When Jasmine Hollie found out she was pregnant, her boyfriend Dominque Garrett, hoped they would have a little girl. He got his wish. Bambi’Tadae Hollie’s is now three-years-old, but Garrett isn’t around to enjoy seeing her grow up.

In September 2016, someone shot and killed the 29-year-old father outside an apartment complex in southwest Atlanta. Authorities believe one of the guns used to shoot Garrett was stolen in 2015 from a home a few miles away.

Dominque Garrett

According to court records, the same gun was used in a different shooting before Garrett’s death. A detective investigating Garrett’s case wrote in a report “I received a phone call from Inv. Kilgore and he advised me that the shell casings on my homicide scene and the aggravated assault scene (Inv. Hogan’s case) match the 762x39 gun found on my homicide scene….”

Hollie believes her boyfriend’s death could have been prevented. “All of it could have been avoided if that gun wasn’t on the street," said Hollie.

Garrett’s death highlights a growing problem in Atlanta and across the country. According to records obtained by the 11Alive Investigators, stolen guns in Atlanta were involved in at least 455 crimes over the past seven years. That’s more than 60 homicides, robberies, assaults and other violent crimes.

It's a national problem.

American gun owners, preoccupied with self-defense, are inadvertently arming the very criminals they fear.

Hundreds of thousands of firearms stolen from the homes and vehicles of legal owners are flowing each year into underground markets, and the numbers are rising. Those weapons often end up in the hands of people prohibited from possessing guns. Many are later used to injure and kill.

A yearlong investigation by The Trace and more than a dozen NBC TV stations identified more than 23,000 stolen firearms recovered by police between 2010 and 2016 — the vast majority connected with crimes. That tally, based on an analysis of police records from hundreds of jurisdictions, includes more than 1,500 carjackings and kidnappings, armed robberies at stores and banks, sexual assaults and murders, and other violent acts committed in cities from coast to coast.

“The impact of gun theft is quite clear,” said Frank Occhipinti, deputy chief of the firearms operations division for the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives. “It is devastating our communities.”

Thefts from gun stores have commanded much of the media and legislative attention in recent years, spurred by stories about burglars ramming cars through storefronts and carting away duffel bags full of rifles and handguns. But the great majority of guns stolen each year in the United States are taken from everyday owners.

Thieves stole guns from people’s closets and off their coffee tables, police records show. They crawled into unlocked cars and lifted them off seats and out of center consoles. They snatched some right out of the hands of their owners.

In Pensacola, Florida, a group of teenagers breaking into unlocked cars at an apartment complex stole a .22-caliber Ruger handgun from the glovebox of a Ford Fusion, then played a videogame to determine who got to keep it. One month later, the winner, an 18-year-old man with an outstanding warrant for his arrest, fatally shot a 75-year-old woman in the back of the head who had paid him to do odd jobs around her house. She had accused the gunman of stealing her credit cards.

In Gilbert, Arizona, a couple left four shotguns out in their bedroom and two handguns stuffed in their dresser drawers even though they had a large gun safe in the garage. They returned home to find their sliding backdoor pried open and all six of the weapons missing. Police recovered one of the shotguns eight months later on the floor of a getaway car occupied by three robbers who held up a gas station and led officers on a harrowing chase in the nearby city of Chandler.

In Atlanta, a thief broke through a front window of a house and stole an AK-47-style rifle from underneath a mattress. The following year, a convicted felon used the weapon to unleash a hail of bullets on a car as it was leaving a Chevron gas station, sending two men to the hospital. Two months later, the felon used the rifle to fatally shoot his girlfriend’s 29-year-old neighbor. A 7-year-old girl who witnessed the killing told police the crack of the gunfire hurt her ears. She ran home crying to her mother.

After the Las Vegas and Sutherland Springs mass shootings, attention fell on exotic gun accessories and gaps in record keeping. Last week, a new measure intended to shore up the federal background check system was introduced by eight U.S. senators. But many criminals are armed with perfectly lethal weapons funneled into an underground market where background checks would never apply.

