WARNING: Some of the details in this story may be considered too graphic for some audiences.

Lived to tell

ATLANTA – The man’s knee presses tightly against Susan Drew‘s chest, sliding into her throat—his rough hands grasp her neck, squeezing until everything turns black.

Just seconds prior, the rolled-up windows fog from her muffled screams and ongoing struggle to push the man off her. As her white- and yellow-striped, spaghetti-strap sundress rides up underneath her, she begs and pleads for her life—desperately kicking him with her white Keds.

“Help me! Somebody, please God, help me,” she thinks to herself, but knows no one will hear her.

The 20-something prostitute doesn’t know his name. To her, he’s just a “John.”

In what she believes to be her final moments, the last thought that flutters through her consciousness is her children and the legacy she is leaving behind.

She’s considered one of the lucky ones, who did not make the list of strangulation homicides between 1993-98 in metro Atlanta, when more than 40 other women would not be able to escape the killer(s)’ grip, in a time of tremendous growth surrounding the 1996 summer Olympics.

And while the Olympics unarguably put Atlanta on the map, decades later, investigators are looking back at a different map, pinpointing murders—more than half still unsolved—that could suggest that the metro area had one or multiple serial killers in the 1990s.

‘Living to die’: Surviving the streets and the strangler

It’s rush hour and a now-46-year-old Drew talks about her life, and more importantly her former drug-addicted life on the streets, for the duration of the drive from her rehab center in DeKalb County to downtown.

It’s dusk and traffic is bumper-to-bumper and it takes nearly an hour a half to get to her old stomping grounds, Cleveland Avenue.

Street lights and bright red taillights barely illuminate Drew’s face. She fades into the shadows as she relives the worst time in her life.

Cleveland Avenue is admittedly her least favorite place in the world—but it’s also a place that reminds her of how far she’s come, and how hard she works every day to stay clean and stay away from her past that nearly killed her.

And just like that, she’s immediately transported to her most vivid memories of the 1990s turnstile of drugs and sex for money.

The Hunt: Inside Susan Drew's streets

“A lot of it didn't seem real. Nothing in my life seemed real at that time. Nothing. I was living to die. That's what everybody out there's doing. This is a life sentence. These streets up here, is a life sentence.”

And she almost did… three times.

“Is this guy gonna kill me; is this guy gonna kill me?”

It was a fluid thought that penetrated Drew’s mind every time she got into the car of a “John.”

She explains from Cleveland Avenue, when a “John” wanted to pick her up, he would drive slowly past her, then before hitting the hill, she said pointing up, they would tap their brakes—lighting the way with an eerily dark red glow to his car.

Standing on the dimly lit street, her past comes fully into focus when a car passes her slowly; the driver taps the brakes and exposes Drew’s weathered face and deep brown eyes, before making it up the hill.

A mother of four, Drew was raised in Peachtree City and said that she has struggled with addiction since she was 12 years old after being molested.

"I was abused as a child, but when I picked up, I started abusing myself. I carried that abuse as a child and made it the reason why I was doing what I was doing, but it's really not... I continued to abuse myself for something I had no control over."

In 1996, she was 26 years old and made the streets her home for the next 20-some years off and on.

“I've seen many things. Many things have happened to me. Rapes—too many to count.”

But number of attacks that nearly ended her life was three. She was strangled twice. And left for dead once.

In the ’90s, Drew walked Zone 3.

“They knew they had a serial killer,” she said about the police, without hesitation.

One day, she remembered, an undercover detective came to the street she frequented.

“He picked me up that day... and was like, ‘Look, there’s someone out here killing y’all.’ He would point out different areas to go to. ‘Just go there. They're killing y’all.’”

“This guy’s not gonna just hurt you, and you’re gonna go get away. You’re gonna die.”

She also recalled ambulance drivers who would drive by to warn her and the others working.

“They were showing pictures to all of us, trying to get us to go to different locations because they were killing us. They were killing these girls.”

Soon enough, she would know exactly what they were warning her about.

“A lot of it's a blur. The people are a blur. You live down there to forget—so, I stayed intoxicated.”

“We did not care. And that’s why they pick us,” Drew said of the killer or killers.

On a hot July night in 1997, nearby Lakewood Amphitheatre, a man picks up Drew in a silver, four-door sedan just after 3 a.m.—her primetime for business.

The man, who is wearing jeans and a dark T-shirt tells Drew that he’s a police officer and reads her, her rights. He pulls out a gun and points it at her face, demanding that she does what he says.

Knowing the lifestyle and law enforcement, she doesn’t believe he’s law enforcement, but fearing for her life, she relents.

As she gets into the car and closes the door, she notices that he has a gun in his lap.

Once they arrive at their destination, he moves the firearm under his seat and puts the keys in the backseat.

He then forces her to perform oral sex on him.

After she finishes, he gets out of the car and walks around to her side. She quickly rolls up the windows, locks the doors and grabs the car keys from the back.

She hops into the driver’s seat, but realizes that it has a clutch—she can’t drive a stick-shift.

