![National Black Political Convention.jpg [image : 79624024]](http://www.gannett-cdn.com/-mm-/d3e3353eac4ac0e90f2f07a55f18e8a472b85c65/c=220-0-2636-2065/local/-/media/2016/01/31/USATODAY/USATODAY/635898750422888818-Gary-1972-National-Political-Convention.jpg)

One of my friends believes the spirits of slaves still move across the Washington, D.C., area, their memories imprinted in the very soil beneath our feet. Indeed, the imprint of African Americans, free or slave, is in the air, the water and the soil of every corner of this nation.

I remember the places I’ve been, the neighborhoods and people in the communities I’ve lived in who have left their imprint on me. They are my hallowed grounds.

There’s Link’s Wonderland in Fort Wayne, Ind., the skating rink-bowling alley-soul food cafe where back in the ’90s, seniors watched lunchtime soap operas and sipped coffee all day.

There’s Dayton’s west side, home not only to poet Paul Laurence Dunbar, but also toZapp and Roger Troutman, the Ohio Players and a dozen other famous funk bands that in the ’70s entertained auto workers, fresh off the second shift, at bars and clubs.

And today I make my home in Virginia near a major airport and shopping mall on what was once Nokes Mountain, which local historians say was named after the area’s first black landowner, George Washington Nokes. A small farmhouse hidden by trees is all that remains of his all-black, post-Reconstruction community in the foothills of the Blue Ridge mountains.

![Seale-Jackson-NBPC.jpg [image : 79624212]](http://www.gannett-cdn.com/-mm-/06f652dd16c926e76b32b6efbb0e253eb14dc92e/c=330-0-2670-2000/local/-/media/2016/01/31/USATODAY/USATODAY/635898754755092128-Seale-Jackson-NBPC.jpg)

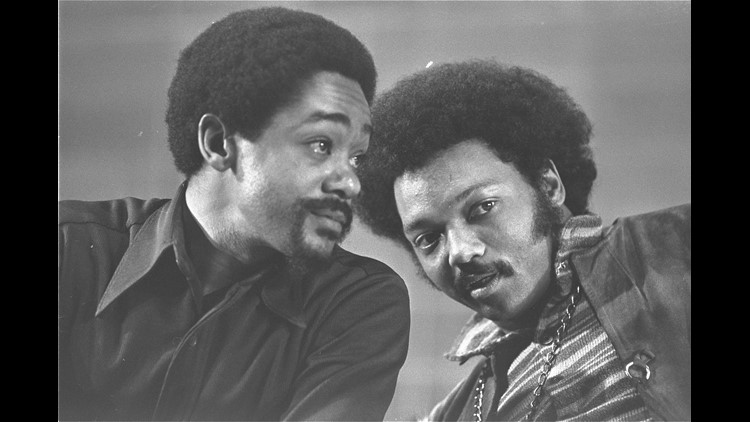

But few places hold memories more special to me than my hometown. Many people forget that the Great Migration of the last century made Gary, Ind., birthplace of Michael Jackson, a thriving destination for blacks escaping the Jim Crow South. Lost in the modern narrative of a steel city on hard times is Gary’s legacy as an inspirational center of black political power. That power reached its apex with the 1972 National Black Political Convention, where Richard G. Hatcher, one of the first black mayors of a major city, hosted 8,000 delegates and a who’s who of activists, from Amiri Baraka to Jesse Jackson, to set a national agenda for African Americans to address poverty, jobs and disenfranchisement.

In USA TODAY's Black History Month special section, Hallowed Grounds, we examine the lost memories and forgotten places where the spirits of African-American ancestors still move. In our cover package, National Park Service officials discuss a new study of Reconstruction-era sites, and historians weigh in on black cultural touchstones that should be preserved. We also look at changing neighborhoods like Chicago’s Bronzeville and East Cleveland, and changing perspectives about racism, policing and affirmative action on the nation’s college campuses.

