People that you should know for Black History Month 2022

February is Black History Month, and every day, we will showcase a prominent figure in Black history.

February is Black History Month. Every day, we will showcase a prominent figure in Black history.

February 1-5

MARY DAVIDSON KENNER

Mary Beatrice Davidson Kenner (May 17, 1912 – January 13, 2006) was an inventor who received 5 patents. Kenner succeeded in patenting inventions that made everyday life easier. Her inventions include the sanitary belt -- a predecessor to the maxi pad, a serving tray and pocket that connect to a walker, and a toilet paper holder that ensures the loose end of the paper is within reach.

Kenner’s first patent came in 1957 for the sanitary belt, which was used to hold sanitary napkins in place. This was before adhesive maxi pads and tampons were invented. Although Kenner had invented the sanitary belt years before, she could not afford to file for a patent, and she experienced racism in her quest to obtain a patent. The company that first showed interest in her invention rejected it after they discovered that she was Black.

Kenner continued to invent in spite of obstacles. In 1976, after her sister was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis, Kenner patented a walker with an attachable tray and pocket for carrying items. In the 1980s, Kenner invented a toilet paper dispenser with paper that was always reachable, and a back washer that could be mounted to a shower wall.

Kenner passed away on January 13, 2006 in Washington, D.C. at the age of 93. Although she never received awards, fame or wealth during her lifetime, Kenner’s inventions had an enduring impact on everyday life.

SOLOMON HUMPHRIES

According to Macon historians and the 1993 13WMAZ documentary called "Black Cultural History in Macon, Georgia," Solomon Humphries opened the first Black-owned business in Macon. He was a freed slave in the 1830s who opened his business on Main Street. Before growing the business into what was known as a "general store," Humphries sold sandwiches, but it was the general store that made him wealthy. There, he sold clothing, food, and a variety of daily life needs of the era.

Humphries was so highly-respected that he not only was able to obtain credit for the store, but purchased the freedom of other Blacks in Macon. Those individuals also worked in the store.

However, while he became very wealthy, Humphries died poor. Historians say he allowed two white men to operate the business who “speculated” or spent his funds. In his later years, Humphries would run his own store.

Solomon Humphries' reputation was such that when he died in August of 1858, all the merchants in Macon closed their shops for an hour to attend his funeral. It was held at the Presbyterian Church in Macon and sermonized by a white pastor.

JOHN S. ROCK

An eloquent activist and master of several professions, John S. Rock (1825–1866) was born in Salem, New Jersey, to free black parents. Educated in the public schools, he was a grammar school teacher between 1844 and 1848 and also studied medicine while working as an assistant to two white doctors. After being denied admission to medical school, Rock studied dentistry and subsequently opened a dental practice in Philadelphia in 1850.

He had not given up on being a physician, however, and after renewed effort, he was admitted to the American Medical College and graduated with a medical degree in 1852. He and his wife moved to Boston where Dr. Rock established a successful practice that offered free services to fugitive slaves.

A gifted orator, he lectured on behalf of the abolitionist cause, voting rights for free African Americans, and the newly-formed Republican Party. After poor health forced him to give up his medical practice in 1859 (by 1861, he had also given up dentistry), the undaunted Rock pursued a career in law. In 1861, he was one of the first African Americans admitted to the Massachusetts Bar; in September of that year, he was appointed a Justice of the Peace for Boston and Suffolk County, Massachusetts.

By then the country was at war, and throughout the conflict Rock was a tireless advocate for abolition of slavery. Like Frederick Douglass, he was an enthusiastic recruiter for the black volunteer regiments from Massachusetts. On February 1, 1865, the day after the House of Representatives passed the 13th Amendment to the Constitution, Senator Charles Sumner introduced a motion at the U.S. Supreme Court; when it passed that same day, John S. Rock became the first African American admitted to practice there. Rock's declining health prevented him from fully exercising this hallmark privilege. He died of tuberculosis in December 1866.

RUTH HARTLEY MOSLEY

Ruth Hartley Mosley was born as Ruth Price in Savannah in 1886. According to historians’ reports, she received an excellent education in Savannah. Her father was said to be a proud bootmaker who instilled a “legacy of independence and determination” into her.

She became a registered nurse while training in North Carolina and Chicago. When she returned to Georgia, she started working at the State Sanitarium in Milledgeville, later known as the Central State Hospital. There, she became the first black female to head a nursing department, the “Colored Females Department,” in 1910. She was only 24 years old.

She married Richard Hartley and become a licensed mortician with her husband in Macon, Georgia. They established the Central City Funeral Home Business. Following her husband's death in 1931, she continued to invest and build her fortune. Six years later, she married Fisher Mosley of New York City. In 1938, she began serving as a nurse with the Health Department and with Bibb County Schools.

Ruth Hartley Mosley rose to social prominence in Macon and when she spoke, people listened. Active in the NAACP, she was a founding board member of the Booker T. Washington Community Center. She owned extensive real estate. In her will, she left a trust to establish an education funds for nursing students, and the Ruth Harley Mosley Women’s Center. Today, the building at 626 Spring Street is a community-use facility. It’s also a location where her legacy continues as a place to encourage young girls to become nurses and community leaders.

Ruth Hartley Mosley died in 1975.

WILLIAM HUBBARD

Professor William Hubbard was born just after the Civil War in Wilkinson County. He attended Ballard Normal School in Macon and graduated from Ballard in 1891. He went on to attend Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee. Hubbard married Mollie Helena Worthy, a Ballard Normal graduate from Monroe County.

After he graduated from Fisk, he taught for four years in Cuthbert, Georgia. As an educated Black man, always focused on teaching opportunities and giving back to the community. Hubbard entered the teaching arena in Monroe County by a unique way.

As he attempted to support his family as a photographer, a minister at the Kynette Methodist Church allowed him to maintain his photography lab in the basement of the church. In exchange for having a place to work, Hubbard taught seven students at the minister’s request, thus beginning William Hubbard’s historic educational efforts in Monroe County.

With the help of both white and Black residents in Monroe County, Hubbard went only to establish the Forsyth Industrial School in December of 1902. In 1931, the name changed to the State Teachers and Agricultural College under the University System of Georgia. It became one of Georgia’s top institutions to educate Black teachers. After much debate, the school was merged with the Fort Valley State College in 1938. Hubbard served as Director of Public Relations at Fort Valley State, until he was hospitalized at Saint Luke Hospital in Macon.

Today, Samuel Hubbard Elementary School, named after William's son, educates students in Monroe County. The William Hubbard campus, where the original building once stood, is now a community park and museum of educational history. Decades of students have passed through the schools which also served a site of community unity.

February 6-12

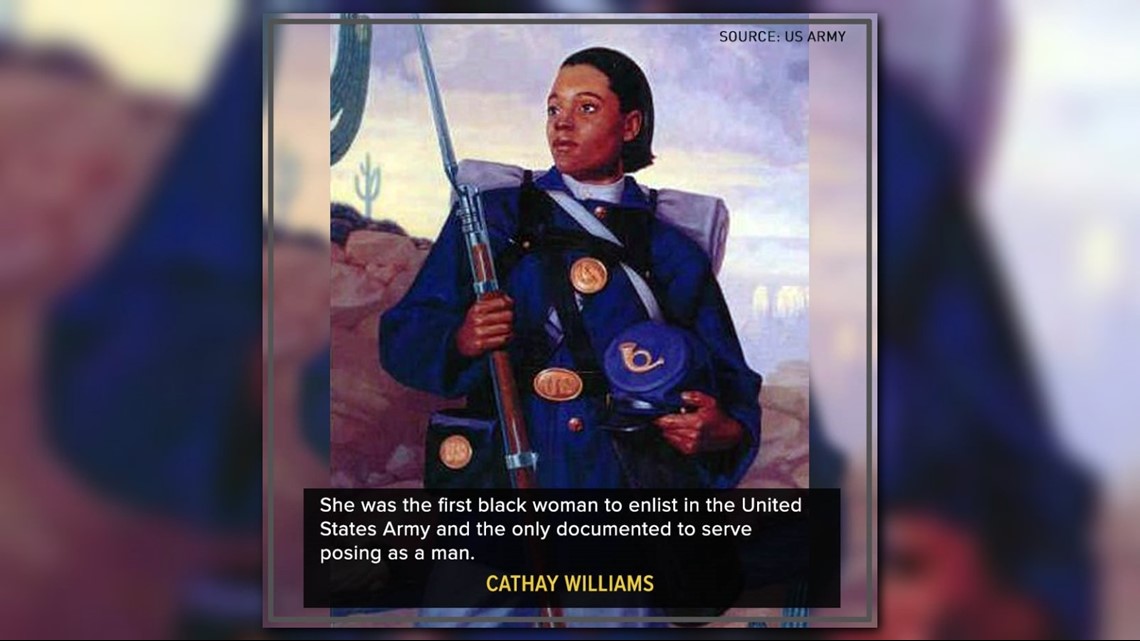

CATHAY WILLIAMS

Cathay Williams (September 1844 – 1893) was an African-American soldier who enlisted in the United States Army under the pseudonym William Cathay. She was the first Black woman to enlist, and the only documented to serve in the United States Army posing as a man.

Williams was born in Independence, Missouri, to a free man and a woman in slavery, making her legal status also that of a slave. During her adolescence, Williams worked as a house slave on the Johnson plantation on the outskirts of Jefferson City, Missouri. In 1861 Union forces occupied Jefferson City in the early stages of the Civil War. At that time, captured slaves were officially designated by the Union as "contraband," and many were forced to serve in military support roles such as cooks, laundresses, or nurses.

Despite the prohibition against women serving in the military, Cathay Williams enlisted in the United States Regular Army under the false name of "William Cathay" on November 15, 1866, at St. Louis, Missouri, for a three-year engagement, passing herself off as a man. She was assigned to the 38th United States Infantry Regiment after she passed a cursory medical examination. Only two others are known to have been privy to the deception, her cousin and a friend, both of whom were fellow soldiers in her regiment.

Shortly after her enlistment, Williams contracted smallpox, was hospitalized and rejoined her unit, which by then was posted in New Mexico. Possibly due to the effects of smallpox, the New Mexico heat, or the cumulative effects of years of marching, her body began to show signs of strain. She was frequently hospitalized. The post surgeon finally discovered she was a woman, and informed the post commander. She was discharged from the Army by her commanding officer, Captain Charles E. Clarke, on October 14, 1868.

