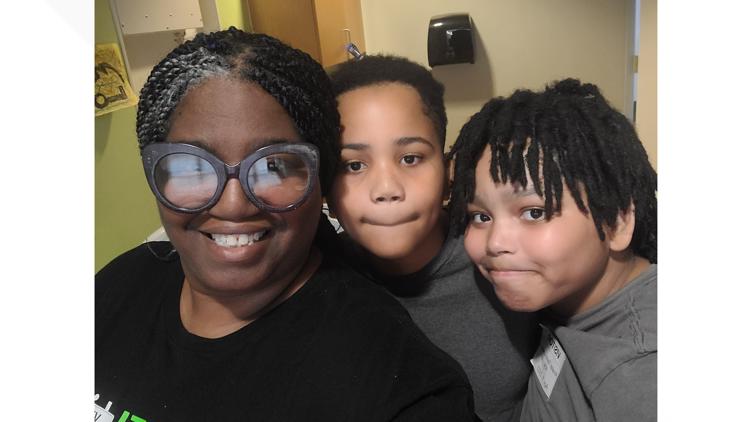

ATLANTA — Kelli Lewis loves to share pictures and videos of her sons, Ahav and Analiel. Ages 14 and 13, the images tell the story of two boys who love to sing, dance, and draw.

“That was probably a subconscious move to send you the good times,” said Lewis.

Lewis has plenty of other videos and pictures, moments when Ahav seems lost in another world that provokes violent outbursts or experiences hallucinations he can’t shake.

“These are highly creative, beautiful, loving, caring, funny, silly little boys that just happen to have a mental illness," she said.

Lewis' interview was done via a video Zoom call because after 20 years of living in Georgia, she has moved out of state to find treatment for her sons. They both have autism and severe mental health disorders. It’s a combination Georgia’s Medicaid system struggles to treat but Lewis doesn’t understand why.

“This hospital, this program that my son was sent to that has fully integrated care, he was placed there by DCH, by Georgia Department of Community Health,” she explained. “Which means Georgia is completely aware that there is a gap, and they know a place that fills the gap.”