But, she cranks the car enough to start it and take off—only to ram head-first into a tree. He kicks in the passenger-side window to get to her and drags her to the passenger seat, while she fights him.

“I don’t want to die; please don’t kill me; please don’t kill me.”

She feels his knee pressing harder and harder into her throat and his hands around her neck. Her words are slowly stifled; her eyes close and she slips out of consciousness.

He throws her limp, naked body out of the car.

He tosses her behind a tree.

He leaves her for dead.

For years, Drew didn't care if she lived or died, but in that moment, all she wanted to do was live.

“He left me inside those woods, behind that tree,” she points into the wooded, shadowy abyss with a small flashlight to unveil the most horrific night of her life. “He dumped me in the woods. He thought he killed me. I thought he killed me.”

As she woke up, she said, she vaguely remembers his taillights pulling away.

She got up, brushed off as much grime as she could and put her summer dress back on.

“He had strangled me to the point that I lost my bodily functions, so I was dirty and I had bloodshot eyes; I had marks,” she says clutching her own throat.

“[It] seemed like a bad dream. It was like… never-ending.”

She never called the police. And she left the scene to head back to the street for her next fix—but mostly to forget.

But it’s a day that she has never been able to break free from in her mind. And its intensity lingers years later.

“It was terrifying. You know, I lived out there... I lived out there wanting to die. But when it was happening, I wanted to live.”

“It was just evil. There was no mercy. No mercy. It didn't matter what I said. And I hated the fact that I was out there on the streets and away from my children, but when I was about to die all I could think about is, 'My God, my kids are gonna know. They're gonna know what I was doing. They're gonna know how I died.' And how humiliating for my children. Having to explain how their mother died on the streets, prostituting herself. That's all I could think about was my kids.”

Life and death on Cleveland Avenue

Drew takes a long drag off her cigarette. As she exhales, the smoke slithers through her fingers and rises in the headlights, illuminating the skeletal bone tattoos extending on each of her fingers.

A large “Carpe Diem” tattoo peeks through her crisscross-patterned shirt and stretches across her chest.

The chill in the night’s air requires layers, but “Zone 3” tats protrude from under her black hoodie’s sleeves on each of her wrists. It reminds her of where’s she’s been.

She looks around in the darkness.

She watches “Johns” slow down as they approach her.

These streets were her home.

These streets were where she made a living.

These streets were where she almost died.

These are the streets where other women lost everything—including their lives.

“You feel dirty. You feel like less than a human being—because a lot of the girls who get killed out there just get a tag on their toe. Nobody investigates where they came from, whose daughter they are, whose mother they are. You're just a casualty. You're less than a dog on the side of the road.”

It’s a January evening, and easily cold enough to see Drew’s breath as she speaks about the decades she spent outside on nights just like this. Her black capri pants reveal faded tattoos on her ankles.