(Info: US ARMY, US NATIONAL PARK SERVICE)

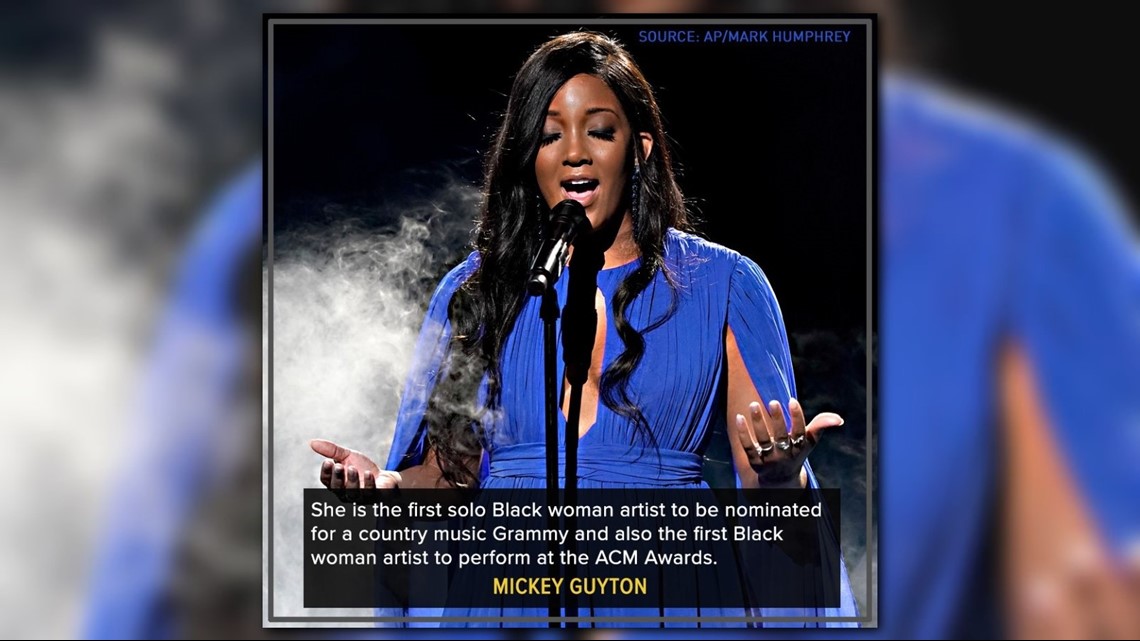

MICKEY GUYTON

Mickey Guyton (June 17, 1983 - ) is a country music artist who became the first solo Black woman artist to be nominated for a Grammy in a country category, and also the first Black woman artist to perform at the Academy of Country Music Awards.

Raised in Texas, Guyton was exposed to various types of music at a young age, and her material subsequently incorporates elements of contemporary country and R&B music. Moving to Nashville, Tennessee in 2011, she would later sign a recording contract with Capitol Records Nashville.

In 2015, Capitol released her debut single, titled "Better Than You Left Me." The song reached number 34 on the US Country Airplay chart and helped her receive a nomination from the Academy of Country Music Awards.

Guyton is known for breaking barriers with her hit song "Black Like Me," which bears the same name as John Howard's 1961 novel. The song is about her experiences navigating life and a career in country music as a Black woman. Guyton released the song in 2020 amid the spur of protests for Black Lives Matter that emerged across the nation after George Floyd's murder.

The singer made history at the Grammy Music Awards in 2021 after delivering a powerful performance of "Black Like Me," becoming the first solo Black woman artist to be nominated in a country category for the awards show. She later became the first Black woman artist to perform at the Academy of Country Music awards.

Guyton will be singing the national anthem at Super Bowl LVI at SoFi Stadium in Inglewood, California on Feb. 13 for the 2022 game.

(Info: AP, TEGNA)

PATRICK FRANCIS HEALY

Patrick Francis Healy was born in Macon, Georgia on February 27, 1834. Among his accomplishments, Healy is noted as the first Black American to become the president of a predominantly white university.

His mother was a former slave, and father was an Irish immigrant. Interracial marriage was prohibited by law in Georgia at that time. The Catholic Church did recognize interracial marriages, but there were no priests in the area, so the couple, Michael Morris Healy and Eliza formed a common-law marriage in 1829. Historians say they lived with each other faithfully for the rest of their lives until both died in 1850. Patrick Healy was one of 10 children born as slaves because of the law in Georgia. The eight children who survived held roles in the Catholic Church.

Healy’s parents sent him to the north for a better life, and he became a Catholic priest and Jesuit. Healy is most noted in history as the 29th president of Georgetown University from 1873 to 1882. Healy is recognized as the school's “second founder” because of his influence around the campus and Washington D.C. area. Historians say Healy worked to transform the institution into a modern university. During his time over the university, Healy is credited for increased the prominence of the sciences, raising the standards of the School of Medicine, expanding the Law School, and increasing the prominence of the sciences.

He is recognized as the first Black American to become a Jesuit, earn a Ph.D, and become the president of a predominantly White university. Because Healy’s biracial background was not widely known, he was able to move through life with little racial hostility. Although there was speculation about his racial background, Healy identified as white. However, knowledge of his mixed-race background was not a secret while he served as president of Georgetown University. Historians say Healy’s “fellow Jesuits knew of his mixed race,” but was not likely that they shared this knowledge outside of Jesuit circles.

Healy died January 10, 1910, in Georgetown.

EUGENE JACQUES BULLARD

Born in Columbus, Georgia on October 9, 1894, Corporal Eugene Jacques Bullard is credited with being the first Black American fighter pilot. A statue honoring him stands outside the Century of Flight hangar at Robins Air Force Base’s Museum of Aviation. During the war, his German enemies knew him as “the Black Swallow of Death.” He served in the two World Wars. Bullard flew in the French Air Service and served in other wartime positions. Liked and respected by his comrades, Bullard believed that through his deeds, people of African heritage might gain respect and equality in the US.

Bullard’s journey to France started in Georgia with parents who had French roots. He was the seventh of ten children born to William (Octave) Bullard, from the French Island of Martinique, and Josephine or Yokalee Thomas, a Native American. Eugene’s father’s family came from Martinique, an Island in the West Indies and spoke French fluently. They arrived in America as slaves when their French owners fled the Haitian revolution. His mother died when he was only 5, and Bullard’s father raised him.

In 1902, at the age of 8, Bullard fled Columbus after witnessing a mob nearly lynch his father. He knew his French roots and set out to make enough money to go to France. Through his many jobs as a preteen, he was able to save enough money to reach Norfolk, Virginia, and at the age of 12, stowed away on a German ship bound for Aberdeen, Scotland. At age 16, he began a successful career as a boxer. That skill allowed him to travel to Paris. Not only did he box, but also acted as an interpreter for the non-French speaking.

Europe had fallen deeper into war by 1914, and an underage Bullard joined the French Foreign Legion at 16. Bullard survived some of the worst battles of the war between 1914 and 1916. On 5 March 1916, Bullard was severely wounded. Even so, he recovered and later, was awarded the Croix de Guerre and Medaile Militaire.

Bullard’s injuries may have kept him out of the infantry, but fame from an interview by Will Irwin of The Saturday Evening Post opened the chance to join the French Flying Corps. Also, an American friend of Bullard’s bet him $2,000 that he could not become a pilot. Historians point proof that Bullard won the bet and was paid the money.

When the United States joined the war, Bullard wanted to transfer. He had been a pilot for three years. After passing the physical, he expected to receive an assignment in the Air Force. Instead, his application was ignored since white pilots refused to fly with him for the duration of the war. He went on the marry, have three children, and even start a successful nightclub in France. When war began to threaten France in July 1940, Bullard joined the French resistance movement. Because Bullard could speak three languages including German, he also served as a spy for France.

On 12 October 1961, after suffering a long illness, Eugene Jacques Bullard died. The French never forgot his service and honored him through the years. It was not until the 1960s that the American government recognized his heroism. On 23 August 1994, 77 years after Bullard’s American flight physical and application denial, he was officially honored. To pay homage to African American heroes wrongly ignored, President Bill Clinton posthumously commissioned Eugene Jacques Bullard a Second Lieutenant.

OZZIE BELLE McKAY

Historians note Ozzie Belle McKay’s dedication to community service and Macon’s Civil Rights movement. Thousands of young women and men gained leadership and social skills from McKay’s training. Historians see McKay as an organizer and “foot soldier” of the movement, but she was among the leaders who tried to avoid the limelight while working hard to make the community a better place. Her talents and hard work might have been missed by Macon if it was not for a childhood tragedy that brought her to the Pleasant Hill community.

Ozzie Belle McKay was born June 15, 1906 in Quitman, Georgia. She was 5 years old when her parents passed. McKay was sent to live with her uncle, aunt, and cousin in the then-segregated community of Pleasant Hill in Macon, Georgia. McKay’s aunt was the noted Cleopatra Love, an educator who focused on learning and teaching Black history. McKay said she enjoyed living in the nurturing community of Pleasant Hill, which got its name from “the cool evening breeze enjoyed long before air conditioning.” One of the things she says she took from her life in Pleasant Hill was realizing the community was a “microcosm of America.” There in Pleasant Hill was the economic, political, educational, and social strengths that held the area together in harmony.

Motivated by what she grew up around, Ozzie Belle McKay valued education and set out to give back to her community. She says she recognized her “ancestral obligations to serve and to give something back to the community” that gave her so much. She was especially interested in helping the community's children.

After McKay graduated valedictorian from Beda-Etta College in 1925, she went on to become one of the area’s most successful insurance agents with Atlanta Life Insurance. Beda Etta College was a business-focused school located in Pleasant Hill and founded by Minnie Lee Smith in 1921. McKay never learn to drive, so she did not have a car, but when she retired from Atlanta Life Insurance, it is reported that the company had to hire two agents to take her place.

Her influence was well-known, and she had an impact on local leaders of yesterday and present day. Politicians would often ask McKay for help getting elected because of her extensive list of contacts developed from her door-to-door work as an insurance agent. The late Dr. Lonzy Edwards, a Macon pastor, attorney, and former Bibb County commissioner, is quoted as saying, “No one in his right mind would ever enter a political battle without making sure Miss Ozzie is on your side.”

McKay’s work with children began with her annual doll parties. It was done to give children positive images of themselves and build their self-esteem. Over her decades of dedication to young women and men, she founded of the Ozzie Belle McKay Federated Girls Club and the Lewis B. Sheftall Boys Club. Thousands of people past through her social and civic training under the organizations and went on to hold various successful positions.

McKay was the treasurer of the Macon Chapter of the NAACP for more than 30 years. She served on the boards of the Booker T. Washington Center and the Ruth Hartley Mosley Women’s Center. She also organized the Neighborhood Watch Club in her Pleasant Hill community.

