'There are no criminals there': Community activists push for Atlanta to close the city jail

This investigation looks at all sides of the argument to close or keep the city detention center. After years of the debate, where are we now?

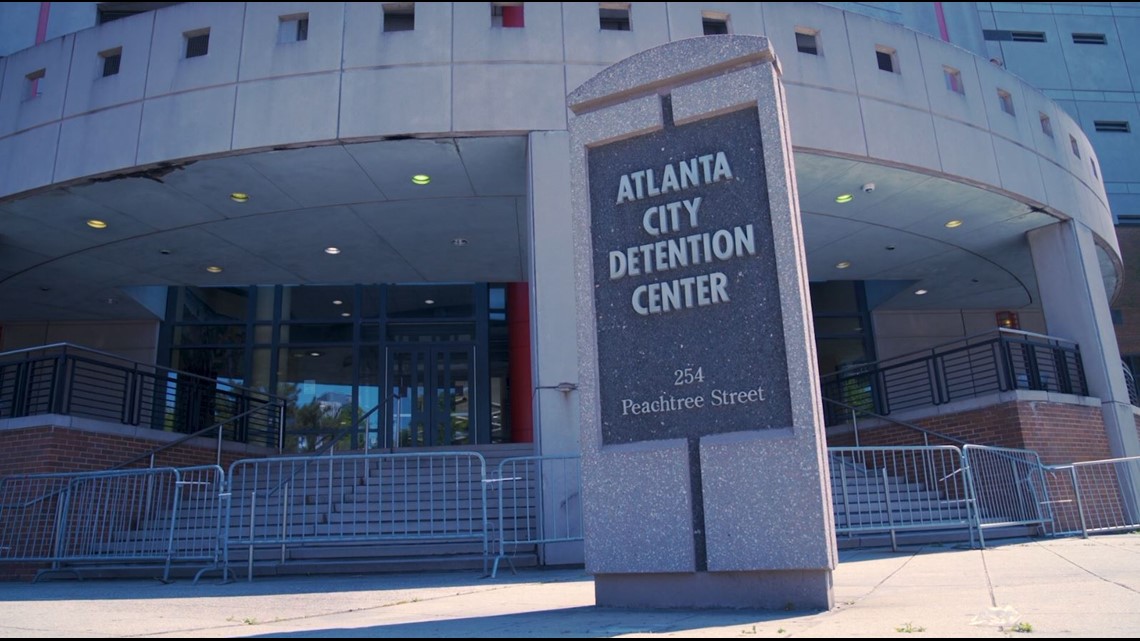

An Atlanta building, barely a quarter-century old, stands tall on the city's south side. But it's the history and the community's battle over the building that casts an even bigger shadow.

Built in the '90s as Atlanta won the bid to host the Olympics, the Atlanta City Detention Center made national headlines.

It was made to house low-risk individuals who violate city ordinances and commit low-level offenses. Around the same time, the city passed an ordinance that made loitering a new punishable offense.

The community pushed back saying it was a way to penalize the homeless population and rid the city streets of them.

Since the '90s the debate has only grown over the use of the jail, with many voices on the side of closing the jail as well as many saying the jail needs to remain open, but "reimagined".

The conversation around criminal reform has noticeably changed since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic and the spike in crime in Atlanta.

Here's what the community, advocates on both sides, and Atlanta Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms had to say about whether the jail should or should not close.

► WATCH | Extended interview with Mayor Bottoms at bottom of story

ATLANTA SPEAKS

The screen is mostly white, except for the giant-sized logo of the city of Atlanta. Over the logo are two words, written in thick blue letters: PUBLIC COMMENT.

“It is unreasonable to think that anyone would close our city jail.”

“The city jail, I’m not sure what it’s being used for.”

“I hope you guys open the city jail for a few reasons. Public safety is completely out of control …”

“We certainly need to have more jail space so that these offenders can be put in jail and know they’re going to stay there for a while.”

For 40 minutes, dozens of people – presumably Atlanta residents – share their thoughts during an early March meeting of the Atlanta city council’s public safety committee. Meetings like these don’t often draw such attention, but these meetings – with this committee – have done so all year.