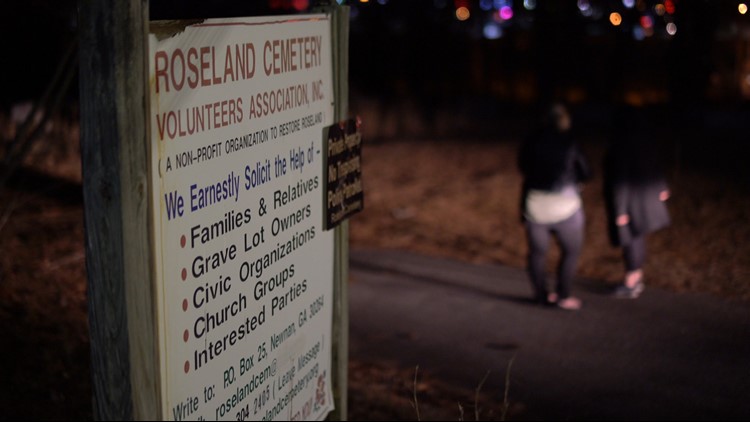

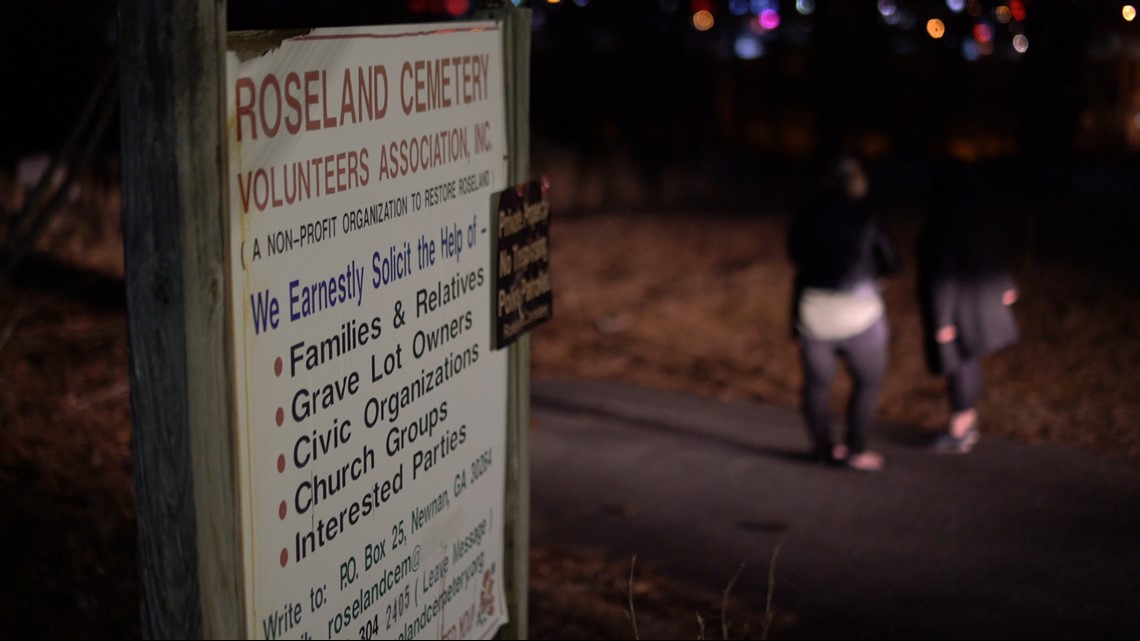

Standing inside Roseland Cemetery, just off Cleveland Avenue, it’s pitch black, backlit only by the expressway traffic of Interstate 75.

It’s where Drew brought her customers.

It’s where people buried their loved ones.

But in 1997, it was the place where one woman was taken to be brutally raped, killed and left naked, tied to a tree.

And the noise of the traffic floods Drew’s memories.

It was a life on the streets full of addiction, self-destruction and murder.

“I hate this place,” she shudders. “People were dying left and right.”

“You’re on the bottom out here. And you’re treated like you’re on the bottom – by the cops, by the drug dealers, by everybody–you’re less than human if you’re a woman out here on the street selling your body for dope.”

Inside the now-overgrown cemetery and situated and about four miles from Atlanta’s Olympic stadium for the summer games a year earlier, Drew remembers being a prostitute when the woman’s body was found inside one of her go-to spots to take her “Johns.”

“That’s where they found the girl tied to the tree,” Susan points to the black abyss of the southside of the cemetery. “She was tied to the tree to the point where she was upright.”

“This girl was beaten with no mercy,” Drew recalls.

While this murder made the headlines, Drew says, it was happening all the time around her on the streets.

“The women were dying way before then,” she says. “Many. You didn’t know. You just hoped… you would survive.”

On Aug. 19, 1997 just after midnight, Atlanta Police Officer R.C. Huffman Jr., responds to the 700 block of Cleveland Avenue.

It’s Roseland Cemetery.

Nearby a couple of headstones belonging to the names, English and Harbin, and just off a dirt road, police find a disturbing scene.

About 350 feet from Cleveland Avenue and on the south side of the cemetery, stands a 30-feet-tall oak tree—approximately 3 feet in diameter.

Attached to the tree is a nude woman’s body, with multiple of cuts, bruises and blood.

Her wrists, adorning three white metal bracelets, are restrained with cords. She’s wearing a geometric white and yellow metal ring on her left ring finger, and a Mickey Mouse ring on her left index finger, on which she’s wearing unbroken, long, fake red nails.

Her face and long blonde hair are blood-soaked, and a pair of beige pantyhose are wrapped tightly with a square knot around her neck.

While her purple-painted toenails are exposed, her body yields no identification. However, some ink on her right ankle reveals the word, “Precious,”—and that’s what police name her for the time being.

The teenager has been raped, and her cause of death is blunt force trauma to her head and ligature strangulation.

She is later identified as 19-year-old Jessica Schultz.

Jeffrey Sharp was arrested in October 1997 and indicted in 2000 and charged with malice murder, four counts of felony murder, rape, aggravated battery, aggravated sodomy, kidnapping, false imprisonment—among other charges.

While Sharp was caught, the murders continued.

The strangulations were spreading outside city limits and penetrating neighboring jurisdictions and counties.

