911 is still broken, and rescuers may not be able to find you in an emergency.

As 11Alive Chief Investigator Brendan Keefe first showed in the Peabody Award-winning series Lost on the Line: Why 911 is broken, emergency calls routinely go to the wrong city or county – even if the caller knows where they’re dialing from.

Wes Price knew exactly where he was when he called in to report an accident with injuries in late March.

Dispatcher: Cobb County 911 what's the location of your emergency?

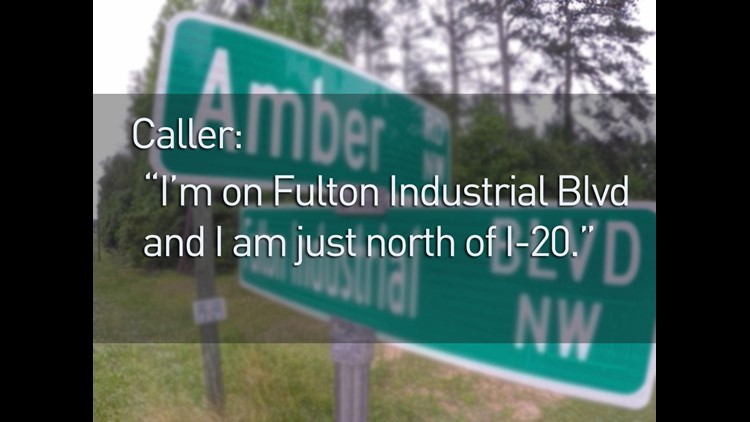

Caller: I’m on Fulton Industrial Boulevard and I am just north of I-20.

Dispatcher: Alright, hold on one second, you’re in Fulton County, you’ve got Cobb County. Let me transfer you to Fulton.

911 is still broken

Price's 911 call hit a Cobb County cell tower, costing 30 seconds before a transfer to Fulton County’s 911 center, and then yet more precious time to transfer to a third emergency call center in the city of Atlanta.

Fulton dispatcher: Atlanta, this is Fulton with a transfer? Caller advises that they’re on Amber Road and Fulton Industrial Boulevard and I’ll stay on the line as well.

Atlanta dispatcher: OK, Amber Road… and Fulton Industrial? That’s on Fulton County. Is this Fulton County?

Fulton dispatcher: This is Fulton County, but it’s showing Atlanta. That’s why I was calling, I said I was going to stay on the line.

Atlanta dispatcher: Oh, yeah. It’s coming up...

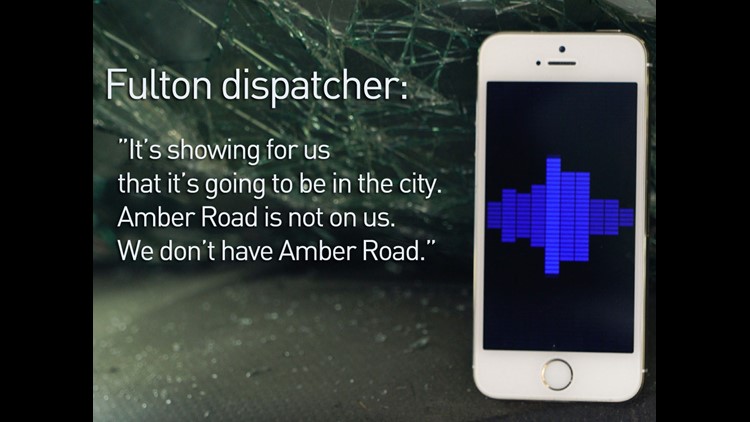

Fulton dispatcher: It’s showing for us that it’s going to be in the city. Amber Road is not on us. We don’t have Amber Road.”

