MINNEAPOLIS — Editor's note: Some of the images depicted in the video and testimony are graphic. Have a question you'd like to hear our trial experts answer? Send it to lraguse@kare11.com or text it to 763-797-7215.

Monday, April 5

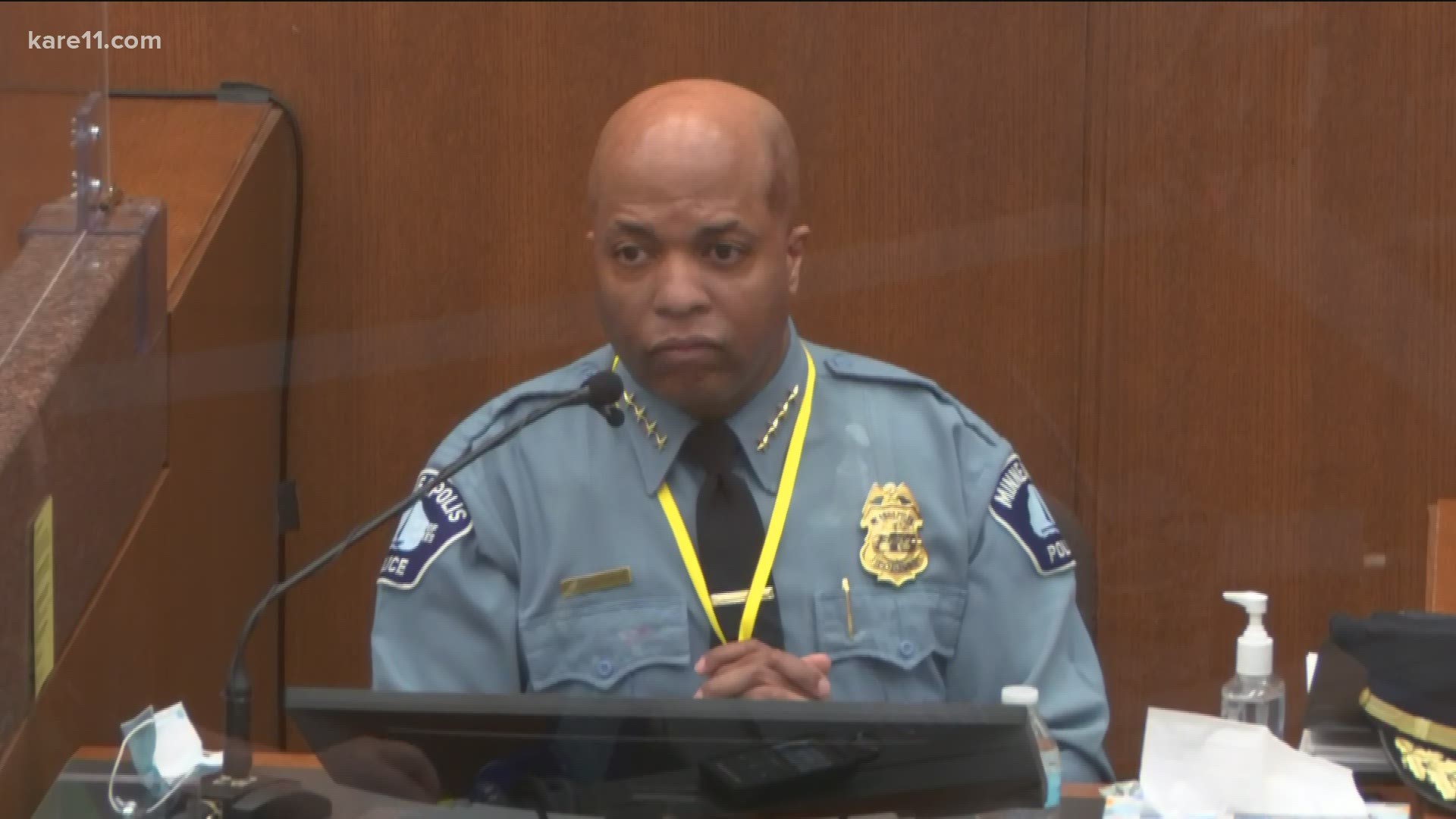

- Minneapolis Police Chief Medaria Arradondo said Derek Chauvin violated multiple department policies in his restraint of George Floyd

- Former head of training for MPD: 'I don't know what kind of improvised position that is'

- Doctor who pronounced George Floyd dead testified he believed hypoxia caused the cardiac arrest

- Judge told attorneys that testimony from officers condemning Chauvin's use of force will soon become 'cumulative'

- Friday, veteran Minneapolis police officer Lt. Zimmerman called Chauvin's actions 'totally unnecessary'

Minneapolis Police Chief Medaria Arradondo testified against his former officer on Monday, saying that Derek Chauvin violated multiple policies in his restraint of George Floyd.