'Hat Squad' leader haunted by the past

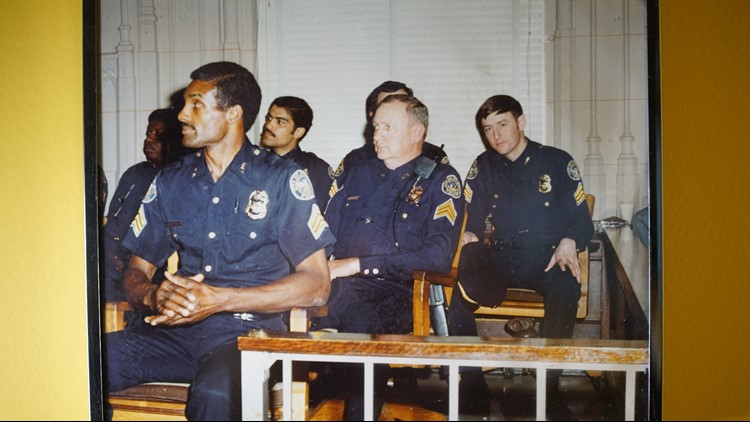

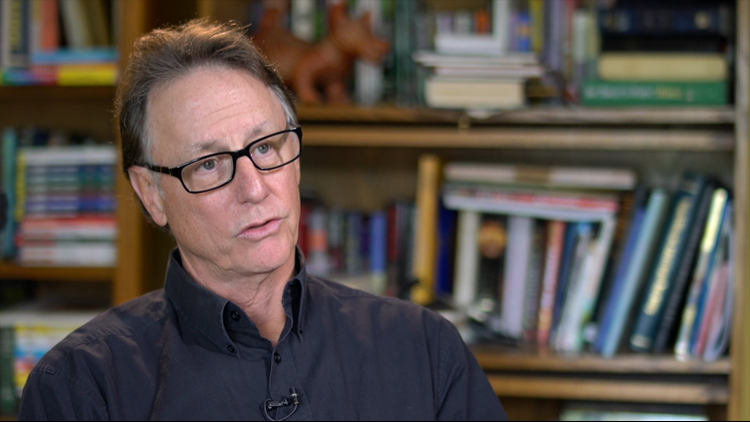

In the mid-’90s while killers or a killer was stalking the streets, APD homicide detective-turned commander, Danny Agan, doggedly worked the cases as a member of the famed “Hat Squad.”

It was his job to catch killers and his reputation around town was making an arrest “with flair.”

With a gold badge on his hip, donning a suit and tie and a fedora to match, he was part of a 22-detective homicide unit that saw an all-time high on murders—more than four a week on average, he said.

It was a 24/7-operation and, “business was good,” said Agan, who worked nearly 800 homicides—and solved approximately 75 percent.

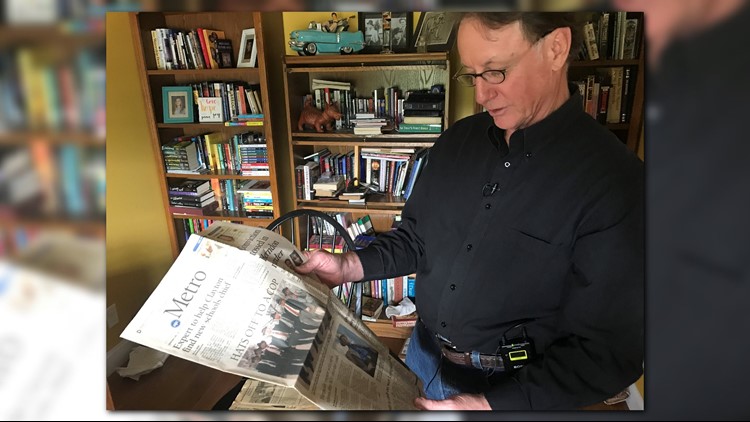

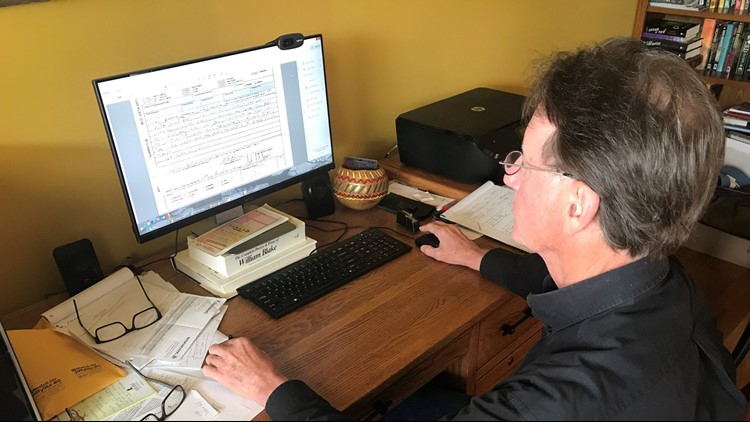

Agan, who retired in 2003, at 50 years old, to a hundred-acre farm about an hour and a half outside the city limits, said the unsolved cases haunt him to this day.

The now-64-year-old, surrounded by framed memories of his heyday in Atlanta, goes back in time to recall the most memorable and horrific cases of his career.

“You can’t solve them all,” he said with a sigh. “This is a big city and things do happen.”

And while homicides were up--nearly 200 total homicides in 1994, according to Agan--his “Hat Squad” wasn’t sure if there was one or multiple killers roaming their streets.

“I don’t think I came to a conclusion one way or the other,” he said. “You have to keep an open mind until you know all the facts. And the deal is we didn’t know all the facts back then.”

Investigators never concluded undoubtedly, that they had a serial killer in their midst. But, it also did not disprove the possibility of a serial killer.

“I don’t think we ever came to a hard and fast conclusion of [who] we were dealing with, multiple suspects or one suspect, or maybe even two suspects,” Agan said, regarding the 1990’s strangulation murders overall.

Agan was the detective in charge of several of the cases through 1995, including Brenda White, Susan Lorraine Lansford and Valerie Payton. Some were solved by cold case detectives a decade later, after his retirement.