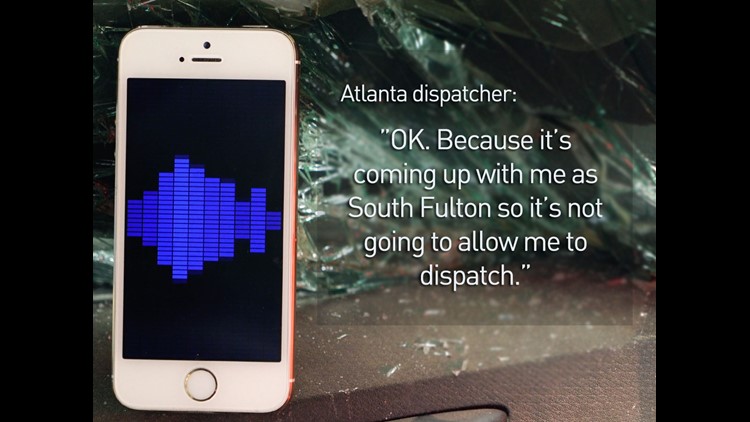

Atlanta dispatcher: OK. Uh.. because it’s coming up with me as South Fulton so it’s not going to allow me to dispatch.

“They were wasting time in my opinion,” Price said. “They were on the phone wasting time that mattered – could have mattered in someone’s life.”

AUDIO | Listen to the 911 confusion:

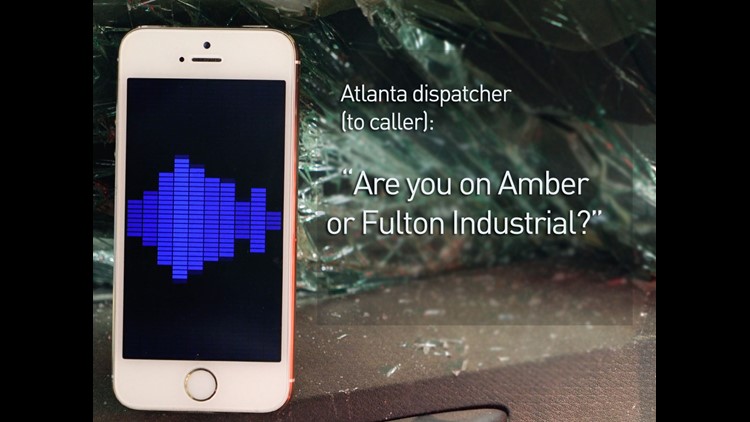

Atlanta dispatcher: Are you on Amber or Fulton Industrial?

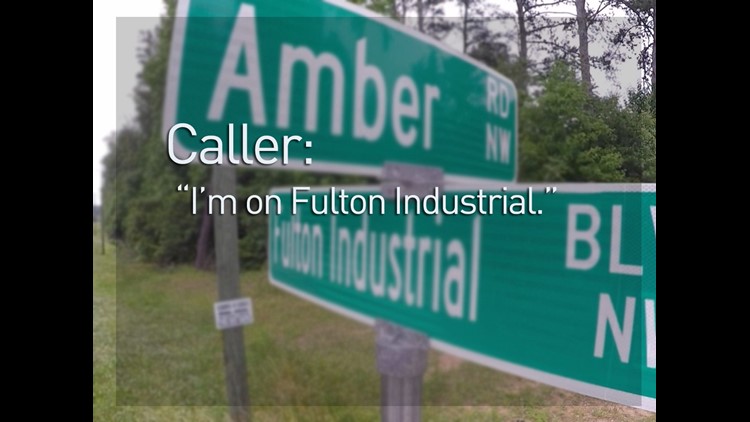

Caller: I’m on Fulton Industrial.

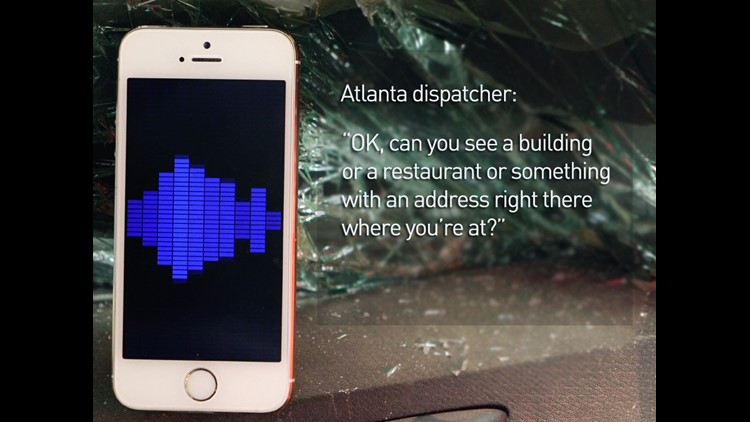

Atlanta dispatcher: OK, can you see a building or a restaurant or something with an address right there where you’re at?

