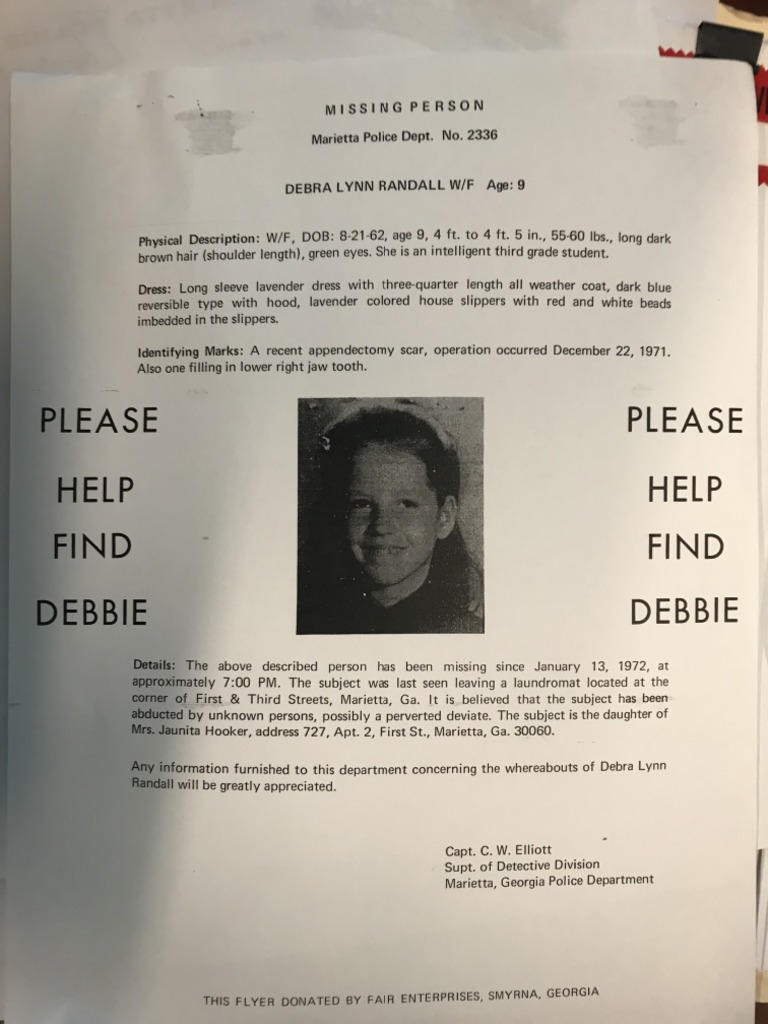

Police describe her in a missing persons flyer as, 4’ to 4’5” tall and 55 lbs., with dark brown, shoulder-length hair and green eyes, with an appendectomy scar from a Dec. 22, 1971 surgery—including that, “She is an intelligent third grade student.”

After speaking to several dozen friends, family members and witnesses throughout Marietta, an all-out search in Cobb County is placed through the Marietta Police Department, the Cobb County Police and the Cobb County Sheriff’s Office.

“Several days went by and the search seemed fruitless,” police note in their report.

On Jan. 29, 16 days after she disappeared, the Cobb County Civil Defense welcomes search parties from several parts of the state, totaling approximately 4,000 people.

It’s a chilly, rainy day.

At approximately 1 p.m., Mike Makohon, a Southern Tech student, who had just returned from the Vietnam War, joins the extensive search party, along with another student. Together, they search a heavily wooded area, between Windy Hill Road and Fox Hills Subdivision on Powers Ferry Road.

Four and a half hours later, Makohon discovers drag marks on the ground, leading to Debbie Lynn’s lifeless body, about 150 feet into the woods off Powers Ferry Road—approximately six miles from her alleged abduction site.

She is fully clothed, wearing a long-sleeved lavender dress with small yellow flowers and tiny green leaves, and a dark blue, reversible three-quarter length, all-weather, hooded coat zipped all the way up to her chin.