On Dec. 6, 1994, Lansford, 28, was found under a burned-out house on McAfee Street.

“She was thrown away like a piece of garbage,” Agan remembered.

Her case was cleared in 2004 after police arrested Sherman Ridley for her death.

Three days after Lansford’s body was discovered, 31-year-old Brenda White’s strangled body was found at 2440 Cottage Grove Ave., at East Lake Elementary School, in East Atlanta on Dec. 9, 1994.

She was posed in a “proactive and shocking” way, Agan remembered. And to him, that meant, the killer was going to do this again.

“Whoever did this was sending a message,” he said, looking through her case file from his computer in his home office, where his bookshelves are stocked full of books by Stephen King and J.K. Rowling’s “Career of Evil” series.

White’s case was cleared in 2010 when Joseph Sims was arrested.

Valerie Payton, 39, was found dead in a field near Kenyon Street on Oct. 19, 1994. She had been raped, sodomized, strangled and stabbed 50 times. Her nude body was found with a hand-written note on her chest that stated, “I’M BACK ATLANTA, MR. X.”

“[The note] made us wonder who this guy is, where had he been, and of course had he done something like this before,” Agan said about the possibility of a serial killer on his turf.

“My inclination would be he’s probably good for some other murder that we’ve never connected the dots to.”

But, police at that time, he said, didn’t want to just rely on their hunch.

“Of course, the sensational story is ‘serial killer is at large, and police won’t say.’ Well, the police weren’t saying ‘serial killer’ for certain for a reason—and that’s because we didn’t know,” Agan revealed. “These were for the most part individual crimes with no identifiable suspect and we were doing the best we could with what we had,” Agan said.

The Hunt | Danny Agan's 1990s

The killer was quickly dubbed “Mr. X” for the note, as well as for leaving an “X” carved into at least one victim’s genitals.

“This is somebody that’s saying, ‘Hey, look at me. I’ve done this. You can’t catch me,’” said Agan, who started working with the APD in 1974.

It was “a horrific crime, left out in an open field where she could easily be discovered, and with this note here that almost a taunt to the police of, ‘Screw you; I’m here.’”

Agan knew he was dealing with a completely different type of offender with Mr. X.

“Committing a murder, and leaving a body posed in a provocative, shocking way – is something psychological that I can’t get my head wrapped around. But I know there’s something at play here that’s making this guy do what he’s doing.”

And a serial killer won’t stop.

“If he is in fact a serial offender, if he does it once and enjoys it, he’s gonna do it again,” he said. “They’re gonna do it. They’re gonna do it, until they get caught, or until they can’t do it anymore.”

Michael Harvey was arrested in 2008 for Payton’s murder.

He was charged and convicted on malice murder, rape, aggravated sodomy and aggravated assault in connection with a strangulation death.

While three witnesses testified to similar experiences with Harvey, he was only convicted of Payton’s murder—although in his appeals, he maintains his innocence.

In the same month and year that Shultz was murdered, Bernita Tolbert’s body was found in an overgrown lot at 500 Fair St., in southwest Atlanta in 1997.

In May 1995, Wanda Dell Daniel’s strangled body was found on Pine Street near Marietta Street in northwest Atlanta. It remains unsolved.

Also, in 1995, the APD created a female homicide task force specifically to look at these cases, and to gather information that might connect the dots.

During those investigations, the task force looked at characteristics that could link the homicides, including:

- Females found in vacant houses / buildings

- Females found near school property

- Females strangulated

- Females nude or partially nude

- Bound

- Known prostitute / drug users

- Signs of sexual assault

- Geographic areas

- Age of females

The APD Homicide and Intelligence Units looked at six cases as possibly being related, which included the White, Payton, Lansford cases. However, their cases were closed with three separate arrests.