She received many awards during her lifetime. Former Governor Joe Frank Harris named her Lt. Colonel of Georgia. She was given the President Award for her role in the Democratic Women of Bibb County. She was selected as a Woman of Achievement by the Georgia Career Women’s Network and honored by her founding club members over the years. Among the last large gatherings of women celebrating Ozzie Belle McKay happened in 1997. The then-88-year-old McKay was celebrated by some thousands of young women she taught community leadership skills to under the Federated Girls Club.

Ozzie Belle McKay died on October 14, 2004, at the age of 95.

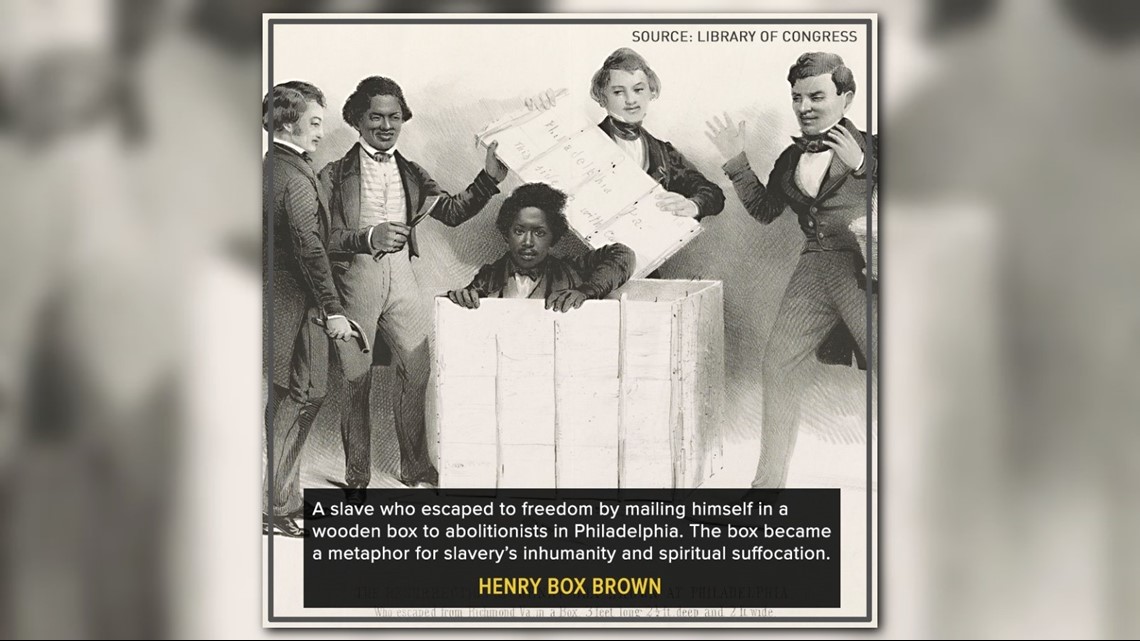

HENRY BOX BROWN

Born into slavery in Louisa County, Virginia, Henry Brown (1815 or 1816-June 15, 1897) became a skilled worker in a Richmond tobacco factory. About 1836 he married Nancy, an enslaved woman owned by another master, and the couple had at least three children. Brown was able through overwork to rent a house for his family. In August 1848 Nancy Brown's owner suddenly sold her and the children out of the state. With nothing to keep him in Richmond, Brown resolved to escape to freedom. Working with a free black dentist and a white shoemaker, he concocted a scheme to ship himself north. On March 23, 1849, his co-conspirators sealed Brown into a wooden crate and placed it on a train bound for Philadelphia. After 26 hours, Brown arrived at the office of the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society, where he was unboxed, alive and free.

As Henry Box Brown, he began an active career lecturing and performing. He worked with the artist Josiah Wolcott and others to create a moving panorama to illustrate his lectures about slavery. Henry Box Brown's Mirror of Slavery opened in Boston on April 11, 1850. During the lecture, Brown would climb into a replica of the box and re-create his unboxing. By October 1850, after an abortive kidnapping attempt and fearful that he would be arrested and returned to Virginia under the new federal Fugitive Slave Act, Brown sailed for England, where he remained for more than a decade.

In his performances in England and Wales, Brown mingled his antislavery lecture and panorama with entertaining acts. In 1875 he returned to the United States with a wife, whom he had married by 1859, and a daughter. The Browns performed at Milbury and Worcester, Massachusetts, at the beginning of 1878, and an Ontario newspaper reports a performance of the Brown Family Jubilee Singers at Brantford on February 26, 1889. By that time Henry Box Brown was living in Toronto, where he died on June 15, 1897. He was buried in Necropolis Cemetery there.

(Info: LIBRARY OF VIRGINIA)

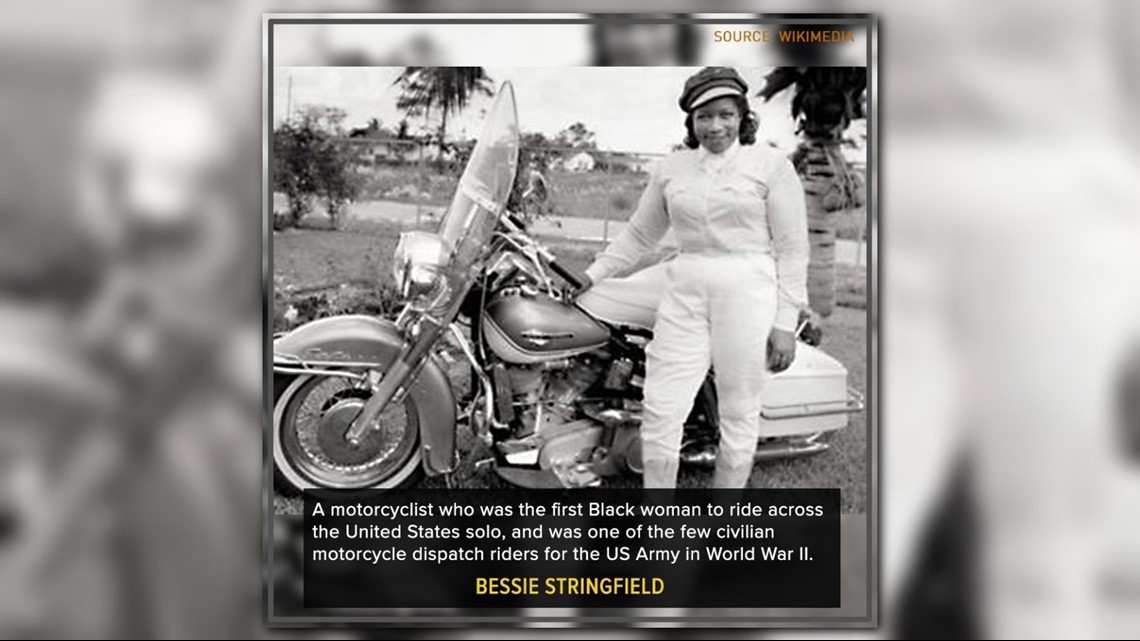

BESSIE STRINGFIELD

Bessie Stringfield (1911 or 1912 – February 16, 1993) was a motorcyclist who was the first African-American woman to ride across the United States solo, and was one of the few civilian motorcycle dispatch riders for the US Army during World War II. Credited with breaking down barriers for both women and Jamaican-American motorcyclists, Stringfield was inducted into the Motorcycle Hall of Fame. The award bestowed by the American Motorcyclist Association (AMA) for "Superior Achievement by a Female Motorcyclist" is named in her honor.

During World War II Stringfield served as a civilian courier for the US Army, carrying documents between domestic army bases. She completed the rigorous training and rode her own blue 61 cubic inch Harley-Davidson. During the four years she worked for the Army, she crossed the United States eight times. She regularly encountered racism during this time, reportedly being deliberately knocked down by a white male in a pickup truck while traveling in the South.

In the 1950s, she qualified as a nurse in Miami and founded the Iron Horse Motorcycle Club. Her skill and antics at motorcycle shows gained the attention of the local press, leading to the nickname of "The Negro Motorcycle Queen." This nickname later changed to "The Motorcycle Queen of Miami," a moniker she carried for the remainder of her life.

Stringfield died in 1993 from a heart condition, having kept riding right up until the time of her death.

February 13-19

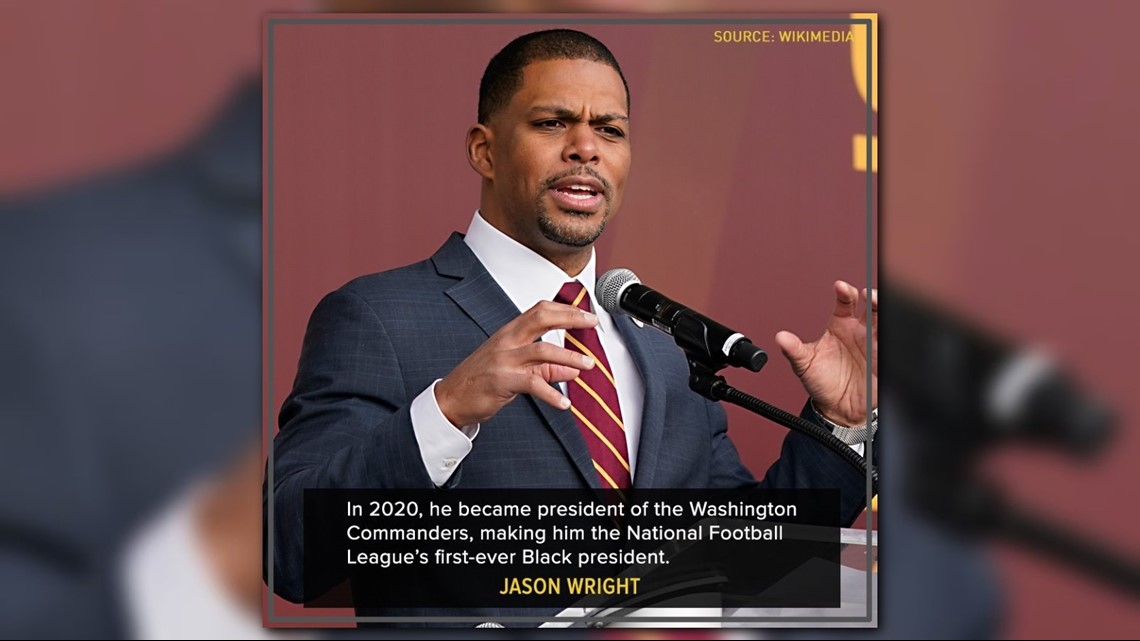

JASON WRIGHT

Jason Gomillion Wright (born July 12, 1982) is a businessman who is the president of the Washington Commanders of the National Football League (NFL). A native of the Greater Los Angeles area, he attended Northwestern University and played running back for their football team. He went on to play seven years in the NFL as a backup running back, originally signing with the San Francisco 49ers in 2004 as an undrafted free agent before having stints with the Atlanta Falcons, Cleveland Browns, and Arizona Cardinals. With Arizona, he served as a team captain and was their NFLPA representative during the 2011 NFL lockout before retiring that same year.