Her feet are encased with tiny bobby socks, however, the lavender shoes she was last seen wearing, are nowhere to be found.

Her small body is taken to Kennestone Hospital where Dr. Larry Howard, with the Georgia State Crime Lab, examines her.

Howard determines that she was suffocated, most likely by the perpetrator using her coat to cover her face, in an effort to muffle her screams. He also surmises that she was violently raped.

Dark-brown hair found on her body is sent the crime lab and tested. It’s determined to be from a white male, approximately 18-30 years old. Howard estimates that the man could have a dark complexion.

Further, a geologist studies the dirt on her clothing, who determines that the type of dirt was a north Georgia clay from within a 10-mile square mile from Cobb County and the second dirt sample is identified as clay from Dixie Cast and Stone Company in Marietta, located on Powers Ferry Road—just over three miles from where Debbie Lynn’s body was found—giving investigators a third crime scene.

A tortured lifetime remembering

Sandra Moody Walker, now-58, is haunted by what she witnessed that January day in 1972.

Sitting on the front porch of her sister’s country home, wind chimes sing in unison to a calming breeze that pushes its way through the front yard’s lofty Evergreens.

Moody Walker, a mother herself, recalls the day that changed everything—and with that memory, she is flooded with guilt.

As tears stream down her cheeks, she swiftly brushes them away with both hands before they can settle deeply within her weathered face.

“I was always out in the streets and I always felt like it should've been me,” she said, as the gentle wind turns to rain, saturating the pine needles littering the front yard in front of her.

One of 11 children, Moody Walker had moved to Marietta from a rural four-room cabin in Hazlehurst, Ga., when she was 7 years old. By that time, her siblings were grown, and it was just her and her mom. Marietta was quite the metropolis compared to the dirt roads she called home in Jeff Davis County.

But it’s that rural upbringing that made her stand up for others, she said. In Debbie Lynn’s case, however, she still wishes she could have done more to help stop what happened to her.

“I kept thinking, if it had been five minutes—if I had been even two minutes earlier, I could've stopped him. That's the way I felt and that's the way I've always felt—because I was so mean. I mean, I really was mean, not to the point where I was a bully to other people, but I did not allow anybody to pick on anybody or hurt anybody. That was just me. I grew up in the country and that's the way it was. If somebody's in trouble, you help them. And that's the way it was.”

“I could've stopped it. I would've stopped it. Even if I would've took her place, I would've stopped it.”

While she said she didn’t know Debbie Lynn personally, a part of her has always been with her.

“I've carried it all these years. This whole day has been embedded in my head. It had a big effect on me—more of an effect than I realized. Because I've never forgot it.”

“It’s always here,” she said, pointing with both middle fingers to her temples recalling the nightmares.

She relives nearly every night that replay that day over and over.

“I see her getting kidnapped. I want to chase the truck. I want to chase it; I want to stop it, jump on the truck.”

To this day, she wants justice, but realizes that with as many years that have past, the man she saw snatch Debbie Lynn could be dead.

“If he’s gone, I feel he’s busted hell wide open,” she said.

A father’s plea to heaven, a mother’s cry for answers

John Randall slowly opens the screen door at his Austell, Ga., home.

The T.V., in the living room is loud, as he shuffles to the dining room table with the help of a walker. On the dining room table, his Korean War veteran sits next to a small white pouch labeled, “Pop’s First-Aid Kit.”

The 82-year-old grandfather is grateful for the opportunity to tell his daughter’s story. But in doing so, it manifests emotion suppressed over decades—sorrow bubbles to the surface, boiling over into thoughts of revenge.

His severely worn hands carefully pull out a stack of memories: his daughter’s third grade school photo and numerous yellowed newspapers clips from a wooden box where he stores his Bible. His hands shake as he begins to unfold the brittle clippings that he has read countless times over the years, looking for clues someone missed.

They chronicle the search for his missing daughter and subsequent murder in 1972, when he was just a 36-year-old father of three.

He was working his shift at Ford Motor Company when he got the call.