Wes had the exact intersection of the crash, but that wasn’t good enough.

Atlanta Dispatcher: Do they have the physical address?

Caller: There is no physical address. I can get one nearby probably.

“So I pulled into the neighborhood, and gave them an address off the first mailbox I saw,” Price said.

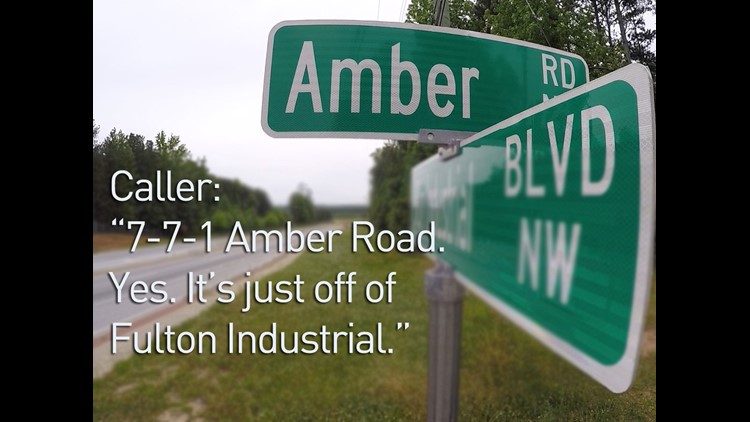

Caller: 771 Amber Road.

Atlanta dispatcher: 771 Amber Road?

Caller: 7-7-1 Amber Road, yes. It’s just off Fulton Industrial.

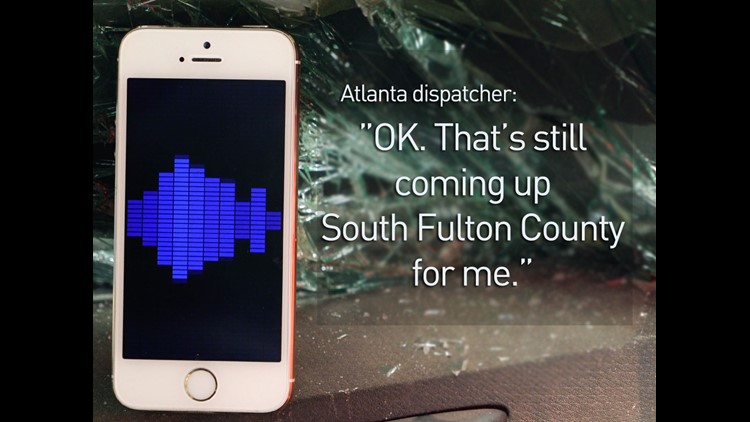

Atlanta dispatcher: OK, that’s still coming up South Fulton County for me.