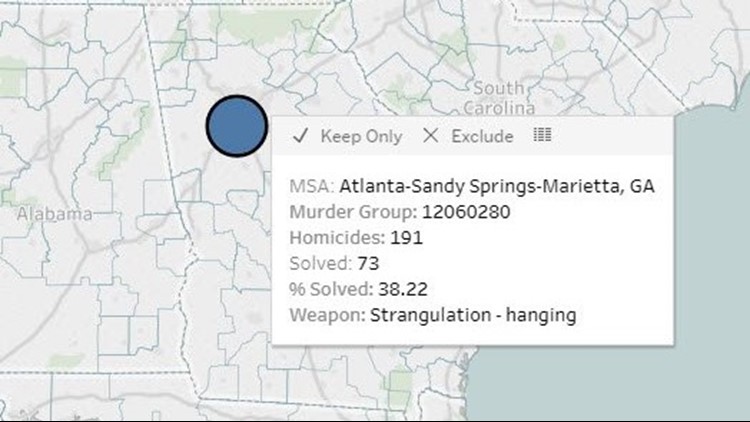

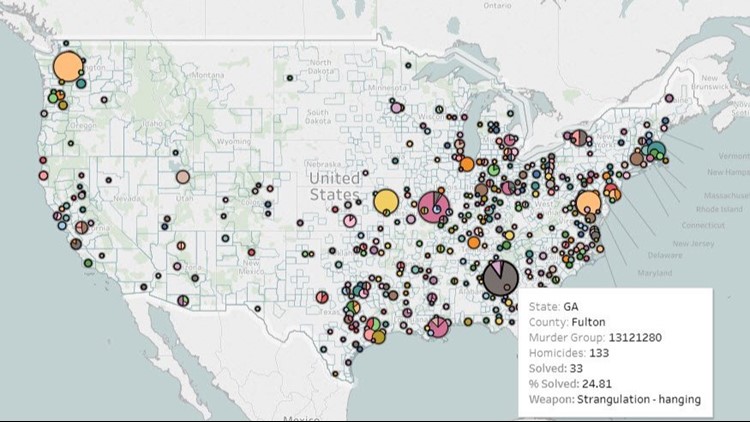

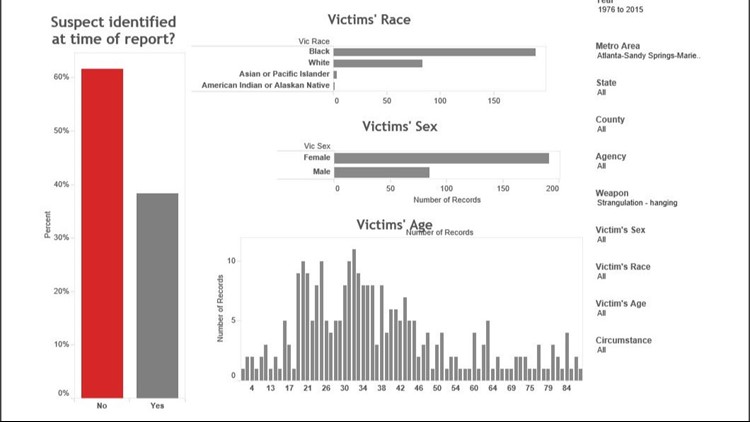

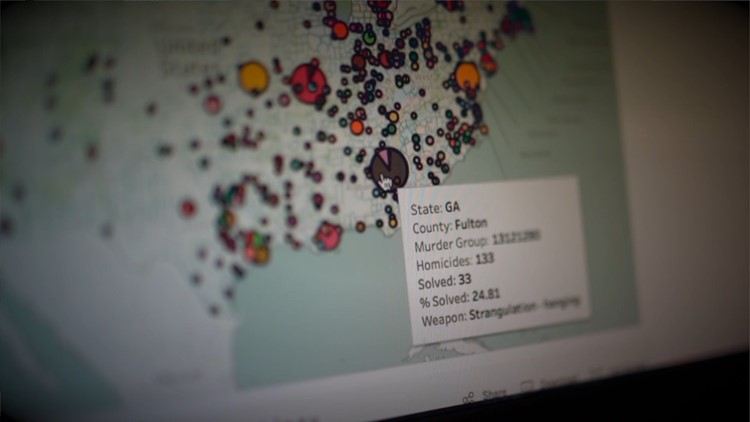

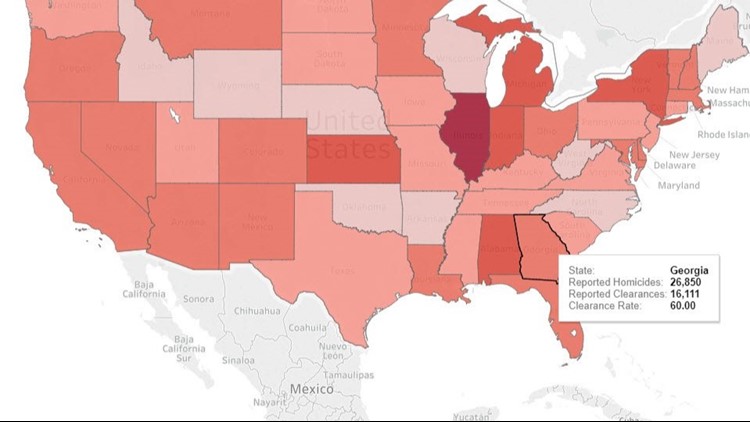

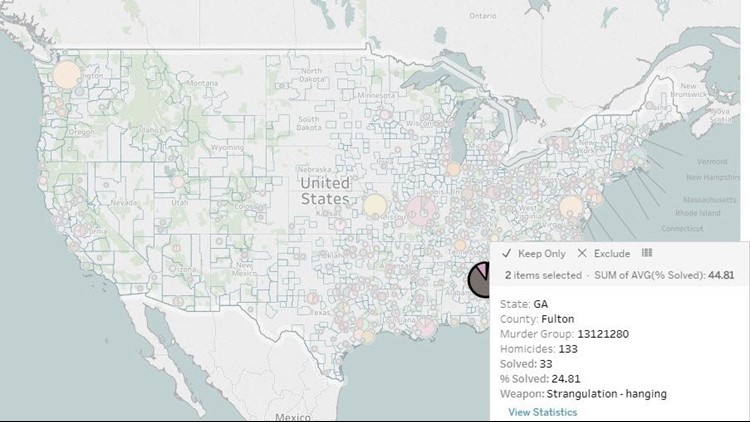

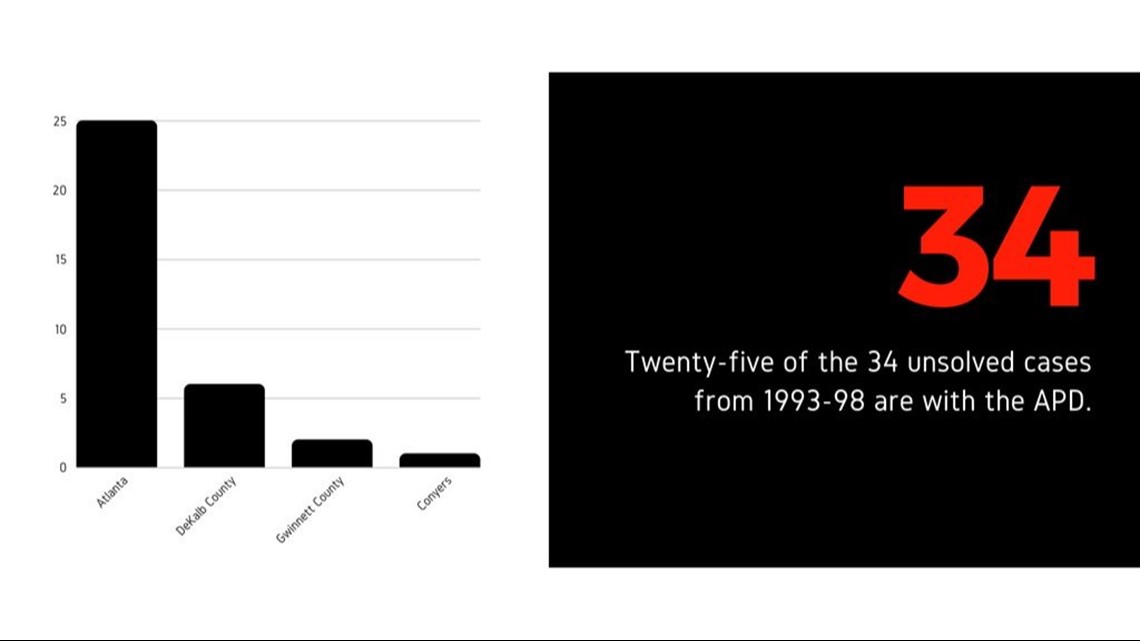

According to the Murder Accountability Project (M.A.P.) database, there were 40 females strangled or killed by asphyxiation between 1993-98 in metro Atlanta, including surrounding counties--as well as outside the prostitution ring.

The FBI Uniform Crime Report (UCR) data shows that only six of those were reported by local police departments as solved.

As indicated by M.A.P.—which collects, maintains and updates the homicide numbers all over the country—34 of those cases, including in 25 in Atlanta, six in DeKalb County, two in Gwinnett County and one in Conyers, Ga., have gone cold for the past two decades.

Both female strangulation murders in Walton County in March 1993, and in Gwinnett County in June 1998, 23 and 35 years old respectively, were solved.

The FBI’s uniform crime report specifies that the Atlanta Police Department is responsible for 29 of the 1993-98 cases—25 of those unsolved.

However, according to Carlos Campos, APD’s director of public affairs, since the FBI’s numbers were released, the department has closed a total of 13 of those cases, giving them a 44 percent clearance rate on strangulation deaths during those years—many solved by the department’s cold case unit, including Shultz’s and White’s cases.