The story continues after the gallery

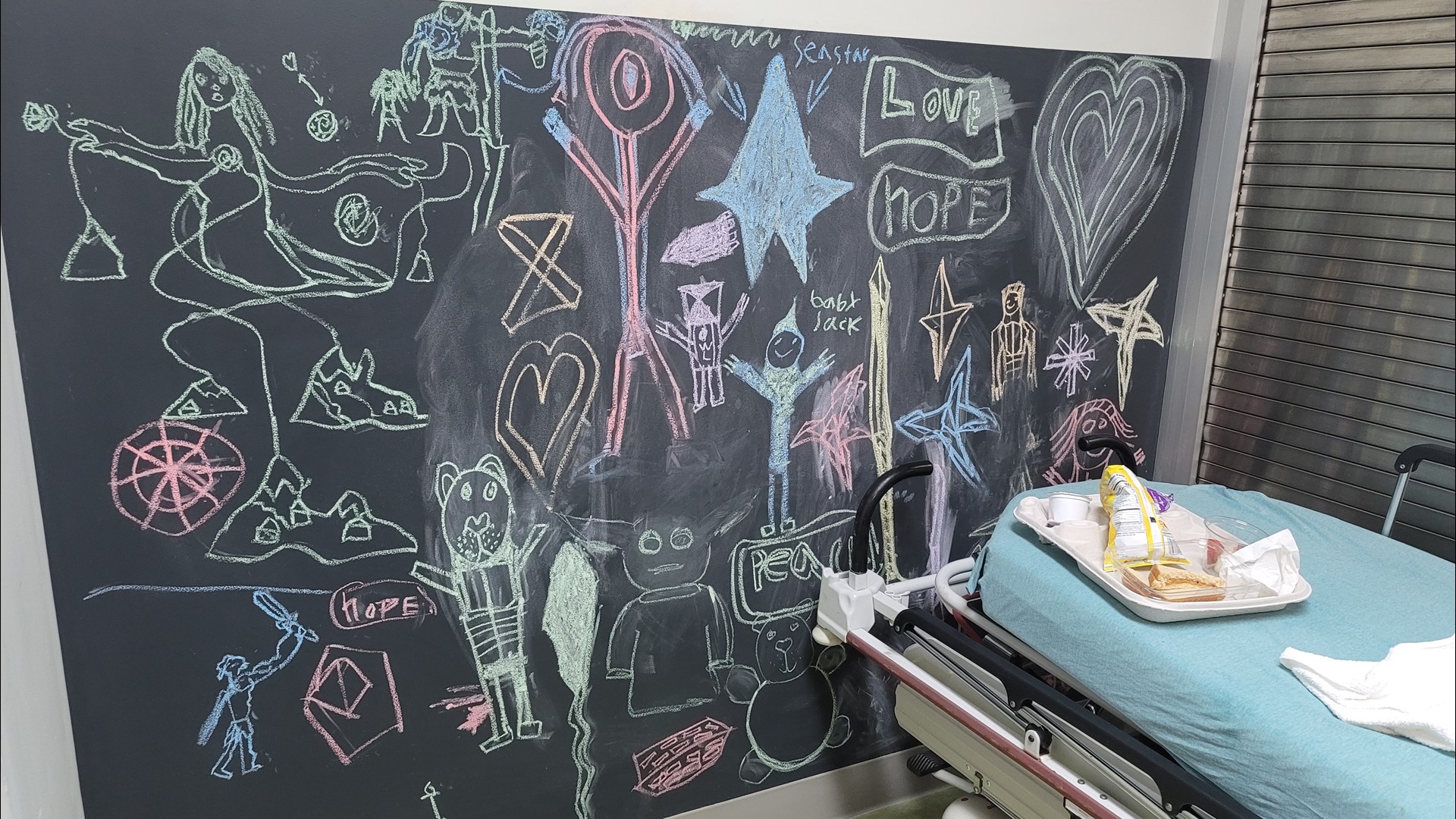

Ahav and Analiel | PHOTOS

That’s why the Georgia Advocacy Office, GAO, is working with the National Health Law Program, the Center for Public Representation, and attorneys with two other law firms, Kilpatrick Townsend & Stockton and Duane Morris. Together, the coalition filed a class action lawsuit in the U.S. Northern District Court against three state agencies, the Departments of Community Health, Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities, and Human Services, which facilitate the patchwork of programs.

Joe Sarra, an advocate who tries to help families navigate the system, said there are three large bureaucracies that impact whether these children receive care, but no one number to call. It's a system he describes as fragmented and ineffective.

“If you take children that are ages 6 and 7, which are critical developmental years, and you’re not providing them access to medically necessary services that they have a right to, you’re essentially stunting their growth,” said Sarra.

The lawsuit names four plaintiffs, but as a class action, is expected to represent more than 40,000 children on Medicaid who have a developmental or intellectual disability and/or significant mental health need.

Of the named plaintiffs, one is a 15-year-old living in Fulton County, admitted to a psychiatric institution 16 times in one year.

Throughout his young life, he experienced suicidal ideation, hallucinations, self-harm, and emotional instability, leading to emergency room visits and stays in psychiatric hospitals. His mother said she gave the state temporary custody in the hopes of obtaining better services so he could return and remain safely at home. However, according to the lawsuit, he ended up living in a staffed hotel room and then institutionalized.

Ruby Moore, the executive director of the GAO, said the lawsuit is about protecting children from abuse and neglect.

“We think that probably the worst abuse that’s happening this day is children being ripped out of their homes, taken from their families and their siblings, and then relegated to endless cycles of going into emergency rooms, being sent to institutions unnecessarily and other segregated places,” Moore said.

She also said the GAO has had some discussions with representatives from the state agencies involved but feels they lack urgency in truly reforming policies and funding to meet the needs. Moore added, “Enough talking. It’s time for action.”

The GAO referenced 11Alive Investigator Rebecca Lindstrom's multi-year series #Keeping in an August 2023 letter to the state as further support for reform. The series focused on children with complex mental and behavioral healthcare needs, fighting a system that seemed intentionally ill-equipped to help.

