ATLANTA — Applying for a job can be tough as the competition for a role is fierce, with every person trying to stand out. For some applicants, they’re worried that checking a single box could be all the potential employer is judging them on.

This is the reality for the 4.6 million Georgians with some type of criminal history.

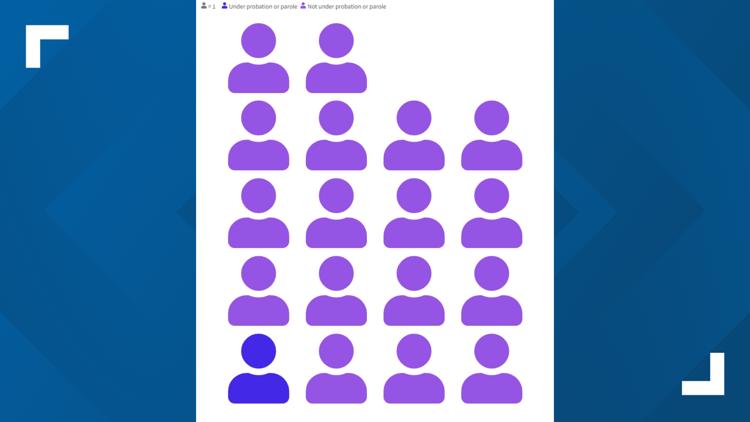

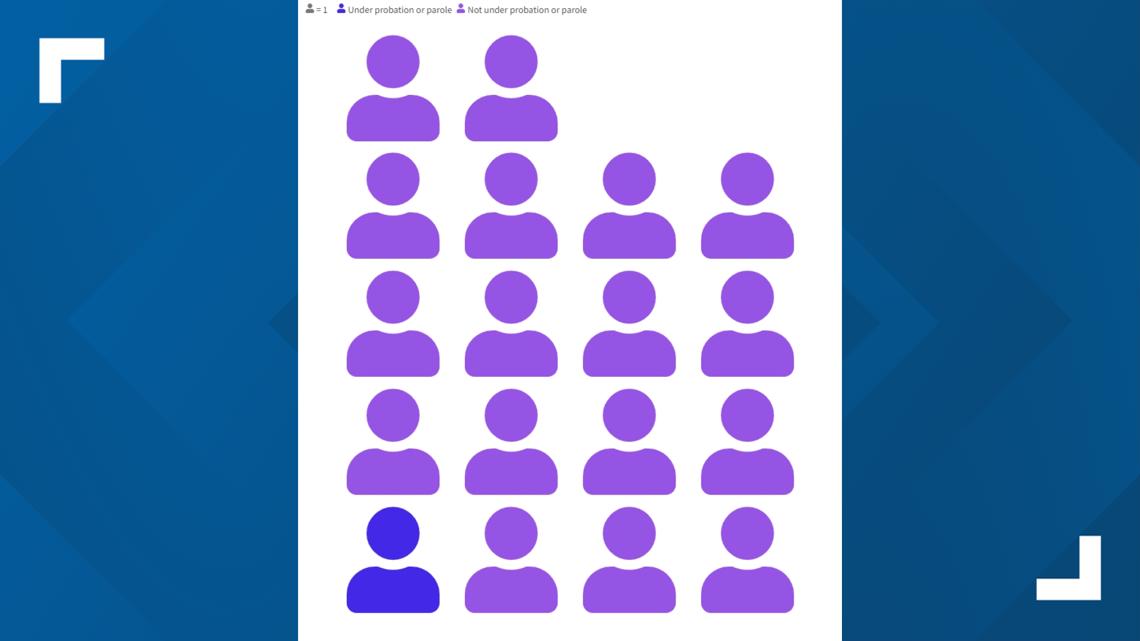

According to the Southern Center for Human Rights, Georgia has the highest correctional control rate of any state in the country, with one out of every 18 adults under probation or parole. On top of that, Georgia has the longest probation sentences of any state, according to the Prison Policy Initiative.

More eyes have been on the criminal justice system - specifically what you can and can’t do with a conviction, and some inconsistencies in these policies - amid former President Donald Trump’s ongoing legal battles. Critics point out that while Trump is running for president as the Republican nominee, Georgians with a felony conviction cannot run for or hold public office until 10 years after all sentences have been served.

For more than 35 years, the Georgia Justice Project has been working to serve and aid those impacted by the criminal justice system. Their holistically-focused assistance “touches every point of the criminal legal system,” according to GJP Policy Director Wade Askew.

GJP has helped to change 23 state laws so far, like lifting Georgia’s lifetime ban on food stamps for individuals with felony drug convictions. A 2017 law allows individuals convicted of their first felony offense to have their probation terminated after three years if all conditions are met.

Another key impact GJP was involved in was former Gov. Nathan Deal signing the Ban the Box executive order in 2015. The order “removes questions about criminal history from the original employment application for state employment and postpones the background check until the interview stage. Employers may only screen for relevant criminal records.”

