STATESBORO, Ga. — In child welfare, it's supposed to be the state that helps abused and neglected children, but hundreds are abandoned to state custody each year simply because their parents don’t know what else to do.

Its been called "trading custody for care" and even a "passport to services." April Bonaccorsi calls it disgusting.

“Because if you don’t have a lot of people who inform you on your rights, you question what’s really available for your child," Bonaccorsi said.

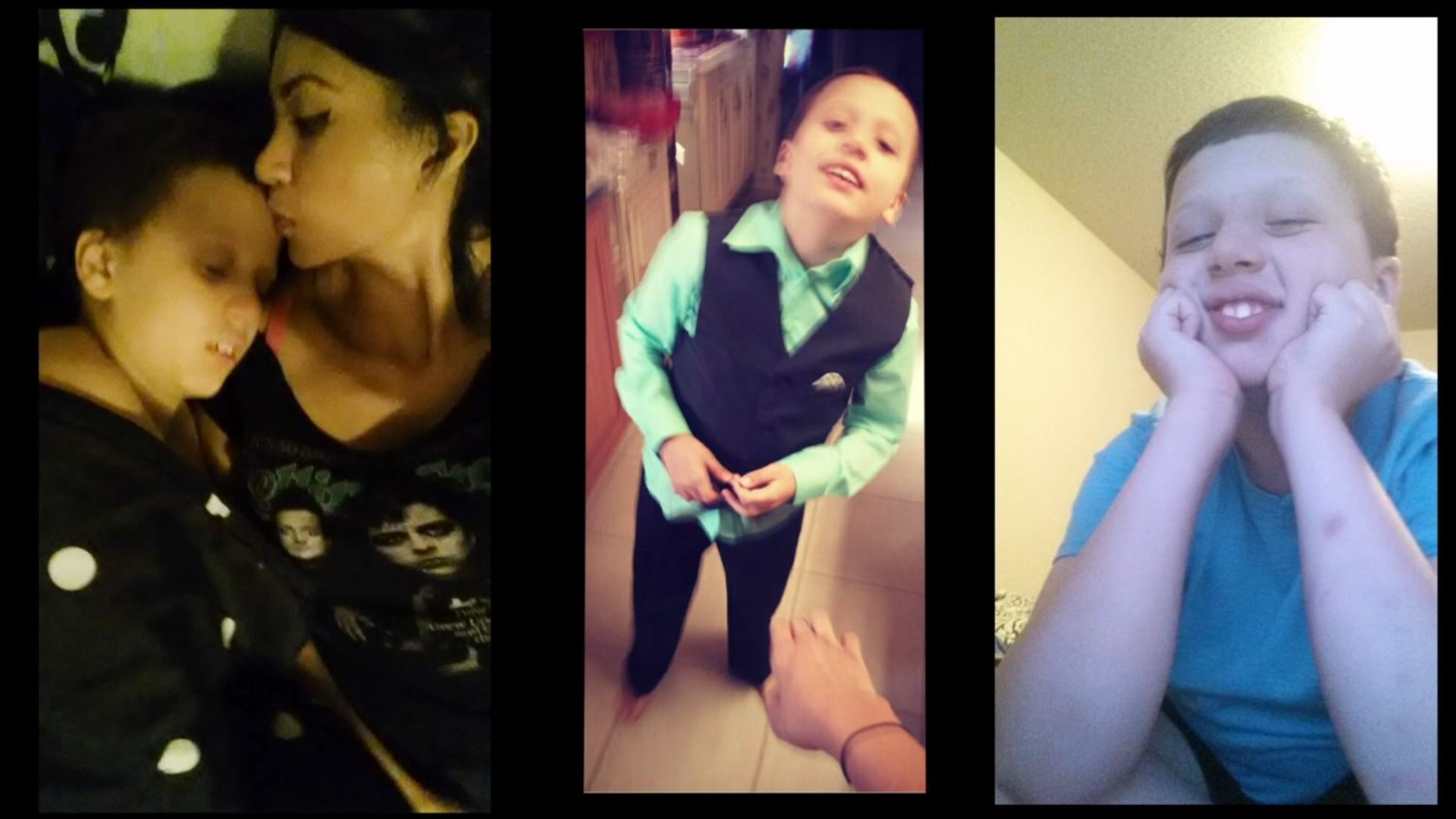

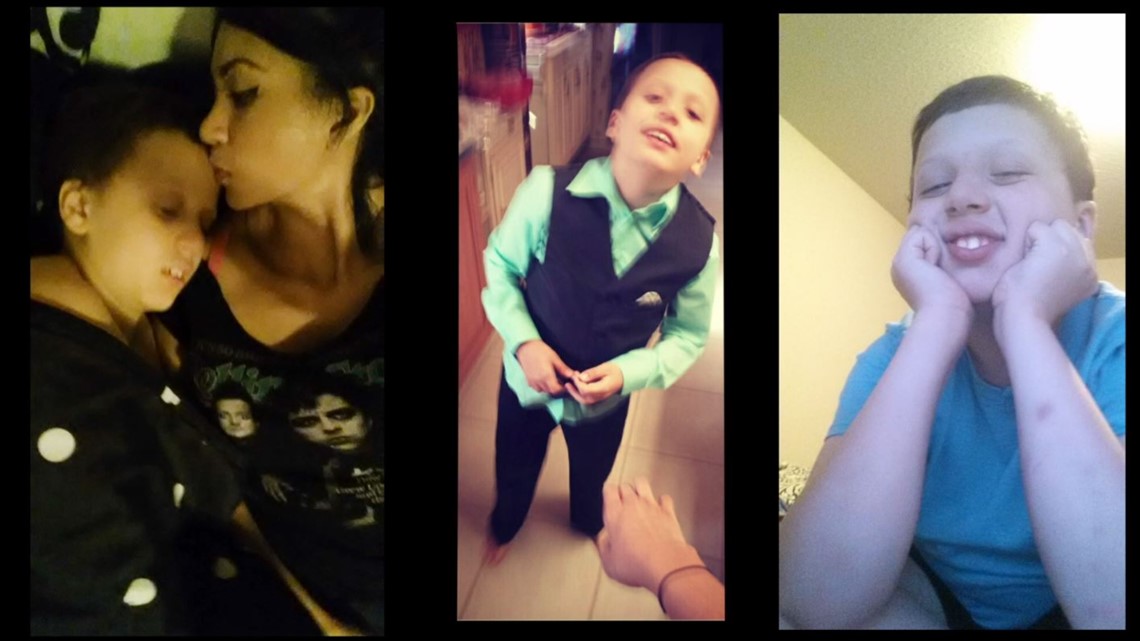

She has three children. Ava is the newest member, just three months old, she demands a lot of her mother’s attention. Three-year-old Aiden seems willing to oblige, as long as he gets to lend a hand. And then there’s 14-year-old Bradley.

“He’s always in my heart. We talk about him everyday. Everything I do I think about Bradley,” Bonaccorsi said, with a mix of emotions on her face.

Right now, Bradley is currently in the care of a residential treatment facility.

While her son Aiden can communicate what he wants and pout when he doesn’t get it, Bradley is non-verbal and has autism. Unable to use words to communicate his feelings, he often speaks through aggression.

“He would wrap his whole body around your legs and bite you. And it would be to where for a year I had a piece of flesh that was just misshapen on my leg. He’s just very, very strong,” Bonaccorsi explained.

It’s children like Bradley, that are at risk of being abandoned to the state’s child welfare system.

Child Abandonment

While participating in the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism 2020 Data Fellowship, 11Alive's investigative team, The Reveal, learned about 40-percent who come into Georgia's care through forms of abandonment are teens.

Of the children with a diagnosis listed, 58-percent have severe behavioral or mental health challenges, 40 percent have a developmental disability. More than a third come into care with both.

The Reveal investigator Rebecca Lindstrom talked with more than two dozen parents and child welfare organizations about why parents walk away from these children. They all shared the same concerns.

They explain it as a complicated, fragmented system of care that doesn’t do a very good job coordinating its programs.

Depending on who has custody of the child, there are potentially four different state agencies involved in providing care: the Departments of Community Health, Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities, Education and the Division of Family and Children Services.

Between them, there’s little to no case management looking at the big picture. Just as frustrating, the child’s primary diagnosis – like bipolar or autism – can greatly limit the type of services and support available.

“The analogy, I would say is if you need vegetables, getting more hamburger isn't really going to help. And sometimes parents honestly deal with what they can get rather than what they need,” Devon Orland said.

Orland is the Litigation Director for the Georgia Advocacy Office, a federally mandated protection and advocacy non-profit that helps parents fight for what their child needs and what the state is legally mandated to provide.

