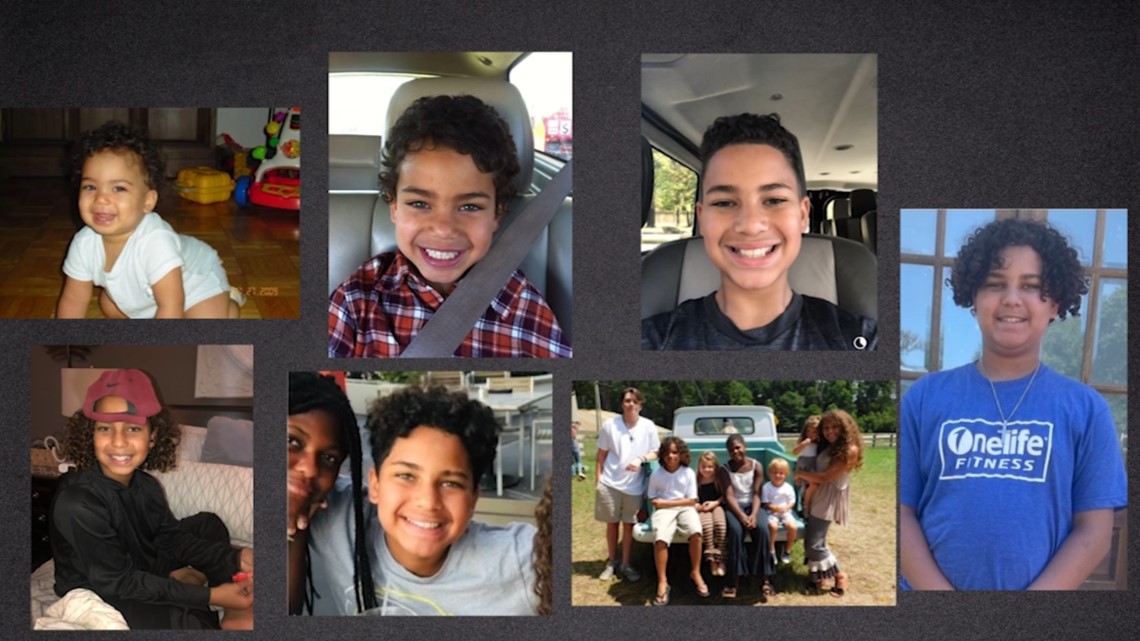

FORSYTH COUNTY, Ga. — You expect the unexpected when you adopt eight kids.

"Loud, active, messy, sticky, stinky," Ray and Lori Carter said describing their family dynamic.

But the Carters said they didn’t expect their son, Trey, to violently attack his mom while riding down the freeway.

“He just lost it and attacked me,” Lori recalled. “He was just livid. 'I can’t be at that school.'”

Trey was born with fetal alcohol syndrome. It impaired his ability to control his emotions and to learn. In second grade, Forsyth County placed him in a special education classroom at Kelly Mill Elementary. It didn’t go well.

“On day one, I think he was restrained,” Lori said.

Physical restraints in the classroom

To calm Trey’s fight or flight tendencies, teachers used physical restraints.

Georgia law requires restraints to be used as a last-ditch effort to keep everyone in the classroom safe and requires staff to try a myriad of other techniques beforehand.

“What we’re trying to do is apply physical touch to get that child to calm down and de-escalate,” explained Jennifer Caracciolo, a spokesperson for the district.

Each time a restraint is used, a report is sent home to parents. The type of restraints include names like "embrace" and "dual-staff horizontal containment." Google the terms and very few images come up to explain what those terms mean.

According to school reports provided by Trey’s parents, staff restrained Trey 20 times in his first month. Trey ended up at Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta depressed and anxious. He was then sent to Laurel Heights to try to sort out why he was threatening harm to himself or the teacher.

But as soon as he returned to the classroom, the restraints started again. Each only lasted a few minutes. The reports outline the danger: pushing, punching, or climbing the door, hoping to leave the room.

Trey’s mom said she believes he couldn’t do the schoolwork and lacked the maturity to deal with his frustration.

“Try harder is something Trey can’t hear because he’s been told to try harder and that just jacks up his anxiety," she said. "If you’re in a wheelchair would you tell someone to try harder to walk? Trey has a brain injury. He has an invisible disability. And it needed to be accommodated."

Are restraints effective?

Teachers must keep classrooms safe for everyone including both the students and the teachers. The reports do indicate times when Trey began throwing chairs and threatening others, posing what staff felt to be an imminent danger.

These incidents almost always occurred in the morning, but the reports don’t say what triggered the aggression.

“I get it, sometimes we miss the cues. But that’s an awful lot of cues to miss,” Dr. Daniel Crimmins said when asked about this kind of repeated use of physical restraints.

Dr. Crimmins is an emeritus professor at Georgia State University and a clinical psychologist who helped train schools on ways to avoid restraints for more than a decade.

He said restraints aren’t generally harmful, but they don’t help either as they burn up time and resources.

“How do we switch that equation from them being invested to reacting to the problem, to preventing the problem and teach the skills that might help this kid with a problem?” Crimmins asked, explaining the purpose of his training.

According to the Office of Civil Rights, Forsyth County Schools used restraints at least three times more than any of the four larger metro school districts in 2017. This was when Trey attended class in-person.

For perspective, Forsyth used restraints more than 941 times last school year. After that, the district with the highest use was Paulding County. It used restraints 308 times.

Crimmins said the other counties aren’t being honest in their reporting or Forsyth has a distinct culture for how it handles students with special needs.

“If I’m being restrained, the message is that I’m truly being disapproved of," he said. "If it’s happening that often, that’s a pretty heavy burden of disapproval to be carrying around.”

Crimmins said studies found restraints are not effective at changing behavior and provide no therapeutic value. Instead, they can escalate negative behavior patterns. Too often, he said the relationship between the student and teacher becomes a power struggle.

Finding a different approach

Caracciolo said since the use of restraints spiked in 2017, there has been a philosophical shift.

“We’re very data-driven. We have conversations about: Why is this data happening? Do we need to provide more training?” she explained.

It’s those conversations that led to teacher training on the Mindset Model, which helps build trust between adults and students that can help de-escalate a situation. More than half of the district’s schools also now use PBIS, a program to focus on supporting positive behavior.

“It’s also tracking student’s behaviors to see if there’s triggers,” Caracciolo said.

In the past five years, Forsyth added 18 percent more special education students, from 5,691 in 2017 to 6,933 this school year. Its use of restraint increased by five percent.

Caracciolo said it’s a sign parents believe the district is doing things right. Sometimes, that still means physical restraint. But she said the district will not use physical restraints if the parent does not approve.

“We’ve obviously evolved it over the years to make sure we’re providing the best support for the students and their families, but it’s a practice that has worked for us,” she said.

It’s not a practice that worked for Trey.

Restraints didn’t cause his problems, but his parents said they have made it almost impossible to get him back into a traditional classroom. Lori let 11Alive News Investigates listen in on a team meeting before Trey left the residential treatment program stemming from that attack in the car.

“He did have some fear about returning back to that school and I talked with him a little bit about the restraints that happened,” the therapist said on the call.

Restraints are still a fear for Trey five years later. Trey never went back to Kelly Mill after second grade because his parents said the district wouldn’t let him change schools. So instead, he bounced between private schools, home-based classes and psychiatric hospitals.

“I don’t know what 20-something restraints the first few weeks of school and going inpatient does to a kid that’s 7, 8 years old with a lower IQ and fetal alcohol syndrome that already had trauma history. I don’t know,” Lori said, frustrated that her son is old enough for 8th grade, but can still barely read.