We’ve heard a lot about the mass shooting in Texas and all the ways the system failed.

Here’s why this issue is so important:

More than half of domestic violence homicides are committed by people prohibited from having a gun. Overall, 42 percent of domestic violence murder victims are children and more than half of all mass shootings are domestic violence-related.

11Alive has found there’s a gap in the law right here in Georgia that’s allowing domestic violence abusers, banned from having a gun, to keep them anyway.

Just 6 days after the court ordered James Bland to stay away from his wife and children, he crawled nearly a mile through the woods, crossed a creek and hid on the side of the house. As the garage door started to close, Janet Paulsen made a terrifying discovery.

“I saw him in the side view mirror leaning against a wall - 2 feet from me - cocking a gun,” she said. “So, I put my head down, I put the car in reverse.”

But instead of the street, she hit a tree - then the ditch. She crawled out the passenger side door hoping to run to safety.

“He shattered my right femur,” she said. “He shattered my left knee; I have a shot that mangled my right lung.”

She managed to get a short distance further before Bland stood and shot his wife two more times.

“And I watched him do it,” she said.

At that point, there was nothing about him that she recognized.

“This was pure evil; I can’t describe the look,” she said. “It was emotionless; it was expressionless - but so much so that it was evil.”

As soon as Paulsen filed for a temporary protection order, the Cobb County Sheriff’s Office seized 71 guns belonging to Bland.

But he still had one more and she knew where he kept it.

“In his vehicle,” she said.

She told officials about it, too.

“I was told it was a gray area,” she said. “A protective order does not cover the inside of the vehicle - even if it’s on the property.”