11Alive's Keeping: How Georgia forces child abandonment (the story continues after the video playlist)

Devon Orland, the legal director for GAO, said there’s plenty of evidence to make the point.

“It's not going to be difficult to find evidence because the state itself has created its own evidence against itself. They blame each other,” Orland explained. “They've written reports, they've studied, evaluated, they've come up with solutions and not implemented things.”

In a letter written to three state agencies asking for meetings to outline tangible reforms, the GAO alleges some medically necessary services are not covered or exist only on paper.

Lewis said her sons have been hospitalized 65 times, repeatedly treating only surface issues, and there are virtually no options for care when they come back home. She remembers calling to confirm an appointment set up by a mental hospital treating her son.

“They'd never heard of us. They don't treat children,” she recalled. “They were basically a drug and alcohol treatment center. So now you gave me a fake discharge appointment?”

Lewis's account isn't the only one.

“One young man I worked with was institutionalized 20 times within 365 days,” said Sarra. “That is not therapeutic.”

What the lawsuit seeks

Under the Medicaid Act, the state is required to comply with EPSDT, Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic and Treatment. It’s a lot of words that essentially mean the state must provide comprehensive and preventive health care services for children under age 21 who are enrolled in Medicaid.

As part of the Americans with Disabilities Act, those children with a developmental or intellectual disability are entitled to have those services in the most integrated setting appropriate. That means community-based services, not institutionalization.

To achieve those goals, the GAO said Georgia needs to start by improving three things.

Read the full lawsuit at the bottom of this story.

Intensive case coordination

First is intensive case coordination.

“Families don’t know where the front door is. They don’t know how to find the services. They get a phone number upon discharge from an ER, mobile crisis, or residential treatment facility. The phone number is bad. They don’t know where to go. So you need somebody (to) say, not only do I know where to go, I’ll make the call for you,” explained Orland.

In-home services

Second, in-home services.

“They follow the kid, the child, not only in the home but in the community, a trained behavioral specialist that understands how to work with a child,” said Sarra.

11Alive profiled one family whose son, Bradley, had been in an out-of-state residential treatment facility for more than four years because the state wouldn’t approve or couldn’t find a therapist to work with Bradley at home. The family has two younger children and Bradley’s behavior put them in danger.

The state does offer some in-home supports, but they are available only to children with certain diagnoses and for a limited number of hours and time.

Mobile crisis units

Finally, the GAO wants to see increased access to mobile crisis units. 11Alive Investigates has talked with families who say they’ve waited for hours to get a response, leading them to call the police or go to the ER instead.

The GAO said as a result, many children end up in crisis stabilization units or private residential treatment facilities when trained intervention could have de-escalated the situation and allowed them to remain at home.

Because Lewis has moved, she is not part of the class action lawsuit. But her experiences help explain why those still in Georgia believe something needs to change.

Lewis has asked us not to say where they’re living now. But Ahav said the new hospital, in this new state, has already given them new hope. The GAO doesn’t feel families should have to move to get it.

“Georgia has been doing what they're doing for a very long time,” said Orland. “We’ve written letters, we've talked to people - we've tried, and we're really left with no other solution at this point. So here we go.”

Response to lawsuit

The state declined to comment on the lawsuit.

The National Health Law Program

"The National Health Law Program is committed to ensuring that children with significant mental health needs in Georgia receive the services that they require to grow and thrive in their communities. NHeLP has a long history of working to improve children’s access to mental health services, and the situation in Georgia is dire. The children we represent routinely experience avoidable mental health crises. They desperately need, and are entitled to receive, the services we are seeking. Despite efforts to resolve these longstanding problems, effective action has not been taken. These children need help now." - M. Geron Gadd.

Center for Public Representation

"The Center for Public Representation recognizes that after the pandemic, especially for children from communities of color, Georgia’s failure to provide legally required intensive home-based mental health services has resulted in the deterioration of children’s mental health conditions and their institutionalization. CPR has successfully litigated and settled similar cases in a number of other states which have resulted in the dramatic expansion of in-home mental health services, allowing children to remain with their families, in their schools and in their communities," a spokesperson said.

Read the full lawsuit below:

More on 11Alive Investigator Rebecca Lindstrom's 'Keeping' series: