FORSYTH COUNTY, Ga. — A marker on the Cumming courthouse square will soon remind residents of a lynching that changed the face of Forsyth County forever.

Shortly after the lynching of a Black man named Rob Edwards in 1912, more than a thousand Black residents were forced out of the county.

Forsyth County remained nearly all-white for most of the 20th century. Today, only four percent of the county's population is Black.

“All of the negro people had to leave,” said Elon Osby, a descendant of Black landowners in the county. “There was knocking on the door and they were told to get out."

Osby’s mother, Willie Mae Bagley, was just two years old when the family was forced to flee their home. Tax records show Osby’s grandparents, William and Ida Bagley, owned 60 acres.

► WATCH | 'Equality Matters' special Wednesday at 9 p.m. on 11Alive

There was little time to arrange a sale, with Black churches set aflame, and night riders terrorizing Black sharecroppers and landowners, according to contemporary newspaper accounts.

“Enraged White People Are Driving Blacks From County,” declared the headline in the October 13, 1912 edition of The Atlanta Constitution. The article went on to say that, “recent outrages committed against White women in the county have so enraged the White people that many of them have determined to drive the negroes, good, bad, and indifferent, from the county.”

The racial cleansing started in 1912 but made national news in 1987 when activists marched into Cumming to bring awareness of the county's racist history. They were met by white residents with "Keep Forsyth White" signs, chanting the N-word, and throwing rocks.

Showing that the racist history was not in the past.

The lynching of Rob Edwards

Rob Edwards was arrested in September of 1912 along with other Black suspects accused of raping and murdering a young white woman named Mae Crow.

Crow was found unconscious in the woods near Browns Bridge. Despite reports to the contrary, the young woman never regained consciousness or identified her attackers. The suspects arrested were literally the closest Blacks to the crime scene. One of them reportedly confessed to the crime and implicated the others.

Patrick Phillips documented in his book, Blood at the Root, that the confession by Ernest Knox was coerced by a prominent Cumming resident who mock-lynched the 16-year-old boy with a rope from a nearby well.

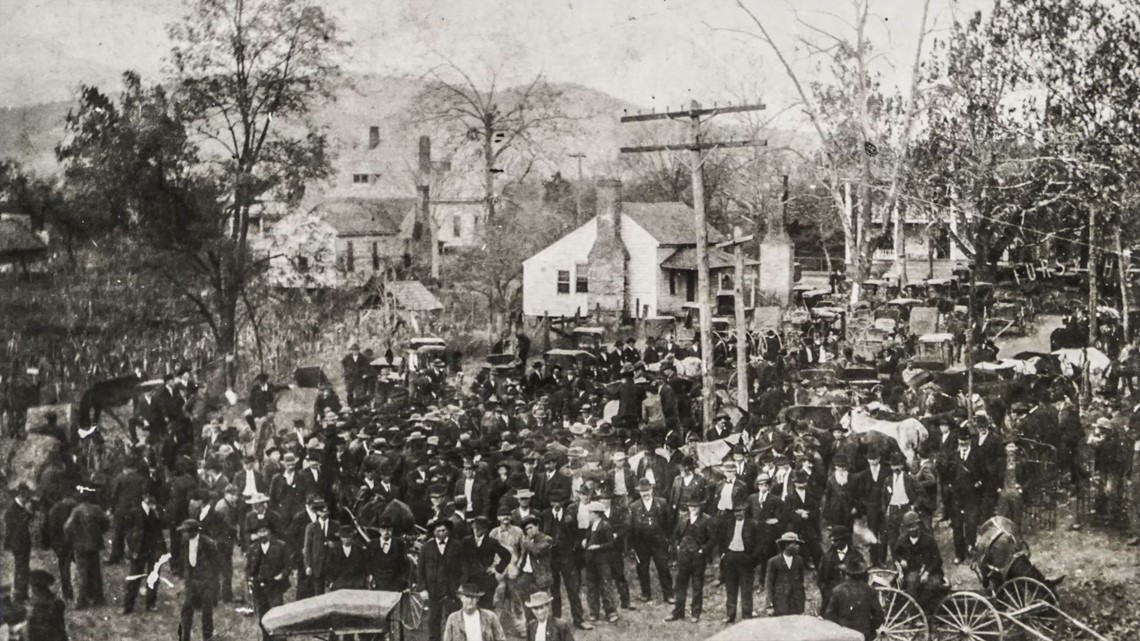

The suspects were taken to the Forsyth County Jail. Outside, on the Cumming Square, a lynch mob of hundreds of residents soon formed.