In most cases reviewed in detail by the Trace and NBC, the person caught with the weapon was a felon, a juvenile, or was otherwise prohibited under federal or state laws from possessing firearms.

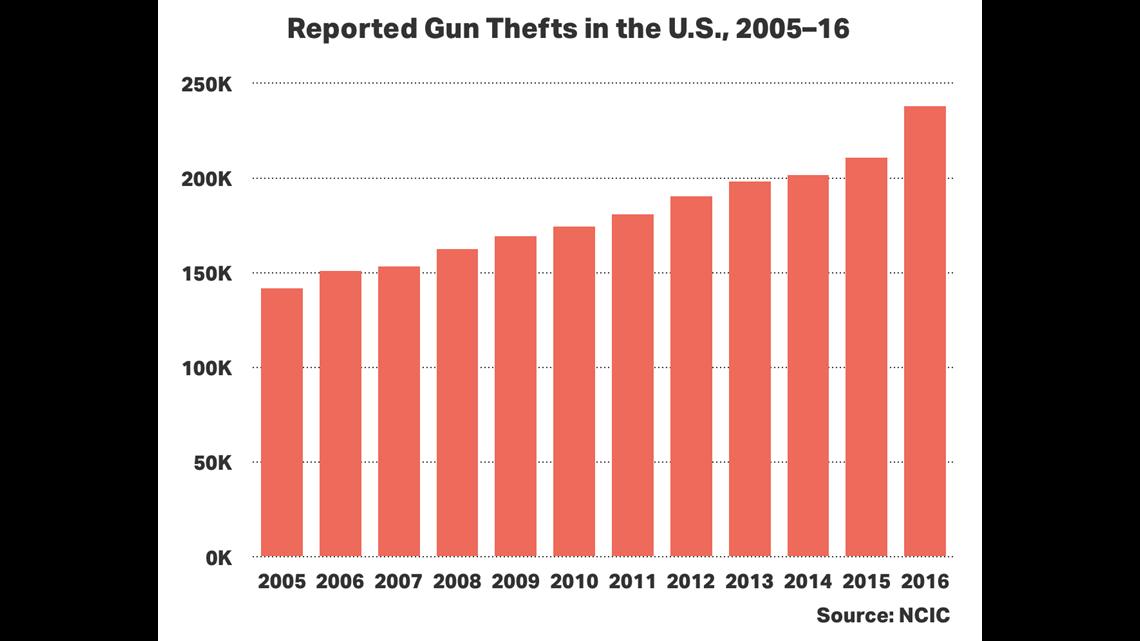

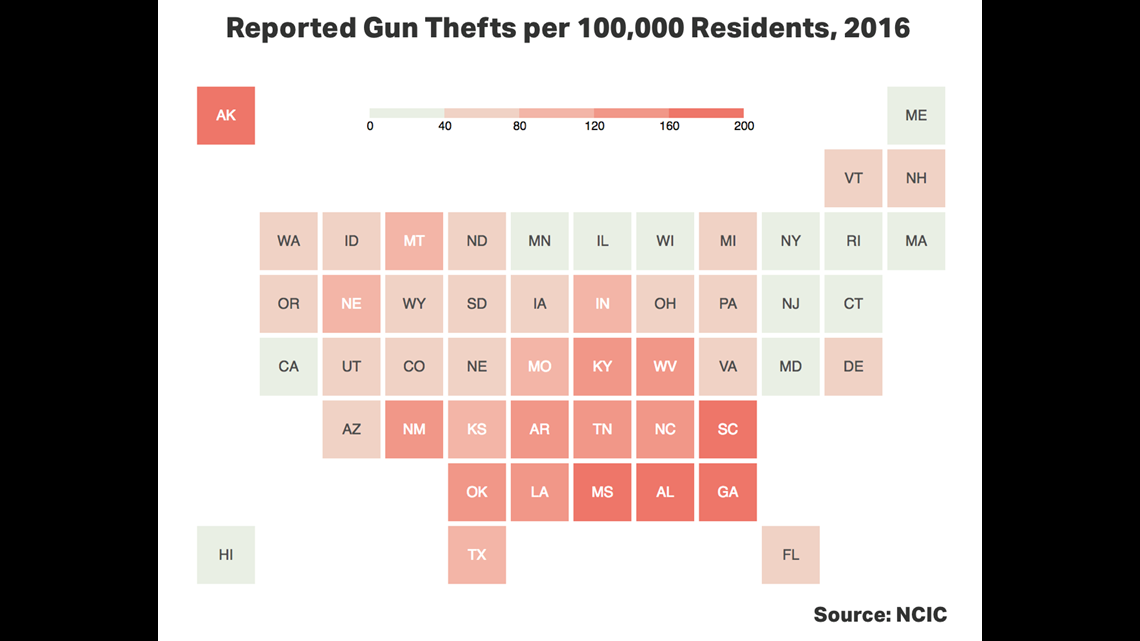

More than 237,000 guns were reported stolen in the United States in 2016, according to previously unreported numbers supplied by the National Crime Information Center, a database maintained by the Federal Bureau of Investigation that helps law enforcement track stolen property. That represents a 68 percent increase from 2005. (When asked if the increase could be partially attributed to a growing number of law enforcement agencies reporting stolen guns, an NCIC spokesperson said only that “participation varies.”).

All told, NCIC records show that nearly two million weapons have been reported stolen over the last decade.

The government’s tally, however, likely represents a significant undercount. A report by the Center for American Progress, a left-leaning public policy group, found that a significant percentage of gun thefts are never reported to police. In addition, many gun owners who report thefts do not know the serial numbers on their firearms, data required to input weapons into the NCIC. Studies based on surveys of gun owners estimate that the actual number of firearms stolen each year surpasses 350,000, or more than 3.5 million over a 10-year period.

“There are more guns stolen every year than there are violent crimes committed with firearms,” said Larry Keane, senior vice president of the National Shooting Sports Foundation, the trade group that represents firearms manufacturers. “Gun owners should be aware of the issue.”

On a local level, gun theft is a public safety threat that police chiefs and sheriffs are struggling to contain. The Trace requested statistics on stolen weapons from the nation’s largest police departments in an effort to understand ground-level trends. Of the 80 police departments that provided at least five years of data, 61 percent recorded per-capita increases in 2015 compared to 2010.