Chauvin is charged with second-degree murder, second-degree manslaughter and third-degree murder in George Floyd's death. Arradondo fired Chauvin and the other three officers involved in Floyd's arrest within 24 hours.

Bystander video viewed across the globe, along with police body camera footage, showed Chauvin's knee on Floyd's neck for more than nine minutes.

Prosecutors called Arradondo to the stand late Monday morning and he testified most of the day. He said after reviewing all of the video footage, he believes Chauvin's actions violated MPD's policies on de-escalation, use of force, and rendering medical aid to a person in custody.

"Once there was no longer any resistance, and clearly when Mr. Floyd was no longer responsive and even motionless, to continue to apply that level of force to a person proned out, handcuffed behind their back, that in no way, shape or form is anything that is by policy, it is not part of our training, and it is certainly not part of our ethics or values," Arradondo said.

MPD Inspector Katie Blackwell, who was the commander of the training division at the time of Floyd's death, also testified that Chauvin's action was not a "trained technique."

"I don't know what kind of improvised position that is," she said. "So that's not what we train."

Judge Peter Cahill told prosecutors Monday morning that testimony from other officers giving opinions on Chauvin's use of force will soon become "cumulative," after the jury heard two supervisors do so last week.

"You're not going to be able to ask every officer, 'What would you have done differently?'" Cahill said.

The first witness to take the stand Monday was Dr. Bradford Langenfeld, who attempted to resuscitate George Floyd and then pronounced him dead on May 25, 2020. He said at the time he believed that "hypoxia," or insufficient oxygen, was the most likely cause of cardiac arrest.

LIVE UPDATES

Monday, April 5

4:25 p.m.

Defense attorney Eric Nelson cross-examined Katie Blackwell, the former commander of MPD's training division, at the end of the day Monday.

He confirmed with Blackwell that officers can learn about multiple topics in any given block of training, that the instructors vary, and that some of them may use materials from past trainers.

Blackwell also confirmed MPD was served with a search warrant to acquire 30,000 pages of training materials administered to the four former officers charged in Floyd's death.

The judge adjourned court for the day after Blackwell left the stand. There will be a motions hearing at 8:30 a.m. Tuesday, and testimony is expected to resume around 9:15 a.m.

3:50 p.m.

After spending most of the day Monday questioning Minneapolis Police Chief Medaria Arradondo, prosecutors called Katie Blackwell to the stand.

Blackwell has been the inspector of the Fifth Precinct since January. Before that, she was the commander of the MPD training division.

Blackwell said she has known and worked with Derek Chauvin for about 20 years.

Prosecutor Steve Schleicher pulled up Chauvin's training records for the jury. He asked Blackwell to explain what was involved in each training. She said officers are trained in defensive tactics and use of force every year.

The records show that Chauvin attended a 40-hour crisis intervention training in 2016. Blackwell said that training covers CPR and lifesaving measures, including positional asphyxia.

Blackwell testified that officers are trained to move someone from a prone position to a side position to avoid positional asphyxia "as soon as possible." She said she's been trained in that danger since she first became an officer.

Schleicher asked Blackwell to look at a photo of Chauvin's knee on Floyd's neck.

"Is this a trained technique that's by the Minneapolis Police Department when you were overseeing the training?" Schleicher asked.

"It is not," she said. "Use of force according to policy has to be consistent with MPD training."

She said they train the conscious and unconscious neck restraint.

Blackwell testified that per policy, a neck restraint is compressing one or both sides of the neck using an arm or leg. But MPD trains officers to use one arm or two arms.

"I don't know what kind of improvised position that is," she said. "So that's not what we train."

2:20 p.m.

Defense attorney Eric Nelson began his cross-examination of Minneapolis Police Chief Medaria Arradondo by asking how long it has been since he arrested someone. The chief acknowledged that it has been a long time.

Nelson asked Arradondo several questions about the MPD use-of-force policy. He asked the chief to describe the difference between active aggression and active resistance.

Arradondo confirmed that MPD policy has changed over the years.

Nelson also asked Arradondo to confirm that the "objective reasonableness" standard means that an officer on a scene has to make decisions based on the information they have at the time. Hindsight cannot be used when making a judgment about whether the decision was reasonable.

Nelson asked Arradondo if de-escalation can include the use of force. He said he is not familiar with that.

"Threatening use of force or threatening verbally, I'm more familiar with that," he said.

Nelson asked Arradondo about the "maximal restraint technique." The chief described it as attaching the legs to the waist with a cord, also called a "hobble."

A supervisor has to be called to the scene and officers are not allowed to transport someone in that position due to the risks to their breathing.