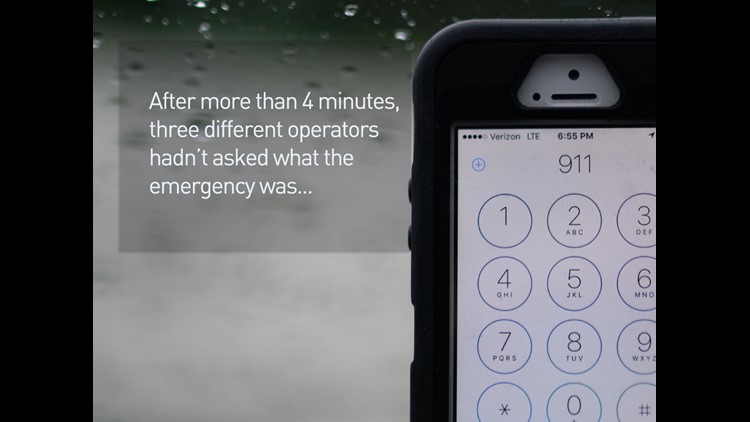

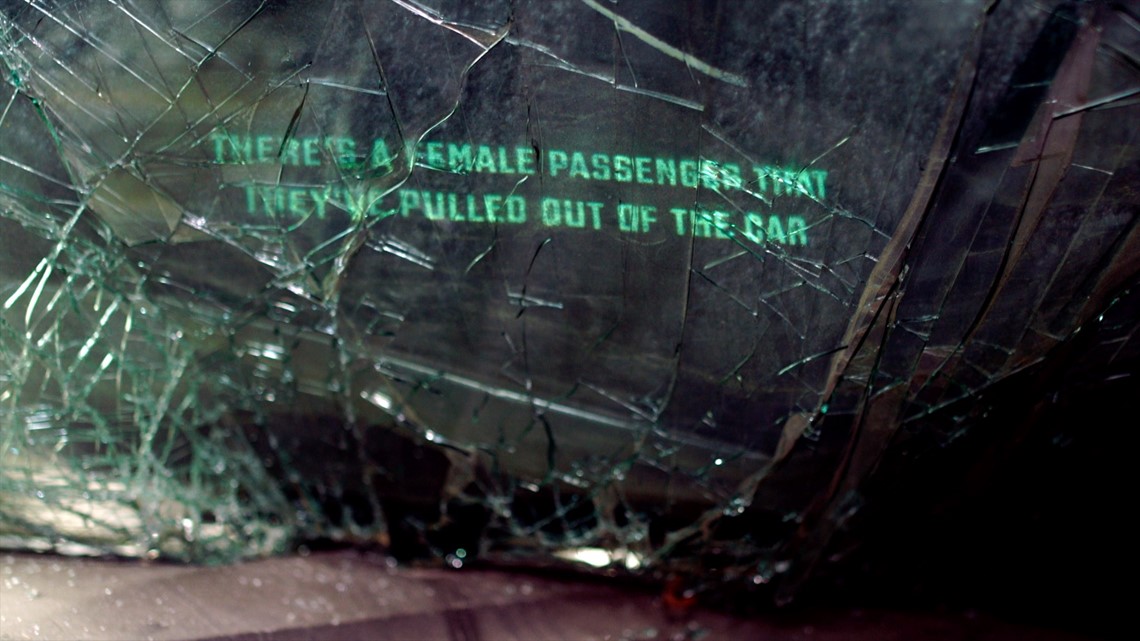

More than four minutes after his first 911 call to Cobb County, three different operators hadn’t asked what the emergency was.

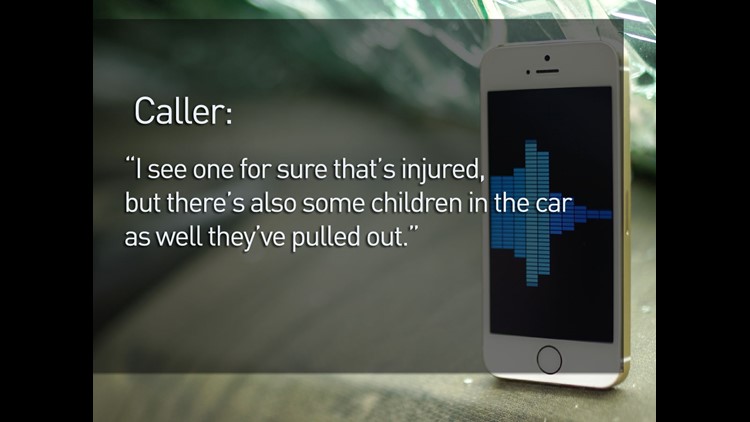

“I don’t think they were all that concerned in responding until I said, ‘Look, there’s an injury out here. They’re pulling a lady out of a car now,’” Price said.

Fulton dispatcher: Atlanta we’re going to respond out, but also if you could respond out as well. If you could check Amber Road and Carol Road, I’m showing that’s near that area as well.

Atlanta dispatcher: OK.

Caller: It is.

Atlanta dispatcher: Carol and Amber still doesn’t come up for me. It says South Fulton.

Caller: They’re arguing back and forth, Fulton County and City of Atlanta. I think Fulton County’s coming out.

Fulton dispatcher: We’re going to respond out, yes sir, we are.

“The time that they spent going back and forth about who was going to cover the emergency I thought was valuable time – critical time – could have mattered whether someone lived or died,” Price said.

