Transparency should apply to our lawmakers too

<p>Do you want to see the laws of the state of Georgia? You will need to spend nearly $400 to purchase a copy. One man – Carl Malamud – tried to fix that – and now Georgia's state lawmakers are suing him.</p>

ATLANTA – Do you want to see the laws of the state of Georgia -- the laws of the land, that your elected officials have written and voted on under the the Gold Dome during each legislative session? You will need to spend nearly $400 to purchase a copy.

One man – Carl Malamud – tried to fix that – and now Georgia's state lawmakers are suing him.

The General Assembly is suing Malamud in federal court because he dared to publish all 50 volumes of Georgia law online – for free.

“America is based on an informed citizenry, because ignorance of the law if no excuse: If you don’t know what the law is, you can’t obey it, but also, you can’t change it,” said Malamud. “And America is based on the idea that citizens are able to read the law, and go to their legislature and say, ‘I don’t like it, let’s do something differently.’”

Malamud’s site – public.resource.org – is the defendant in a copyright infringement lawsuit filed by Georgia’s General Assembly.

“In America, the law isn’t owned by governments,” Malamud said. “It’s owned by the people, because it’s the people that give authority to the government to operate. The people own the copyright on the law.”

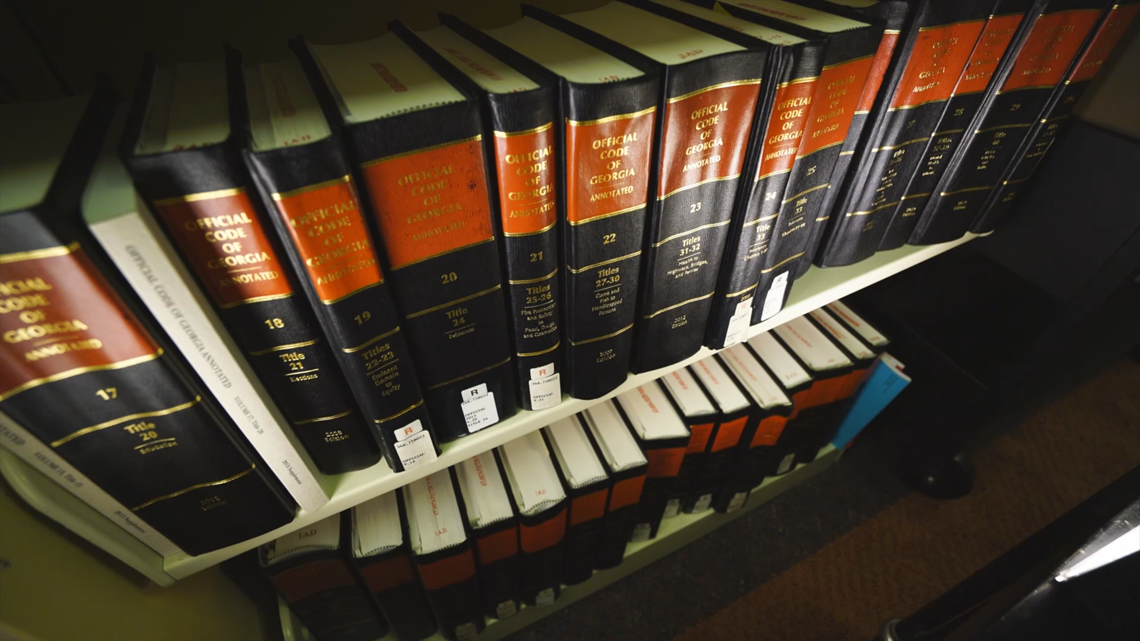

The O.C.G.A. – “The Official Code of Georgia, Annotated,” are comprised of 50 volumes – the state’s official law books, which contain all the legislative acts, plus public court cases and attorney general opinions.

Lawmakers claim putting those “annotations” together amounts to a “creative work” – one which the state has copyrighted.

“There’s only one law in Georgia – it’s the Official Code of Georgia, Annotated,” Malamud said. “Every act in the Georgia Assembly begins, ‘An act to amend the Official Code of Georgia, Annotated.’”

The 11Alive Investigators asked to inspect the law books under a measure contained within them – Georgia’s Open Records Act.

The Legislative Counsel, Wayne Allen, denied our request, suggesting the Law is “available at many libraries.”

We had trouble finding the Law at three local public library branches – including the central library in Georgia’s capitol city, mere blocks from the state capitol building.

There is a set at the public law library directly across from the Georgia State Capitol, but cameras are not allowed inside without an order signed by a judge.

Atlanta’s main library keeps its copies out of sight in a back room, where we had to request special access to photograph the volumes – some copies of which are not close to current at all – and dating back more than six years.

