ATLANTA — After 75 years, some recognition is coming to a group of men who were the first African-Americans to take the ultimate leap into war. Their mission and story were rarely discussed, but now a bill signed into law is going to change all of that.

“I can be proud to say truly, I’m few of the last remaining Triple Nickels,” said Lt. Col. Daniel Boatwright of the 2nd Airborne Ranger Company - also an original member of the 555th Parachute Infantry Battalion aka the "Triple Nickels".

THEIR STORY

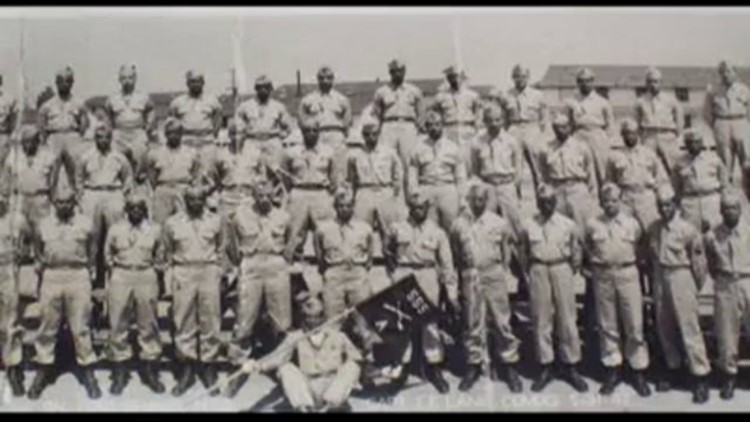

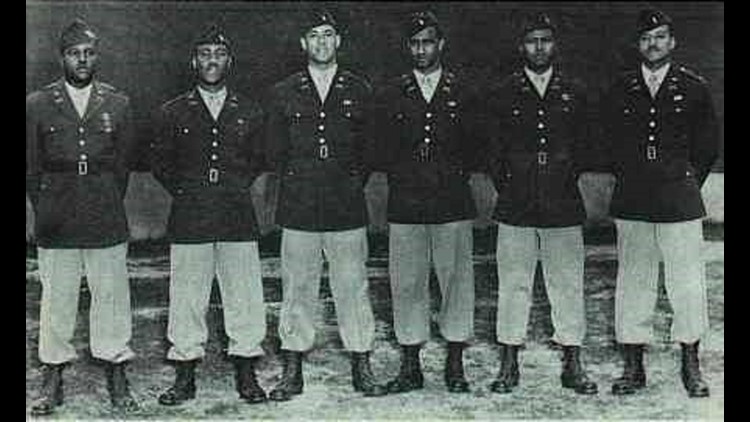

On Feb. 18, 1944, 16 soldiers became America’s first black paratroopers.

“It took me a long time to realize what we had done. When I first got out of the army I didn’t even talk about it. Over a long period of time, I realized we had given this country a great service,” said Sgt. Jordan "J.J." Corbett - a smokejumper of the 555th Parachute Infantry Battalion.

Many years before “Black Pride" became a popular slogan, Triple Nickel historian Timothy McCoy said this small group of black American soldiers gave life and meaning to those words.

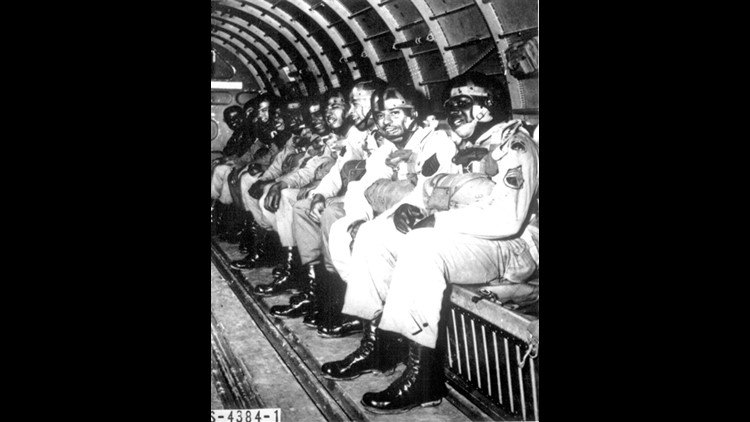

“They [white military personnel] took bets on the fact that they wouldn’t jump out of the plane ... but they did,” said Sgt. Wheeler Small, a member of 2nd Airborne Ranger Company.

They were thousands of feet in the sky and left any trace of hesitation on the ground.

“When we jumped, all of the chutes opened at one time. We were out there we didn’t care,” said Boatwright.

This battalion was leaps above the normal military service jobs black men had at that time.

“I didn’t like that service company I was in. That’s when I volunteered with the Triple Nickles to get the hell out of there. I would come home with trash stuck on my foot. I said this is not for me. So I took that leap.” said Boatwright.