Furthermore, the cases are not similar enough to point to a serial killer, Campos said.

But over time, solved or unsolved, the city moved on without them.

Today, Payton’s killing ground is part of Atlanta’s Beltline; and the location where Tolbert’s body was found strangled to death is now the site of high-rise condominium in development.

Other mid-1990’s female strangulation homicides still unsolved, according to the APD, include:

- Bernice Bettis, 34, killed May 21, 1996

- Barbara Elias, 31, killed Dec. 30, 1995

- Tanish Williams, 34, killed Feb. 4, 1995

- Laton Farley, 30, killed Feb. 24, 1995

- Barbara Barnhill, 31, killed Jan. 8, 1995

- Valencia Seals, 31, killed July 14, 1995

- Markisha Brown, 16, killed May 31, 1995

- Pamela Walton, 31, killed Sept. 11, 1997

- Anastasia Brazil, 20, killed April 15, 1994

- Denise Glass, 36, killed Dec. 13, 1996

- Emmajean Jenkins, 42, killed July 24, 1994

- Sandra Taylor, 37, killed June 14, 1994

- Patricia Sheffield, 40, killed June 17, 1996

- Jasmine Miller, 27, killed March 12, 1994

Was metro Atlanta a serial killer’s playground? Or multiple?

“Most police administrators on the higher end would rather eat glass, than say we have a serial offender,” Agan said. “Why it was better to say we have 10 murderers out here instead of saying we suspect have one guy who is responsible for 10 murders?”