“To lose your child, and in that way, and be at work on the line and have somebody come down and say, 'You need to call home.' And that's all they told me.”

The rest of the night, he said, was a blur.

Tears already welling up in his milky, blue eyes, he grabs a tissue from a box on the dining room table.

“Someone took my baby. It tears you up, literally, tears you up. I was like a zombie around here for a while. It's just like taking a big chunk out of your body,” he said. “When I found that out, it was just like losing a part of me, being gone. It was gone. And it ain't never come back, and never will come back.”

"It's a lonely world when you love someone like that for [nine] years and then lose them."

“It's more than I can take at times. I hurt so deep inside,” he said, proudly holding up a gold picture frame with his three children smiling back at him. The glass’s reflection reveals his quivering lip, smiling down at the captured moment of happiness frozen in time.

Thousands turned out to pay their respects during her funeral at Roswell Street Baptist Church in Marietta. Following a nearly citywide-attended ceremony Debbie Lynn was buried at Kennestone Memorial Park cemetery.

“She's not out there in that cemetery, I know that. Her body's there, but her soul is gone from there. She's not there. I don't visit the grave much now,” John said.

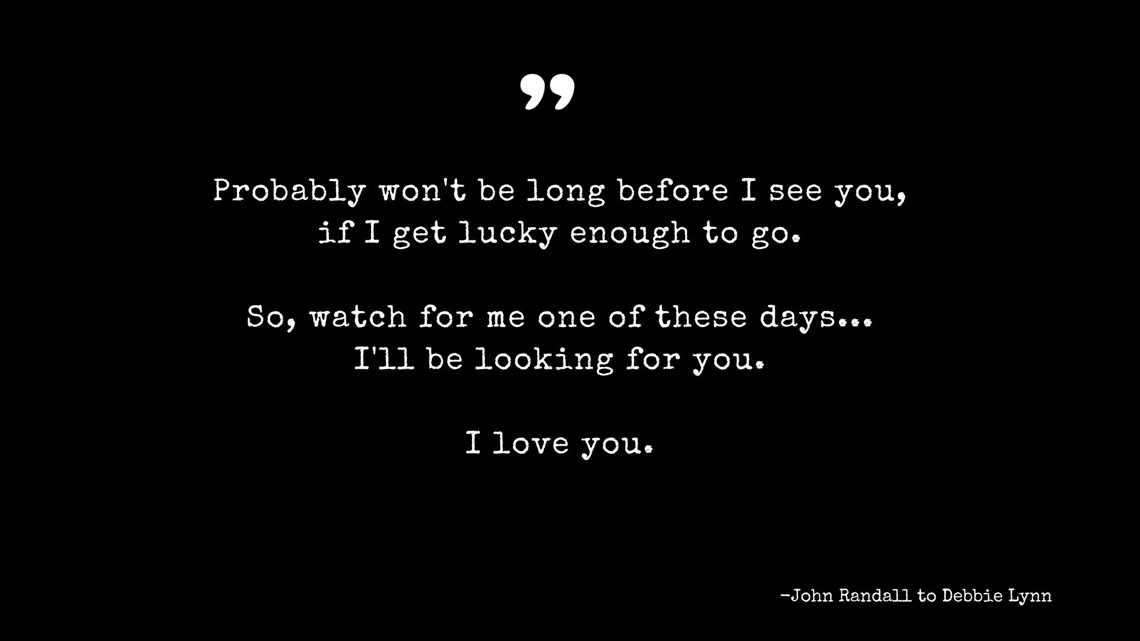

He looks up with emotion filling his eyes, and begins talking directly to Debbie Lynn, as if she was sitting at the other end of the table.

“I love you. I did the best I could raising you. I know I wasn't the best father in the world, but I tried to raise you right, and you minded most of the time like all kids do. But you were a good kid, and I love ya. I have love in my heart for you. I'd give anything if I could see ya. Probably won't be long before I see you, if I get lucky enough to go—which I hope I am. I look forward to it. I'll try to catch a glimpse of ya as I go by, wherever I'm going. So, watch for me one of these days... I'll be looking for you. I love you. Goodbye.”