“Once a child qualifies for Medicaid, that comes with certain commitments. You're legally entitled to a case manager, you're legally entitled to support within the home, and you're legally entitled to not have to fight, scrap and go broke doing it," Orland explained.

Orland is talking about EPSDT: Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnosis and Treatment Benefit. Created by Congress in 1967, it mandates those 21 and under covered by Medicaid have access to services needed to identify and treat physical, developmental, and mental health conditions.

According to the GAO, it's the Department of Community Health that is ultimately responsible for making sure EPSDT services exist and that there’s proper funding for access to them. Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities also manages access to those services that involve mental health and developmental disabilities.

The problem, there are really no consequences for states that fail to do so. That leaves families like Bonaccorsi, whose son qualifies for Medicaid because of his disability, fighting for services.

#KeepingBradley

For years, Bonaccorsi tried to get Bradley behavioral therapy, but all she received was a slot on a waiting list. Georgia covered the service, but there weren't enough therapists available.

At the age of 11, he broke the handle off a car door trying to get to his mother, who had fled to safety inside it, holding Bradley’s then baby brother, Aiden.

Unwilling to take no for an answer any longer, April sat with her son in an emergency room for several days, waiting for a bed to open up at a residential treatment facility. But after a few days at a location in metro Atlanta, staff declined to offer him further care.

That’s how Bradley ended up at Springbrook Autism Behavioral, a treatment facility in South Carolina, four hours away from their home. The distance makes visitation and involvement in his care difficult.

“I thought, this is going to be a couple of months and he’ll come back and we will have a plan on how we can help him on the daily, how I can help de-escalate and things of that nature,” Bonaccorsi explained.

But two years later, she says her family still has none of that, despite the fact Medicaid insists that level of care is no longer a medical necessity. And it probably wouldn’t be if Bonaccorsi could find local therapists trained and willing to work with him at home.

That too is a common problem according to parents. Insurance denies a higher level of care, knowing full well there is no other option available.

“At discharge, services in the community and in the home must be identified, approved and ready to go,” Joe Sarra, an advocate in the GAO’s protection and advocacy for individuals with developmental disabilities unit, or PADD, said.

Sarra also points out, the Americans with Disabilities Act requires that people receive care in the most integrated setting. That means, if Bradley can be treated in the community instead of a residential treatment facility, then he should be. And it's the responsibility of the state to make sure that care is accessible to him.

Bonaccorsi reached out to the GAO when she felt pressured by Medicaid to bring Bradley home regardless. When she pushed back, she says her insurance offered a solution.

“Well, you can give up partial custody to DFCS and then he’ll get the resources that he needs," Bonaccorsi recalls.

She says that is the problem, not Bradley’s aggression. The services should be the same, if not better, while in her custody and she should be able to find them at home. And to be clear, in reality, state custody comes with no guarantees either. The only flexibility DFCS has, is the ability to pay with state tax dollars in cases where insurance denies the care.

But in that moment of exhaustion, parents like Bonaccorsi do wonder, would their child be better off?

“Your mental health will decline. It’s just a lot,” Bonaccorsi said.

She never did give up custody and DCH has agreed to extend his stay at Springbrook while they search for therapists to work with him at home.

The family is in the process of moving into a new house, in a community where they hope therapy will be easier to access. She also wants in-home support to help de-escalate situations for safety, but as the state’s services are set up, Bradley won’t likely receive that kind of support until he turns 21.

Sarra argues, “if a medically necessary service is prescribed, the state must provide that service even when it is not part of the state Medicaid plan. When the service is lacking, the child's rights have been violated.”

But outside of a lawsuit, it’s hard to enforce those rights if the state declines the service.

Bonaccorsi says she’s determined to find a solution to get Bradley home and keep her other two children safe. Without him, the house just feels empty.

“It’s not really the house, it’s me. I feel empty without my child. Sorry, I’m going to cry,” Bonaccorsi said. “I feel empty without him. The house is always noisy because I’ve been a mom for 14 years. It’s just how I feel on the inside. I’m missing a huge piece.”

ABOUT THE DATA: We asked for data on all of the children that came into DFCS custody from 2016 to 2020 for abandonment, relinquishment, child behavior, and inability to cope. There were more than four dozen diagnoses associated with those children. We categorized those diagnosis into developmental, mental/behavioral, and medical for our analysis.

This story was told as part of a 2020 Data Fellowship with the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism.

The Reveal is an investigative show exposing inequality, injustice, and ineptitude created by people in power throughout Georgia and across the country.