ATLANTA — More than 1,600 people are sitting in Georgia’s prisons for crimes they did not commit. Or at least that’s what research by groups such as the Innocence Project suggests.

Now, one district attorney says he’s ready to do something about it – reopening cases defendants say – his office got wrong.

Fulton County’s Conviction Integrity Unit (CIU) has only been active for five months, but already, its small staff has received 62 petitions for review. Half of those requests came from defendants who say they are innocent.

Aimee Maxwell was hired to lead the effort. It is now her job to sort fact from fiction. Maxwell has spent most of her career as a criminal defense attorney, most recently serving as executive director of the Georgia Innocence Project.

RELATED: After being sentenced to life behind bars, man gets second chance with job at Tyler Perry Studios

“It is a difficult process. We can’t just look at what someone says, nor can we look at our file and say yes or no this person is innocent or we believe them. We’re going to have to basically re-investigate these cases,” Maxwell explains.

These are serious offenses. According to an open records request, The Reveal learned 23 of the cases involve murder. Twelve of the cases involve armed robberies, four rapes and other serious convictions - including kidnapping and child molestation.

Defense attorneys submitted most of the petitions, but 18 came directly from the accused. Jimmie Gardner is not surprised.

Gardner says he wrote hundreds of letters and legal petitions while serving nearly 27 years in prison, for a crime the courts in West Virginia later ruled, he did not commit.

“I’ve written ACLU, I’ve written organizations, I’ve written NAACP, Action Network. I’ve written lawyers, congressman, senators, I’ve written presidents – plural," said Gardner.

All but one, led to a dead end.

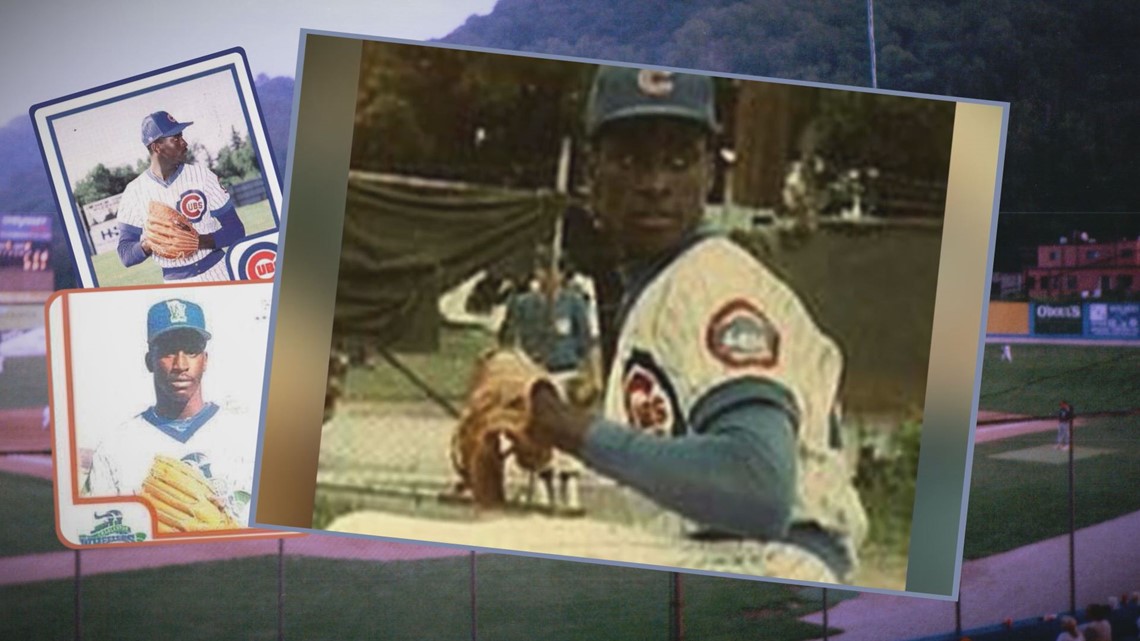

Gardner was born in south Georgia, but spent most of his youth in Florida. He loved sports, especially football, but it was baseball that turned into a career.

Gardner was 20-years-old when police in West Virginia questioned him about two sexual assaults. He was a young, ambitious baseball player in the South Atlantic League, playing for the Charleston Wheelers.

► WATCH | The Reveal Sundays at 6 p.m. on 11Alive

Even though Gardner says he was on the mound pitching during one of the assaults and records indicate none of the victims identified him directly as the attacker, the state’s chief blood analyst testified Gardner’s DNA likely put him at the crime scene.

