Mom says she left note with abandoned child, police never found it

A teenage boy left at a hospital in December 2019 triggered 11Alive’s investigation into child abandonment. His mom says there’s a lot we don’t know about that day.

This is part of a series of reports called #Keeping. The reports expose gaps in our healthcare and support systems that lead to child abandonment. The children's parents shared these painful videos to educate others and raise awareness.

#KEEPINGSHELDON

Diana Elliott admits she did something drastic but says she didn’t abandon her son at Grady Hospital. She left him with a note.

Elliott says it included his name, birthday, and a simple message: my mom needs help.

The problem, nobody found that note and Sheldon, who has Down syndrome, is non-verbal.

“I didn't take it to account he could drop the letter, roam out of the door, roam out in the cold,” explained Elliott, reflecting back on her decision.

Sheldon’s mom waited nervously in a motel room with her three other children for nearly a week. Her children grew restless wondering what was going on.

“I'm thinking, oh, they're going to call me. They're going to say, ‘she needs help’ and they are going to come help,” she said.

CHILD ABANDONMENT IN LEGISLATIVE SPOTLIGHT

We shared our stories of systemic gaps and heartbreak leading to child abandonment with legislative leaders in Georgia. We showed them how workforce shortages, mental health parity, and the denial of medically necessary services all play a role.

“There’s something fundamentally wrong with a system that lets that happen,” Georgia Speaker of the House David Ralston said.

It is the system Georgia’s leaders in both the House and Senate told 11Alive they are committed to fixing.

“We’re using state-appropriated dollars to fund a lot of these programs. And certainly, those are proper questions to ask. Those are proper conversations to have,” Lt. Governor Geoff Duncan said. “I think this is just a personal issue for everybody, they just don’t know it yet.”

Indeed, we found bipartisan support among key lawmakers, many of whom have formed a mental health caucus.

In a written statement, the House appropriations chair, Terry England, said “behavioral health issues will take up much of our time in the upcoming session,” adding, “Why? Because it is the right thing to do.”

The House minority chair James Beverly also said he is “hopeful in this next session to address mental health disparities, lessen the drain on state resources, and child abandonment issues.”

Lawmakers supported Speaker Ralston’s request for an additional $58 million in the 2022 fiscal year budget to increase access to mental health services in the community and schools through the Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities. It also set aside $7 million for a behavioral health crisis center for individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities.

This year, he’s already proposed another $20 million to increase funding for law enforcement crisis intervention training, establish more crisis beds and expand mental health accountability courts.

Advocates applaud the funding for more crisis beds but ask, once stabilized where is that person supposed to go? A concern in Georgia is the limited availability and types of step-down services to help transition back into the community, thus creating another crisis.

That's why Lt. Governor Duncan says lawmakers will have to tackle the problem from multiple angles.

“I don’t think we start in one lane and I think maybe that’s what we’ve seen play out in the past. We’ve started down a lane, singularly focused on a regulation or appropriations or legislative change. I think we need to move with equal amplitude on all, so that we arrive at the finish line as quickly as we possibly can,” he said.

Ralston agrees. He says lawmakers need to show up in January ready to identify all the barriers and knock them down.

START THE WRECKING BALL

The Reveal investigator Rebecca Lindstrom traveled to Ohio where Elliott is now living near her children to find out where that wrecking ball should start.