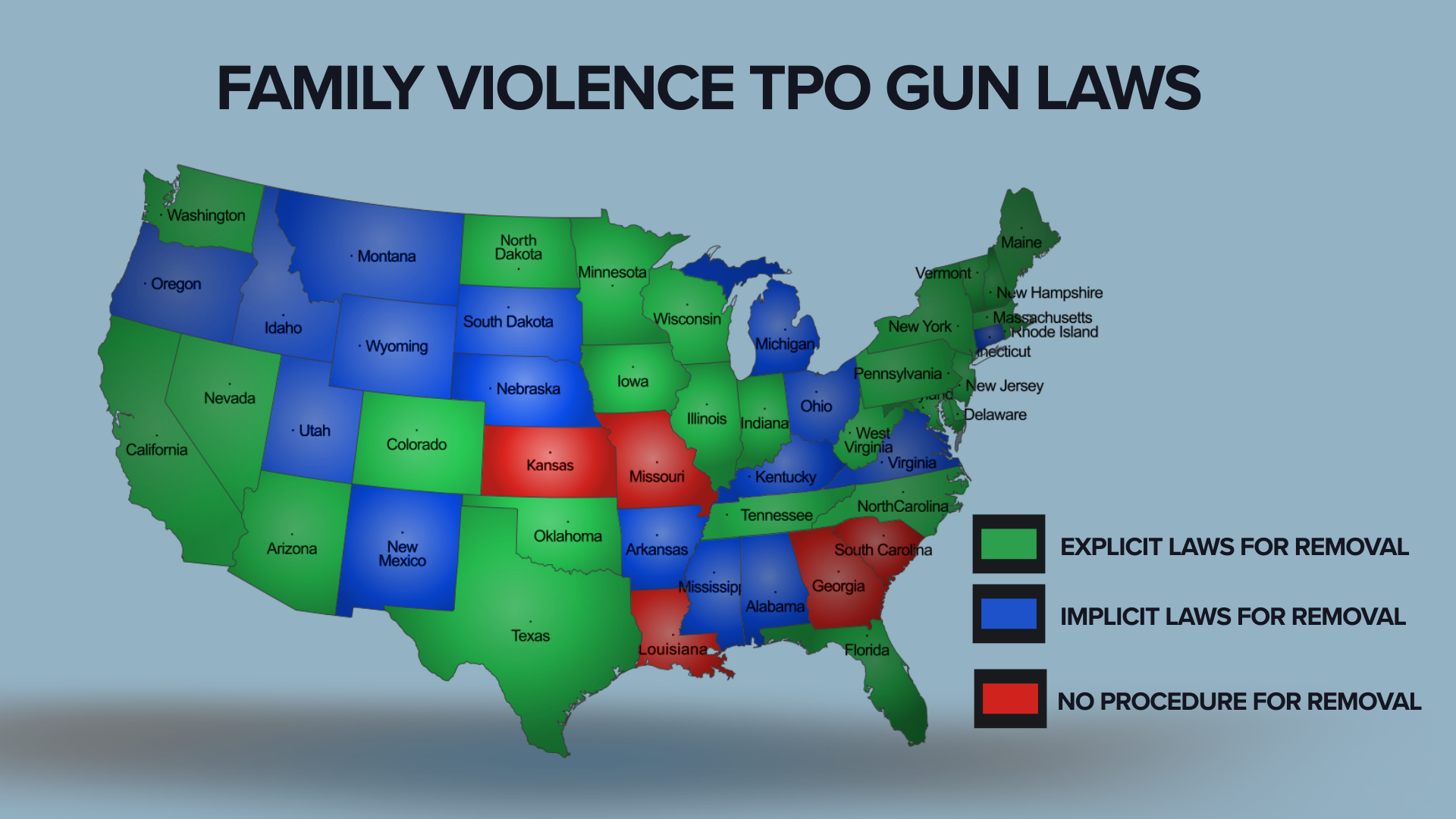

To be clear, federal law prohibits anyone served with a family violence protective order after a hearing, from possessing a gun. But Georgia is one of five states with no law at any stage of the process to give implicit or explicit authority to enforce the federal law.

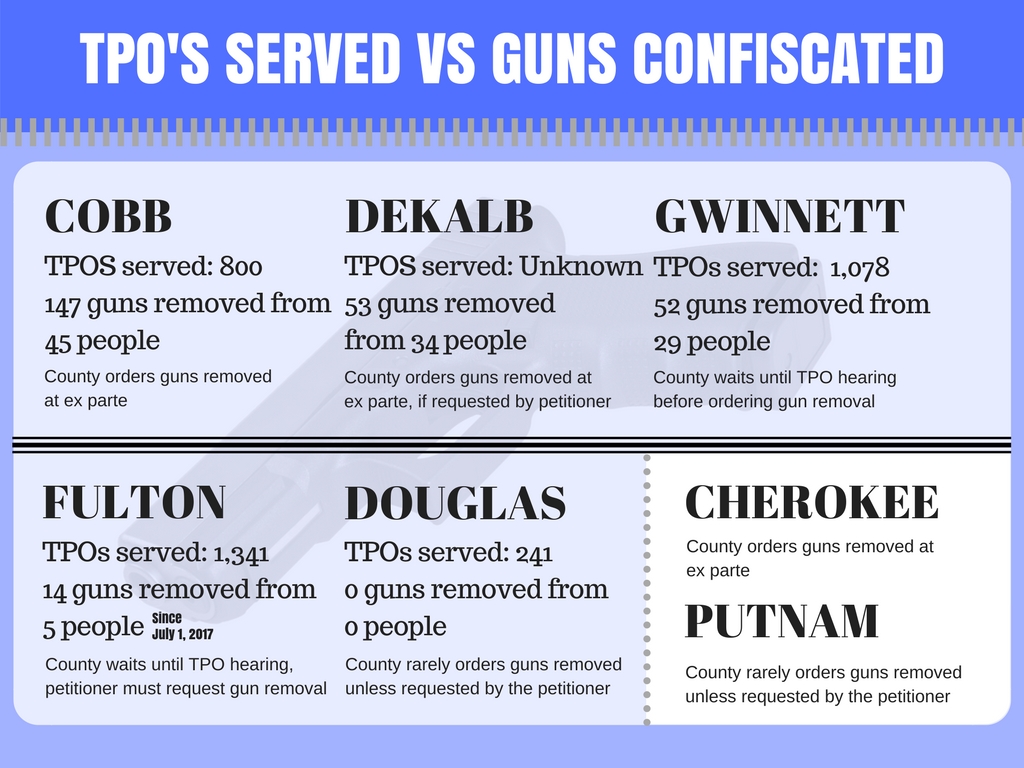

That means it’s up to counties – and even individual judges – to decide how seriously to take the threat.

“It’s not just cut and dry,” Sgt. Tracy Lee with the Gwinnett County Sheriff’s Office said. “It can vary.”

There are two parts to a family violence temporary protection order. The ex-parte is usually granted the day it’s filed, offering immediate legal protection. But Sgt. Lee said it also offers immediate personal risk.

“That’s the moment of truth,” he said. “That’s when you’re going to find out if he or she is going to back off or they’re going to come after you with everything they’ve got.”

Because of that risk, judges in Cobb, DeKalb, and Cherokee generally order respondents to surrender their guns immediately. But investigator Rebecca Lindstrom found some counties that rarely order a respondent to surrender their guns unless the petitioner came into specifically after being threatened with the weapon.

Other counties, like Gwinnett, are concerned about removing weapons from a potential abuser but believe due process must be served first. In those counties, judges wait a week or so until both parties can attend a scheduled hearing, allowing the judge to hear the full story.

“At that point, they will ask the respondent, ‘Do you have a firearm?’,” he said.

It’s up to the respondent to tell the truth.

And, sometimes, it’s a situation that leaves Sgt. Lee with a feeling in his gut that someone isn’t telling the truth.

“Oh, all the time,” he said.

