Workers claim company exposed them to cancer-causing chemicals

Around a dozen workers, including Demetrius Phillips who died from cancer in August 2021, claim the company they worked for exposed them to dangerous chemicals.

The lawsuit

An Atlanta judge could soon decide if a trucking company that hauls dangerous chemicals across the country is liable for making some of its employees sick.

The trial, which begins Friday, will also shed light on a job, experts said is dangerous and antiquated.

The lawsuit involves Trimac, one of the largest transportation trucking companies in North America, with two facilities in metro Atlanta.

This week’s case focuses on a workers' compensation claim filed by Demetrius Phillips, who died from cancer in August 2021. Administrative law judge Kimberly Boehm will hear the case.

Phillips, and about a dozen former employees, claim Trimac and chemical companies exposed them to cancer-causing toxins by requiring them to crawl inside tanker trucks to remove chemical residue without proper protective equipment. Those claims involve two different lawsuits pending in Fulton County State Court.

The employees also allege Trimac failed to keep them safe by not telling them some of the chemicals they removed were hazardous.

"He did say that he was kind of scared, saying that he felt that it was dangerous," said Nicole Milan, Phillips’ widow. "But, he said he had a family to feed and he didn’t want us to go without."

The 51-year-old father worked at Trimac’s Fairburn, Georgia facility for 13 years, crawling inside tanker trucks up to 25 times a day. The company also operates another location in Atlanta.

Milan said her late husband start falling ill in 2019. A trip to the emergency room soon revealed he had lymphoma.

"When I first heard cancer, I automatically thought the job and the chemicals," Milan said.

Toxic Jobs | Workers claim company exposed them to cancer-causing chemicals

Trimac told Phillips his job was safe. Before going inside its tankers, the company shows employees tank entry permits which identify the what kind of product was last hauled inside and whether it was hazardous or not.

An 11Alive investigation shows employees were not always told the truth.

Part of the lawsuit includes about dozen tank entry permits, showing some chemicals last hauled were ethylene, diisocyanate, and acid. All are chemicals the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) identifies as potentially lethal, or cancer-causing, if exposed or inhaled.

Trimac listed each of them in the permits as non-hazardous.

Pamela Pollet is a professor at Georgia Tech’s School of Chemistry and is its safety program coordinator. She reviewed the permits as a paid expert witness for the former employees.

"You have hard-working individuals that unfortunately have no knowledge of chemistry or toxicity that were misled," Pollet said.

One of the entry permits she reviewed includes a tanker that last hauled MDI, or methylene diphenyl diisocyanate. It’s a compound the EPA said can be fatal, but Trimac identified it as non-hazardous. Pollet said even an ounce left in a tanker could be dangerous to a worker if they don’t have the proper protective equipment.

"We computed how much you will need to reach this I.D.H.L, this Immediate Danger to Health and Life, and that is very little because those chemicals are so toxic and so dangerous,” said Pollet.

Trimac declined 11Alive’s requests for an interview, citing pending litigation. Instead, it sent a letter the company said it provided to its employees informing them about the lawsuit.

The letter called the former employee’s claims "simply untrue." It also told staff that it takes the claims very seriously.

"The health and safety of our employees and the community are paramount," the statement reads.

Trimac said it was aware of "efforts to garner media attention to the case" and that depositions, video and documents that are taken out of context can "leave out key information about the overall testimony and true facts in the case.”

Phillips’ widow believes the trial will show Trimac is responsible for her husband’s death.

"I just think about other families and hoping that no one has to endure what me and my kids have to endure," Milan said.

A history of violations

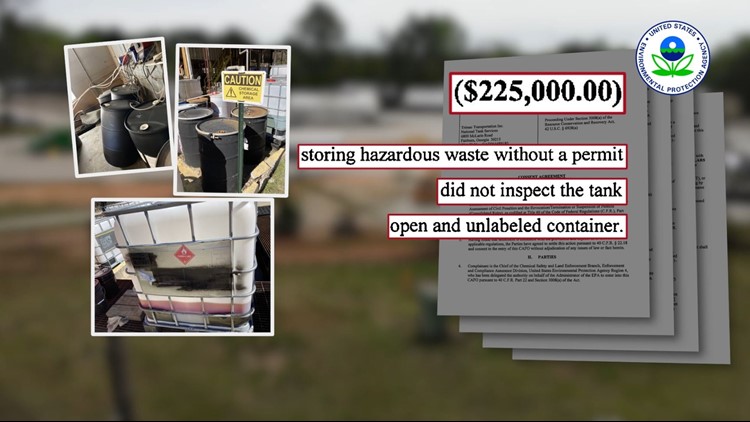

About two years ago, Trimac paid a $225,000 penalty to the EPA after the agency cited it for multiple violations at its Fairburn facility, including storing hazardous waste without permits, and failing to inspect tanks and unlabeled chemical containers.

Despite a consent order where Trimac promised to address the violations, inspections earlier this year discovered similar problems.

This past January and February, a judge ordered Trimac to allow Pollet, and the law firm representing workers, access to inspect its facilities in Fairburn and Atlanta.

Trimac had at least a month’s notice before the inspection, but Pollet still identified barrels of chemicals not labeled, unknown liquids near electrical wires, and multiple broken wash stations that are meant to be used to rinse workers in case of an exposure.

Pollet described the facilities as "dangerous."

While the company said it welcomed the inspection, court filings show it tried to prevent Pollet and attorneys from accessing the facilities multiple times.

In June 2021, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) cited Trimac for multiple violations, including failing to provide proper respiratory equipment to employees, non-working eyewash stations in the event of an emergency, and fire hazards.

The company paid OSHA $12,392 in fines to settle the penalties.

In 2016, inspection records from the Georgia Department of Natural Resources show the agency cited Trimac for failing to document an emergency plan to local police and fire departments and "maintain on-site weekly inspections of hazardous waste accumulation."

Still in practice today

Trimac believes workers must go inside tankers to adequately remove and clean out chemicals left inside.

"Confined space entry is necessary in this industry," Leah Miller, the company’s director of communications, said in an email to 11Alive.

Trimac said OSHA has strict rules in place that allow workers to safely do the work. The company also pointed to a blog post on a freight broker’s website that details why the practice is needed to prevent cross-contamination of chemicals.

"After the wash, some trailer tanks may require an additional round of cleaning and, in rarer cases, the tank may require a tank wash facility specialist to enter the tank and apply steel wool or perform spot cleaning," the blog reads.

Pollet, who has consulted chemical companies for years, said she was unaware humans were going inside the tankers to remove the chemicals.

"Absolutely, there must be a better way to do this. We do not expose the lives of individuals in that way," said Pollet.