The subject at hand? The city jail.

“The Atlanta detention center should not be repurposed.”

“Crime has gotten way out of hand all over Atlanta.”

“We have to do everything we can right now to make our city safer.”

Most, though not all, of the callers express a similar line of thought. Crime in the city of Atlanta, they say, is out of control. Since the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, crimes of all nature – but particularly violent crimes and homicides – have spiked to levels not seen in years. The solution, say the callers, is to put those responsible in the Atlanta City Detention Center.

The detention center – one of few city jails in all of Georgia – isn’t used for this purpose. It was built to house those charged with low-level offenses, not the violent crimes and felonies that send people to county jails.

What is the subject of hot debate – and hours of public comment – is a disappointment to those who hoped, by now, it would no longer exist.

BY THE NUMBERS

On the day of ACDC’s unveiling, protesters gathered and chanted, “You close up the park / And open up the jail. / You sweep up the poor / That can’t pay their bail!”

That perception has never changed. And the data shows why.

In 2017, the Atlanta City Detention Center - called ACDC by some - held more than 30,000 Atlantans in custody. Nearly 3,000 were detainees of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), with whom the city entered an agreement seven years earlier. Others were held on city fines or through the U.S. Marshals Service. But the majority – more than 22,000 inmates – were pretrial detainees, held on low-level offenses for which they could not pay bail.

The most common charges?

- Driving with a suspended or revoked license (3,353 inmates)

- Possession of an ounce or less of marijuana (2,002)

- Driving without a tag (1,725)

Many more spent nights in jail for speeding (790), drinking in public (1,069), and failure to obey a traffic control device (1,479). Often these stays were brief, a night or two at most. But others were longer. City records show that Black men arrested for defecating or urinating in public (344) stayed at ACDC for an average of 12 days.

“That’s the message a lot of people don’t know,” said Marilynn Winn, the founder of Women on the Rise. “People think, ‘Oh, where are the criminals going?’ There are no criminals there.”

HISTORY OF ACDC

“You could be riding down the street with a broken tail light,” Winn said, “but you’ll get a ticket because you’re able to pay. But for the people that are not able to pay, they are locked up in that jail.”

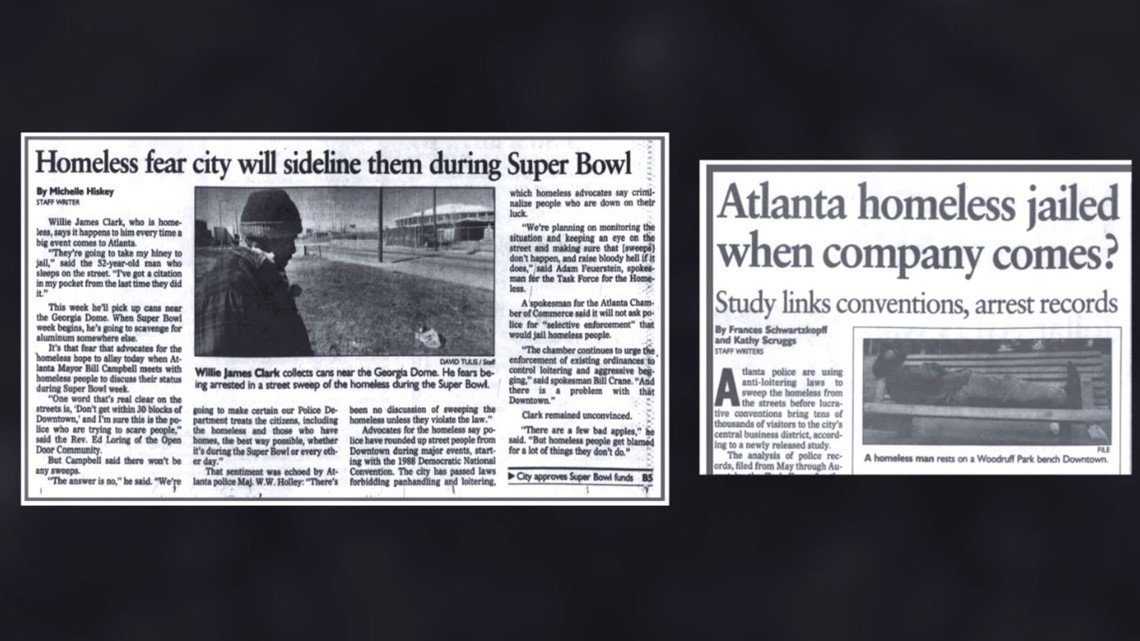

And since ACDC’s first days of existence, advocates for homeless and poorer Atlantans claimed it only existed to put them out of sight.