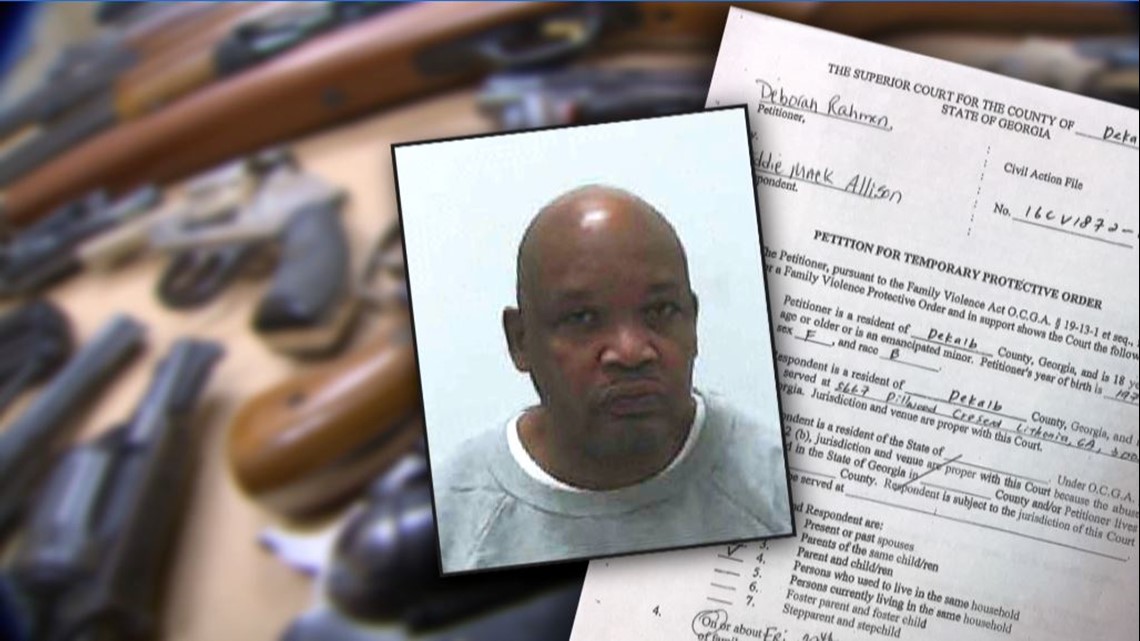

Just hours after Eddie Mack Allison was ordered to surrender his firearm by a Dekalb County judge, he shot his wife in a CVS parking lot three times.

Even though Deborah Rahmen told the court her husband had taken “out his gun” and threatened to “blow my brains out” there is no paperwork to indicate the deputy even asked Allison for his gun. The deputy was never disciplined for failing to follow the court order.

“There’s no teeth,” Rep. Brian Strickland said. “There’s no mechanism in the law to make sure those guns aren’t actually in that person’s hands.”

Strickland knows there are counties in this state that rarely ask a respondent to surrender their weapons. He’s introduced HB541 to change that.

“If you support the current law I think you ought to also support a mechanism to enforce that law,” Strickland said. “I am very open to different ideas on how we do this … Something has to be done."

Some states allow respondents to sell their weapons and provide a receipt to the court. Others allow a third party to get court approval to store the weapons. The most common method is to have the guns stored temporarily by law enforcement.

Sgt. Lee said there's more to this though than removing guns. The Gwinnett County Family Violence unit with the Sheriff's Office stresses safety plans, counseling, and spends time with respondents to explain why they need to stay away.

The county went 6 years without a TPO petitioner being killed by an abuser. Even now as the judicial system determines whether that stretch has been broken, the weapon used in that case was a knife, not a gun.

That's why Paulsen said that, beyond the discussion of guns, we need to look at how we treat those who violate a TPO.

"If you violate a protective order you obviously have no regard for the judge's order. That makes you even more dangerous," Paulsen said.

She believes a respondent who violates the order should remain behind bars until their hearing.

Paulsen's husband died at the hospital. Technically, so did she. But a trauma surgeon was able to massage her heart back to life.

She has an L2 spinal cord injury and only 30 percent of the muscles in her right leg still work, but she's determined to keep up her physical therapy at the Shepherd Center.

Her walls are filled with inspirational quotes and her heart is filled with gratitude for those the medical professionals that helped save her life, as well as the community that has helped her rebuild it. She has twin boys in high school -- and plenty of reasons to live.

Paulsen now keeps a well-worn piece of paper in her purse covered in names.

“There were 529 people killed in the state Georgia, just in domestic violence gun shootings in 5 years,” she said.

At a vigil, as names were called, and lives remembered, Paulsen said she couldn’t forget that her name was almost the last one on this list.

“It’s mindboggling how much damage one person - one person - can do,” she said.

Overall, that’s worked. But Janet said the rules shouldn’t vary from county to county and it shouldn’t be up to domestic violence victims to ask.

Every state around Georgia except South Carolina has already passed some kind of law to enforce the federal rule. Some propose giving gun owners a chance to sell their weapons or surrender them to a court-approved family member or friend.