The rate of gun thefts more than doubled in Sioux Falls, South Dakota; Madison, Wisconsin; and Pasadena, California, our analysis found.

More than two-thirds of cities experienced growth in the raw number of stolen-gun reports, not accounting for population change.

There were 843 firearms reported stolen in St. Louis in 2015 — a 27 percent increase in reports over 2010.

“We have a society that has become so gun-centric that the guns people buy for themselves get stolen, go into circulation, and make them less safe,” said Sam Dotson, a former St. Louis police chief.

As The Trace has previously reported, gun thieves in many cities have learned to target cars and trucks, finding them a reliable supply of unsecured firearms. The per-capita increase in gun thefts from vehicles increased 62 percent, in cities that provided complete data.

Thefts are surging as gun sales have hit record highs in recent years, a trend driven by owners who surveys show are increasingly buying weapons for the purpose of self-defense, and who have been given legal authority to take their weapons into more and more public places.

In some instances, thieves stole firearms even after gun owners took precautions, like locking their weapons in a safe. But in most cases reviewed by The Trace and its partners, guns were taken from people who left their weapons in unlocked homes and cars, and in other places where they were easy to grab.

A woman in St. Louis told police she drove around with three guns in a plastic bag because she was worried about crime in her neighborhood. One morning in 2011, she found that a thief had ransacked her car and had run off with the weapons. She couldn’t remember if she had locked her doors. One of the guns, a Hi-Point pistol, surfaced the following year at a murder scene. A good Samaritan stopped his car on the northern end of the city to help two men who said they were out of gas. The men robbed him and then shot him in the chest.