“The detention center rises out of, what I call in my research, the Olympic-i-fication of Atlanta,” said Dr. Maurice Hobson, an author, and professor at Georgia State. “In 1990, when Atlanta wins the big for the Olympic Games, Atlanta is the most violent city in the United States.”

Indeed, many headlines from the years prior to the Olympics used the FBI’s national crime data to make that claim.

“I was a young African-American male,” recalls Michael Julian Bond, now a city council member representing Post 1 At-Large. “The trend at the time in the country was that African-American males were the number-one murder victims in all the major cities in the country, including Atlanta. It was probably the most dangerous time in Atlanta I’d ever experienced.”

That meant, among other things, an overcrowded jail. A detention center built for 521 inmates averaged nearly double that amount by 1992, according to the city’s then-corrections director Tom Pocock. Again, many of the inmates were low-risk offenders, arrested on charges like public drunkenness. “The floors of cellblock common areas are lined with mattresses for the hundreds of prisoners without beds,” wrote Douglas A. Blackmon in an article for the Atlanta Constitution.

By this point, a new city jail – ACDC – had been approved but not yet built, and the incoming Olympics represented a pivotal time in Atlanta’s history.

“It was an opportunity for Atlanta to present herself to the world,” said Dr. Hobson. “Atlanta [was] really franchising itself for world consumption. So this is part of a facelift to not only incarcerate those that have committed crimes … but also the homeless.”

This was not unusual to the Olympics, Councilmember Bond points out.

“Having worked in the old jail,” he said, “that was a running joke, that if there was a big convention in town, the streets would be swept, and the homeless would be incarcerated. And there’s some truth to that.”

Around the same time, city leaders introduced ordinances that restricted panhandling, loitering, and other activities that would put many behind bars. In an 11Alive story from the mid-1990s, then-Mayor Bill Campbell defended a controversial loitering ordinance by saying, “There is no reason for people to be loitering in parking lots if they don’t park their car there.”

The city also approved Woodruff Park, then a well-known haven for the homeless, for a $5 million overhaul before the Olympics. Many advocates viewed that as a not-so-subtle way to clear homeless Atlantans from downtown.

The new jail became the center of the debate.

THE IMPACT OF MASS INCARCERATION

It’s a modern building without some of the exterior wear and tear often associated with jails. Yet the building is removed, two MARTA stops away from Mercedes Benz Stadium, State Farm Arena, and the numerous office and high-rise structures that scrape the downtown skies. Most Atlantans, and most visitors to Atlanta, will never pass it.

In many ways, it’s a metaphor for the space that jails occupy in the public consciousness: people are aware they exist but rarely give them even a passing thought.

That’s beginning to change. Advocates for criminal justice reform have become more vocal and organized. Documentaries, such as Ava DuVernay’s The 13th, have reached millions. They’ve all brought to light many of the complexities and harsh truths about racial inequities and the role of mass incarceration in America.

“Incarceration’s Front Door,” a report by Vera Institute of Justice, found that Black Americans are jailed at almost four times the rate of white Americans. Researchers found that 62% of those in jail were not convicted, meaning they had been arrested and were awaiting trial but only stayed behind bars because they could not afford bail.

“I actually feel for those people,” Winn said, as she listened to the public comment of the Atlanta City Council meeting. “They do not know what public safety is. Public safety is not putting a person in jail and letting them back on the streets with nothing.”