Atlanta dispatcher: Attention Engine 38, respond to Fulton Industrial Boulevard and Amber Road NW…on an auto accident with injuries. 17-50 hours.

Atlanta Fire was dispatched four minutes into the third call.

Fulton dispatcher: Atlanta?

Atlanta dispatcher: We have, um, fire and, um, police en route. We had to force something through for them to go to that area.”

While callers may know where they're calling from, their actual location has nothing to do with which 911 center gets the call. It's always the cell tower's address. That's why dispatchers often have a distorted view of callers' locations, and why emergency calls routinely go to the wrong city or county.

“If you start out in the wrong jurisdiction from where you actually are, that dispatcher has to figure out where you are, and then route it to who they think is correct,” said Fred White.

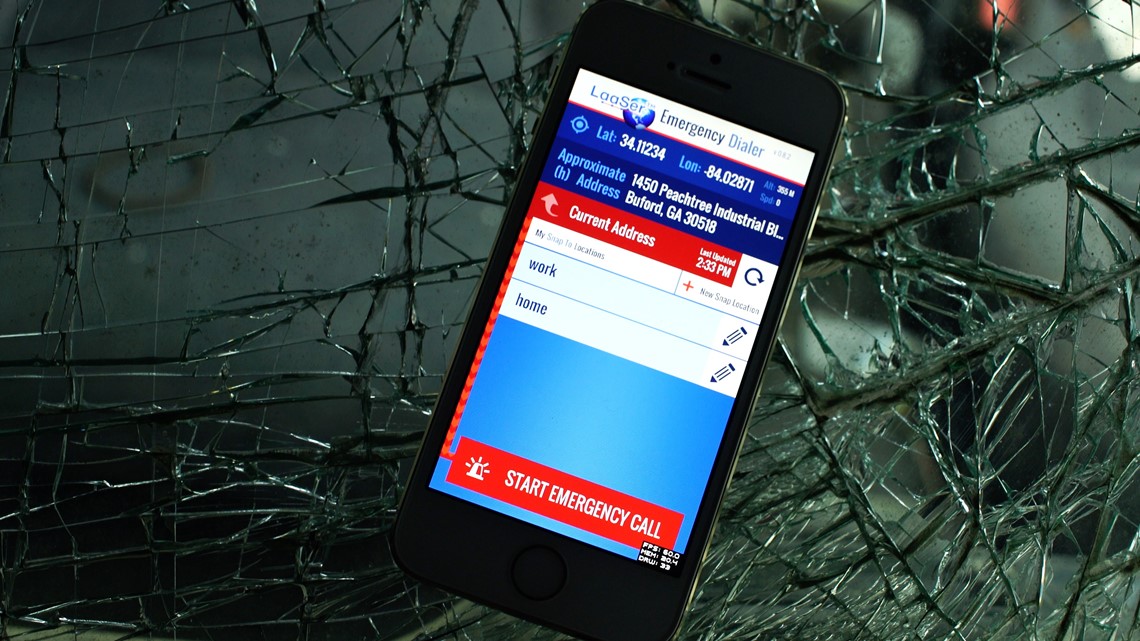

White is the co-inventor of of LaaSer, a patent-pending technology the Investigators successfully tested at the scenes of fatal 911 calls from Georgia to Prince’s Paisley Park.

“911 operators are doing the best that they can with the system that they’ve got right now,” said White.

The FCC has put the LaaSer team on the task force trying to fix the routing problem.

The Investigators tested LaaSer at the pond where Shanell Anderson drowned. She was in Cherokee County and her call hit a tower in Fulton County.

LaaSer correctly routed the call, but the current system sent the test calls to the wrong county.

Keefe: Is it fair to say that essentially we’re using 20-year-old technology to call 911?

White: It’s not only fair. It’s just factually true. When you use your cell phone to call 911, you’re going over a system that was designed and has not been fundamentally changed in over 20 years.

The LaaSer team is close to announcing agreements with some cities and phone carriers, but to get it on every phone, they’d have to get universal adoption by all the carriers or a mandate from the FCC requiring it.

Lost on the Line: An 11Alive Investigation