“It comes down to basic human responsibility,” Occhipinti, the ATF official, said. “If a gun owner doesn’t do what he’s supposed to be doing, that obviously makes our job a lot harder.”

Identifying the precise nexus between stolen firearms and other forms of crime is a question that has flummoxed researchers and journalists for years, in part because of strict legal limits on the public’s access to national data. The ATF is barred under a rider to a Department of Justice appropriations bill from sharing detailed crime gun data, which could include information about whether a weapon was stolen, with anyone outside of law enforcement.

The Trace and NBC sidestepped federal restrictions, in part, by obtaining more than 800,000 records of both stolen and recovered firearms directly from more than 1,000 local and state law enforcement agencies in 36 states. Matching the serial numbers of guns contained in the two sets of records enabled our reporters to identify crimes involving a weapon that had been reported stolen.

The trend is unambiguous: Gun theft is on the rise in many American cities, and many of those stolen weapons are later used to hurt and kill people.

More guns carried in public, more opportunities for thieves

In 1995, Jerry Patterson, a state senator representing the Houston area, authored a bill to give Texans the right to carry concealed weapons in public.

Patterson, a self described “gun guy,” said his constituents were clamoring for the ability to protect themselves. It was the mid-’90s, and crime was on the rise. Just four years earlier, Texas experienced what was then the worst mass shooting in its history, when a gunman drove his truck through the front window of a Luby’s restaurant in the town of Killeen, then shot and killed 23 people.

Patterson’s bill was aided by testimony from Suzanna Hupp, one of the survivors of the massacre. “She stood up and simulated, with her thumb and forefinger, a totally in-control shooter by pointing at various members of the Senate,” Patterson recalled. “It got your attention.”

Since that bill became law, Texas has legalized carrying handguns openly in public, enacted a law allowing guns on college campuses, and made it possible for residents to legally carry firearms in cars without permits.

“You can unequivocally and clearly say there are no safe spaces anywhere,” Patterson said. “And the least-safe space is the place known as a gun-free zone.”

A 2015 survey by researchers at Harvard and Northeastern universities describes a fearful American gun owner increasingly concerned about his or her safety even as the national crime rate has fallen sharply over the past 25 years. Two out of three gun owners said that self-defense is a primary motivation for owning a firearm.

Those same gun owners acquired roughly 70 million firearms in the past two decades, swelling the civilian gun stock to an estimated 265 million weapons. The buying binge has been propelled by a series of high-profile mass shootings and a concerted push by the gun lobby to encourage gun carrying in public as a defense against dangers real and perceived.

A research paper published this year, using responses from the Harvard and Northeastern survey, estimated that three million Americans carry loaded handguns in public every day. About nine million people carried a handgun at some point during the month before the survey was conducted, researchers found. Six percent of respondents who said they carried a gun had been threatened with a firearm in the previous five years.

It is easier for these gun owners to legally carry in more public places in more states than ever before. In the past two decades, dozens of states have passed legislation easing restrictions against carrying in public. Some, like Georgia, have made it possible to legally carry a concealed weapon in restaurants and churches. At least 12 others, including Missouri, Arizona, and West Virginia, have done away with all training or licensing requirements, meaning anyone legally allowed to own a gun can carry it concealed in public.

Researchers have found that the same behaviors sharply increase the odds that a gun will slip into the hands of a thief. People who owned guns for protection or carried a gun in the previous month were more than three times as likely to have experienced a theft in the previous five years, according to a study published this year that was based on the Harvard and Northeastern survey results. People who owned six or more guns and stored their guns loaded or unlocked — or kept guns in their vehicles — were more than twice as likely to have had their firearms stolen.

In Texas, gun owners have reported thousands of thefts. Austin alone tallied more than 4,600 reports of lost or stolen guns between 2010 and 2015, more than 1,600 of which were swiped from cars, The Trace and NBC found. Over that same period in Austin, lost and stolen guns were recovered in connection to at least 600 criminal offenses, including more than 60 robberies, assaults, and murders.