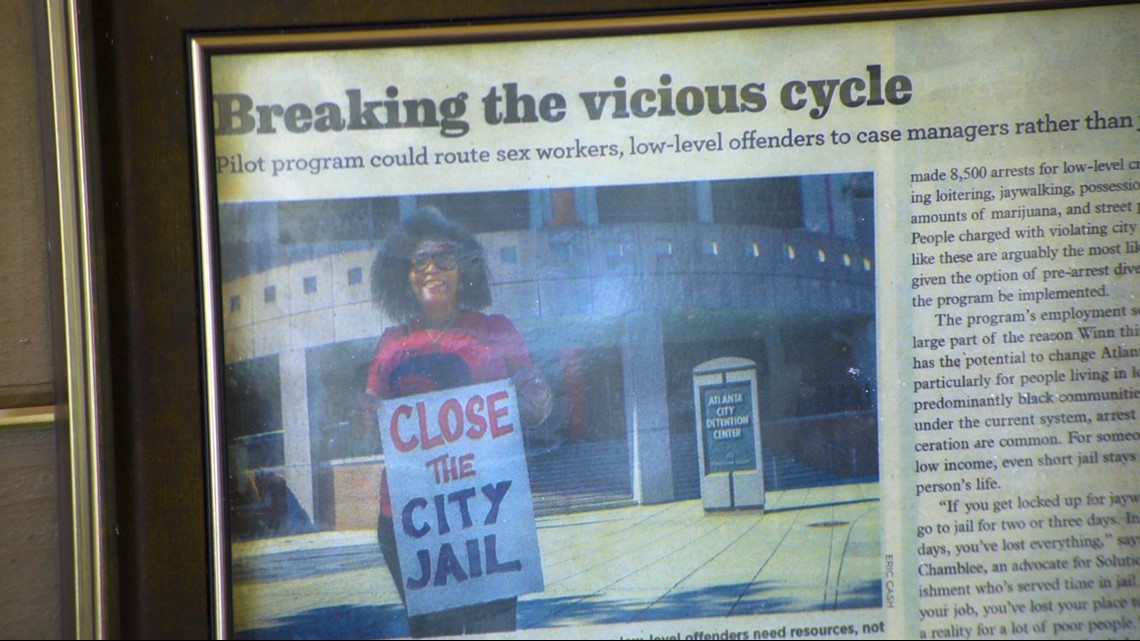

The founder of Women on the Rise says the group is dedicated to empowering and advocating for formerly incarcerated women of color. Winn has been among the loudest voices to close the detention center. It’s a fight she’s waged for more than half a decade – a fight that seemed, for a while, like she was close to actually winning.

“Nobody’s talking about a solution other than putting people back in jail,” Winn said, pausing the video. “So we’ve got work to do to turn that around.”

When it comes to the cost of mass incarceration, Winn sees herself as an example. She was born and raised in Atlanta’s Buttermilk Bottom – “maybe the first hood or first ghetto,” she calls the area that’s now the Old Fourth Ward. She says a family member taught her how to shoplift. She recalls being arrested at the age of 17, going to court at 18, and receiving a two-year prison sentence.

Atlanta woman continues fight to close city jail

She’s been arrested dozens of times since, most recently in 2008. Winn says she became the victim of a cycle. Unable to find a job because of her criminal record, she says, she kept shoplifting to stay afloat.

“I am that repeat offender that the judges talk about and, people say, needs to be in jail for the rest of their life,” Winn said. “My last arrest, I asked my attorney if I could speak with the judge. I told the judge, ‘Every time I stand up here before you, do you think I like it? It’s degrading. It’s humiliating. It’s embarrassing. All I need is a job where I can say I’m formerly incarcerated and not worry about getting fired.”

Since she found one, she hasn’t looked back.

“There is no data that correlates public safety being increased and crime doing down because we build more cages,” said Devin Barrington-Ward, founder of the Black Futurists Group. “In fact, we’ve seen the opposite. More people get tied up in the criminal legal system. They’re robbed of opportunities. They can’t go to college because they’re not eligible for financial aid. And [they] have to turn deeper into underground economies and criminal activity so they can survive.”