Following his playing career, he enrolled at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business and graduated with a Master of Business Administration degree in operations and finance in 2013. He then worked for the management consulting firm McKinsey & Company, where he advised companies on organizational culture and workplace diversity. He left McKinsey in 2020 to become president of the NFL's Washington Commanders, making him the first black person in league history to have that title.

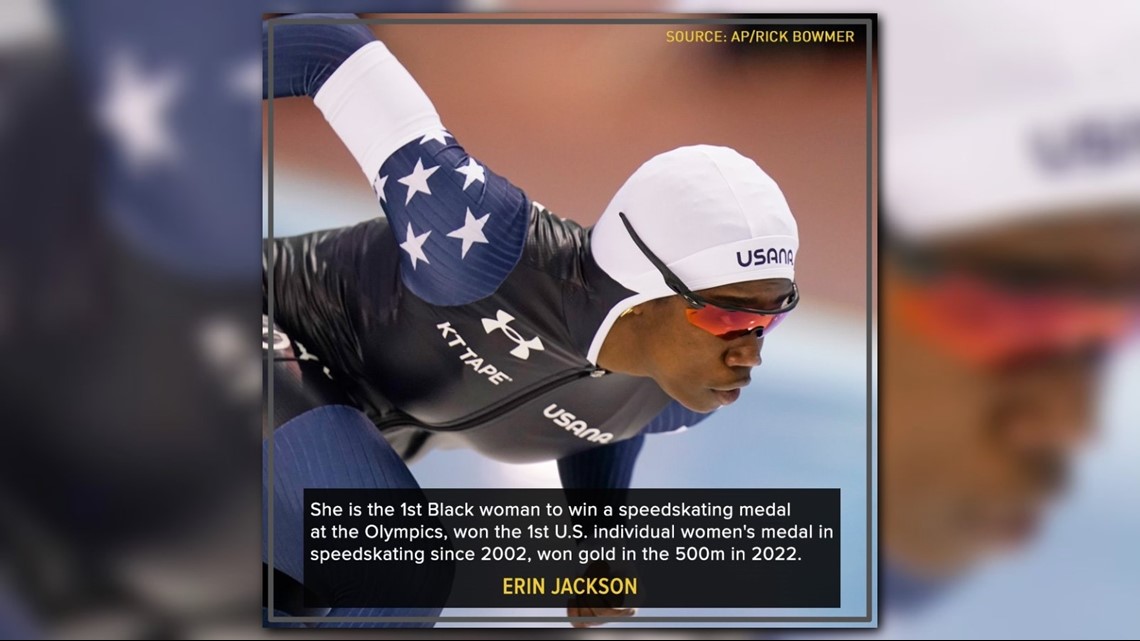

ERIN JACKSON

Erin Jackson made history at the 2022 Winter Olympics on Sunday, putting in a sensational race in the women's 500-meter speedskating final.

She accomplished several historic feats with her performance in Beijing.

Jackson became the first Black woman to win a speedskating medal at the Olympics, won the first U.S. individual women's medal in a speedskating event since 2002 and achieved something that has eluded American women since the legendary Bonnie Blair last did it in 1994: Win gold in the 500m.

Jackson's time of 37.04s edged out Japan's Miho Takagi by 0.08 seconds.

Jackson's rise to Olympic glory is a remarkable one. In 2018 she became the first Black woman to qualify for Team USA in long-track speedskating, after only four months of experience on ice following a competitive career in inline skating.

The Florida native came into the Winter Olympics following a hot start to the 2021-22 World Cup season that saw her on top of the 500-meter standings with five wins in eight races. That left her coming into the Games as the No. 1 ranked speed skater in the world by the International Skating Union.

She now joins Blair, one of the greatest speed skaters in U.S. history. Blair won gold medals in the 500m at three straight Olympics - Calgary 1988, Albertville 1992 and Lillehammer 1994. Blair also twice won a gold medal in the 1,000-meter event, as well.

(Info: TEGNA)

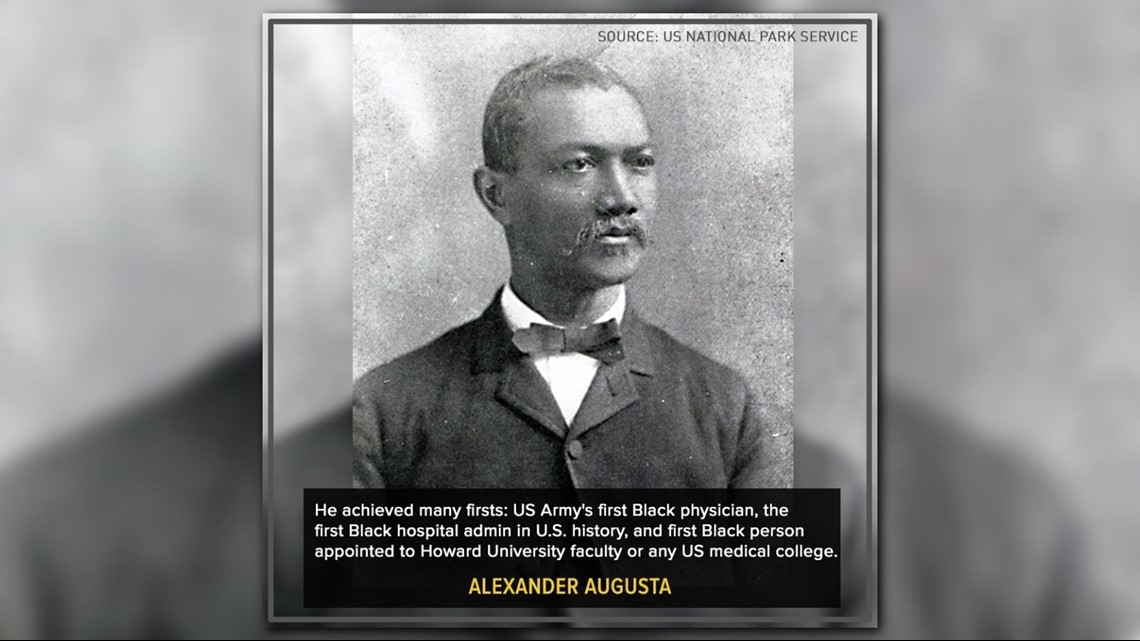

ALEXANDER AUGUSTA

Dr. Alexander Thomas Augusta was a pioneer for Blacks in the 19th Century, paving the way for millions who would follow. He consistently rose above the bigotry of his time, continually fighting for the rights of other Blacks, and himself. He lived a successful and full life, despite the myriad of obstacles he faced throughout.

Alexander Thomas Augusta was born to free parents of color in Norfolk, Virginia on March 9, 1825. From his very first memories, he wanted to become a doctor. He spent his early years working towards that goal, something that was not easy for a Black man in the 19th Century. Despite state laws prohibiting the education of Blacks, Augusta learned to read and write.

As a young adult he moved to Baltimore, and then to Philadelphia, where he hoped to enroll into the University of Pennsylvania’s medical school. Throughout these transitions, he supported himself by working as a barber. Augusta was denied entrance to the university due to what he called a “prejudice of color.” Because of laws preventing the education of Blacks, he would have lacked the evidence needed to prove that he had the prerequisites for admittance. This was likely another factor for his rejection. Undaunted, Augusta was able to convince a professor who was sympathetic to his cause, to secretly tutor him.

Eventually, he moved to Toronto, and Augusta was not only running his business, he was also working towards his medical degree. He had been accepted into Trinity College where he graduated with a bachelor of medicine degree in 1856. The president of the college said that Augusta was one of his most “brilliant students.” He established his own successful practice that included patients of all colors and incomes. Augusta was later appointed as the head of the Toronto City Hospital.

Despite his deepening roots in Canada, Augusta kept one eye on his home country as it moved into a Civil War. Augusta was stirred into action when the Emancipation Proclamation was signed by President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863. This historic document called for the freedom of enslaved people in the Confederate states. It also allowed for the recruitment of Blacks to the Union Army. Augusta believed that “the coloured people have a duty to perform at this present time” so he wrote to President Lincoln and Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, on January 7, to offer his services to one of the Black regiments in the Union army. He requested “an appointment as surgeon to some of the coloured regiments, or as a physician to some of the depots of freedman.”

Alexander wanted to help the Union army while also supporting black soldiers. He knew that he could serve as an example of what was possible for an educated Black man placed in a position of authority. Upon receiving a confirmed appointment for a military examination, Augusta left Canada, the country that had given them so many opportunities, never to return again.

However, trouble commenced upon his return to the United States. Two days before his exam with the U.S. Surgeon General, Augusta received a letter claiming that there had been a mistake. His invitation to join the army was being “recalled” due to the fact that Augusta was a “person of colour.” The letter also stated that his military service would violate Great Britain’s proclamation of neutrality; that his ten years spent living in British North America technically made him a British subject.

Alexander fought back and again wrote to President Lincoln, and members of the army’s medical board: “I have come nearly a thousand miles at great expense and sacrifice, hoping to be of some use to the country and to my race at this eventful period.” He mentioned that the rate of death from illness and disease among black servicemen was nearly twice as high as their white counterparts, thus the need for more medical staff in the field. On April 1, the Medical Board changed its stance and recommended that he be appointed as a surgeon for one of the black regiments. On April 14, 1863, at age 38, Augusta was commissioned as a surgeon with the rank of Major in the Union Army with the 7th U.S. Colored Infantry. He was the first of eight Black doctors to hold a commission in the Union Army.

Augusta’s lifelong efforts ultimately earned him the attention and respect of the military leadership. At the close of the war, he was awarded an honorary brevet rank of lieutenant colonel. This prestigious distinction made Augusta the highest-ranking Black officer in the U.S. Military, at that time.

In 1869, he was hired by the newly formed Medical College at Howard University, becoming the first black medical professor in the country. Some of his subject areas included "Practical Anatomy," "Descriptive and Surgical Anatomy," and “Diseases of the Skin."

Augusta embodied the rapid change in the country during the Civil War and Reconstruction Era. A mere 20 years before he became the first African American to teach medical science at the college level, he was denied access to an education.