Many gun-rights advocates, including Patterson, believe that owners have a responsibility to guard their weapons from theft.

“You’re negligent if you don’t exercise good judgment,” he said. “There’s too many guns in the hands of dumbasses that don’t know how to use it, don’t know how to store it.”

In Houston about a decade ago, someone broke into Patterson’s truck, making off with a Smith & Wesson .357 revolver. “Now I don’t leave handguns in the car,” he said.

Instead, Patterson now keeps a shotgun under the back seat.

“It’s harder to steal a long gun discreetly,” he said.

Gun theft from vehicles has become especially problematic outside stadiums and other public spaces where firearms are banned. Thieves have so avidly prowled for guns left by fans in unlocked cars in the parking lot of Busch Stadium in St. Louis that a local entrepreneur proposed charging Cardinals fans a fee to lock their guns in a giant truck outside the ballpark. The city rebuffed the idea, urging gun owners to leave their weapons at home.

Law enforcement officials have sought to combat the theft of firearms from vehicles by posting online videos about safe gun storage. One Texas police department bought billboard ads alongside the highway. But several officials said in interviews that their efforts are being stymied by a general carelessness among gun owners.

The International Association of Chiefs of Police recently tasked a team of top of law enforcement officials to develop a program that police officers and sheriff’s deputies can use to press gun owners into safeguarding their weapons. At the organization’s annual conference in Philadelphia in October, the team premiered a public service announcement that showed a burglar stealing a gun from an unlocked car and then embarking on a robbery spree.

“We leave our cell phones in our cars, and we go crazy. But you leave your firearm and it’s like we forget,” said Armando Guzman, a chief of police from Florida who was one of the principal architects of the prevention effort. “Look at the consequences.”

In Akron, Ohio, a woman left a purse containing a .380-caliber Kimber pistol inside her unlocked Jeep Cherokee. When she returned, the purse was lying across the street with everything still inside — except the pistol. Three days later, a group of teenagers were playing with the gun when it went off, killing a 17-year-old boy.

Most states don’t require gun owners who leave weapons in a car or truck to secure them against theft. Kentucky’s law specifically says that owners may keep firearms in a glove compartment, center console, seat pocket, or any other storage space or compartment regardless of whether it is “locked, unlocked, or does not have a locking mechanism.”

Cities in states that rolled back restrictions on carrying weapons in public or storing them in cars over the last decade often saw sharp jumps in firearms being stolen from vehicles in the years afterward.

In 2014, Governor Sam Brownback of Kansas signed into law a blanket prohibition on municipalities regulating the transportation of firearms. The following year, he approved a bill eliminating licensing requirements for carrying concealed guns. By the end of 2015, the number of guns stolen from cars in Wichita topped 200 for the first time in at least a decade, police reports show.

The analysis by The Trace and NBC shows that stolen firearms were involved in at least 570 criminal offenses in Wichita between 2010 and 2016. That count includes nearly 60 assaults and robberies and at least nine killings. A hundred cases involved individuals suspected of dealing or possessing drugs, and 77 involved felons in possession of firearms.

Homes are generally a more secure place to store firearms, but even indoors, guns can be a magnet for thieves.

Researchers at Duke University and The Brookings Institution found in 2002 that thieves were more likely to break into homes in areas where gun ownership rates were high. The researchers concluded that instead of being a deterrent to crime, guns enticed thieves looking for a lucrative score.

In a large share of the burglaries in which a gun was stolen, it appeared that was the only item taken, suggesting that the thief knew the house had a gun in it and went after it, said Philip Cook, a professor at Duke who co-authored the study.

“That’s why people who put up signs that say, ‘This house is protected by Smith & Wesson,’ are taking a chance, just like people who put NRA stickers on their cars are taking a chance,” Cook said. “It signals that this might be worth breaking into.”

In 2012, Justin Johnson took a job working as a doorman at a 24-hour diner in Charlotte, North Carolina. Many nights, drunken brawls broke out in the parking lot, so he bought a 9mm Ruger SR9c pistol.

“People just go crazy for no reason,” Johnson said. “You don’t feel safe.”

In 2015, Johnson left home to pick up his son from football practice. He tucked the pistol behind a photograph on his living room bookshelf, and locked the doors to his house. While he was gone, a thief sneaked in through an open window, snatched his gun and ran off.

Two months later, Charlotte police found the Ruger in the possession of a convicted felon. According to a police report, he had assaulted two police officers.

Johnson didn’t know that his firearm had been recovered until a reporter for The Trace called him this month. He was alarmed that his gun was in the hands of a criminal. “That’s the last thing I ever wanted,” he said. “I got it to use against somebody like that.”

Stolen guns sell fast, but danger is lasting

Guns are easy for thieves to find — and easy to sell. P. Kentris, a gang member in Colorado who asked that his full first name not be published, pleaded guilty to burglary in 2012 after he and a group of friends broke into a house. They made off with a guitar, jewelry, video games, and five guns.

Unloading his haul was straightforward. “I just told people I had guns for sale,” he said. Kentris said he sold four of the weapons — three handguns and one rifle — for about $1,400 before he was arrested.

Of the nearly 150,000 records of stolen weapons analyzed by The Trace and NBC in which the type of gun was listed, 77 percent were handguns.

Law enforcement officials and researchers say that stolen guns are usually sold or traded for drugs. “Guns are the hottest commodity out there, except for maybe cold, hard cash,” said Kevin O’Keefe, the chief of the ATF’s intelligence division. “This is a serious issue.”

Most stolen guns were recovered within the same city or state as the scene of the theft, sometimes years or even decades later, The Trace and NBC found.

In 2007, a burglar smashed a window on the back door of a home in Leon County, Florida, and made off with a .25-caliber Taurus pistol. Eight years later, Emmett Reid, then 21, met a man outside an apartment complex in the same county to sell him two ounces of marijuana. After the man got into the passenger seat of Reid’s car, he shot and wounded Reid in the stomach with the stolen gun.

The Trace and NBC identified more than 500 guns that were stolen and then crossed state lines, sometimes traveling hundreds or even thousands of miles, before turning up at the scene of a crime. Many of those guns followed trafficking routes that are well known to law enforcement, flowing from states with looser laws to states with stricter ones.

A Smith & Wesson stolen from an unlocked pickup truck in Florida was recovered in connection to a shooting in Camden, New Jersey. A revolver stolen in Hampstead, New Hampshire, found its way to Boston, where police stopped a gunman at a high school graduation. A .380-caliber Jimenez pistol stolen from a house in Hammond, Indiana, came into the possession of an 18-year-old gang member in Chicago, who tossed it onto a front porch while he was running from police.

In South Carolina, a former state trooper reported his .40-caliber Glock stolen from his unlocked pickup in 2008. The gun was recovered during a drug arrest and the former trooper got it back, only to have it stolen from his truck again in 2011. Four years later, New York Police Officer Randolph Holder, 33, was responding to reports of a shooting in East Harlem when he encountered Tyrone Howard, a 30-year-old felon who had been in and out jail since he was at least 13. Howard pulled out the stolen Glock pistol and fatally shot Holder in the head.

Few states require gun owners to report theft.

When a gun store is burglarized, it must report any missing firearms. Under federal law, licensed firearms dealers have to maintain records — including the make, model, and serial number of each gun in their inventory — and provide them to investigators so they can attempt to recover the weapons.

Everyday gun owners are not held to the same recordkeeping requirements. Only 11 states and the District of Columbia have a version of a law that requires gun owners to report the loss or theft of a firearm to police. Law enforcement officials say stolen-gun reports help them spot trends, deploy resources, and get illegal weapons off the street.

Keane, the National Shooting Sports Foundation’s senior vice president, said that while gun owners should lock up their weapons when they’re not in use, he opposes penalizing gun owners who don’t report a theft. “The focus has to be on criminals,” he said. “If they’re using stolen firearms then there should be severe consequences from that.”