THE FIGHT TO CLOSE ACDC

“Leaders from Atlanta go all over the world … to build up this image of Atlanta as a Black mecca,” said Tiffany Roberts of the Southern Center for Human Rights. “But there are tremendous racial disparities that are perpetuated by the city jail. Many of us have bought into this idea that we address all harm through the criminal legal system. And we don’t think about what happens to a person’s chances of employment when they have an arrest record or conviction record."

In the discussion about criminal law reform, community advocates in Atlanta have focused on ACDC specifically – or, as they called it, “The Beast.”

In a 2015 article in Creative Loafing, Winn stands in front of the detention center with a sign saying, “CLOSE THE CITY JAIL.” But the efforts, she says, met resistance.

“Nobody was listening,” Winn said. “So we stopped talking about it, and we said, ‘We’re gonna starve the beast.’”

That meant fighting for measures to reduce the jail’s population. Some inside City Hall were willing to fight, too.

The year 2017 saw several moves dedicated to bringing down ACDC’s number of inmates.

In March 2017, the Atlanta city council passed a bill sponsored by then-councilmember Kwanza Hall to repeal 40 “quality of life” ordinances.

In October 2017, Mayor Kasim Reed signed an ordinance that eliminated jail time as a penalty for possessing an ounce or less of marijuana. That same month, a pre-arrest diversion program, now known as the Policing Alternatives & Diversion Initiative, began as a local pilot program to provide social services in situations that might not require police intervention.

Still, the jail continued to house hundreds every night – typically between 400 and 600 people.

DOWNSIZED BUT NOT CLOSED

In 2018, Mayor Reed’s tenure ended, and a new mayor – Keisha Lance Bottoms – took office.

“We met with her,” Winn said. “We had the kind of conversation that you and I are having. We had the conversation about people in the jail. We talked about how that impacted her life as a young girl.”

Indeed, Mayor Bottoms would write an opinion piece for CNN in July 2019, describing how police officers raided her family’s home when she was eight years old. They arrested her father, who served three years in prison.

“It was,” the mayor wrote, “the death of our family.”

Barely a month after her inauguration, Mayor Bottoms signed legislation to eliminate cash bail for nonviolent arrests. This meant people would not be held pre-trial at ACDC simply because they couldn’t afford bail.

Months later, when then-President Donald Trump came under fire for separating migrant children from their families, the mayor responded by refusing to accept any more ICE detainees. She ended the contract for good in September.

During the mayor’s first year, at its highest, ACDC averaged 488 inmates per night during the month of April. That December, the average had fallen to 92.

A few months later, the mayor decided it was time for the beast to close.

On May 28, 2019, Mayor Bottoms invited Winn, Barrington-Ward, and numerous criminal justice reform advocates to stand beside her at the jail as she announced and signed legislation to “reimagine the Atlanta City Detention Center.”

“As we transition out of the jail business in the city of Atlanta,” Mayor Bottoms said, “it doesn’t mean we are soft on crime. It means we are taking the proactive step of being one step ahead of crime in our city.”

Mayor Bottoms then introduced Winn, who received applause from the advocates around her before the mayor could finish her introduction.

“[This is] to transition the culture of the old Atlanta into a new Atlanta that embraces and supports its underprivileged communities,” Winn said from the podium. “When we fight, we win. And we won.”

It was a historic day. Headlines on websites claimed the city was closing its jail.

But it hadn’t. Two years later, it still hasn’t. And advocates now worry it won’t.

THE FIGHT TO KEEP IT OPEN

Standing behind Mayor Bottoms and the many advocates that day at the jail was someone who vehemently opposed the idea of the city jail closing.

“It was a unique position I was in,” Fulton County Sheriff Patrick Labat said.

In 2019, Labat was the Chief of Atlanta’s Department of Corrections. In short, he ran ACDC. And he was proud of it.

“ACDC was built in a humane fashion,” Labat said, “with humane thoughts in place about, ‘How do we treat people better?’ The worst thing that could happen is that it could sit there and be shuttered … and then have to spend more money to reopen it.”

Labat is one of several public officials campaigning loudly to keep the jail open – and fill it with more people. He agrees with little of what advocates like Winn, Barrington-Ward, and others believe about criminal justice.