When Augusta was denied membership to the Medical Association of the District of Columbia, he helped create the National Medical Society. The NMS opened membership to all physicians, regardless of race, and still operates today under the same founding principles.

Alexander T. Augusta died in 1890, at the age of 65 in Washington, DC. To close out an incredible life of accomplishments and “firsts”, he was the first black officer-rank soldier to be buried in the Arlington National Cemetery. He is laid to rest in section one, in a location that, for reasons unknown and perhaps entirely coincidental, is set apart from the graves of White soldiers.

(Info: NATIONAL PARK SERVICE)

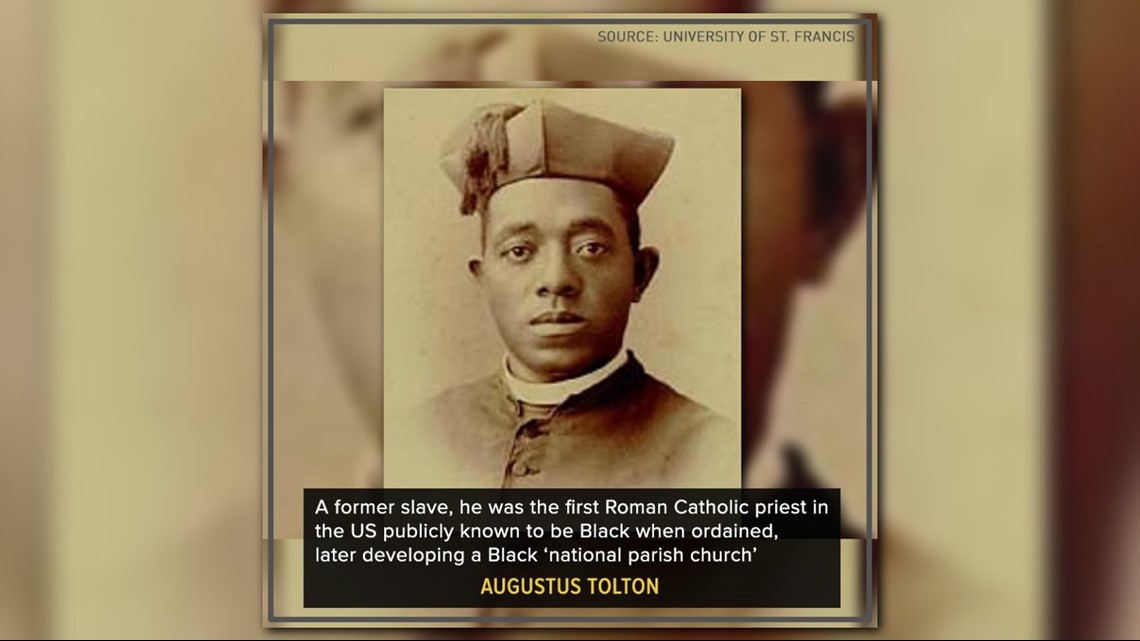

AUGUSTUS TOLTON

Fr. Augustus Tolton, the first black Catholic priest to be ordained in the United States, lived from 1854 to 1897. His parents were both slaves. He and his family eventually gained freedom in Illinois, where he was moved by the calling to become a priest. It was the Franciscans who welcomed him into St. Francis College (now Quincy University) in Quincy, Illinois, to begin his higher education when no seminary or religious order in the U.S. would accept him because of his race. With their help, he was finally able to go to Rome to study for the priesthood and was ordained in 1886.

Tolton, who has long been recognized by the USF community as an inspirational figure—perhaps because of his strong connection to the Franciscans—moved deeper into the public eye in 2010 when Cardinal Francis George in Chicago announced a cause for Tolton’s canonization. As Fr. Tolton’s story was shared, the university also pulled him nearer in different ways.

In 2012, USF’s African American honor society was officially named the ”Augustus Tolton Honor Society.” The society honors the spirit of scholarship, leadership, and identity for high-achieving African American students at USF and nurtures intellectual ability, promotes leadership development, fosters knowledge of self, and provides service to the community while upholding the university’s values of respect, compassion, service and integrity.

(Info: University of St. Francis)

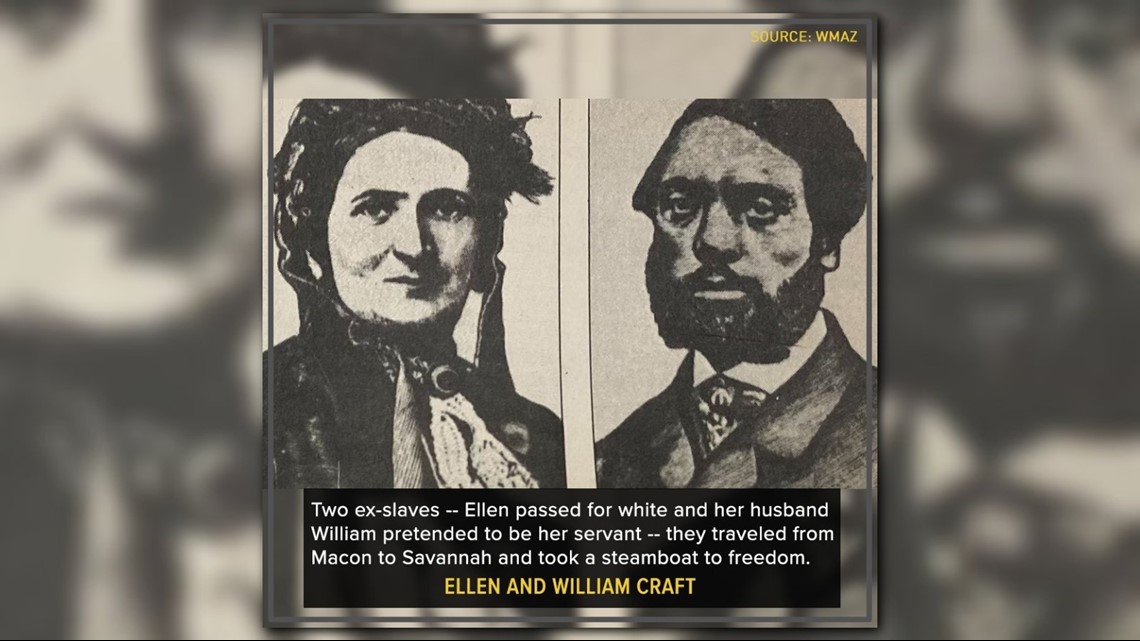

ELLEN AND WILLIAM CRAFT

Macon is rich with Black history, but these two figures have transcended to national history.

Ellen and William Craft were two former slaves who made a daring escape to the North during the mid-1800s. Their story begins with Ellen working and living with her half-sister, Eliza Smith Collins, and her husband.

During her time with Eliza, Ellen met former slave William Craft. After falling in love and marrying, the Crafts decided to plan their escape from slavery.

Tubman Museum's director of exhibitions, Jeff Bruce, says, "What they decided to do was to dress Ellen as a young white planter."

With Ellen being biracial because her father was her former owner, she was light-skinned and therefore white-passing. Her disguise in order to pass as a white man was meticulous.

“They cut her hair short, they wrapped her head in a handkerchief to hide the fact that she didn’t have facial hair. They put her arm in a sling -- that was to make it impossible for her to sign any documents because neither one of them could read or write,” said Bruce.

In Dec. 1848, four days before Christmas, they made their escape. Their route included taking a steamer and train before reaching Philadelphia on Christmas Day.

Despite the Crafts reaching the North where slavery was banned, they still weren’t safe from persecution as slave catchers were sent after them a few years later.

The Crafts later relocated to England for 19 years before returning to the South after amendments granted emancipation passed.

“They have become symbols of bravery, optimism and overcoming obstacles," said Bruce.

CYNT MARSHALL

Cynthia Marshall is the chief executive officer of the Dallas Mavericks basketball team. In February 2018, Marshall became the first black female CEO in the history of the National Basketball Association. Marshall was also one of her university's first African-American cheerleaders at the University of California, Berkeley in the late 1970s. Marshall worked for AT&T for 36 years in leadership role focused on improving workplace culture and encouraging diversity and inclusion.

Marshall moved from Birmingham, Alabama to California when she was three months old. Marshall was raised in Richmond, California with three siblings. She describes her childhood as being painful growing up in public housing projects with a family struggling to pay the bills. When she was 11 years old, Cynt witnessed her father shoot a man in the head in self-defense. In 1975, when Marshall was 15, her father broke her nose as she set out to save her mother from his domestic abuse. Her mother, Carolyn Gardener, was a high school executive administrator and resource librarian.

Marshall prefers to be called "Cynt" as she acquired the nickname with her high school track team — "Cynt the Sprint."

Marshall received a full scholarship to attend the University of California, Berkeley to study business administration and human resources management. While studying at Berkeley, Marshall became the university's first black cheerleader. After graduating from university at 21, she took on a job as a supervisor at AT&T.

Marshall worked in executive roles at AT&T for 36 years, where she focused on improving diversity and workplace behavior. She retired in 2017, and founded the consulting firm Managing Resources.

In 2018, Dallas Mavericks owner Mark Cuban hired Marshall following allegations claiming 20 years of sexual harassment and workplace misconduct within the Mavericks organization.

THE PEOPLE OF JODY TOWN

Part of the rich diversity making up the early development of Warner Robins was the establishment of an African American community known as Jody Town.

Possibly named after the African American blues character, it was home to Black individuals hired to work in various areas of construction at the Army Air Depot, known today as Robins Air Force Base. There was a strong connection between Robins AFB and the neighborhood, which the base says grew between 1941 and 1943. Historians say from Jody Town grew neighborhoods, organizations, and many Black-owned businesses helping to make up Warner Robins.

The military selected the quiet town of Wellston to build the Army Air Depot. News of the job opportunities spread, and people moved to the area looking for work. With the declaration of war on Japan in 1941, the pace of construction increased, and more workers were needed.

This opened the door for many people, including African Americans, to move to the little town for work. African Americans from across the Southeast, including those eager to trade off sharecropping for civil service and contracted work, came to Wellston. Local Landowners developed their properties to build housing for military members and their families. Separate housing was developed for Black families.

Historians say Mary and Loyd Perdue and Fred W. Carter developed the Plantview Subdivision. Military families who lived there are said to call the area Jody Town.

Between 1941 and 1943, more than 100 lots were built. According to Robins Air Force Base, “The street names of Amanda and Leroy were named after Carter children, and Garman and Simon Streets were named for the first neighborhood residents, who were African-American. Other neighborhood streets were Washington, First (now Armed Forces Blvd), Second and Third.”