But law enforcement experts and advocates of gun-violence prevention say that the attention should be on preventing thefts from happening in the first place. Massachusetts is the only state where gun owners must always store firearms under lock and key, according to the Giffords Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence. California, Connecticut, and New York require guns to be locked in a safe or with a locking device in certain situations, including when the owner lives with a convicted felon or domestic abuser.

All four states experience theft rates well below the national average, according to NCIC data.

“There ought to be some obligation in the law for gun owners to responsibly secure their firearms,” said Senator Richard Blumenthal, a Connecticut Democrat. “Congress should not only be looking at this issue, they ought to be acting on this issue.”

In Colorado, surging thefts, and a stalled gun-storage law.

In 2012, a gunman walked into a Century movie theater in Aurora, Colorado, and fatally shot 12 moviegoers and wounded another 70. Advocates for gun-violence prevention and the Democrat-controlled state Legislature moved swiftly to introduce legislation to expand background checks to private sales and cap the ammunition capacity of magazines at 15 rounds.

The lawmakers who authored the bills received a flood of angry emails and death threats. “It was pretty intimidating,” said Beth McCann, then a Democratic state representative who helped shepherd the legislative package.

The bills were ultimately adopted, but Colorado still allows gun owners to travel with weapons in their vehicles without a permit, basically under any circumstance. The state does not require owners to report guns when they go missing. And it is one of more than 40 states with a preemption law that prevents local municipalities from adopting their own gun restrictions.

Colorado also does not have a safe-storage law. Gun-violence prevention groups wanted the post-Aurora package to include a provision requiring that owners lock up their weapons when not in use, but the idea fizzled. Lawmakers behind the bills feared losing support from their colleagues whose more rural constituencies wanted to be able to access their guns quickly during an emergency.

“The legislation had to be rural friendly and urban friendly, but finding the right balance was difficult to strike,” said Rhonda Fields, a Democratic state senator from Aurora who spearheaded the legislative drive. “Locking up guns was on there, it’s just that we took the lower-hanging fruit.”

In the three years after the movie theater shooting, at least 2,150 guns were reported stolen to police in Aurora and nearby Denver, according to police records. Stolen firearms were involved in nearly 200 crimes in the two cities between 2013 and 2015, The Trace and NBC found, including an ambush-style attack on police officers and the murder of a 34-year-old construction worker.

Some of the purloined guns were practically handed to criminals. In 2015, Ricky Lee Denny’s .380-caliber Kel-Tec pistol was stolen, along with his Jeep Grand Cherokee, when he left the vehicle running in front of his Denver home to retrieve a cake for a family Thanksgiving dinner. A few days later, Phillip Munoz, a fugitive wanted for assault and kidnapping, was killed by police after he led officers on a chase and then threatened them with Denny’s stolen weapon.

“It was a hard lesson: Don’t leave it in there,” Denny said. “Take your guns inside when you park your car.”

Other firearms were taken from places that were more secure — but still vulnerable to theft.

In June 2013, Brandon Moore’s family moved into a new home in Douglas County, about a 30-minute drive outside Denver. That day, his wife stashed his .40-caliber Smith & Wesson pistol behind her husband’s cowboy hat on the top shelf of a closet.

When Moore went to look for his pistol later, it was gone, along with a loaded 13-round magazine. Moore suspected the movers. Sheriff’s deputies investigated, but the case went nowhere, Moore said.

Two years went by with no sign of Moore’s gun. Then, late on September 16, 2015, it resurfaced in a shooting that left two families devastated

A stolen gun takes a father's life and a teen athlete's legs

Bobby Brown, 34, lived with his wife and four children in a brick apartment complex in the Montbello section of Denver. Brown worked in construction and moving jobs, but his true passion was music. On that late summer night, he fell into an argument with a drunken neighbor.