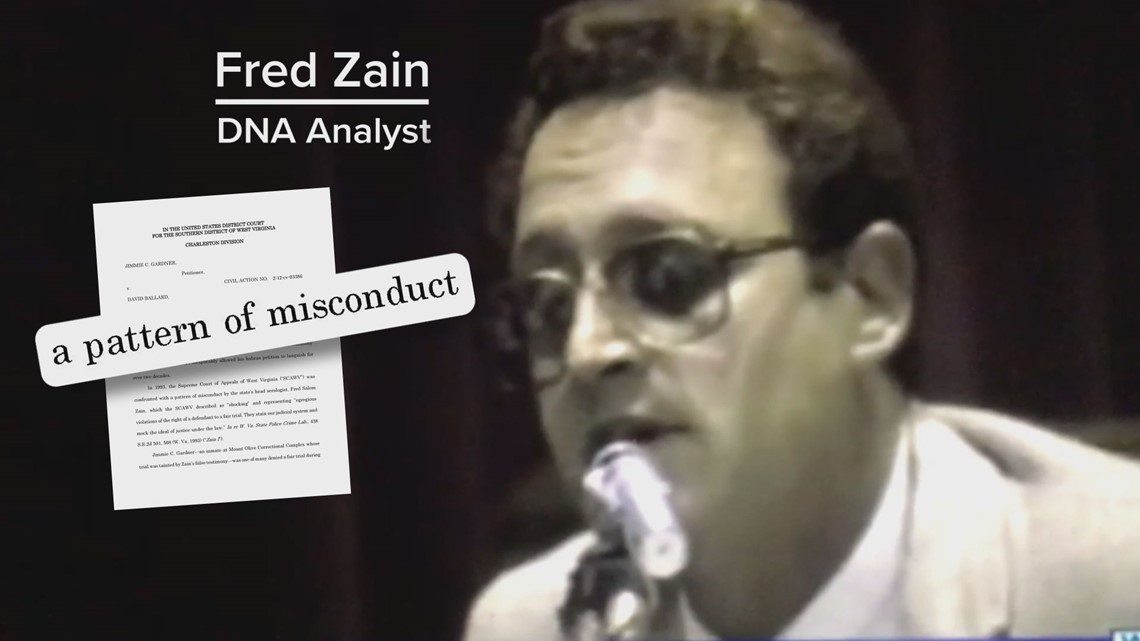

Fred Zain told jurors, Gardner’s DNA and that of the attacker found at the crime scene, were too close a match to rule him out. The state argued the same person committed both crimes, but the jury only found him guilty in one. Still, he was sentenced to up to 110 years to serve.

“In the beginning I had rage. I was totally enraged. I spent the first few years in solitary confinement and I was in isolation for approximately 23 months. During those 23 months I had to soul search. Find out who I am, what I was about,” recalls Gardner.

Three years into his sentence, Zain came under fire for a pattern of falsifying information, calling into question the integrity of his testimony in all his cases.

Gardner filed a writ of habeas corpus in 1993, but was unsuccessful. Nearly a decade later, he filed a similar petition in federal court. It was then, 22 years after his conviction, a federal judge vacated his sentence, comparing his case to ‘legal purgatory.’

Gardner says once he was able to review the actual lab results, which his defense never received before trial, he learned at least one test excluded him as a suspect, since the rapist had a Type A blood. Gardner has Type O.

“I don’t think any human being should spend one second in a jail if that person is not justly convicted,” said Fulton District Attorney Paul Howard, who says it is stories like Gardner’s that prompted him to create Georgia’s first CIU.

The district attorney’s office would not tell us the names of the defendants involved in the cases they are looking into.

“Victims should not have to go through the trauma of knowing that we’re looking at a case unless we’re really going to dig down,” explained Maxwell, who says the process to overturn a conviction will be, “an extraordinary case.”

Maxwell says the petitions received so far aim to raise questions about the integrity of witnesses interviewed, or alibis that were never checked. She says they’ll start with cases that rely heavily on DNA to see if new tests can reveal new information.

The appeals process doesn’t review or retest evidence. It’s hard to prove allegations of bias in how the proceedings were conducted. But those are the kinds of concerns a CIU can review.

Her unit will also look at whether offenders were sentenced too harshly. Twenty eight defendants for crimes such as aggravated assault and voluntary manslaughter have asked for a sentence modification.

“It takes a lot of courage and a lot of integrity for an elected official to look at his own decisions to make sure that justice was done,” said Maxwell, who insists she’s ready to confront Howard with any mistakes she might find.

Since Howard became the DA in 1997, four people have had their convictions overturned according to the National Registry of Exonerations. DNA exonerated one man. Two other defendants won new trials because the courts ruled prosecutors presented inappropriate or false information.

In the last, a double murder case, Howard says his office learned after the trial that their key witness was actually in jail at the time of the crime and couldn’t have seen it.

“When I confronted him, he admitted he had lied,” said Howard.

Howard says he’s counted 36 conviction integrity units across the country. Gardner wants more. He never had a DA like Howard, willing to give his case a second look.

“If the conviction integrity unit was around in 1990 [in West Virginia] I would not have served 27 years. They would have reviewed my case and [seen] that there was false testimony, false evidence. Evidence showed my innocence, not guilt.”

Gardner has now returned to Georgia to rebuild his life. He tells the story from childhood to manhood, recounting each person involved using their full name, almost like the credits at the end of a movie. He wants those who have had a positive - or negative - impact to be fully recognized.

The immaculately dressed 54-year-old sits in his mother’s living room, grateful for her love and support. He is also grateful for her faith.

Gladys Gardner says she spent several days fasting, tucked in her bedroom closet in prayer, asking God to set her son free.

Around the same time, Gardner says he was in the courtyard at Mount Olive Correctional Center, when a beautiful blue butterfly landed on his hand.

“I walked around that compound and had conversations with people and that butterfly stayed on my hand the entire time," remembers Gardner.

He says after two hours, it flew straight over the prison’s barbed wire. In that moment, he knew something had changed. When his mother called to say she believed he would soon be released, Gardner already knew it.

A week later, he stood before the federal judge that would make it official. Gardner remembers thanking the judge for taking the time to review his case.

“He said don’t thank me. I didn’t do anything that shouldn’t have been done 27 years ago. Look, I did what was right," remembers Gardner.

Since his release, Gardner is now using his freedom to advocate for criminal justice reform. He is volunteering with the Georgia Innocence Project and started his own non-profit to help those released from prison. He wants to create a transitional housing environment to make it easier for those re-entering society to access healthcare, especially mental health services, and to give families a safe place to reconnect.

More of The Reveal:

The Reveal is an investigative show exposing inequality, injustice, and ineptitude created by people in power throughout Georgia and across the country. It airs Sunday nights at 6 on 11Alive.