There's been a lot of talk about lead in the drinking water lately. Some of that talk has actually turned into action.

Last summer, 11Alive wanted to know what school districts in the metro were doing to make sure the water coming out of their fountains and faucets was safe.

As Investigator Rebecca Lindstrom learned, not much.

After 11Alives's initial investigation into lead contamination in school water sources, the Cherokee and Clayton school districts sent written statements insisting their drinking water met all safety standards and that “anything built or installed since 1990, by code, was lead free.”

But in the following months, attitudes seemed to change as Lindstrom showed that wasn’t always the case.

Forsyth and Henry Counties now indicate they will test all of their water sources district-wide. Cobb and Gwinnett Counties have conducted some random testing, but Douglas County still insists there’s no need.

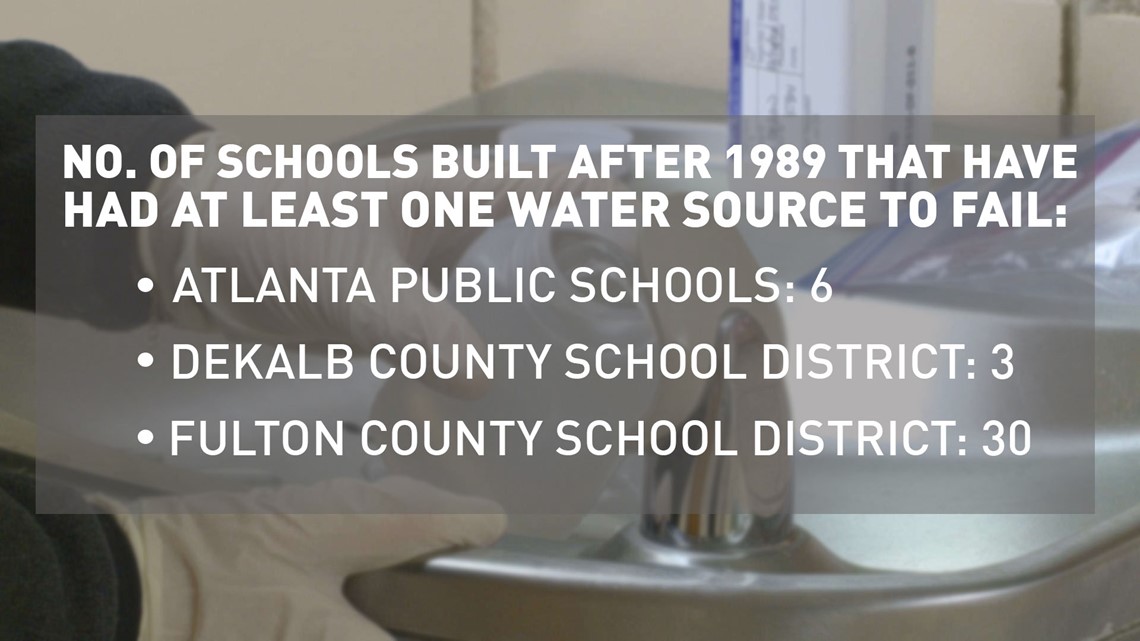

The Atlanta Public School System had already finished its testing when DeKalb County announced it would test all of the fountains and faucets throughout the district.

Initial testing in DeKalb could last until the end of the school year, but so far a spokesperson said they’ve finished 91 of their 148 facilities. Of the 2,439 samples taken, 3.7% were above the EPA action level of 15 parts per billion. The district has been able to remediate many of those water sources, and until they are fixed, the district stresses the water fountain or faucet remains off.

Fulton County Schools told Lindstrom last summer, the district only planned to test six schools, mainly older construction. But it, too, has since expanded testing district-wide. The results? Thirty schools built in Fulton County after that “lead ban” had a water source with high lead levels. Some of its highest results were found in the faucets that fill kitchen kettles.

“It’s basically something they can cook soup or stew or something like that in,” explained Joseph Clements, the Director of Facilities Services.

The water that came out of the kettle at Chattahoochee High was 23 times higher than the federal limit. The district was quick to note that the test reflected lead levels only in the first cup of water. Levels can drop quickly after that and a kettle uses gallons of water.

Still, Clements admits, he didn’t expect to find such high lead levels in the district’s newer constructed buildings.

So what’s going on? Despite all the rules on how the water is treated, the type of pipes that can be used to transport it and even the solder used to plumb it, until now, haven't been monitored as heavily. Regulators hadn’t paid as much attention to the lead in the valves at the end of the line. Basically, the faucet where the water comes out.

New valves can have 97% less lead in them than those made just three years ago. While not all valves are leaching lead, schools won’t know if they’re impacted unless they test for it.

Sen. Vincent Fort doesn’t believe testing for lead should be optional. He’s introduced a bill to require testing the water, not just at public schools, but also private schools and daycares.

“Lead poisoning is about as dangerous as you can imagine and when we’re talking about children, it’s especially dangerous,” Fort said.

Currently, there are no state or federal requirements for schools on municipal water systems to test their water for lead. However, on Feb.27, the bill proposed by Fort was passed in the Georgia legislature and will move on to the Senate for a vote. If it doesn't pass during crossover, it will die.

Given the risks and current test findings, Lindstrom tried to talk with the EPA about whether that should change. The EPA would not talk on camera, but did say they had sent letters to governors and commissioners highlighting the importance of testing, and that it was currently reviewing recommendations made by the National Drinking Water Advisory Council.

A spokesperson also added, “there is a compelling need to modernize and strengthen implementation of the rule – to strengthen its public health protections and to clarify its implementation requirements to make it more effective and more readily enforceable.”

If districts do decide to test, there is a cost, and only the community can decide if it’s worth it. Fulton County spent about $300,000 just on tests and found problems at 161 schools.

“The question is, can we afford to fix it," Clements asked. "We will find the money to fix it. Until we get to fixing it, all those water sources remain turned off and out of service.”

Here’s a look at the responses 11Alive received from metro school districts last summer and now:

Several school districts have tried to be as transparent as possible about their testing and the results. Both Fulton and DeKalb Counties set up hotlines to answer parent’s questions, but say they haven’t received many calls.

Does your child attend a Fulton County School? Click here to see the results from their classroom.

Does your child attend a DeKalb County School? Click here to see the results from their classroom.