The Base says from the beginning, there was a strong link between the neighborhood and Robins AFB. “Military members often boarded in neighborhood homes, and many of the African-American workers constructing the depot took their meals or lodged with Jody Town residents,” according to base records. The location of Jody Town was convenient because it was a short walk to the depot’s main gate.

As the neighborhood grew, historians say the residents thrived. They say many Black-owned businesses expanded and included a brick masonry that trained men for positions with Air Force contractors. They founded churches, established Girl Scout Troop 333, and Boy Scout Troop 163. This was the first Boy Scout troop in Warner Robins.

“The Warner Robins Adult School for Colored was founded to help adults earn GED diplomas and learn technical skills that would allow them to qualify for civil service jobs at Robins AFB,” according to the base. This school was active through the 1970s. As for entertainment, famous performers like Little Richard Penniman and Otis Redding performed at the noted House of Soul nightclub.

Before Warner Robins had its own recreation department, Jody Town was where the Warner Robins Jets, a baseball team, was founded in 1964. The team served as a semiprofessional baseball league in the town. Members of that early team came together in 2021 for a reunion of former residents and descendants of Jody Town. Because the Warner Robins Jets called Memorial Park home, the city decided to invest in Memorial Park and found other teams. Historians say, “The Park became a hub for recreation and integration through the 1960s and 1970s.”

In June 2021, The Georgia Historical Society placed a marker in Memorial Park highlighting the legacy and contributions of the Jody Town Community. The marker also honors the Warner Robins Jets.

February 20-28

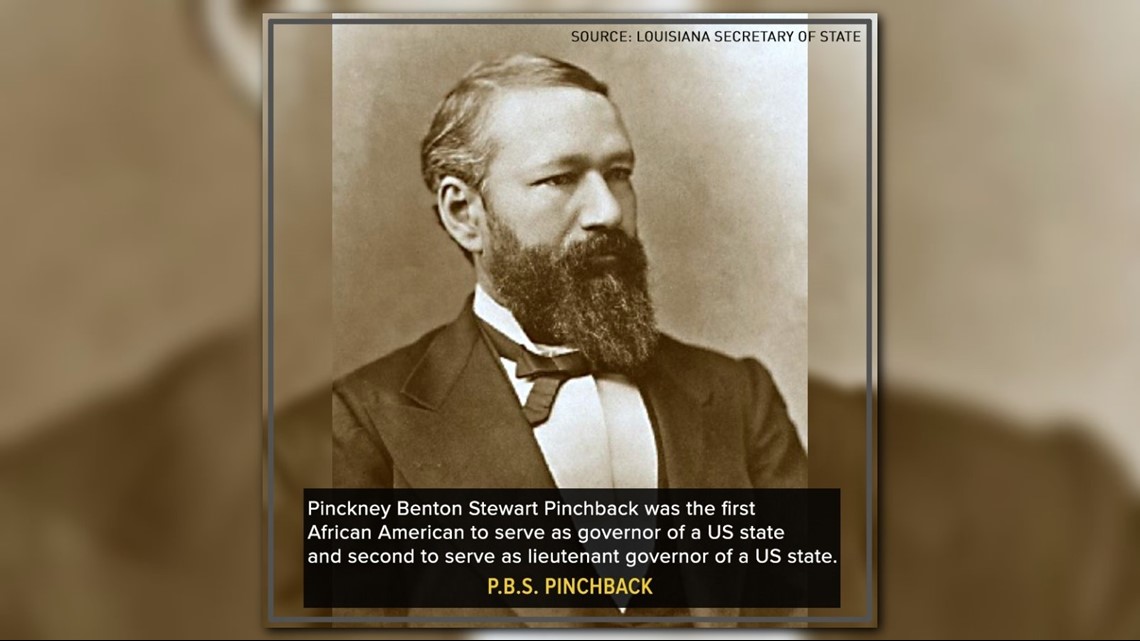

P.B.S. PINCHBACK

Pinckney Benton Stewart Pinchback was the first African American to serve as governor of a U.S. state and the second African American (after Oscar Dunn) to serve as lieutenant governor of a U.S. state. A Republican, Pinchback served as acting governor of Louisiana from December 9, 1872, to January 13, 1873. He was one of the most prominent African-American officeholders during the Reconstruction Era.

Pinchback was born free in Macon, Georgia, the son of a white Mississippi planter and a freed slave. He became active in Republican Party politics in Louisiana as a delegate in the Republican state convention of 1867 and to the Constitutional Convention of 1868.

Pinchback became Lieutenant Governor under Henry Clay Warmoth when Oscar Dunn died. After Warmoth was impeached, Pinchback became Governor. He held office for only 35 days, but ten acts of the Legislature became law during that time.

After William Pitt Kellogg took office as a result of the controversial election of 1872, Pinchback continued his career, holding various offices including a seat on the State Board of Education, Internal Revenue agent and as a member of the Board of Trustees of Southern University.

Pinchback helped establish Southern University when, in the Constitutional Convention of 1879, he pushed for the creation of a college for Blacks in Louisiana.

Pinchback and his family moved to Washington and then New York where he was a Federal Marshal. He later moved back to Washington to practice law and died there in 1921.

Pinchback is buried in Metairie, Louisiana.

(Info: LOUISIANA SECRETARY OF STATE)

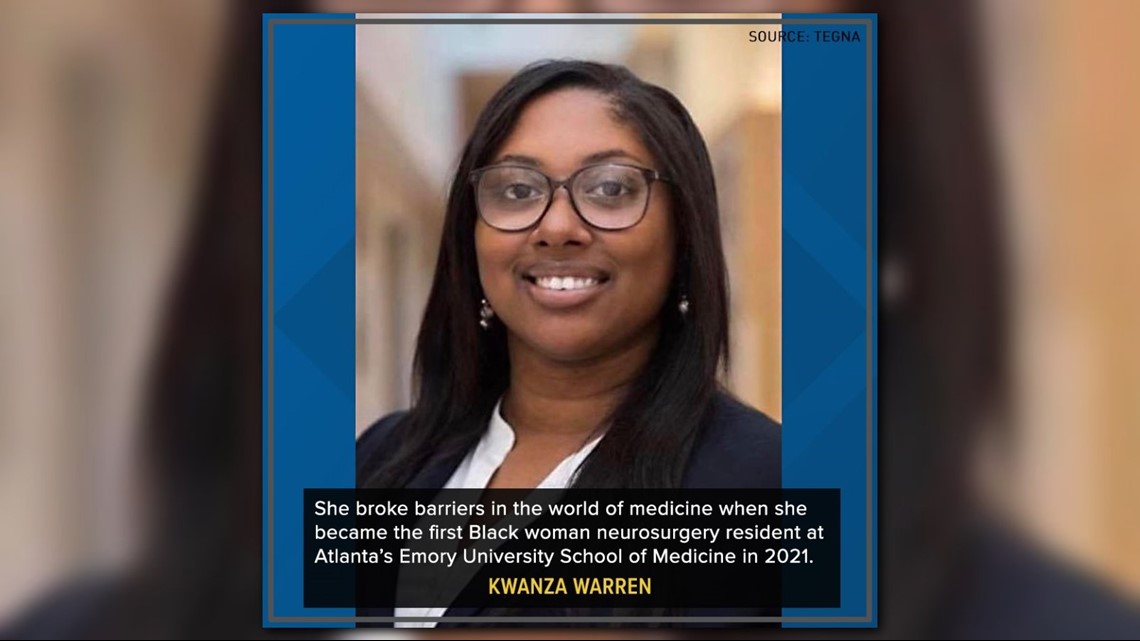

KWANZA WARREN

Kwanza Warren broke barriers in the world of medicine when she became the first Black woman neurosurgery resident at Emory University School of Medicine in 2021.

Warren, who is now in her second year of residency at Emory remembers the moment she found out she had made history.

"I realized I was the first African American female resident at Emory after the match when Dr. Nduom posted about it on Twitter," she said. "It's a little nerve-wracking at times because I sometimes feel as though I'm representing a whole group in a space that has no experience with someone like me in this capacity.

Warren graduated from the University of Rochester School of Medicine in 2020. Soon after she moved to Atlanta to start her residency.

She has succeeded in what is a traditionally male-dominated field. According to The U.S. National Library of Medicine, only 12% of neurosurgeons are women and 4% are Black.

Warren told 11Alive that her passion for neurosurgery started when she heard her brother wanted to become one.

"He came home from school that day and said that he wanted to be a neurosurgeon and I had no idea what that was. I was probably in first grade at the time and said, 'Oh, I'll be a neurosurgeon, too,'" she said.

Soon after she developed a love for neuroscience. When it came down to picking a path, Warren said it was difficult to choose between the two things she loved the most.

"I was between neurology and neurosurgery because I knew I wanted to do something in the neurosciences and fell in love with surgery and medical school," said Warren.

To make it through this challenging field, Warren said she often reflects on her dad’s encouragement.

"Whenever I started going through college and having, you know, rough days and rough times where I felt like I was working really hard and maybe wasn't getting as much out of it as I thought I could - my dad's was always like, 'You know, you're a Warren, so you're going to be fine,'" she said.

Warren hopes that her presence in this field opens the doors for others.

"Hopefully being in this field will allow others of similar background to consider neurosurgery who might not have otherwise done so," she said.

(Info: TEGNA/WXIA)

MINNIE LEE SMITH

Minnie Lee Smith was a Macon educator driven by the goal of making sure African American children had an educational future beyond elementary school. She is noted as a pioneer of education in Macon. Smith recognized that young Maconites had limited options without secondary education. Through fundraising efforts and money from her own pockets, Minnie Lee Smith founded Beda-Etta College in Pleasant Hill in 1921. Before the college, there were no high schools for Black students in Macon.

Smith was born around the late 1890s. Her parents were Dr. L.H. Smith and Mrs. Hester Love Smith. She had two sisters, Lovia and Roberta. Part of her educational career began as a teacher at Green Street School, a public elementary school for Black children in Macon.

Smith saved her money, conducted fundraisers, and through a yearlong effort, was able to build Beda-Etta College. The three-story brick building was located on Grant Avenue in the Pleasant Hill neighborhood. It served as a two-year college and a high school. The school was named after the nicknames Smith had for her two of her sisters, Roberta, or “Beda,” and Lovia, or “Etta.” Beda-Etta College offered courses in the general high school curriculum, as well as business and teacher training. Beda-Etta College operated for 34 years. The doors closed in 1955.

Today, a stone portion of Beda-Etta College has been preserved and is on display at the Tubman Museum in downtown Macon.