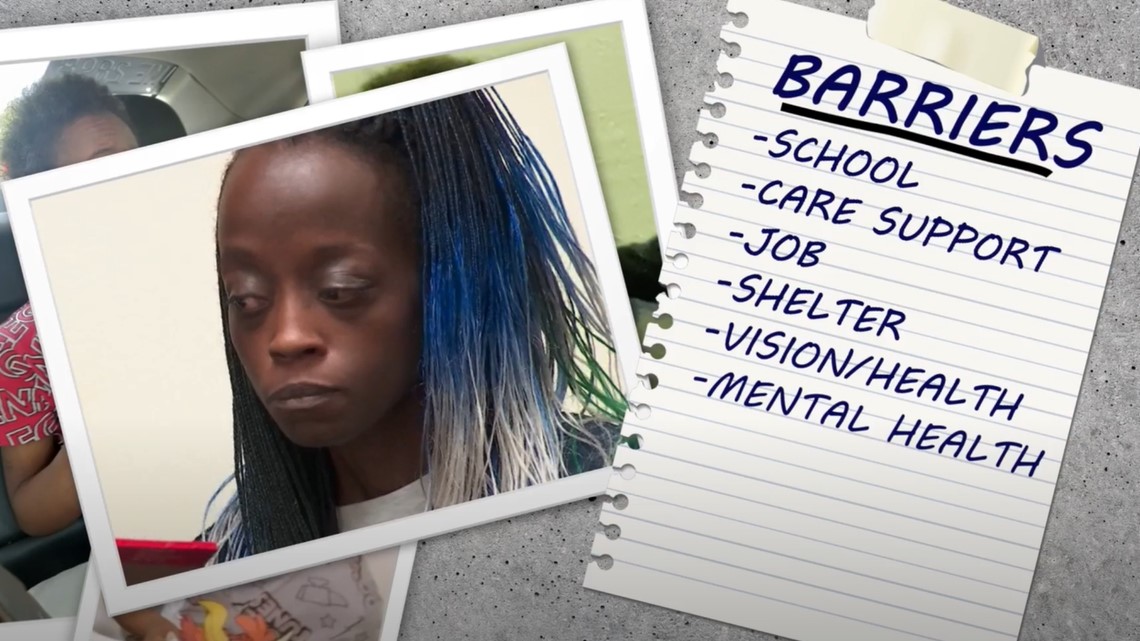

Elliott says when she moved her children to Georgia to break into the movie biz, she had no idea services for children with special needs varied by state. Her first barrier– the school.

“He would have had 22 kids in the classroom,” Elliott explained. “Sheldon has never had that setting. That was making my paranoia go off so much. I was like, I don't know that he'll be OK in that setting.”

So, Elliott kept him home. That’s when she ran into another wall. In Ohio, for a few hours each week, Sheldon would get what’s called respite care. That’s when someone comes in and watches Sheldon so Elliott can get a moment to herself. It’s time so that parents can run errands, go to their own doctor’s appointments or just reconnect with a friend to maintain their own mental health.

Without that break, Elliott says it was impossible to go to auditions or get a job. No job, no credit... no money for rent. When money for a motel ran out they went to the airport for shelter.

“That was bad. I clearly, our suitcases were on the benches and we're sleeping in the airport and we're keeping a low profile, you know, during the day, at night it’s more obvious,” she said.

While Elliott’s kids did their best to go with the flow, Sheldon struggled with the change and his vision.

“He has a nystagmus. So, when we're looking at still pictures, he's looking at a picture that's moving like this,” Elliott said, waving her hand to imply motion as she spoke.

If a space is too open or too high, he gets scared. Stairs are a challenge.

“That’s when he throws his tantrum and he gets really aggressive in a couple of times he even pulled my hair out,” she said.

And there was one more big barrier. Elliott, needed help too. Since childhood, she’s struggled with PTSD, anxiety, and depression.

“I like to call myself the Phoenix. I grew up in foster care and there's a whole lot in my jacket where I can be coo-coo. But I use it as strength,” she said with a laugh.

But strength has its limits. According to data provided by DFCS, the state takes custody of more than 600 children a year because of the parent’s mental health or substance abuse. For Elliott, the breaking point was an abusive relationship. She escaped, moving her family back into a motel but Sheldon refused to go inside.

“He fought and fought and he fought,” she recalls. “But I don't know, that day I didn’t have any more fight in me.”

So instead of forcing him inside yet one more motel, she left him, for the moment, somewhere she thought he would be safe.

Back in Ohio, two years later, Elliott and her children say they have more family support and access to things Sheldon needs. She says she’s apologized to him over and over in song, hugs, and simply time together. Their home is humble, yet beauty is everywhere.

“I don’t want all of this to be for nothing,” Elliott said.

While police never found Elliott’s note, lawmakers say they’ve heard her message.

“This is not going to be a one-session fix to this system. This is going to be a multi-year effort,” Speaker Ralston said. “Have a little bit of patience because this is a big problem. Government don’t do well with tough problems. But we’re going to do well with this one.”

This story was told as part of a 2020 Data Fellowship with the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism.

The Reveal is an investigative show exposing inequality, injustice, and ineptitude created by people in power throughout Georgia and across the country.