“I come from the era of Red Dog” – the since-disbanded Atlanta police unit notorious for its aggressive approach to drug crimes – “and, ‘Take a bite out of crime,’” Labat explained.

And now? “There’s the perception that Atlanta’s the place to go because you won’t be held accountable for your crimes," Labat said.

His outlook has gained traction and popularity in recent months. It’s because of a series of events that began shortly after the mayor’s announcement.

ATLANTA CRIME SPIKES

In the second half of 2019, members of the Reimagining ACDC Task Force met to discuss potential changes to policies, programs, and, of course, the building itself. The city brought in Deanna Van Buren and her team at Designing Justice + Designing Spaces to develop new concepts for the space. The idea took hold of a Center for Equity, which could offer everything from reentry services to child care to workout and exercise rooms. It could also house many of the nonprofits who work on the ground to help underserved Atlantans.

The task force held five meetings and scheduled a sixth and final one for March 2020. That meeting never happened.

By that point, the city – and the world – were dealing with something much bigger. The COVID-19 pandemic affected every person on the planet and stopped an uncountable number of plans from taking shape. It also set off a crime spike in Atlanta that has been the catalyst for a new line of thinking on criminal justice reform.

From the first half of 2020 to the second half, crime in Atlanta rose 25%. Violent crime rose 35%. And homicides rose 63%. Similar spikes occurred – and continue to occur – across the country, but that meant little to those in Atlanta who suddenly felt less safe. News reports focused on street racing and gunshots at major malls. Voices rang loudly from the city’s affluent neighborhoods like Buckhead.

By January 2021, crime was – next to COVID-19 – the most pressing crisis facing Atlanta. And when the city council’s public safety committee met that month to discuss the future of the city jail, the thinking surrounding that jail had changed drastically.

“What a difference a year makes – like, 100 percent,” Councilmember Marci Collier Overstreet said. “With the rise in crime, I think we need to explore all options.”

“We’re experiencing the worst crime wave in a generation,” Councilmember Howard Shook said, “and I want to make sure the questions are asked.”

“What I don’t want to do,” Councilmember Cleta Winslow said, “is send a message to the broader country that we are not a law-and-order city. Other people across the country are listening, especially the criminals. Criminals know where to go when they want to do their stuff.”

REPURPOSING FOR COUNTY OVERFLOW

Suddenly, the idea of closing a jail – even one that only housed low-level offenses, not the kinds of crimes that had become everyone’s focus – made far less sense.

Labat, who took over this year as Fulton County sheriff, saw a different use for ACDC: as a place to house the overflow at the county’s jail on Rice Street. In his first week on the job, he announced intentions to buy Atlanta’s jail. When that hit a wall, he proposed the city house hundreds of Fulton County inmates in its mostly empty cells.

That idea has gained traction with many on Atlanta’s city council.

“I do not support closing our corrections facility,” said Councilmember Bond, the only councilmember to vote against the initial legislation to reimagine ACDC. “As long as you have a police department, you’re always going to have the expense of corrections, whether you pay for your own facility and you’re paying someone else. I think we ought to be able to use [ACDC] in tandem with our partners at Fulton County to help them alleviate some of the overcrowding.”

“I would allow Fulton County to utilize the jail on a temporary basis,” Council President Felicia Moore said, “and then decide what you want to do with the jail in the long term. Tearing it down seems to be wasteful. The taxpayers have spent and invested and paid for that building, and it’s perfectly good to use.”

Councilmembers have encouraged Mayor Bottoms to negotiate with Fulton County. Advocates for closing the jail have pushed back, begging the mayor to reclaim the narrative.

"When [Mayor Bottoms] speaks on the issue, I think she speaks very clearly and forcefully. Unfortunately, she just hasn’t spoken about it enough," explained Xochitl Bervera, the co-founder of Racial Justice Action Center.

“This was Mayor Bottoms’ resolution,” Roberts said. “It was Mayor Bottoms who said Atlanta will no longer be in the jailing business. So, I believe it’s Mayor Bottoms’ role to lead on this.”

And does the mayor still want to close the jail?