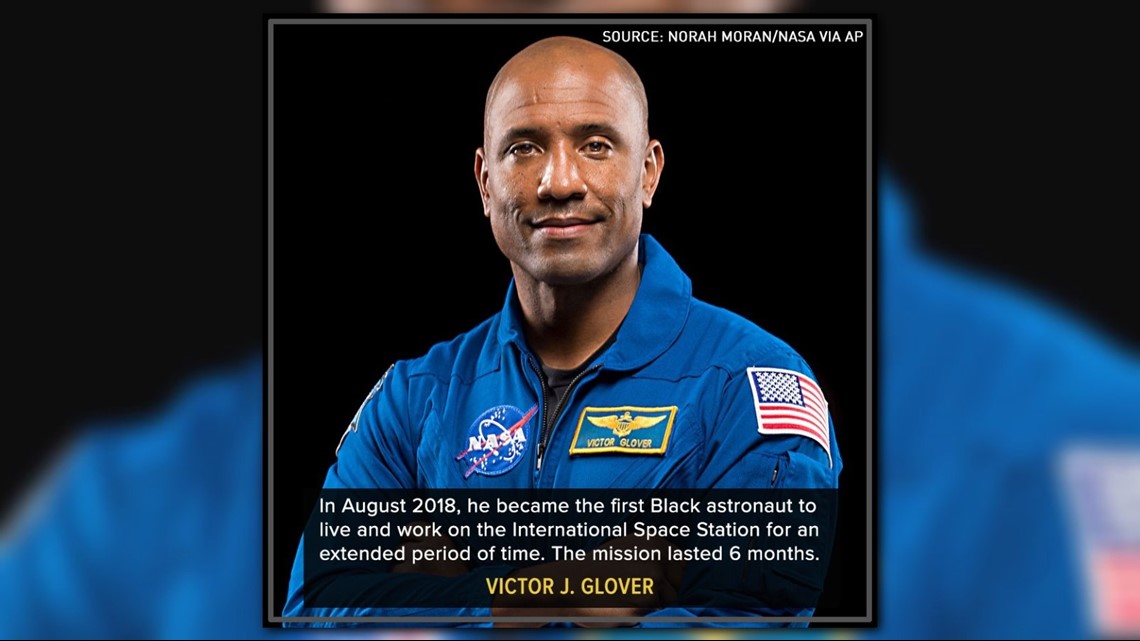

VICTOR J. GLOVER JR.

Victor J. Glover, Jr. was the first Black astronaut to live and work on the International Space Station for an extended period of time. Of the 300+ NASA astronauts who have been sent to space, only 14 have been Black Americans.

Glover was selected as an astronaut in 2013 while serving as a Legislative Fellow in the United States Senate. He most recently served as pilot and second-in-command on the Crew-1 SpaceX Crew Dragon, named Resilience, which landed May 2, 2021. It is the first post-certification mission of SpaceX’s Crew Dragon spacecraft – the second crewed flight for that vehicle – and a long duration mission aboard the International Space Station. He also served as Flight Engineer on the International Space Station for Expedition 64.

The California native holds a Bachelor of Science in General Engineering, a Master of Science in Flight Test Engineering, a Master of Science in Systems Engineering and a Master of Military Operational Art and Science. Glover is a Naval Aviator and was a test pilot in the F/A‐18 Hornet, Super Hornet and EA‐18G Growler. He and his family have been stationed in many locations in the United States and Japan and he has deployed in combat and peacetime.

Glover was selected in 2013 as one of eight members of the 21st NASA astronaut class. In 2015, he completed Astronaut Candidate Training, including scientific and technical briefings, intensive instruction in International Space Station systems, spacewalks, robotics, physiological training, T-38 flight training and water and wilderness survival training.

SpaceX Crew-1 and Expedition 64 (November 15, 2020 to May 2, 2021) was the first post-certification mission of SpaceX’s Crew Dragon spacecraft – the second crewed flight for that vehicle – and a long duration mission aboard the International Space Station. He also served as Flight Engineer on the International Space Station for Expedition 64. He contributed to many things while aboard the station including scientific investigations, technology demonstrations, growing crops and taking hundreds of pictures of Earth. He completed 168 days in orbit and participated in four spacewalks.

(Info: NASA)

CLARA BELLE DRISDALE WILLIAMS

Clara Belle Drisdale Williams made history in 1937 when she became the first African American to graduate from the New Mexico College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts (now NMSU). She was born on October 29, 1885, in Plum, Texas to Isaac and Malinda Drisdale. While growing up, Clara remembered her parents, sharecroppers who taught themselves to read and write, stressing the importance of education. In an interview with a Chicago newspaper, she recalled that her grandfather would bounce her up and down on his lap saying “This is going to be my little school teacher.” Clara’s parents wanted their children educated at any cost. It is evident that Clara took her family’s advice in pursuing her education, although it was not an easy path due to racial segregation and discrimination.

Clara was educated in a one-room schoolhouse near her family residence in rural Texas. In 1901, Clara obtained a four-year scholarship to the Prairie View Normal and Industrial College in Prairie View, Texas (now Prairie View A&M University) where she obtained a teaching certificate. She was the valedictorian of her class in 1905. Upon graduating, she accepted a teaching position at Prairie View and that is where she met her husband, Jasper Williams. Although she and Jasper met in 1907, they were married ten years later in 1917. A few years into their marriage, the couple moved to El Paso, Texas, where they purchased a drugstore and raised a family. While living in El Paso, the couple became parents of three sons – Jasper, James, and Charles.

In 1924 after a fire destroyed their drugstore, Jasper and Clara left Texas and moved near Las Cruces, New Mexico where they homesteaded 640 acres of land. The Williams utilized the land and planted pinto beans, corn, and cotton, and raised livestock. The motivating factor which led to their move to Vado, NM near the Las Cruces area was a teaching job. The teaching job was at an all African-American school, that paid $100 monthly. Clara accepted the job, but teaching at the school had its obstacles, as families were resistant and did not welcome Clara as a teacher. During the first three months of teaching, her students consisted of her two sons and three other students.

After the short distance move from Texas to New Mexico, Clara continued her education. She took correspondence courses from the University of Chicago, and then in 1928, she enrolled at New Mexico College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts. Clara would take courses at New Mexico A&M during the summer months while teaching at Booker T. Washington, although her experiences were not the same as her classmates. Despite the racial injustices that Clara faced while enrolled in college, she managed to receive a bachelor of arts in English at the age of 51. While Clara was unable to participate in the 1937 commencement ceremony, it did not impede her from pursuing her graduate studies at NMSU. Clara’s perseverance in furthering her education drove her to take graduate-level courses in the 1950s. It was evident that Clara’s educational journey was not an easy one. She encountered challenges and racial injustices along the way, but despite the challenges, she was determined to further her education to serve as an example to her children.

Clara’s three sons – Jasper, James, and Charles – all followed her educational lead and they obtained their medical degrees and became physicians. In 1951, after 40 years of teaching in Las Cruces, Clara retired and left the City of Crosses. She moved to Chicago to be closer to her sons and assisted with the opening of the Williams Clinic, and opened its doors in 1960. The clinic operated for 30 years and Clara served as the receptionist until the age of 91.

In 1994, Clara passed away at the age of 108 in Chicago, but her legacy continues. The list of her accomplishments is remarkable regardless of the injustices and obstacles she encountered while pursuing her dream of obtaining a higher education.

(Info: NEW MEXICO STATE UNIVERSITY)

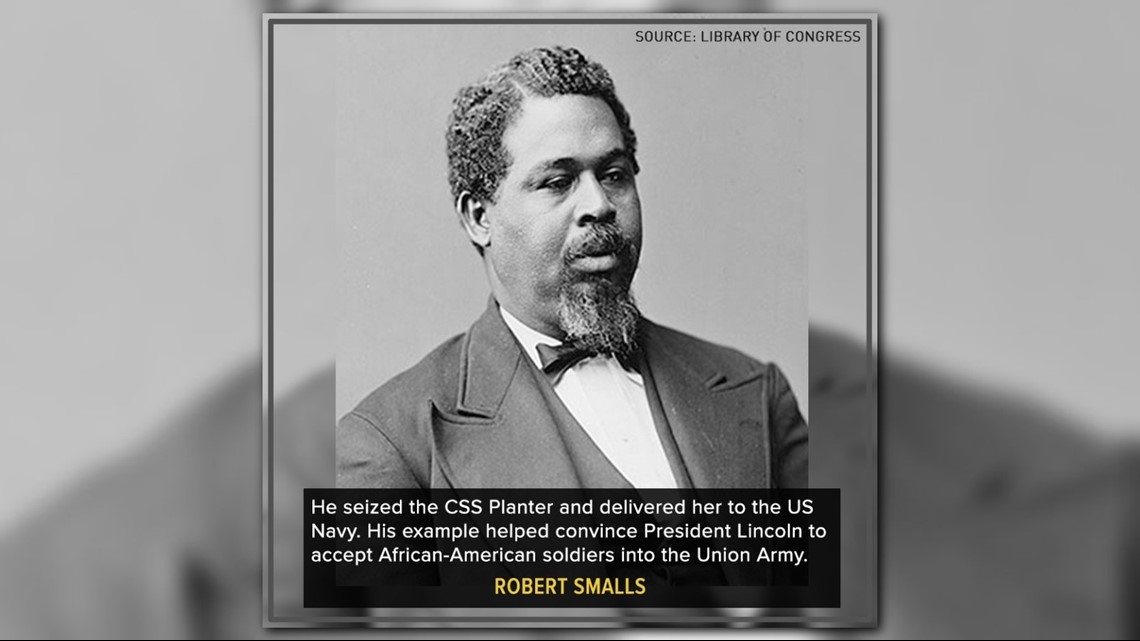

ROBERT SMALLS

Robert Smalls was born into slavery in Beaufort, South Carolina. At age twelve, Smalls was sent to Charleston to find work. Sending slaves to the city to "hire themselves out" was a common practice in the nineteenth century. Enslaved people were required to send any money they made home to their enslavers. Working at a variety of jobs aboard boats, Smalls learned to navigate the waterways of Charleston Harbor. At the beginning of the Civil War, Smalls worked as a pilot aboard the CSS Planter, a steamboat chartered by the Confederate government.

On May 12, 1862 he and other enslaved members of the crew were detailed to load some heavy guns onto the Planter to be taken to a Confederate fort. They stretched out the work so that the guns would have to remain aboard overnight. When the white captain, engineer, and mate went into town for the evening, Smalls put on the captain’s straw hat and sailed the vessel to another wharf where his family and friends were waiting. They boarded, and he sailed out of Charleston Harbor, blowing the steam whistle at the appropriate check points for safe passage past Forts Sumter and Moultrie.