The men said there was no task too difficult.

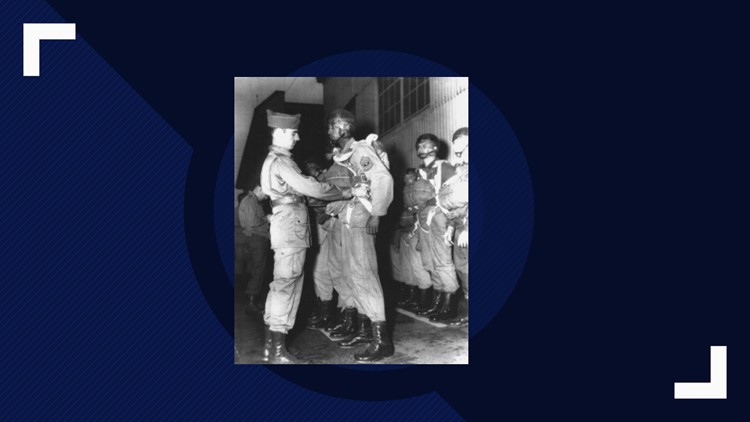

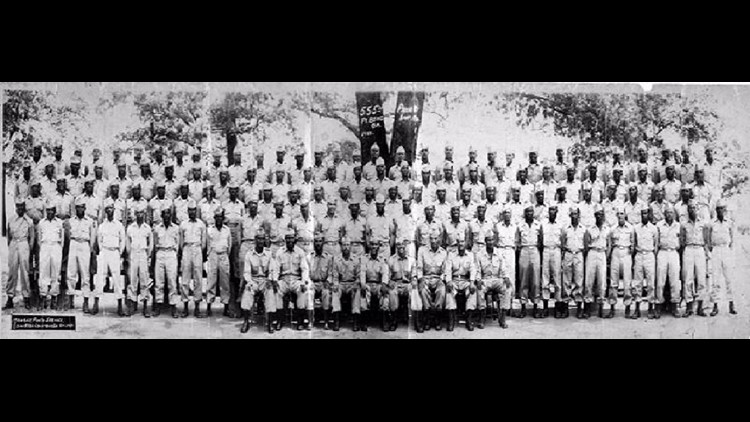

THEIR TRAINING

“Something about us -- we had to be better than everyone. We dress better, we marched better, we walked further. We knew one of two things every time we woke up... we’re going to run as far as you can run and do exercise,” said Boatwright.

Nothing could have prepared them for this training.

“When I went into the paratroopers, I was a football player but I had never had the exercises and things like that in order to prepare to be a paratrooper. They would wake us at 2 in the morning on a forest march ... we would march for hours with everything we needed.” said Corbett.

The drills prepared them for the war across seas, but it was no match against the enemy they’d fought all of their lives at home.

THE RACISM

“They would say they don’t trust us with a weapon or that we can't lead,” said Wheeler.

During that time, they were prisoners of segregation.

“Even one experience -- I was coming back on the train from Oregon into Texas. [We] wanted to go in and get a sandwich when the train stopped and we were not allowed to go in the front door and get a sandwich, but yet German prisoners were,” said Corbett.

But the men said keeping the faith was essential.

“The only thing black and white to me is white paint and black shoe polish ... that’s the only black and white I know," said Boatwright.

