TUCSON, Ariz. — Gary McGinnis struggled with depression and drugs for decades. Now, more than 13 years clean, he reflected on what made the difference.

“I call it the gift of desperation," he said. "There’s a reading that at the end of the road we find that we can no longer function with or without. We’ve got to find a new way to live. So it was about seeking that out. What is this new way to live?”

His question is our question. Communities right now are at the end of the road, desperate to figure out how to actually help those with a mental illness.

11Alive investigators met McGinnis in Tucson, Arizona, while studying a concept gaining international attention. It’s called No Wrong Door.

In Tucson, it’s a system, not a slogan. Every community has 911, police, and crisis care. What makes Tucson different, is how they use them.

“It’s kind of like Rome. There are many roads that lead here,” explained Margie Balfour adding that no road is the wrong road. “Our whole system really adopts this no wrong door philosophy.”

Balfour helps manage Tucson’s Crisis Response Center, or CRC, which is considered the heart of the system.

NO WRONG DOOR

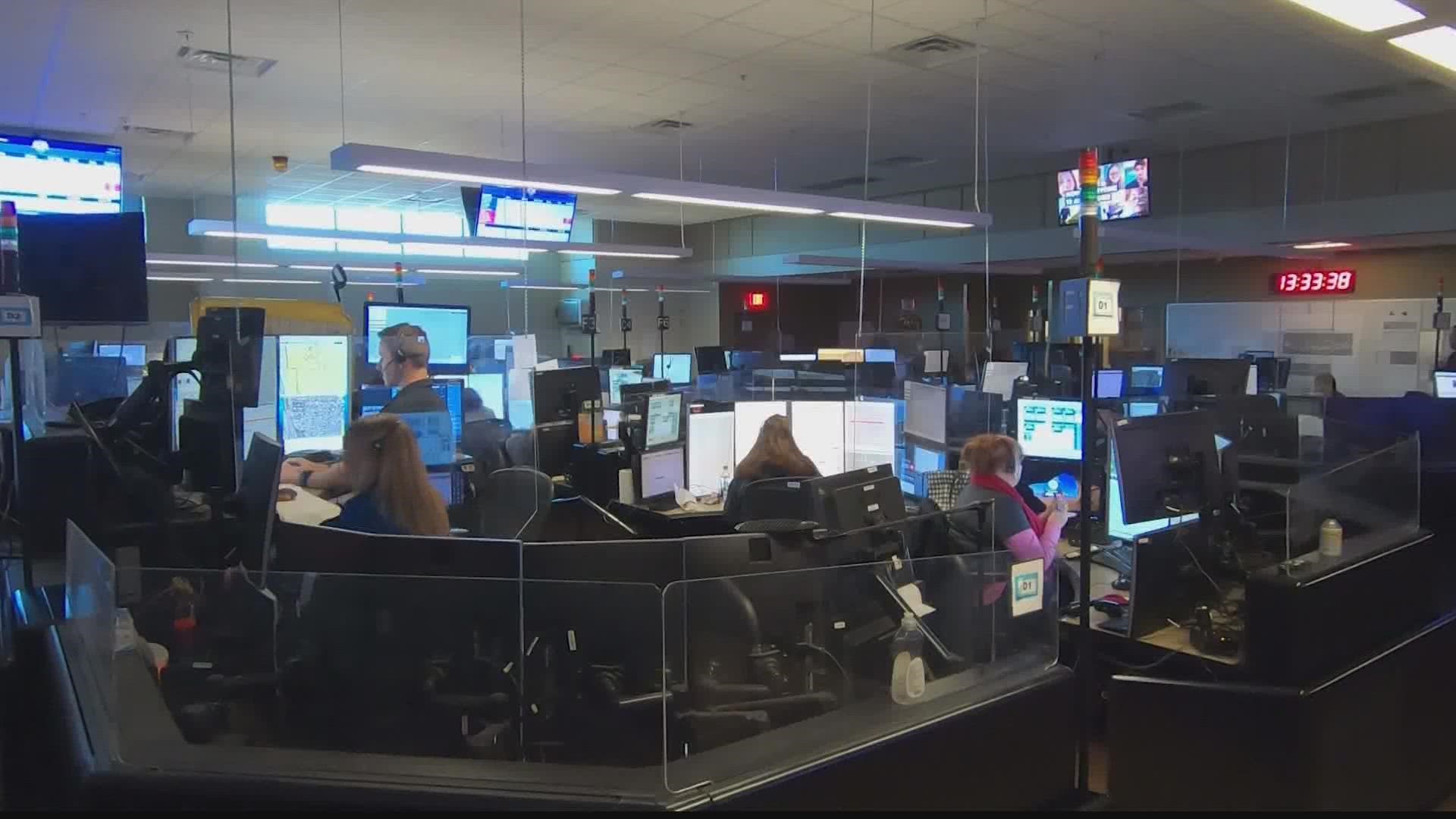

For many, the first door they reach is 911. In Tucson, a mental health clinician is embedded in the process. If a call warrants a mental health response, rather than police or EMS, the call is directed to that clinician.