The sheriff at the time, Bill Reid, went home and left a single deputy — his rival in multiple elections — to guard the prisoners. Deputy Lummus held back the attackers as long as he could before they were able to storm the cell holding Rob Edwards.

“The lynching of Rob Edwards,” recounts Phillips, “involved a very large crowd gathering outside of the jail, dragging him out of the jail, beating him with crowbars, dragging his body around town behind a wagon, and then eventually his corpse is hoisted on a telegraph pole and everyone in the crowd take turns shooting into his body.”

Not a single person was held accountable for the lynching, despite thousands of witnesses.

It was not the only lynch mob to form in downtown Cumming that week. Another young woman, Ellen Grice, accused two Black men of attempting to rape her inside her bedroom in Big Creek. The national guard had to rescue the suspects in that case from the Forsyth County Jail after the mob viciously beat a Black pastor for questioning the woman’s reputation.

Unfounded rumors that Black residents were planning to dynamite the town created hysteria among the white population in the days before Mae Crow was found beaten and unconscious near what is now Lake Lanier.

Two more hangings

Earnest Knox and Oscar Daniel, both teenagers, were convicted in two separate trials on a single day.

The jury was all white.

Knox’s alleged confession was bolstered by the testimony of Daniel’s sister, who was visited the night before by the prosecutor and the judge, according to Phillips’ research.

Jane Daniel was also the wife of Rob Edwards and gave her testimony after seeing her husband lynched just outside the same courthouse where she would avoid the noose.

The judge who presided over the case, Newt Morris, would later participate in the 1915 lynching of Leo Frank in Atlanta.

Public executions had been outlawed by 1912, so the judge ordered that a blind be built to block the public from viewing the hanging of Earnest Knox and Oscar Daniel.

The night before the execution, someone burned down the blind.

The executions took place on a hill off Kelly Mill Road and Tolbert Road in what was described by newspaper reporters as a natural amphitheater.

“Five thousand people in a county of ten thousand came to celebrate this,” Phillips said.

In the lower-right corner of the only surviving photo of the scene immediately after the executions, you can see a handful of Black men near a wagon.

That’s one of the last photos of Black faces in Forsyth County between 1912 and 1987.

The only Black residents were the dead

The 1910 census shows there were 1,098 Black or mixed-race residents living in Forsyth County. By the 1920 census, that number was reduced to a handful of Blacks working for a white farmer near the border with what is now Fulton County.

“There are these long stretches where, decade after decade, the Black population of Forsyth County is zero,” Phillips said.

The author documented incidents over those decades where Blacks who crossed the county line were arrested, run out of town, or shot. Even Black servants of wealthy white visitors were forced to leave in the early 20th century according to newspaper reports.

A Black Atlanta firefighter was shot in the head near Lake Lanier in 1980 purely for the color of his skin. Locals heralded the assault convictions of two white men by a Forsyth County jury as a sign the county didn’t deserve its racist reputation.

Jim-Crow-era Forsyth County didn’t have the familiar ‘whites only’ and ‘colored’ signs on bathrooms, water fountains, and lunch counters that were hallmarks of segregation.

That’s because there was no Black population to be segregated.

For some 75 years, the only Blacks in Forsyth County were buried in the many graveyards next to burned-out or abandoned Black churches.

One such graveyard was recently unearthed. About eight complete headstones are visible at the old Stoney Point Baptist Church location, wedged now between rows of upscale homes in two wealthy subdivisions.

Black cemetery hidden in Forsyth subdivision is example of county's racist history

Dates on the tombstones of forgotten Black men, women, and children all stop before 1912.

Family members would not have been able to visit the graves of their ancestors without the threat of getting lynched or shot. So the graves sat alone well into the 21st century.

The Cumming/Forsyth County Historical Society has joined with volunteers to clean up the graveyard. Some of the volunteers are descendants of the white families who founded Forsyth County.