Then, just out of range of their guns, Smalls raised the white flag of surrender and turned over the Planter and all the guns and military supplies aboard to the USS Onward, part of the Union blockade fleet. Through his daring act, Smalls secured the freedom of everyone on board and instantly became a Union war hero.

Rear Admiral Samuel F. DuPont wrote to Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles that “This man, Robert Smalls, is superior to any who has yet come into the lines, intelligent as many of them (contraband slaves) have been. His information has been most interesting, and portions of it of the utmost importance.”

The Southern press was, however, understandably frustrated. The Charleston Daily Courier reported that “this vessel (the Planter), which has been allowed to escape under our very noses, to the enemy with a heavy responsibility somewhere, had on board six cannon.”

Recognized for his bravery and skill, Smalls became one of the first African American pilots in the United States Navy. He was wounded April 7, 1863 while piloting the USS Keokuk during the ironclad attack on Fort Sumter. He also served as a captain for the US Navy during the siege of Charleston, 1863-1865. Despite his service, when Smalls took the Planter to a boatyard in Philadelphia, he and a white colleague attempted to board a city streetcar on a rainy day. Street cars in Philadelphia were segregated, and the conductor informed Smalls that he would have to ride on the front platform by the driver, in the rain. Rather than face the humiliation of riding on the driver's platform, Smalls and his colleague walked across the city in the rain. Reformers cited this incident in their fight for streetcar integration, which became reality in 1867.

After the Civil War, Smalls served in a variety of public offices, including the United States House of Representatives. Throughout his political career, Smalls continued to fight for equality for African Americans. In the US House of Representatives, he fought tirelessly against segregation of the military, railroads, and restaurants; opposed plans to relocate African Americans to Liberia; and served on a number of important committees. He also helped pass legislation that created the Parris Island Marine Corps Base near Beaufort, South Carolina.

After his work in Congress, Smalls was appointed the Collector of Customs in Beaufort, a lucrative federal appointment, and held the post for almost 20 years despite opposition from local white politicians.

After the Civil War, Smalls' former owners, the McKees, were on the brink of bankruptcy. With prize money he received for capturing the Planter, Smalls bought the McKee house at 511 Prince Street in Beaufort where he and his mother had been enslaved before the war. His family lived in the house for the next 90 years. When Mrs. McKee's health began to fail, Smalls allowed her to stay in her former home - an impressive act of compassion. Smalls died on February 23, 1915 and was buried in Beaufort at Tabernacle Baptist Church.

(Info: NATIONAL PARK SERVICE)

GLADYS WILLIAMS

Historians say Gladys Williams was Macon’s first Black female bandleader in the 1930s. She is widely regarded as the only female band director of her era. In the 1940s, 50s, and 60s, she was a singer, music teacher, bandleader, composer and music teacher, developing some of the greatest entertainers of that day. She is said to have had a great ear, big heart, and a harsh tongue. Her dedication to the young musicians she trained was widely known. Historians and key music figures say if Gladys Williams were alive today, she would probably have been a big star. Unfortunately, possessing the unique combination of music skills was simply rare for a woman back then.

Born Gladys Rawlins in 1908, her family was originally from Sparta, Georgia. As a young child, she was raised on Tindall Avenue in Tindall Fields, which was part of Tindall Heights of Macon. Historians say she spent much of her childhood years on crutches as a result of polio.

She began to play music by ear at age 4.

Gladys Williams studied music at the Hampton Institute in Virginia. She was a talented pianist. An anonymous white donor provided Williams with the scholarship money allowing her to attend Hampton. Some of Gladys Williams’ work remains on display at Hampton today.

Part of her legacy is the foundation she laid for the pool of musical talent that flowed out of Macon during her time. Macon’s rich music talent is recapped in the book titled, "Something in the Water." In that book, Gladys Williams is quoted. She talked about how her parents only wanted her to play traditional music, classical selections, and hymns, but her interest was blues and jazz.

“I used to sneak around and practice it when my mother was at work,” Williams reportedly said. “I can still hear my sister, 'Mama, Gladys played the blues around here all day.'"

Gladys Williams taught and performed with a long list of great entertainers in Macon and abroad. Among them included Macon teenagers like Little Richard and Otis Redding. She taught and also performed with them, as well as Lewis Hamlin and Lucas “Fats” Gonder, band members with James Brown.

A young man named Newton Collier was also among the group of student musicians trained by Gladys Williams.

Collier studied both piano and trumpet with Williams. The award-winning Macon musician recalls a lot of the historic moments surrounding Williams.

He remembers her words of advice given to a young Otis Redding Jr.

“Find your own voice, and that is just what he did,” said Collier.

Redding performed in Williams’ band and participated in her music activities at a Macon teen recreation spot.

Not only was Williams a gifted musician, but she was like a mother figure and mentor to the young musicians in the neighborhood, but her reach was far beyond Macon. Newton Collier remembers her home, where he had music lessons. He says it was a beautifully decorated home. There was a blue guest room with a studio for traveling artists.

“She had her own little hotel situation with famous artists and people who just came here to stay,” said Collier.

Williams' home was listed in the Green Book and on the route for African American entertainers.

Collier remembers a chance meeting when he arrived at Williams' home for music lessons.

“At any given time, you can go to her house and there would be somebody there -- Sammy Davis Jr. happened to be there that day and they were practicing the trumpet," said Collier.

Collier says he got to meet Sammy Davis Jr. and knew of many other famous performers like Ethel Waters staying at Williams’ home. Lena Horne, who actually lived in Pleasant Hill for a while, was also believed to be a frequent student of Gladys Williams.

Williams' son Earl Jackson traveled with the Russian version of the musical "Porgy and Bess." Often, cast members would stay at the house.

Collier says “Ms. Gladys” was quick to teach and provide practice opportunities to all who came by her home.

He credits Gladys Williams for not only being his music teacher, but the person who saved his life at a young age.

“I was about 9 or 10 years old and I was getting ready to hit the streets. I was getting ready to be a thug. I could see it coming. My daddy had left, my mother was working hard, and my aunt was working hard, so music saved my life,” said Collier. “I had something to do. I had something to practice. I had something to look forward to.”

Collier says Williams taught him an important musical skill of improvising which carried him through his career.

The city of Macon honored Gladys Williams for 25 years of service during a star-filled concert held at the Macon Auditorium on August 5, 1955.

Gladys Williams is believed to have died in the early 1980s.

MAJ. GEN. CEDRIC D. GEORGE

Maj. Gen. Cedric D. George was the Director of Logistics, Deputy Chief of Staff for Logistics, Engineering and Force Protection, Headquarters U.S. Air Force, Arlington, Virginia. He was responsible for organizing, training and equipping more than 180,000 technicians and managers maintaining the aerospace weapons system inventory. He provided strategic guidance for materiel and equipment management, fuels, vehicle management and operations, distribution, personal property and passenger traffic management. The general developed logistics readiness, maintenance and munitions policy, ensuring the readiness of the single largest element of manpower supporting Air Force combat forces globally.

Maj. Gen. George is a 1987 graduate of the ROTC program at Norwich University. He is a fully qualified maintenance officer and has held key maintenance leadership positions at the wing, major command and Air Staff levels. His commands included 49th Aircraft Maintenance Squadron, 35th Maintenance Group, 11th Wing, 76th Maintenance Wing and the Warner Robins Air Logistics Complex. He is also a Level III senior acquisition professional with a wide array of leadership experiences in Air Force and joint programs. Prior to his current position, he was the Deputy Director, Resource Integration, Deputy Chief of Staff for Logistics, Engineering and Force Protection, Headquarters U.S. Air Force, Arlington, Virginia. His duties included responsibility for enterprise-wide logistics technology vision, strategy, advocacy and policy. He oversaw logistics transformation, agile planning and technology insertion, development and implementation of innovation logistics concepts and capabilities to deliver logistics effects to the order of battle across the full spectrum of operations to enable air, space, cyber and joint forces.

(Info: ROBINS AIR FORCE BASE)

JOHN OLIVER KILLENS

John Oliver Killens was an award-winning author from Macon, Georgia. He used the power of the pen to bring about social change and give voice to the African American experience. Killens was a founder of the historic Harlem Writers Guild in New York and influenced other well-known writers like Maya Angelou and Central Georgia’s Tina McElroy Ansa.

Killens was born January 14, 1916 to Charles Mayers Killens, Sr. and Willie Lee Killens. He grew up in the Pleasant Hill community and had a love of reading at a young age. His parents encouraged him to read literature from African American writers like Langston Hughes and Richard Wright. Mrs. Killens was also the president of the Dunbar Literary Club, and introduced him to poetry. Killens’ great-grandmother’s stories of southern slavery helped develop his creative folklore knowledge and served as the catalyst to his contribution to the Black southern literature.

Killens attended the historic Ballard Normal High School in Macon and graduated in 1933. Today, this school is known as Ballard Hudson Middle School. Local historian Dr. Thomas Duval has researched the significance of Killens’ educational background of graduating from one of the earliest fully state accredited schools for blacks in Georgia. Ballard Normal High School began as Lewis Normal High school and was founded in Macon in 1868 by the American Missionary Association. Killens no doubt understood this rich educational history that started with former slaves being taught in the basement of churches in Macon.

As a nonfiction writer, Killens created books, plays, screenplays, and more. Duval explained that as a novelist, Killens understood the value of a southern Black voice to American Literature. This was particularly seen in his Pulitzer Prize-nominated novel Youngblood, written in 1954.

Killens used the southern dialect and the daily black experience to dramatize for the reader, “the raw courage against a social, political, economic and religious system which demeaned the manhood of Black people of that era,” said Duval. His fictional Black characters displayed strong “moral ethical behavior and profound wisdom.”

Before becoming an award-winning writer, Killens was an aspiring lawyer. He attended several historically Black colleges and universities between 1934 and 1936. Among the colleges he attended included Morris Brown College in Atlanta and Howard University in Washington D.C. He also attended Robert H. Terrell Law School and studied creative writing at Columbia University in New York.

John Oliver Killens also enlisted in the United States Army during World War II between the years of 1942 and 1945.

Killens’ educational contribution as a creative-writing instructor included programs at Fisk University, Howard University, Columbia University and Medgar Evers College. In 1986, he founded the National Black Writers Conference at Medgar Evers College. The Killens Review of Arts & Letters is published twice a year and is named in his honor.

John Oliver Killens died of cancer on October 27, 1987. His literary contributions include nine acclaimed novels, and many other media and printed materials. Killens even worked with actor and activist Harry Belafonte. As a writer, Killens played an important role in the Civil Rights Movement. He was armed with the pen and historical knowledge.