While Ban the Box was a win for GJP and similar organizations, advocates say there are still several significant barriers. For example, all 26 University System of Georgia schools still have criminal history questions on their applications, which groups like the Georgia Coalition for Higher Education in Prison are working to change. In fact, Georgia-based group Beyond the Box sponsored a bill in the state legislature this year to remove those questions from USG applications. However, the bill did not pass.

“Questions from employers, from places that offer housing, that look into somebody's criminal record, are doing nothing but creating unnecessary challenges for people who may be trying to do the right thing after they have gone through the sentencing of the court,” Patrick Rodriguez, co-executive director of GACHEP, said.

RELATED: Carbon monoxide leak in Fulton County Jail kitchen | Latest issues on conditions plaguing facility

Since Ban the Box applies only to state jobs, many job applications still have that barrier for formerly incarcerated applicants. This can create a “trap,” as Rodriguez put it: Individuals on parole need a job to successfully complete their sentence and not get a violation, but the current system makes it harder to actually get a job when one has a record.

“How does that person successfully navigate supervision if the very thing that can cause a violation, society puts in place and says ‘you can't succeed in this area that's needed to be able to be successful,’” Rodriguez said.

Having more and stricter reentry barriers doesn’t just negatively impact individuals - it can impact the state as a whole, data show. Because individuals serving a felony sentence cannot vote, 3.79% of Georgia’s population is disenfranchised - the ninth highest rate in the country - according to Askew. Georgia has the sixth highest overall population of disenfranchised citizens: 275,089 - more than the population of Augusta.

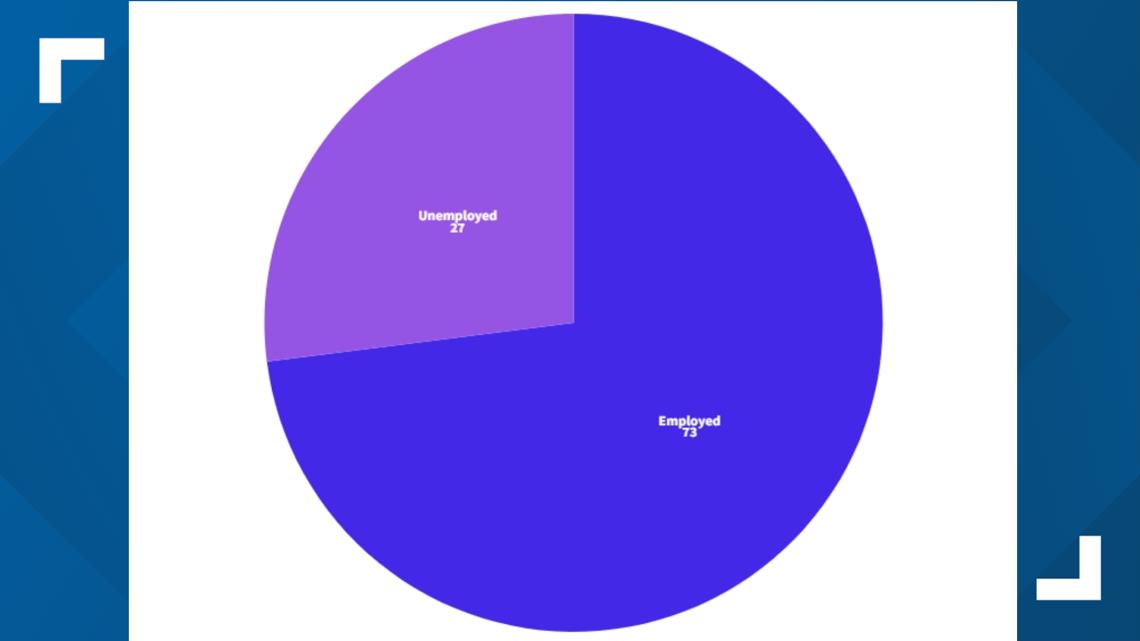

These barriers also have an economic impact. A 2018 study by the Prison Policy Initiative found that the unemployment rate of formerly incarcerated individuals was over 27% - higher than nationwide unemployment during the Great Depression.

This would mean approximately 1.2 million potential Georgia workers are unemployed.

Georgia’s GDP per capita is about $64,000, meaning the state is missing out on approximately $79.4 billion in potential economic output per year.

Askew and Rodriguez both acknowledged that completely removing all criminal history questions from all job applications isn’t the goal, but that the questions should be limited to crimes relevant to the job at hand. For example, someone with a tax fraud conviction should have to disclose that if they apply to be an accountant.

Though they have made progress, GJP’s work is not done, according to Askew. They have several more goals they are working toward, including reducing barriers to acquiring an occupational license - something one in six jobs require - and improving expungement laws.

“Folks who have had contact with the criminal legal system - that should not define the rest of their life,” Askew said.