The media noticed that several drug-addicted prostitutes were turning up dead in the years leading up to the ’96 summer Olympics. But, leaders publicly disagreed.

Atlanta Mayor Bill Campbell denied that there was a serial killer in his city.

“A huge headline indicating serial killer on the loose, that’s irresponsible,” he said in a press conference during the ’90s strangulations.

According to Dr. Michael Arntfield, a retired homicide detective and founder of Canada’s Cold Case Society, an algorithm by the Murder Accountability Project (M.A.P.), the world’s largest database of homicides, indicates just that. Atlanta was likely home to some of the most prolific serial killers, or dozens of single killers at work during that time frame, or a combination of both, he said.

“The stigma of being associated with one or more serial murderers, particularly in this area, the Olympic park area, that would be something that they would want to make go away very quickly,” Arntfield said.

“To have a serial murderer operating in the vicinity of the Olympic Park area, I can’t imagine the political pressure that the police and quite frankly the mayor’s office would have been under at the time,” Arntfield said. “Very few police departments want to admit that the term (serial killer) exists, much less that they have a serial killer in their city.”

“You can imagine in a city like Atlanta, standing on the precipice of international acclaim… in the wake of the ’96 Olympics, Atlanta, sort of comes of age… I can only imagine in ’94, ’95, ’96, the years leading to the ’96 Olympics, the stigma associated with having a serial killer here in Atlanta,” he continued.

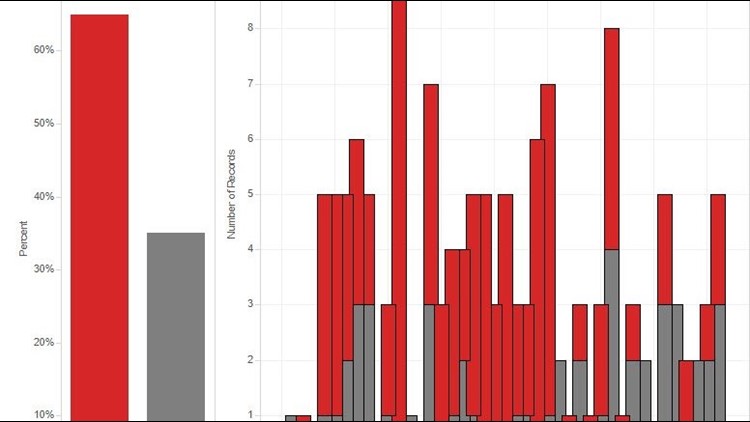

Arntfield said that he sees evidence of six or seven serial killers operating in metro Atlanta. The alternative is more than 40 individual strangles from 1993 through 1998, and more than 100 killers from 1977 through last year.

“When you see one, two, three, 30, a hundred in the same city, you know you have a problem. And until now, until our data revealed this problem, it seemed no one else knew this was the case,” he said. “You need to treat these murders as a series, investigate them as a series, and proceed on that basis until proven otherwise.”

Arntfield, who is on the Murder Accountability Project board of directors and is a professor of criminology at Ontario’s Western University, investigates cold cases.

Numbers, data and an algorithm have done what detectives haven’t been able to do—outline the largest cluster of unsolved strangulation murders of women in the nation—more than 130 women who were strangled or asphyxiated to death, spanning over four decades, as reported to the FBI.

Most of these murders were committed within the city of Atlanta; all within the metro area.

PHOTOS | Murder by numbers

As a retired homicide detective himself, he and his student volunteers, who are part of the Cold Case Society, based in London, Ontario, have worked with some of Atlanta metro’s investigators to confirm links between the killings, and to identify possible serial killers who were previously unknown to police.

The city is now his focus when investigating cold cases.

“Six to seven killers who have eluded identification, some of whom may still be walking the streets of the city tonight,” Arntfield surmised.

Drew has put that life and the streets behind her.

Her son took his own life two years ago and that has made the mother re-evaluate her life.

“I want to honor him for the rest of my life. He never really got to see me 100 percent well,” she said.

She was six-months clean at the time of this interview.

“God has put something in me, I just don't give up. I just don't; it's just not in me. My great-grandmother used to say, ‘Persevere. Persevere.’”

“I'm alive because God saw fit to see me through this, so that I could sit here right now and tell you my story. That's why. Because it needs to be heard. Those young ladies out there deserve to be heard. That's why I'm alive.”

She thinks about her life now and the girls she left behind on the streets, who never made it out.

“These girls never had an opportunity, the ones that did die, never had an opportunity to make it up to their kids. You know, I can look at my kids. I can see my kids,” Drew said.

“I consider myself a survivor. I've been through a lot of bad things, but it does not define who I am today. And I survived. I survived.”

If you have any information that could help solve any of these or other cases, contact the APD at, (404) 614-6544, Dekalb County Police at, (678) 406-7929, Gwinnett County Police at,

(770) 513-5700, or Conyers Police at, (770) 483-6600.

Do you have a tip for the 11Alive investigators about The Hunt? Send Brendan Keefe and Jessica Noll an email at TheHunt@11Alive.com.