He pauses, then blows his nose and wipes the tears from his now-bloodshot eyes.

“I still love her today. I don't have her, but I still love her today. And she is my baby,” he said, swiping his nose with a tissue in between sniffles. “I miss her; I love her; and I'll never forget.”

And like so many times before, he gathers the photos and clips one by one, looking at each again as he tucks them neatly back into the wooden box, on top of his white Bible, perhaps for another four decades.

“I don't know that I'll ever find out. But I still have hope in my heart for her,” John said about finding out who the person he dubs a “maniac” was who ripped away his youngest child.

“The person who done it, I'd like to believe that he was already dead, but I'd like to believe that he would suffer for the rest of his life. I would love for him to suffer—because I know he made her suffer.”

He believes that it was someone who knew Debbie Lynn and he prays that someone who knows will come forward.

“I think that's about the only hope I've got is to have somebody read or see this interview... there's gotta be people out there that still know about it and still care about it,” he hopes. “I think that somebody that knows about it will be able to come forward, maybe, and get that person off of the road before he does it to some other family.”

And he wants more than jail time for the culprit.

“Whoever he is, he needs to be put to death. I believe in the death penalty for somebody like that. They're not sorry they done it, or they would've already come forward,” John said.

Time moves on with an endless cycle of birthdays and holidays to celebrate each year. But for the Debbie Lynn’s family, there’s not a year, nor a day that passes that she isn’t in their thoughts—missing her.

She would have been 57 years old.

Her mother, Juanita now-Wheeler was 31 when Debbie Lynn vanished. Soon after, she left Marietta and made her home in Centre, Ala., along the “Trail of Tears,” just on the other side of Floyd County, Ga.

The still-grieving mother spoke to 11Alive’s Jessica Noll in July, in a soft, feeble voice over the phone.

Each breath, each word is a struggle as she coughs between sobs remembering her only daughter.

“She was a sweet little darling,” the 78-year-old battling leukemia said, taking a long pause to breathe between thoughts.

“She was my baby and I loved her so much. I couldn't understand why it was her instead of me. It was the way she had to go that hurt me so bad. And it still hurts. I would at least like to know who done it before I pass away.”

But she would never know.

Wheeler died on Sept. 17, 2018 waiting for answers.

Her final wish was that her ashes be buried with Debbie Lynn.

Thawing a cold investigation

Nix cannot see a Barbie doll without thinking about Debbie Lynn.

He was just 19 years old when her murder shook his hometown.

“I came in the house. It was on the news and my mom was wringing her hands. I could tell something was really wrong, and I said, 'What happened? What's wrong?' And she started giving me a little bit of the details and I could tell it really frightened her—because that was not something we were used to at that time,” Nix recalled.

“It crossed every line within the city; people were afraid, they were angry. It was frightening, because at that time, in 1972, we were still a bedroom community to the city of Atlanta.”

He has since had a long career in law enforcement and criminal investigations, but he has never forgotten her story.

In fact, for the past three years, he has been relentless in his pursuit to solve her case. During his time investigating, he has made progress.

Nix has eliminated suspects, however, he has not been able to zero in on a definitive person of interest… yet.

“I still think that it's possible to solve this case. It's gonna take, I guess you'd call it a miracle. It's gonna take a huge break, but we've come a long way from where we were. And I do think we have a chance to do this. Still a lotta work to do, and we're gonna do it,” he said with confidence.