Brown headed down to fetch cigarettes from his baby-blue Cadillac. His oldest daughter, Shanice, then 13, was in bed, unable to sleep because of the quarrelling. Worried about getting up for school the next day, she went to tell her father to keep it down.

As Shanice stepped outside, gunfire erupted from the parking lot. Brown turned to run away, but bullets struck his back and neck. Shanice watched as her father crumpled to the pavement.

Across a courtyard, Aysia Quinn, a 17-year-old high school basketball player, saw bullets sparking across the pavement. She turned to run back up the stairs, but only a little way up, her legs gave out. She had been struck by two errant rounds. One hit her underneath her arm; the other lodged in her lower spine.

Brown was pronounced dead at the hospital that night. Quinn was rushed into surgery and woke up the next day strapped to the bed; she had tried to pull the tubes out of her throat in her sleep. She went to stand up, but still couldn’t feel her legs. She was paralyzed from the waist down.

“I didn’t deserve this,” she said in an interview. “It ruined what I wanted to do.”

The gunman was Jesse Oliver, then 32, a suspected gang member whose criminal history included crimes like weapons possession and child prostitution. He could not have passed a background check to acquire a gun legally.

On the night of the shooting, an officer who happened to be nearby heard the shots. He spotted Oliver running and stopped him. Oliver had already tossed the Smith & Wesson that had been stolen from Brandon Moore two years earlier, but two eyewitnesses later picked him out of a photo lineup as the shooter.

A month later, a man helping his parents clean their backyard found the gun lying on a pile of firewood. Ballistics confirmed it was the firearm used in the homicide and assault. Oliver was sentenced to life in prison.

Prosecutors believe Bobby Brown was the intended target but never determined a motive. Witnesses told police that Oliver might have been looking for rival gang members to shoot, but there was no evidence indicating that Brown belonged to a gang.

“Our understanding was that Bobby was walking away, he wasn’t armed, he didn’t appear to be a threat,” said Phil Reinert, a deputy district attorney who prosecuted Oliver. “By all accounts, he was a good man, caused no problems. He was just trying to watch out for his kids.”

Quinn said she struggled with pain and rehabilitation after the shooting. At one point, she begged in vain for doctors to amputate her legs.

Quinn is 19 now, and her outlook is brighter. She’s recovered enough feeling in one of her legs to lift it off the ground. But some days are still tough. She’s nervous about being around large groups of people and shudders at any loud popping sounds. She cries and prays over her legs and hopes she can play basketball again.

“My goal is by 21 to be walking again,” she said. “I don’t want to settle for less.”

Brown’s family has also struggled. On Sundays, he and his aunt Renay Brown used to like to sit and sip Miller High Life beer while arguing over football. Renay was a Dallas Cowboys fan; Bobby loved the Denver Broncos. Renay still says good morning to a framed photograph of her nephew on the bookshelf by her front door. She still watches football with her Miller High Life. She wishes Bobby could be there, even if he did bash her Cowboys.

The family, she said, has hasn’t found a way to explain Bobby’s death to his youngest child. The girl can’t seem to grasp why the closest she can get to her father is the box holding his ashes. “She tells us to go get him out that box,” Renay said, her cheeks stained with tears. “What do you tell her?”

Renay didn’t know that the gun used to kill her nephew was stolen until she was told by a reporter. At first she seemed surprised, but then said it is easy to find a gun on the street. “It’s like you and me getting up and going down to the nearest 7-Eleven to get a Slurpee,” she said.

Moore, who legally purchased the murder weapon, was one of several gun owners contacted by The Trace who didn’t know that his stolen firearm had been used in a crime. “Are you serious?” he said, when told it was used to shoot two people. “That’s exactly why I reported it stolen, because I was afraid something like that was going to happen.”

He then asked how he could get the gun back.

Max Siegelbaum, Miles Kohrman, and Mike Spies of The Trace; Katie Wilcox and Chris Vanderveen of 9News in Denver; and journalists from several other NBC TV stations contributed reporting. Read about the full partnership here.