“I don’t think she’s sure,” Roberts said.

MAYOR KEISHA LANCE BOTTOMS

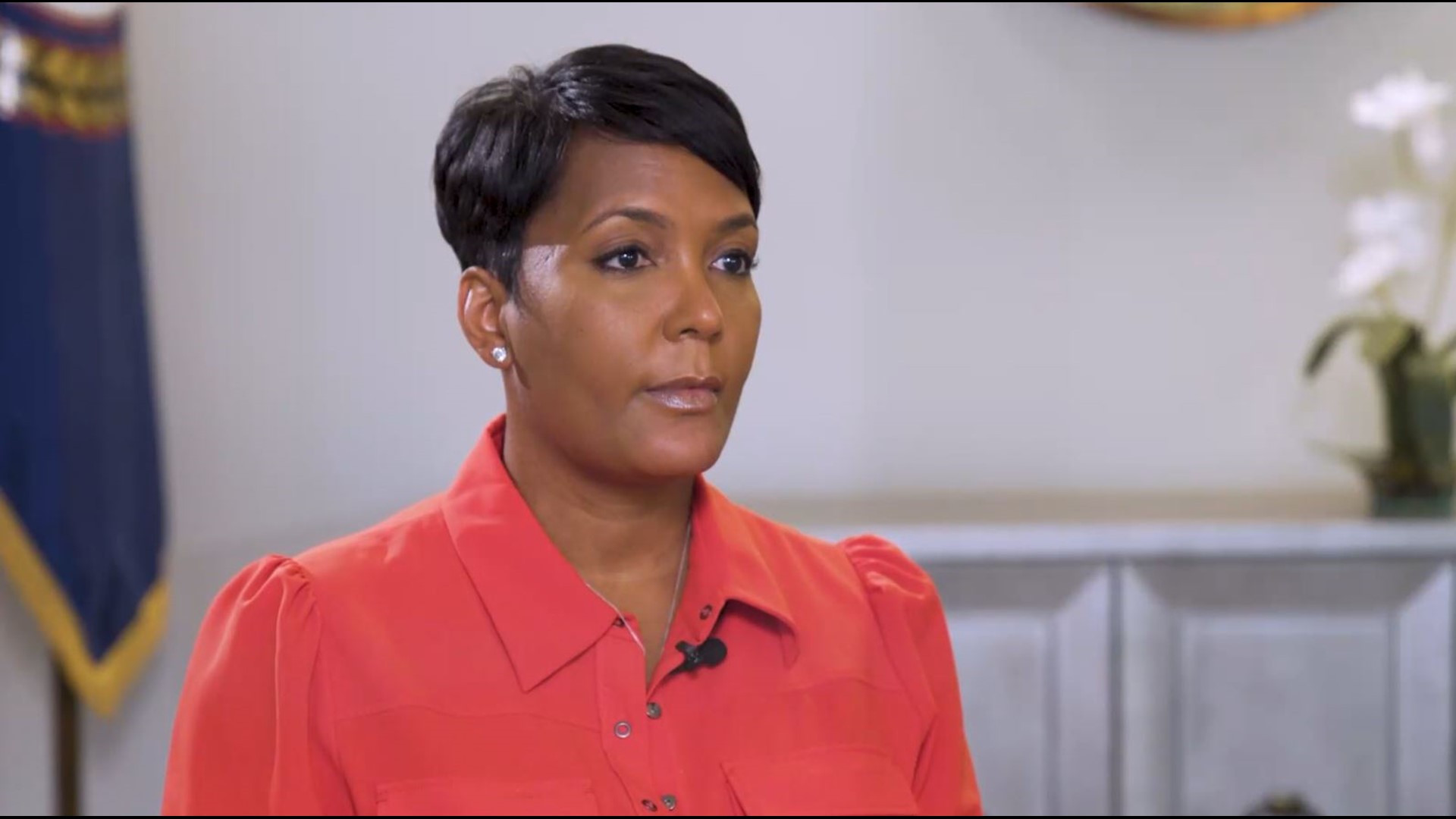

Sitting from a room in City Hall overlooking a downtown street, the mayor of Atlanta wants to make it clear: She’s sure.

