'It could have been prevented' | Medical staff didn't take inmate’s complaints seriously, he died hours later, officer says

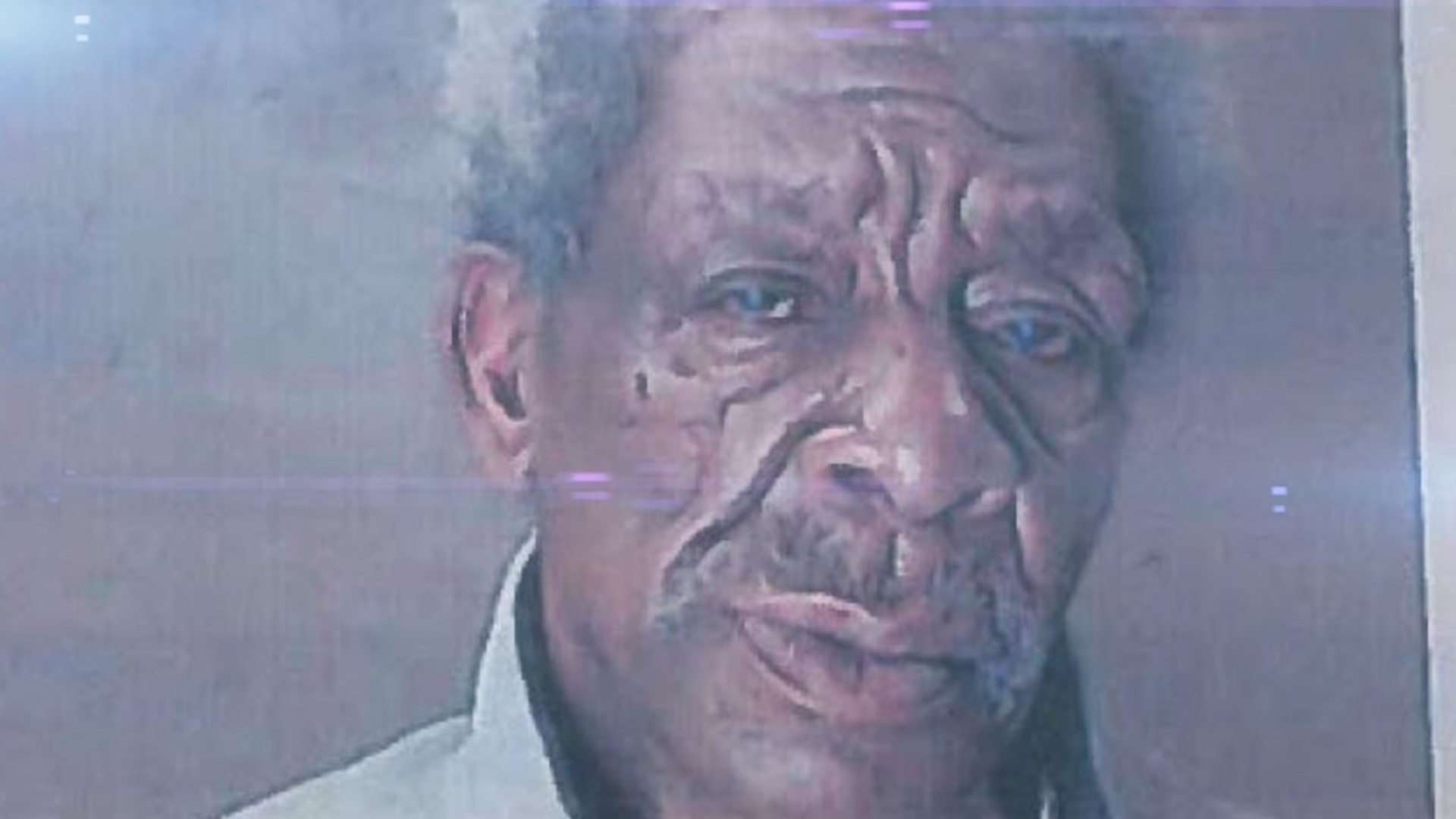

Clarence Manning's death inspired protests outside the DeKalb Co. jail in 2019. The public didn't know the circumstances of his death - until now.

A DeKalb County detention officer said she believes a man’s death could have been prevented if the jail’s medical staff took his cries for help seriously.

Clarence Manning died in May 2019 while detained inside the DeKalb County Detention Center.

The officer’s claim was discovered by The Reveal, 11Alive’s investigative team, in records recently made available to the public.

According to internal affairs records, sheriff employees announced a “signal two” on the radio on May 11, 2019 just after 1:00 p.m. for Manning. That radio signal meant deputies needed the infirmary to immediately respond to an inmate having a medical emergency.