“It just doesn’t make sense in an internet era to say you need to travel 30 miles to the county seat to look at the 50 volumes of paper, and that’s somehow making the law accessible to you,” said Malamud. “It isn’t.

The Legislative Counsel wrote that we could purchase the Law for $378 “like anyone else,” but warned us not to publish Georgia laws on 11Alive.com, saying the O.C.G.A. is “copyrighted by the state of Georgia and shall not be reproduced without permission. No permission is granted here.”

That response reflects every attempt we’ve made to get documents from state lawmakers.

Transparency means we all get to see government documents from every agency – from the dog catcher to the governor. But the Legislative Counsel always replies “your request is denied” – reflecting a lack of transparency that allows the legislature to do deals under the table because you and I aren’t allowed to see the documents.

11Alive’s Brendan Keefe asked several Georgia lawmakers if they were aware that the state’s General Assembly was exempt from the state’s own Open Records Act.

“Were you aware the General Assembly is exempt from the Open Records Act?” Keefe asked Georgia State Representative Clay Pirkle (R-Ashburn).

“I was not,” Pirkle replied. “No.”

Keefe asked the same question of state Senator Lester Jackson (D-Savannah). “Were you aware that the General Assembly is exempt from the Open Records Act?”

“I did not know that,” Jackson replied.

But ask to see any documents from a legislator, and you’ll hear from their lawyer – a lawyer your tax dollars are paying for. That’s right. Georgia tax dollars pay Legislative Counsel Wayne Allen to the tune of $125,000 a year so he can turn around and deny your requests to see the people’s records.

“What’s this about?” asked Georgia state Sen. John F. Kennedy (R-Macon).

“About transparency, open records, things like that,” Keefe said.

“I’d rather not – part of my concern is I’m the governor’s floor leader, so I want to make sure that I’m answering questions consistent with what the Administration would want me to, since I don’t know the questions,” Kennedy said. “Now, if you want to give me the questions, I’d be happy to.”

“So you want the questions in advance?” Keefe asked.

Here’s how lawmakers avoid questions about their documents – The General Assembly is “not an agency” under its own Open Records Act. The Legislature let itself off on a technicality – one few lawmakers are interested in fixing.

“If it ever came up for a vote that the General Assembly would be subject to the Open Records Act, would you be in favor of that?” Keefe asked Pirkle – one of the state representatives he spoke with earlier.

“Um, I’d just have to look at the legislation,” Pirkle replied. “The devil is in the details.”

Back to Kennedy:

“We just want to ask you about transparency,” Keefe said.

“If you want to give me the topic matter, I’d be glad to, but I’ve gotta run in here as well,” Kennedy said.

And with another state senator – DeKalb County Republican Fran Millar…

“Ought there to be full transparency – especially when it comes to the people who elected you?” Keefe asked.

“You know, I think you’ve got a fine line there,” Millar said. “I don’t have an easy answer for that.”

Neither does the legislative counsel. All communications between the counsel’s office and lawmakers are confidential by law. A staff member in the legislative counsel’s office was not happy with our cameras being present.

“May I ask what you’re taking a picture for?” a staff member asked.

“This is a public building,” isn’t it?” Keefe asked.

“Yeah.”

When they saw our cameras, legislative counsel staff was sure to draw the blinds – to protect the keeper – and defender – of the legislature’s secrets from public view.

“It’s the people that own the law, and it’s the people who own the legislature,” said Malamud. “We are servants of the people when we are in public service and we just can’t forget that.”Malamud. “We are servants of the people when we are in public service and we just can’t forget that.”

In that statement, Caldwell points out that the state's copyright on the O.C.G.A. has existed since 1982, and goes on to insist that the publisher of the O.C.G.A., LexisNexis, recieves no monitary payment from the state for producing copies of the Law, but recoups it investment from the copies it sells to the general public. Caldwell says the contractual agreement allows the General Assembly to produce an "official, reliable, updated, and affordable annotated Code, without expending taxpayer funds."

But back to the current federal copyright lawsuit: In today's internet age, why doesn’t the state just put the law online for free?

Georgia is the only state in the nation to sue public.resource.org for putting the searchable version of the official Georgia code online. The state of Oregon sent public.resource.org a cease-and-desist letter for placing that state's legal code online, but, then state officials there held hearings before deciding to keep the law online for free.

The state of Georgia does have a website available with the un-annotated version of the code, but you have to agree to terms and conditions before you can even see it. And, as it is the un-annotated version of the code, it is not the "official" O.C.G.A., that police officers cite during arrests, or courts work from during proceedings.

The federal copyright suit has hearings later this week.