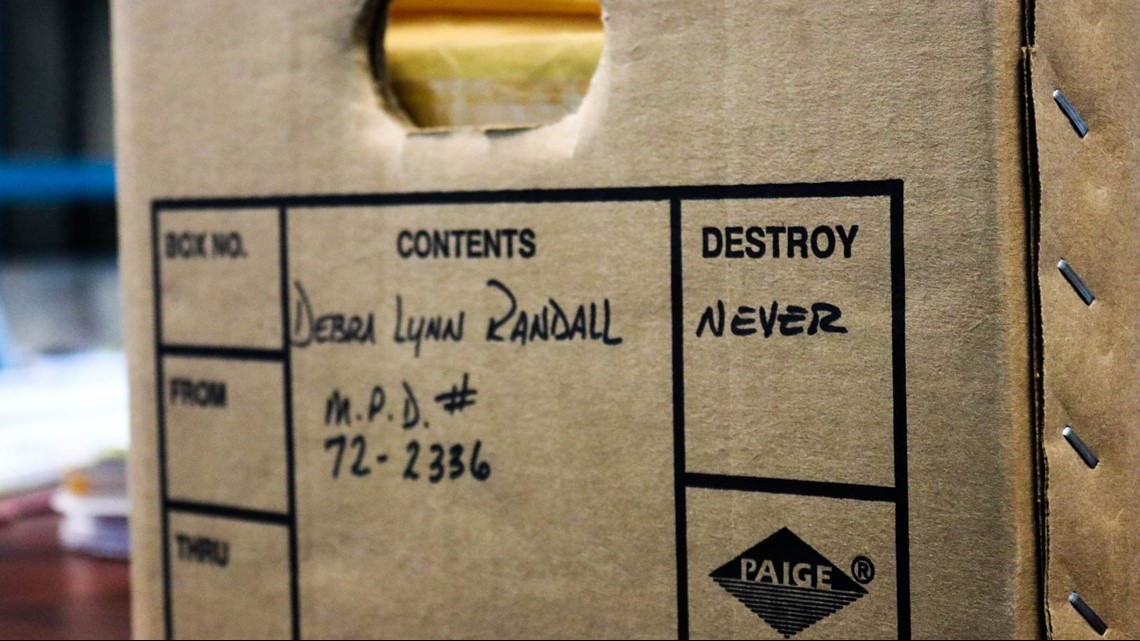

Nix pulls a tan, cardboard box over to him on the conference table inside the Cobb County Cold Case Unit’s office. In bold, black letters on the side, in a black square, labeled “DESTROY” is the handwritten word: “NEVER.”

It’s Debbie Lynn’s case file and entails every gruesome detail of her rape and murder.

“The assault upon Debbie was brutal. It was vicious. It was inhumane,” he said cringing as he holds some folders up from the box.

The retired, now-volunteer detective begins pulling the box’s contents out, including a slim file folder with a black and white photocopy of her school photo paper clipped to the inside cover—reminding him each time he opens the file, who he’s fighting for.

“When I first got this, first thing I thought, ‘Wow. There's not much here.’”

Much like her father, Nix agrees that Debbie Lynn likely knew her attacker.

Now, DNA is going to be the one thing that can definitively ID her assailant, or as Nix refers to him as “her monster”—something that wasn’t available when she was killed.

In 2016, Nix was able to obtain a DNA profile from the evidence that Marietta Police collected and kept from her case. That information indicated that there was only one perpetrator who assaulted Debbie Lynn in January 1972. And from that, he has been able to eliminate quite a few persons of interest from his radar.

In May 2018, Nix believed he might have the “monster.” But a run through the national database, CODIS, proved that the DNA did not match any known offenders within the system.

“We had three or four people who looked like really, really good suspects. And we spent a lot of time an effort, but we managed to eliminate them. So, I think we've come a long way, but, we've got a long way to go. And, we do have things to do. I mean, we're not at the end of the road,” Nix admitted.

The dogged detective plans on retracing patterns of assault and arrests between 1973-74 throughout the southeast to try and match crimes to Debbie Lynn’s case. A daunting task at best.

“People die, records are missing, and it's difficult. But, we did get a DNA profile. So, if we can ever match it with someone… Game over.”

There is, however, the possibility that his suspect was never arrested for another crime or did not commit a crime after DNA testing was possible, and therefore would not be found in CODIS—which was not a nationwide database until 1994.