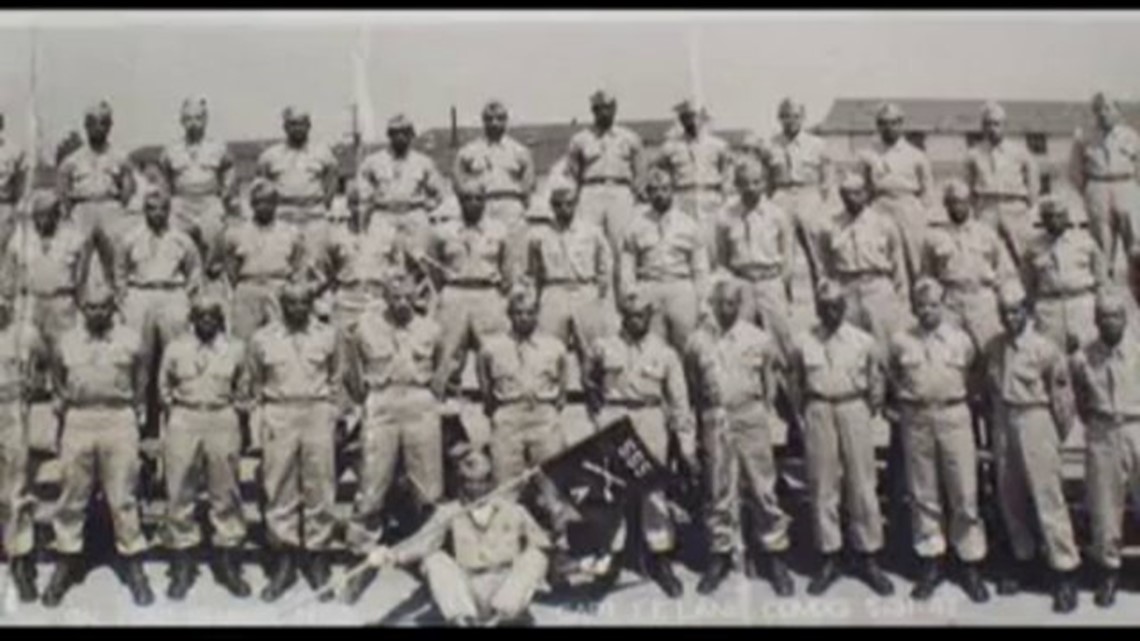

To prove that, they worked to be twice as good, because the Triple Nickels 1st Sgt. Walter Morrison expected nothing less than the best.

“We were all fighting to change things ... it was just going very slow. I think a lot of us wanted to go in and prove that we could be good Americans,” said Corbett.

Despite the hard work, the chance to prove it never came.

“The 555 [were] well-trained, ready to go to war. That’s what everyone wanted. They got this Black Battalion they don’t know what to do with,” said Small. "Why didn’t you all make it to WWII? No one wanted us.”

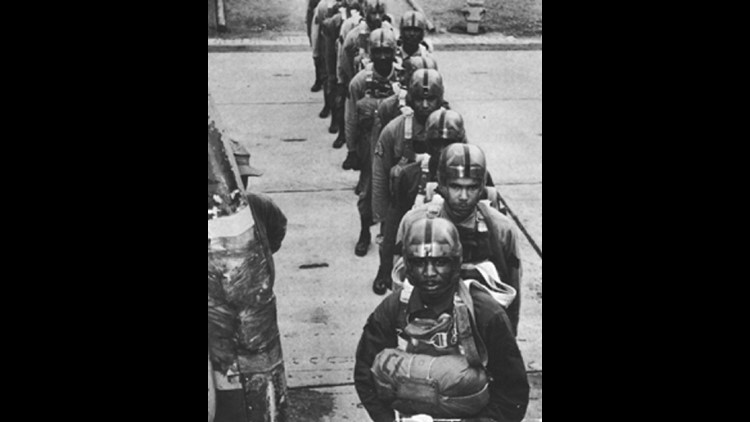

That changed when the Japanese sent over balloon bombs. That’s when a unit of the 555 known as the smokejumpers got their chance.

“We found out that the Japanese were sending incendiary bombs by balloon. That balloon was 35 feet in diameter; carrying 10 sandbags and 10 bombs, " Corbett explained. "One of the bombs did explode and killed a family of 6. They didn’t want to publicize it at that time ... we were sent out there to [deactivate] the bombs that didn’t go off and fight those forest fires.”

Their story didn’t make it to the public.

”At the end of the war at the victory parade in New York, guess who marched in it? Triple Nickels. But they cut the movie cameras off. You don’t see us. Only the Pittsburgh Courier took still pictures of us, but you don’t see us marching," said Corbett.

THEIR LEGACY

After 75 years, people will have the chance to learn about the Triple Nickels. President Trump signed a bipartisan bill to designate a United States Post Office in Columbus, Georgia, as the “Richard W. Williams, Jr., Chapter of the Triple Nickles (555th P.I.A.) Post Office.”

“I am honored to join my fellow Georgians and colleagues in Congress in honoring 555th Triple Nickles Parachute Infantry Battalion,” said U.S. Rep. Sandford Bishop, of Georgia's 2nd district. “They remain American heroes and pioneers on behalf of many African-Americans that followed in service.”

Most of them didn’t live to see the honor so long denied, but to the few who are left, it:

“Feels good,” said Boatwright. “If you see something you wanna know what it’s about.”

It’s a feeling that the sons, daughters, nieces and nephews of the Triple Nickels can appreciate -- and hold onto -- forever.

“I knew him as my uncle but he didn’t talk about it a lot. I knew he still had bullets in his body. He didn’t talk about his historic-ness. He didn’t brag.” said Lisa Parks, Boatwright’s niece.

But then again, real heroes rarely do.

Leaping into war | The first all black Parachute Infantry Battalion "Triple Nickels"

**Senator Perdue’s office is in the process of planning an official renaming ceremony at the post office. The post office will be named the "Richard W. Williams, Jr., Chapter of the Triple Nickles (555th P.I.A.) Post Office." Richard "Black Daddy" Williams was an Executive Officer in the Triple Nickel battalion. He lived in Columbus.

MORE |