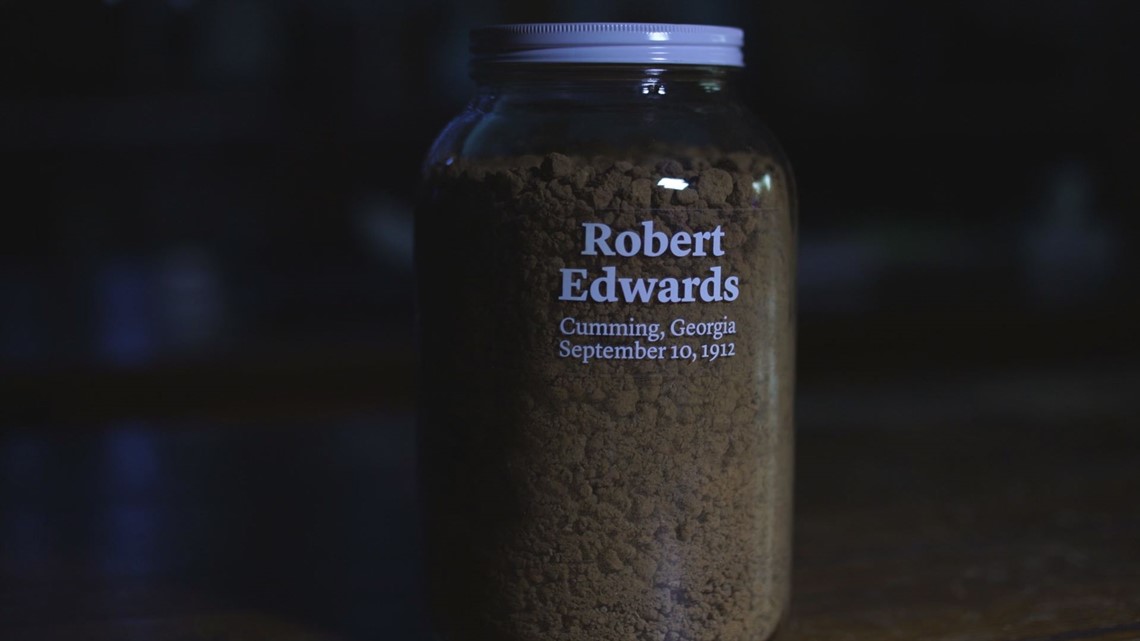

The historical society joined forces with the Community Remembrance Project and the Equal Justice Initiative to collect soil from the spot where Rob Edwards was lynched. The jar will join hundreds of others representing lynching victims at the Equal Justice Initiative memorial in Montgomery, Alabama.

The Community Remembrance Project of Forsyth County is also the group behind the push for the marker on Cumming Square, which was approved unanimously by local leaders.

What happened to the Black-owned land?

Multiple authors have researched the properties of Black landowners with varying results.

One local author claimed many Black landowners were able to sell, sometimes at a profit.

“Some people sold, and got out early,” Patrick Phillips agreed. “But any white American who is thinking that lets Forsyth County off the hook should imagine someone coming into their house with an attorney and a briefcase and paperwork and a check who says, ‘I’m going to give you this for your house. You can take it or I can shoot you, or I can drag you around town with a noose around your neck, or burn your house to the ground.’ The seller who accepts that term has not been compensated fairly.”

Journalist Elliot Jaspin documented several Black landowners who sold at a loss or not at all.

In his book Buried in Bitter Waters, Jaspin writes that 24 Black landowners and seven churches were able to sell.

“The worst case was Alex Hunter, who, just three months before the expulsion, bought a farm for $1,500. Faced with death or leaving, he sold it in December 1912 for $550,” Jaspin wrote.

Jaspin insisted there is no record of sales for 34 Black-owned properties, including the two lots owned by William and Ida Bagley.

Elon Osby put is this way: “When you were forced to leave, and you’re fearful of your life, would you have come back a couple of months later so you could do a business transaction and sell this property?”

