ATLANTA (WXIA) – Georgia State Senator Renee Unterman (R – 45th District, Sugar Hill/Buford) is chair of the Senate Health & Human Services Committee. She is also an executive with a health insurer that has a billion dollar a year state Medicaid contract, according to state financial records.

The 11Alive Investigators discovered the senator's dual role while attempting to examine the state's most expensive agreements with for-profit companies. The state of Georgia adopted a managed care program for Medicaid in 2005, the same year Sen. Unterman took a job with one of the winning bidders, Amerigroup.

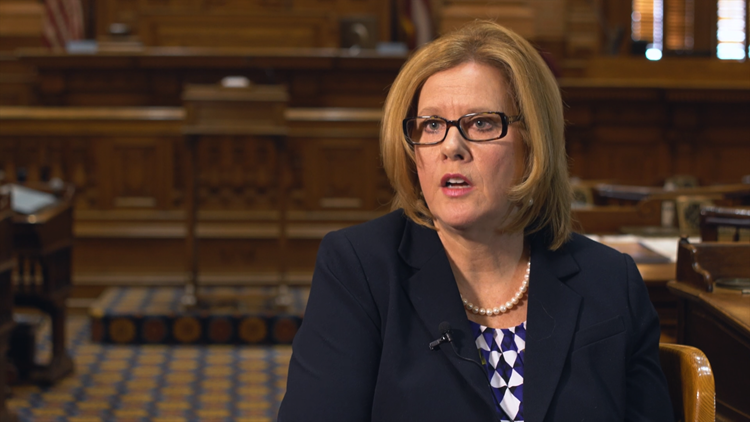

"When I went to work for Amerigroup, they already had the contract," Unterman told 11Alive's chief investigative reporter Brendan Keefe during an interview in the Senate Chamber in late January. "I started working at Amerigroup in 2009."

Unterman's financial disclosures back to 2005, the latest year for which there are accessible records, show she listed herself as a corporate executive with Amerigroup in that year.

"It wasn't 2009, I'm sorry, I got the date wrong," the senator said. "It was 10 years ago."

The chair of the Senate Health & Human Service Committee said she began working for Amerigroup in 2006, which the company confirmed in written answers to our questions. When asked for a firm date of her employment with the state vendor, Sen. Unterman wrote she started working for Amerigroup in September 2005.

State records show Amerigroup became a Georgia Medicaid contractor in July 2005 – which means Unterman went to work for the company two months after it took on one of the state's biggest vendor agreements.

Amerigroup Georgia was paid $1.1 billion last year by Georgia's Department of Community Health, according to state finance records. Those records show Amerigroup is the third-highest paid state vendor. The largest is Blue Cross-Blue Shield of Georgia, also owned by Amerigroup's parent company, Anthem. The company recently received a significant contract for state health insurance.

Unterman's current financial disclosure lists her employer as Anthem – which Georgia paid a total of more than $3.4 billion in tax money in 2015, according to state records showing payments to Anthem subsidiaries Blue Cross-Blue Shield and Amerigroup.

The senator's official biography did not list her decade of employment with one of the state's largest vendors until after the 11Alive Investigators asked why it was missing.

Unterman responded, "My role with Amerigroup is reflected in state disclosure reports."

We downloaded the original state biography in December, and checked the online link frequently after our interview with the senator in late January. It had not changed until late February, when the following line was added: "She currently works on national health care policy for Amerigroup Georgia."

The recently updated biography, however, is still dated August 2013.

We sent a list of questions about Renee Unterman to her employer. Amerigroup did not respond directly. The answers were sent to the State Senate Press Office Director, Jennifer Yarber. Yarber emailed us Amerigroup's answers, which she said, "Anthem asked me to pass along after the interview."

Much of our 18-minute interview with the senator was consumed by trying to get answers to the same questions.

Near the end of the interview, which took place on a day in late January when the Senate was not in session, Unterman's aides interrupted no less than three times, and appeared to become even more agitated as the session continued -- which can be seen in the following video sequence:

The Georgia General Assembly is a part-time legislature. Senators are paid a little more than $17,000 a year, plus a per-diem for each day the Senate is in session. Most lawmakers have full-time jobs outside the legislature, and House and Senate committees are generally populated by elected officials with professional experience in those subjects. For example, some farmers elected to the General Assembly are on the Agriculture committees.

Sen. Unterman is a former nurse, and chairs the Senate Health & Human Services Committee.

"People that serve on my committee are doctors, an anesthetist, dentist; and we all have an interest in health care," Unterman said. "And that's very important when we're transitioning the infrastructure. We've been in a crisis."

The difference is the company Unterman works for has one primary customer: the State of Georgia. The health committee chairperson is not just an employee of a health insurer, she is the Director of Health Policy for Amerigroup Georgia – a billion dollar a year state vendor.

So, Renee Unterman develops policy for the State of Georgia, and she directs a state Medicaid insurer on health policy.

Senators are considered state employees and are bound by ethics rules. Sen. Unterman insists she has not violated any ethics rules, stating, "In no way, have I ever crossed the line on any type of code of ethics, or made any kinds of violation."

We could not find any examples that would contradict that statement.

Unterman literally wrote some of the ethics rules herself. The year she was hired by one of the state's top vendors, she was chair of the Senate Ethics Committee.