However, it would take multiple requests from frustrated sheriff employees before medical staff eventually arrived.

“He seemed shaky. In my opinion, he didn’t seem as if he would be able to sit up,” said Sgt. Sonya McKinney during an interview with an internal affairs investigator about the incident.

Yet, McKinney wasn’t the only sheriff jail employee concerned with Manning’s health that day.

Malaysia Richardson, another detention officer, stated “As I was rolling the wheelchair out of the room, he just started shaking. He wouldn’t stop shaking."

Security video recorded inside the jail shows the 64-year-old inmate appeared to be having a seizure while sitting in a wheelchair surrounded by multiple jail employees.

A short time later, the U.S. Army veteran went unconscious and never woke back up. According to the county medical examiner, Manning died of a strangulated indirect inguinal hernia, which means the blood supply to his intestine was cut off.

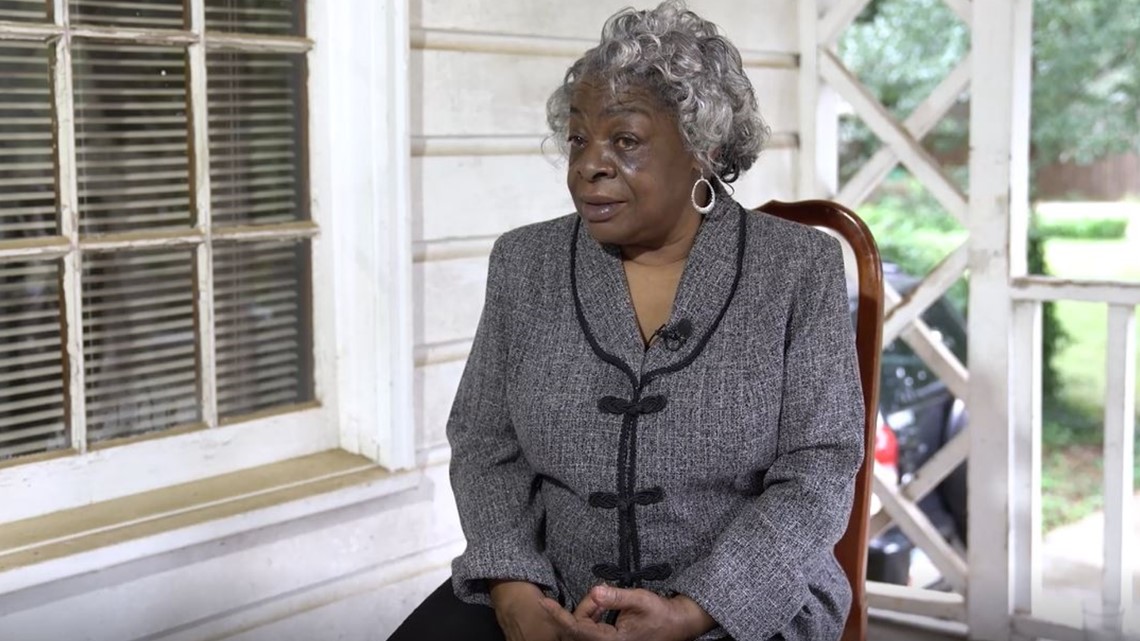

Manning’s sister, Shirly Nelson, said the county sent a deputy and a chaplain to break the news. “They were telling me they were doing an investigation and they would let us know, which they never did,” she said.

Four days after Manning died, dozens of people protested outside the jail, concerned with inmate treatment. They did not know the circumstances of Manning’s death at the time.

Chapter 1 Medical Care Denied

More than year later, audio recordings from the internal affairs file help paint a picture of what went wrong. They include interviews with multiple officers who voiced concerns with the medical staff’s response.

Officer Richardson said a nurse told her there was nothing wrong with Manning after issuing the signal two call for help. “[The nurse] said, ‘We just had a signal two from that same inmate. Nothing's wrong with him. He's got a hernia problem. That's not a major issue. He’s going to be in pain sometimes,’” Richardson explained.

Tinisha Ransome was one of the detention center’s doctors at the time. During a recorded interview, a sheriff investigator appeared baffled with Dr. Ransome after learning it took two officers, a sergeant and a lieutenant to convince her a wheelchair was needed to pick Manning up.

“If three, four different people have called you and said, ‘Hey, we need medical to come up to get him,’ the question should no longer even be, ‘Can he walk?” the investigator said.

“No, we just try to get an idea of what's going on,” Dr. Ransome said.