If police are still needed, Tucson said it has made crisis intervention training, CIT, a priority. About half of its police force has received the training.

NAMI of Southern Arizona would like to see that training for every police officer.

“Education is the gateway to understanding and empathy,” training and resource specialist Lisa Cole said. “It’s very traumatizing to already be experiencing severe mental health symptoms and then see uniformed officers come in with guns and their weapons. That’s going to intensify the situation and make it worse.”

It’s one reason NAMI partners with those giving the training to talk with officers about what it’s like for the person in crisis.

FOCUSING ON CRISIS PREVENTION

That awareness and education led Tucson to go a step further with special teams focused on crisis prevention.

11Alive Investigator Rebecca Lindstrom followed one time as they traversed Tucson, transporting one woman for a mental health evaluation after allegedly failing to follow her court-ordered treatment plan.

“Your case manager, if they feel like there’s a concern with something going on with you or they feel like you’re not following the treatment plan, they can send a form to the court that suspends your outpatient status,” Officer Joshua Godfrey explained to the woman.

Tucson Police Sergeant Jason Winsky said programs like the mental health support team should be part of every community’s discussion around parity.

“If you look at a police department that has a DUI squad or a gang squad or any other specialty squad, why wouldn’t you have this one?” Sgt. Winsky asked.

He said due to their specialized training, only once in eight years did the team require the use of force. They’ve arrested fewer than 10 people.

Sgt. Winsky said several years ago the police department studied their jail population and found nearly two-thirds had some type of mental health diagnosis. They needed treatment, not jail time.

“You hear chiefs and sheriffs saying I don’t have a place to take this person," he said. "The value of the 'no wrong door' policy here at the crisis response center is that when my team and I are out in the community, that I don’t have to worry about that.”

Balfour said it’s no surprise that a year after the CRC opened, their data showed the number of inmates with a serious mental illness decreased by half and crisis ending up in the ER dropped by 80%.

'WHATEVER YOUR CRISIS IS, WE CAN FIGURE IT OUT.'

The CRC is open 24 hours a day and is accessible to anyone in the community regardless of insurance. The needs of those who come through the doors range from an expired medication to a complete psychiatric break. Balfour said staff will never turn someone away.

Balfour said it's important that when people come to them through police, the handcuffs come off immediately if handcuffs are used at all. She said it is their staff that holds the key to signal they are there for treatment, not punishment.

“We don’t use any security staff," she said. "We take highly agitated people, we want the highly agitated. Those are the people who most need a specialized facility like this.”

It can take hours for an officer to drop someone off at the emergency room for an evaluation. At the CRC, it takes less than ten minutes.

“In my mind, it’s the bedrock of the work that we do,” Winsky said.

The CRC connects to a traditional hospital, a psychiatric facility and a court. Now, the CRC is going a step further, launching a program called Transitions.

“Whatever your crisis is, we can figure it out and help you find a direction from here,” McGinnis said.

McGinnis now works as a peer recovery support specialist at the CRC. His role has changed over the years from helping people connect to Medicaid or other services if eligible to now following people after they leave the CRC to ensure they stay connected.

“They open up more, they tell us more about it when they can’t believe sometimes 'hey, I was a person who was looking for cigarette butts in the gutter because I needed a smoke,'” McGinnis said. “Most people do want to talk. They want to be heard. So, our job is to listen and hear.”

The CRC didn’t exist during his decades of addiction and depression.

“I had actually robbed my little brother's bank account. I found his passbook, and I went through the money to buy cocaine,” he said. “I was homeless. My relationship had abandoned me. I suffered from depression. I tried to commit suicide.”

But, McGinnis said he’s grateful to have a place now where he can use those experiences to help others.

“We’re the ones that can show others it can be done," he said. "That change is possible."

Change for the person and the community in crisis.

#Keeping is an investigative series that exposes the gaps in Georgia's mental health care system that cause thousands of children to be surrendered to state custody.