Current ethics rules prohibit lobbyist gifts or meals worth more than $75 per day. We found filings where lobbyists from Amerigroup reported paying for Sen. Unterman's meals, but ethics rules do not require the senator or Amerigroup to report the annual salary the state vendor pays her.

Sen. Unterman says there is no conflict because Georgia's Department of Community Health, not the legislature, awards the contracts.

"I'm part of the legislative branch, and what I do is I write laws and develop policy," Unterman said. "And that's part of the executive branch (the Department of Community Health), and I don't have anything to do with that."

The Department of Community Health oversees the contracts and the state's Department of Administrative Services selects the winning bidders, with input from DCH.

An Open Records request from 11Alive News for emails between the senator and DCH shows she is in regular contact with the department that oversees her employer, usually on matters involving questions from her constituents.

"The Department of Community Health is a state agency," Unterman wrote in response to our questions. "And its offices can be contacted by anyone seeking information about the programs it oversees."

The emails show DCH assigns several staff members to answer any question from the senator, a level of direct access we were unable to find for employees of other vendors who contact the agency.

DCH emails obtained through an open records request show the agency provided Sen. Unterman with talking points and other materials to answer concerns from state employees and retirees after the selection of Anthem/Blue Cross-Blue Shield as the state's primary health insurer, which could have put Unterman in the position of advocating for the selection of the company that signs her paycheck.

We are not able to see how the senator responded to such concerns because the Georgia General Assembly exempted itself from its own Open Records Law. We can review lawmakers emails only when they are received by other agencies that are included in the Open Records Act.

A request for the senator's emails from the Department of Human Services was lost for a week in a junk email folder according to the first response from the agency.

Multiple competing bidders recently appealed the state's decision to award the Medicaid contracts to Amerigroup and three other companies. Those appeals were filed by lawyers for bidders accusing the state of violating its own bidding rules by changing the evaluation team in the middle of the process.

About half of the evaluators were dismissed, and others were added after the evaluation process had already begun.

We found no evidence of any involvement on the part of Sen. Unterman in the bidding process that resulted in her employer keeping its existing contract and winning a second, exclusive contract.

We wanted to see if a decade of managed care had improved the health of Georgia Medicaid recipients, and if the program had saved Georgia taxpayers money.

There were several benchmarks set for health outcomes, but all three contractors have missed some of them. All three contractors have missed the target for reducing the percentage of low birth weight babies in Georgia, a figure that remains stubbornly above nine percent.

One person directly affected by the Medicaid HMO web in Georgia was speech pathologist Ellen Roberts. But not in the way you might think.

Roberts, who has dedicated her life to helping children with special needs, spoke out when the state was deciding to make children under the care of Medicaid go through HMOs to get treatment.

"They, by all means, are private companies, and their job is to make a profit," Roberts said. "And looking at monies that come down from Medicaid, the only way you can make a profit, is to limit the number of in-network providers, and also to deny services."

Roberts criticized Georgia's Medicaid HMO program on national television. But while she was writing dozens of letters to state elected officials, someone else was writing letters of their own to the state – anonymously accusing the therapist of felony Medicaid fraud.

"You think this was payback?" 11Alive's Brendan Keefe asked her.

"Oh yes, definitely payback," she replied.

She took on a multi-billion dollar industry, and it nearly cost Ellen Roberts everything. She was indicted and arrested for conspiracy to commit Medicaid fraud.

Roberts spent five years and all of her savings defending herself. Then, just 10 days before her case went to trial, state prosecutors mysteriously dropped all charges, admitting they did not have a case.

"And you never did find out who was accusing you?" Keefe asked.

"No," Roberts said. "It was based on two unsigned letters."

"In your mind, they tried to shut you up?"

"Yes," she said.

"And even at all of this cost, it didn't work?" Keefe asked.

"No. And they're probably – when they see this, they will probably try something else," she said. "I don't put it past them."

Roberts initially thought she could find answers with the Department of Community Health. But they would not share information about the state's Medicaid HMO process with her.

Determining the value taxpayers are receiving from their Medicaid HMOs is more difficult. Medicaid costs are soaring for several reasons, so only empirical analysis would be on comparing the cost per Medicaid recipient before and after managed care.

We were unable to crunch those numbers because the state will not let us – or you – see them.

When the 11Alive Investigators first asked for copies of the Medicaid contracts under the Georgia Open Records Act, DCH replied that the agreements were exempt from disclosure because they contain "trade secrets." We appealed on the grounds that people paying for the state's most expensive contracts should be able to see what they are getting for their money.

DCH responded with a flash drive containing three folders, labeled Amerigroup, Peach State and Wellcare.

The Peach State and Wellcare folders included the Medicaid contracts, but with key sections redacted. Pages detailing the "Capitation rates" – how much the state pays each Medicaid recipient – were entirely blacked out.

One folder was completely empty – the Amerigroup folder.

A DCH spokesperson told the 11Alive Investigators it was a mistake, and purely a coincidence that the only contract missing from the Open Records response was the one from the company where Sen. Unterman makes a living.

The agency gave us the Amerigroup contract a few days later, and it, too, contained blacked out pages where we would otherwise be able to tell how much money each Medicaid recipient costs the taxpayer. The exception cited by DCH was, once again, "trade secrets."

Now, more recently, Amerigroup has been awarded a new contract, granting them an exclusive right to be the HMO for all of Georgia's foster kids.

11Alive News asked the company several questions, but the only written answers from Amerigroup were the ones delivered to us by the State Senate's press office after our interview with Sen. Unterman.