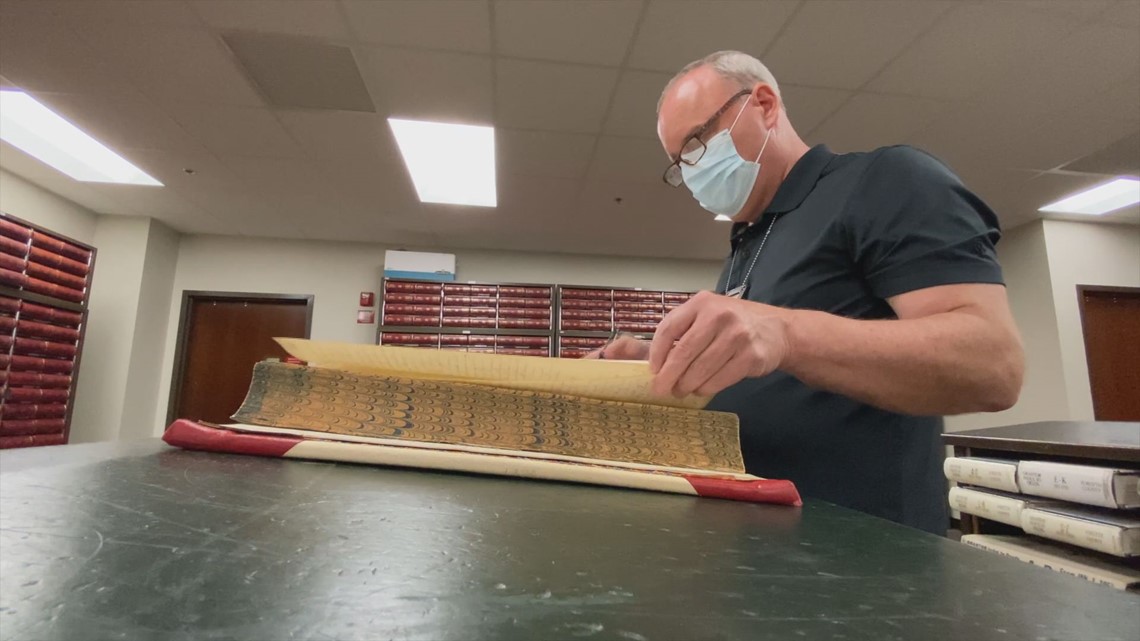

11Alive's investigative team, The Reveal, spent several hours in the Forsyth County Clerk of Superior Court real estate records room over three separate days researching only the Bagley property. Clerks and a professional title researcher generously offered their assistance to us and seemed genuinely interested in the final results.

We were unable to find an original deed for the Bagley land, but we do know the specific lots they owned because tax records show the militia district taxed William and Ida Bagley for 60 acres in 1912.

The Bagley property spanned two land lots, and we traced one through a dozen transfers all the way back to 1919. That’s where the trail stops because we couldn’t find an earlier deed transfer into that seller’s name.

Research on the second land lot took us back to 1923, where the deed book references a much earlier sale in 1877. When we went looking for that sale, we couldn’t find any record of it after an extensive search through handwritten records in a 150-year-old deed book.

What’s notable is that a series of transfers in the 1920s and 1930s all add references to that 1877 sale that had nothing to do with the 20th-century transactions. Looking through hundreds of other routine deed records in those books, we didn’t see any others that so conspicuously noted earlier, unrelated transactions.

Also, the seller referenced in the supposed 1877 sale was a large landowner and prolific seller of lots in the late 19th century. It would be a good name to choose if you wanted to convince a future title researcher to look no further.

We did find a similar record in 1876 with the identical last names of the referenced seller and buyer from the later documents, but that sale had different first names, and both the lot number and year were both off by one.

That deed is for the next lot over from the Bagley place.

We simply were unable to find a single record for either lot of the Bagley property that would explain how the sellers in 1919 and 1923 obtained them.

A large portion of the old Bagley place is now an upscale subdivision with dozens of homes valued close to half a million dollars each.

The current owners would have no way of knowing that, a dozen or more transactions before, the land had belonged to a Black family forced out in the dead of night.

“I wonder what that land, that my grandfather had, I wonder what it’s worth,” Elon Osby asked.

Newspapers from 1912 vanished

Most issues of the Forsyth County News from the last century were recorded on microfilm and then provided online through the Georgia Newspaper Project.

But not 1912.