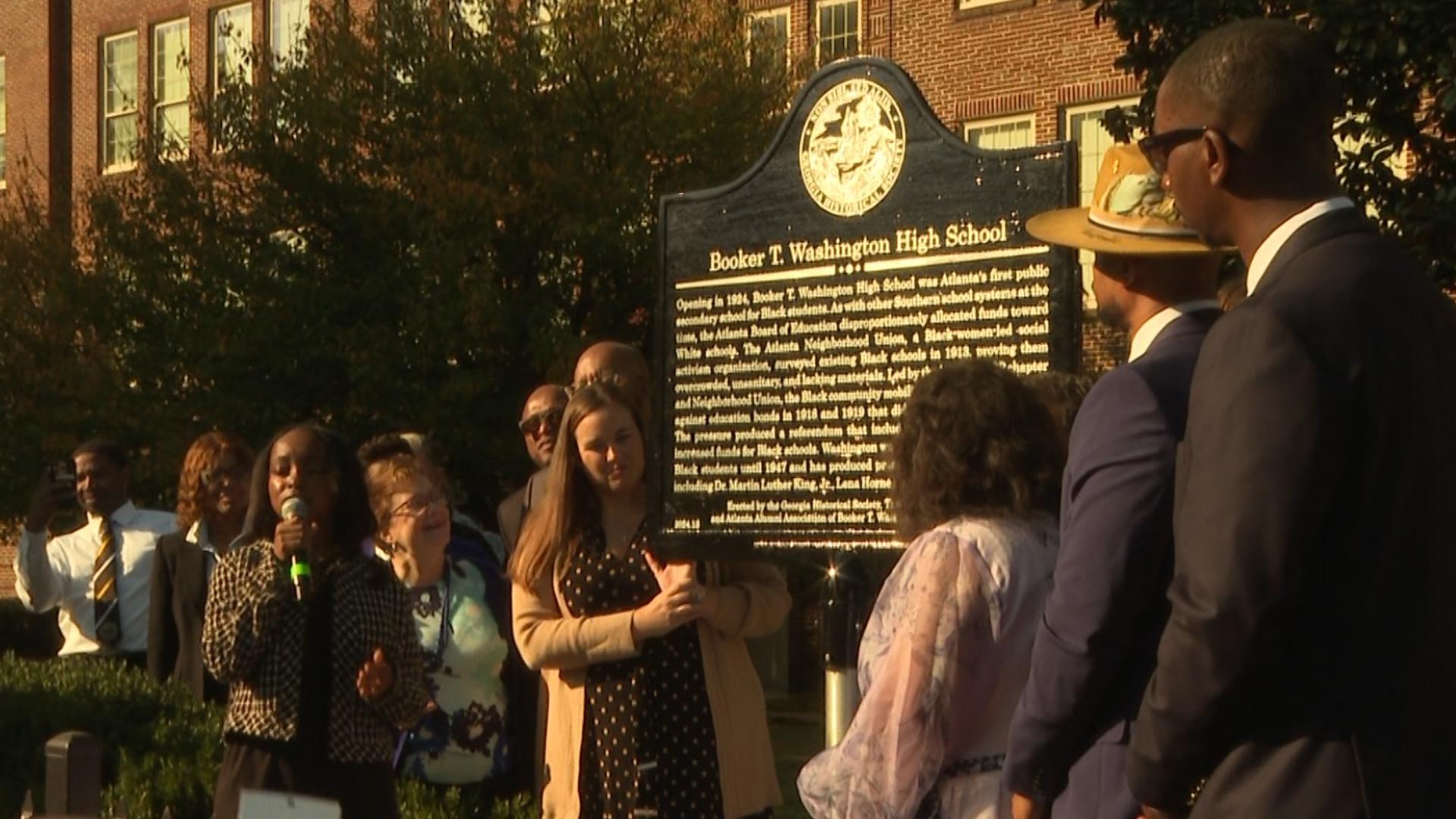

In our civil rights core, we study Stokely Carmichael and the Black Power Movement, which saw perhaps its finest and most troubled hour in the Black Panther Party. Co-founder Bobby Seale reflects on Panther pride, and Patrisse Cullors shares what herBlack Lives Matter movement draws from the past.

For more Black History Month features, see our Civil Rights in America landing page at civilrights.usatoday.com.

--

Nichelle Smith is the editor of this year's Black History Month issue. Follow her on Twitter: @NicSmith312