“For me personally,” Mayor Bottoms said of the detention center, “it was this symbol of mass incarceration. I know what it’s like to have a family member held in prison because I experienced that with my father. But I have so many personal stories of having family members locked up on something very simple. It creates this domino effect. You can’t pay a traffic fine, so you’re held in jail, and then you lose your job, so you can’t pay rent or child support. It creates this never-ending cycle that’s not just a story of my experiences but of many people in the community, especially the African-American community.”

It’s the middle of April 2021. Privately, the mayor is weighing whether she should run for reelection. Publicly, she remains resolute on why criminal justice reform remains necessary, even as crime spikes in her city.

“It was a big moment,” she said of her announcement in front of ACDC back in 2019. “We had so much support and goodwill for it. People were talking about criminal justice reform and wanting to do things differently. And unfortunately, it seems, with the COVID crime wave, we’ve almost done a 180 from that moment, back to the 1980s and 1990s model of, ‘Lock ‘em all up.’”

For Mayor Bottoms, it comes back to her original position: reducing crime doesn’t happen by putting people behind bars. It happens by preventing the circumstances and lack of opportunity that leads to crime for so many.

On this and so many other matters, the mayor remains in lockstep with the advocates who have pushed to close ACDC since before her administration.

As for how to move forward? The matter gets grayer.

She cannot unilaterally close the jail. She needs the city council to approve it. The council’s public safety committee has held her justice reform plan, meaning it won’t receive a vote from the full council for the foreseeable future. Meanwhile, it continues to push the mayor to negotiate with Fulton County, something she said she has begun doing. The city has offered to take in 150 county inmates whose sentences are ending and are preparing for reentry.

As to the claim from advocates that she hasn’t put herself out there as much as she did in her first 18 months? Mayor Bottoms quickly pushes back.

“I talk about it all the time,” she said, “but I don’t dictate the news cycle. When everybody on the globe is dealing with a pandemic, that’s what the news cycle and reporters will ask me to speak about. There are a number of issues and challenges I’m speaking on at any different time. The jail is a very important one, but I speak to it with every opportunity I have.”

She holds little patience for those who now conflate the rise in crime with the future of the jail.

“Part of it is intentional misinformation,” Mayor Bottoms said. “Sheriff Labat is a jailer. Think of a prison warden. That’s what he does.”

In the end, Bottoms says she believes in the importance of closing the jail – but also in what has already taken place.

“Our administration has done more than any administration in the history of this city to get us where we are on criminal justice reform,” said the mayor. “For our advocates, it’s not happening fast enough. But we’ve made progress, and I can tell, before I became mayor, there was no progress.”

ACDC IN LIMBO

Weeks later, Mayor Bottoms surprised the city. She announced she would not seek reelection. A new mayor will take over in 2022.

It leaves the future of the jail in serious limbo.

There has been no progress on the mayor’s justice reform plan. Momentum has stalled. Life in Atlanta has begun to return to a new normal as COVID-19 cases have dropped, but crime remains an overarching issue.

At the mayor’s press conference, she was asked about the future of the Atlanta City Detention Center. Will she be able to see through the most transformative aspect of her criminal justice reform plan?

“I hope so,” she responded. “But leadership is about sometimes gracefully passing the baton.”

Even before the mayor’s announcement, advocates like Winn and Bervera acknowledged the long-term arc of their mission.

“Bold, progressive change requires a lot of course,” Bervera said. “It requires a lot of factors to come together at the same time. [But] if you have a building built as a jail, at some point forces will move to fill them up with somebody. And I think that’s the danger. If we do not close and demolish this jail, will it be filled back up with some other group of people who are considered expendable?”

For Winn? The days are grueling.

“I’m burned out, running on fumes,” she said. But her purpose remains.

“I’ve given the system a lot of my time,” Winn explained. “But it started out as one. One arrest led to all of those things, and all I needed was a service. I needed someone to give me a job, and today, instead of me working and meeting you, I would have been retired, sitting home somewhere, maybe rocking babies or grandbabies.

"But I'm working."