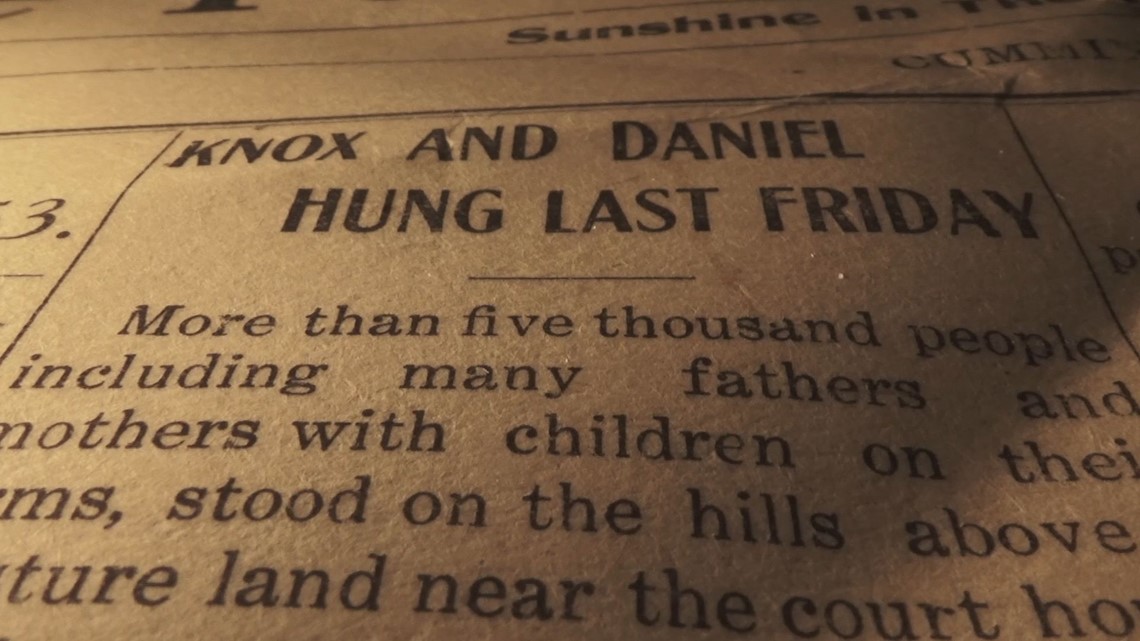

There is only one copy of the Forsyth County News that survives from the entire year of 1912. It’s the Halloween edition that featured an article celebrating the public executions. The laminated front page, preserved in the historical society, boasts the headline, “Knox and Daniel Hung Last Friday.”

The article begins, “more than five thousands people including many fathers and mothers with children on their arms…saw two negroes pay the death penalty for criminal assault and murder. The great crowd cheered as the negroes went through the trap.”

The lone-surviving paper insists that 16-year-old Knox confessed one last time before he was hanged.

We don’t know if the other editions of the paper were never microfilmed, if they were destroyed years ago, or if they’ve disappeared more recently.

What we do know is that someone didn’t want the rest of 1912 — or even 1913 — to be preserved for future judgment. The year 1912 is quite literally the year that shaped Forsyth County for the next century.

The 1987 reckoning

January 1987 brought a blanket of white snow, and buses of Black and White protesters to Cumming.

Civil rights leader Hosea Williams joined local white dissenters in a march for racial justice. They were met with hundreds of angry white residents chanting the N-word, throwing rocks, and carrying signs that read “Keep Forsyth White,” according to footage we found in the 11Alive archives.

Local leaders at the time, and some white residents now, claimed the white supremacists were outside agitators. Records showed seven of the eight people arrested at that first march had addresses in Forsyth County.

Among the marchers for racial justice were local residents Patrick Phillips and his family. He said outside agitators were also blamed for running out the Black population in 1912.

“Not outside agitators,” Phillips said, “but in fact a really endemic fear and bigotry and readiness for violence that was taught one generation to another and passed down.”

The images of residents aggressively defending their all-white county shocked the nation, while the images of busloads of Black activists led Forsyth County to call it an invasion.

Hosea Williams organized a second march that month with thousands more protesters. This time, hate groups from all over the South descended on Forsyth County, while many Cumming residents stayed home. Georgia State Patrol troopers, GBI agents, and deputies from surrounding counties successfully kept the two opposed groups apart.