“I think it's very possible he was never arrested, or, that he took a break for whatever reason. Perhaps for years. This type of injuries that were inflicted, I have wondered, was this rage? What would set someone off to do this? And, so, I don't know if it's part of his perversion, or if he was enraged over something.”

Based on his investigation, however, he said he has a pretty good idea of at least the type of person who committed this crime.

Nix believes that he was low- to low middle-income and possibly a construction worker or worked at Dixie Cast and Stone based on the truck he drove, as well as the dirt samples found on Debbie Lynn’s clothing. And it would have been an ideal spot for seclusion.

“I spoke to the owner of Dixie Cast and Stone, and he told me back in the day, he said, ‘That would have been the perfect place.’ He said, ‘You could’ve taken her back there around the sand pits, and nobody would have ever heard her.’”

As someone who grew up in Marietta, Nix said, he didn’t even realize that the isolated drive to the sand pits existed.

“He could have driven down that road, right behind those sand pits, and no one would ever see him. But, he would also had to have known it was there. He didn't just stumble upon it. So, if he took her there, he knew it was there.”

Nix knows her case and the route to her gravestone at Kennestone Memorial Park cemetery like the back of his hand. He visits her often, promising her that one day her killer will be found.

“When my time comes to end it, I'm going to pass it on to somebody else. For me, personally, it's not about an arrest, it's not about a conviction. It's about closure for the family,” Nix said, standing at her marble, gold-embossed gravestone, adorned with a vase holding a colorful bouquet of artificial daisies.

“I think if we ever come to a resolution on this it's going to be because somebody [coming] forward. I think we've got a great chance on this. It's a long shot. I mean, you have to be realistic. It's a long shot, but it's a shot,” he said.

It may be a long shot, but it’s not the end of the road for Nix.

“Debbie's case was not just a molestation, and assault case, whoever was involved with this, is a psychopath. And, a lot of people have said to me over the years, ‘Why don't you let it go?’ There's newer, other cases that we can work on, but, I just don't wanna let it go ‘til I know that we're to the end of the road, and we're not to the end of the road.”

If you have any information about Debbie Lynn Randall’s case, call the Cobb County Cold Case Unit, at (770) 528-3032 or email them at coldcase@cobbcounty.org.

HOW WE DID THIS STORY

Gone Cold is an ongoing series, where 11Alive Journalist Jessica Noll investigates some of the most infamous and lesser-known cold cases in Georgia. She's digging for answers for the still-grieving families who long for them, and for the victims who have never found their justice.

11Alive Journalist Jessica Noll spent months interviewing law enforcement, witnesses and family members to journalistically gather every aspect of the story possible. She investigated the case, sifting through public records, police reports, renderings and photos. She also visited each crime scene associated with Debbie Lynn Randall’s case.

This story is written in a narrative-style, long-form and was methodically reported in order to obtain each detail of this 46-year-old cold case, in an effort to reveal what happened leading up to his disappearance in 1972, when she was snatched from a Marietta, Ga., street, raped, brutally killed and tossed like a rag doll into the woods.

Additionally, we chose to tell her story in the form of a graphic novel, in which she is portrayed as a doll and her perpetrator is depicted as a monster. After nearly five decades, her case remains unsolved and through an innovative form of digital storytelling, we hope to reach a broader audience—because one of the only things standing in the way of closing a case file for good, is someone knowing something, seeing something and saying something.

The Doll and Monster graphic novel is written and reported by Jessica Noll and illustrated by Amanda Wood.

CONTACT THE REPORTER |

Jessica Noll is a multimedia journalist, who focuses on in-depth, investigative crime/justice reports for 11Alive's digital platforms. Follow her on Twitter @JNJournalist and like her on Facebook to keep up with her latest work. If you have a tip or story idea, email her at jnoll@11Alive.com or call, text at (404) 664-3634.

Join our "Gone Cold" Facebook group and join our discussions about cases like these, at https://www.facebook.com/groups/gonecold/ and follow us on Twitter: @11AliveGoneCold.