The sheriff investigator pushed back, adding “There's obviously something wrong when that many people that are calling to say, ‘Hey, I need medical to respond to come and get him,’ There is an issue there."

According to Manning’s records, medical staff knew he had issues with his hernia for months. He first notified them on Feb. 19, shortly after he was booked following an arrest for assault.

On March 4, Dr. Ransome noted Manning's condition in his chart.

The day before he died, officers alerted medical staff to Manning at least two different times for intense hernia pain. Each time, they explained that he was suffering from intense pain and could barely walk. A nurse even documented that Manning asked to go to Grady hospital but it never happened.

Officer Richardson made it clear who she thinks is at fault. “I feel like it could have been prevented,” said Richardson. “But, I don't think medical perceived it as being serious.”

Manning’s sister echoes the same outrage. “If they got him and probably transported him to the hospital right then, it could have been prevented,” she said. “Nobody deserves to die like that.”

Attorney Natalie Woodward represents Manning’s family in a wrongful death lawsuit. She believes the liability falls on the medical staff.

“At the end of the day, the deputies and the correction officers are at the mercy of the medical providers,” Woodward said. “The medical providers are contracted companies that the county contracts with and the counties depend on to give this medical care to.”

Over the past 10 years, DeKalb County has paid a company called Wellpath about $9 million a year to staff the jail’s infirmary.

The company declined an on-camera interview.

Dr. Ransome also never responded to The Reveal’s requests for comment. According to her LinkedIn profile, she left the company about a month after Manning’s death.

A Wellpath spokesperson eventually sent a one sentence response. “Wellpath has a policy of not commenting on pending litigation, and out of respect for both the Manning family and the legal process, we believe that further comment would be inappropriate at this time,” said Judy Lilley, the company's vice president of corporate communications and public affairs.

Sheriff Melody Maddox also declined to respond to Manning’s death or the medical staff’s actions that day, though the county is not named in the lawsuit.

Since Manning's death in 2019, four more detainees have died and since 2001, 75 people have died while in the county’s custody.

Most of the people who died were not convicted of the crimes. They simply were too poor to bail out jail and wait for their day in court, just like Manning.

Chapter 2 History of Complaints

Wellpath, a billion dollar medical company, has contracts in jails and prisons in 34 states and is no stranger to criticism over the care it provides to detainees.

According to the Project On Government Oversight (POGO), a nonpartisan independent watchdog group, at least 1,400 lawsuits have been filed against Wellpath and Correct Care Solutions, the company it merged with in 2018.

WellPath addresses the number of lawsuits filed against it on its website, ranging from medical practice, to wrongful death and claims made by former employees.

"Any person may file a lawsuit, especially in a restricted environment such as a jail or prison," the company stated. "Only about 7% of the lawsuits filed against Wellpath have resulted in a payment of any kind.”

This past June, a Texas woman filed a lawsuit alleging she had a miscarriage after she was denied medical care from a detention facility which used Wellpath as its medical provider.

“They didn’t treat me like a human,” the woman in question, Lauren Kent, told WFAA-TV. She was detained in Collin County, Texas in 2019 for unauthorized use of a debit card. She was three months pregnant at the time.

"Wellpath is aware of the referenced lawsuit. Because litigation is ongoing and involves detailed personal and medical information regarding a patient, we are unable to comment or provide details at this time," a Wellpath spokesperson told WFAA in a statement.

In 2020, a Virginia judge approved an $800,000 settlement in a lawsuit against Correct Care Solutions, which merged with Wellpath two years before.

According to that lawsuit, also reported by WAVY-TV, jail staff ignored an 18-year-old man’s medical condition and returned him to a cell. He died the next day of diabetic ketoacidosis, caused by a lack of insulin.

In 2019, an investigation conducted by CNN found former Correct Care Solution and Wellpath employees who claimed the companies didn’t do enough to care for inmates.

Among those who talked were two nurses who worked at a correctional facility in Memphis, Tennessee. They claimed the company sometimes denied inmates medication if it was too expensive.

“If it cost too much, oh well,” said Crystal Tucker, a former nurse for WellPath, who said she was fired for speaking out.

A Wellpath doctor interviewed by CNN said the company does not put profit ahead of care. “Our staff are told never to allow financial anything, even their perception, that they should be somehow saving us money,” added Dr. Cassandra Newkick, Wellpath’s Chief Psychiatric Officer at the time of CNN’s story.

The company reiterates that position in a post on its website. “[T]he notion that privatization creates tension between patient care and profit couldn’t be further from the truth. Wellpath’s business is grounded in providing excellent service and adding value for our clients,” said Wellpath.