The nation was watching, and so was Oprah Winfrey

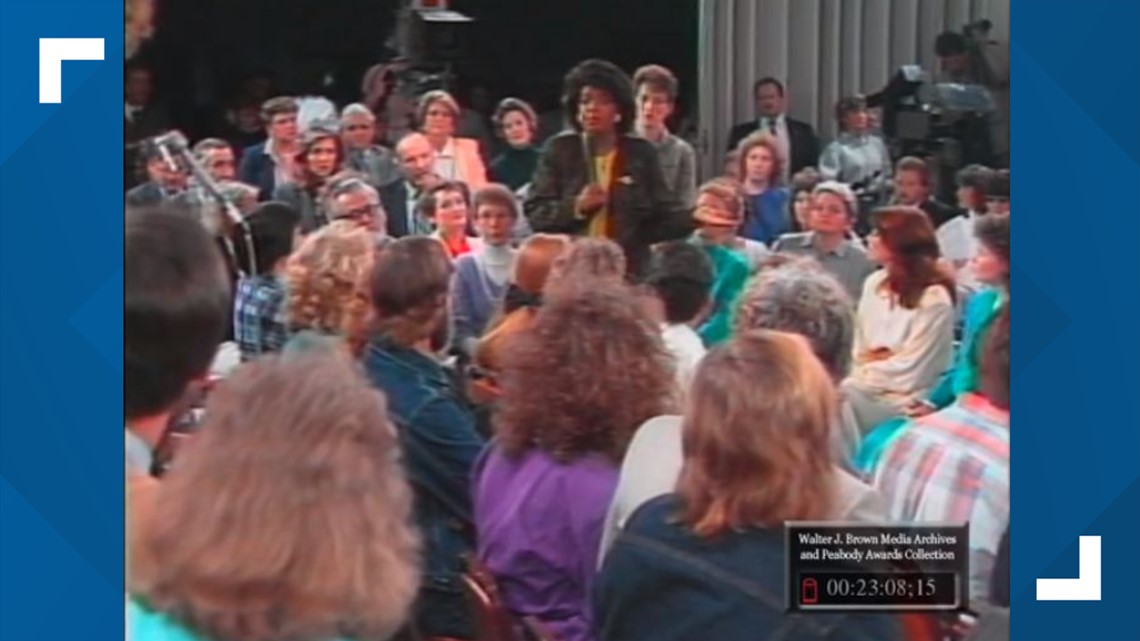

Oprah’s nationally-syndicated talk show was barely a half-year-old when she brought the show to Forsyth County in 1987. Hosea Williams was arrested picketing outside the taping after Oprah chose to include only Forsyth County residents.

Oprah was the only Black person in the crowd, as many residents defended their decision to stay all-white, some casually using the N-word to Oprah’s face.

There were dissenters who said the time had come to have Blacks and whites living together in the county, but the majority of the comments shocked Oprah and her production crew so much that they literally got out of town before sundown.

Forsyth County residents and officials blamed the press for creating an unfair image of their community. We encountered similar responses from some of the old guard when researching this story in 2020, with one older resident asking why this has to be the legacy of Forsyth County.

A bi-racial commission was created in 1987 after the demonstrations and the Oprah show, but it ended with two reports — one Black and one white, with no agreement between the two.

Forsyth would balloon in size starting in the 1990s not because of Black or white, but green.

Money poured into the county with development of property near Lake Lanier, large corporations building office parks and warehouses, and subdivisions sprouting up along the Georgia 400 highway, linking the county to Atlanta.

Now, a bedroom community in metro Atlanta, Forsyth County has held the title as both the wealthiest and fastest-growing county in Georgia in recent years. The largest minority group here is Asian, with an influx of Americans of Indian heritage.

In raw numbers, only four percent of the county's current population is Black, according to last year’s estimated census numbers. That's more Black residents living in Forsyth County now than have lived there in the last hundred years, with six percent fewer Black residents than there were in 1912 before they were run out.

Soon, a historical marker will tell the story of how a Black man was brutally lynched on Cumming Square, so the increasingly-diverse community can begin to heal after nearly a century of exclusion.

“This with the marker is a first step,” Osby said. “I hope that it will continue. I hope that will be other efforts made by white people to make this a new norm for Forsyth County and everywhere else in the world.”

The Reveal is an investigative show exposing inequality, injustice, and ineptitude created by people in power throughout Georgia and across the country.