Arradondo acknowledged that the officers could have been attempting to use the maximal restraint technique with Floyd, but without the "hobble" device.

Nelson asked if the use of force is a "constant reevaluation," and Arradondo agreed. Nelson also asked if planning to use a hobble, and then deciding not to, might be considered a "reduction in the use of force." Arradondo first confirmed that Nelson was speaking generally, and not specifically about the events of May 25. He then agreed.

Nelson asked Arradondo about MPD policy regarding neck restraints and chokeholds. The chief confirmed that a chokehold is from the front, and obscures the airway and trachea. That's considered deadly force.

Nelson said that according to policy, a neck restraint is defined as constricting one or both sides of a person's neck with an arm or leg without applying direct pressure to the trachea or airway. Arradondo said he thinks "light to moderate pressure" is important to note.

The policy also differentiates between a conscious and unconscious neck restraint, Nelson said. In an unconscious neck restraint, the person is rendered unconscious. Both were permitted by MPD policy on May 25, 2020, Arradondo confirmed.

Arradondo said he has formed the opinion that Chauvin was using a conscious neck restraint.

Nelson asked if using a knee on someone's neck to restrain them is against MPD policy.

Arradondo clarified, "It is contrary to our training to indefinitely place your knee on a proned, handcuffed individual for an indefinite period of time."

The chief said that the critical decision making model, including taking in new information and the level of threat, factors into why he would "vehemently disagree" that Chauvin's use of force was appropriate in the situation.

Nelson showed the chief a segment of bystander video, side by side with the same timeframe from the perspective of J. Alexander Kueng's body camera. He asked Arradondo to confirm that in the body camera video, it looks like Chauvin's knee is on Floyd's shoulder blade rather than his neck.

Upon redirect, Arradondo told the prosecution that paramedics were already on the scene at that moment in the video. He said prior to that, he only saw Chauvin's knee on Floyd's neck.

Arradondo told prosecutor Steve Schleicher that using a hobble is the only sanctioned way to use the maximal restraint technique. However, he said with or without the hobble, a supervisor would need to visit the scene “because of the severity of risk."

"Because of the severe nature of making sure that that individual can breathe, we have to get that individual into a side recovery position to make sure that their airway is not obstructed," he said. "That’s paramount." He added that the side recovery position is supposed to be "immediate."

1:30 p.m.

After a lunch break, prosecutor Steve Schleicher continued questioning Minneapolis Police Chief Medaria Arradondo.

Schleicher asked Arradondo to talk through the de-escalation options written into MPD policy. He said that officers are trained in these different techniques.

"This body of knowledge that they've been taught should at least be forefront" when officers respond to a scene, the chief said.

MPD receives more than 100,000 calls for service per year. In 2019, Arradondo said about 4,500 of those were calls for an “emotionally distressed person."

Arradondo said MPD policy for dealing with individuals in crisis indicates that officers are told to use de-escalation and incorporate the values of "protection, safety and sanctity of life."

The chief said Minneapolis police officers are trained to provide basic medical care, because they often arrive at a scene before EMS gets there.

"It's very vital because those seconds are vital," he said. "Officers carry tourniquets."

Arradondo said the "duty to render aid" is written into MPD policy. In a medical emergency, the policy states that while waiting for an ambulance, the officers "shall provide any necessary first aid consistent with their MPD training as soon as practical."

Minneapolis police officers also carry Narcan, the chief said, to administer to a person experiencing an overdose.

Schleicher asked Arradondo about the MPD use-of-force policy, and Arradondo said that the "sanctity of life" has been a cornerstone of the policy since 2016.

"Of all the things that we do as peace officers for the Minneapolis Police Department," Arradondo said, "It is my firm belief that the one singular incident we will be judged forever on, will be our use of force."

He said while it is important that his officers get home safe at night, it is also important that their community members get home safe.

Arradondo said using a restraint is considered use of force. The standard MPD operates under is "objectively reasonable force." That's further defined as: "The amount and type of force that would be considered rational and logical to an officer on the scene."

The factors the officers are asked to use are:

- The severity of the crime

- Whether the person poses an immediate threat to officers

- Whether the person is actively resisting arrest or fleeing

Schleicher asked Arradondo about the crime of passing a counterfeit $20 bill, which was the original call that led to Floyd's arrest. Arradondo said it would not typically lead to an arrest, and would not be considered severe especially in light of the recent higher rates of violent crime in Minneapolis.

Arradondo explained the MPD's "critical decision making model." He said it's based on research that shows if officers treat people with respect and establish "neutral' engagements, "our communities are more likely to cooperate with us." He said employee wellness goes up, as well.

The model starts with gathering information, then threat or risk assessment, then authority to act. An officer would go back to their training in MPD policy to determine what authority they have to act at that point, Arradondo said. The next step is "goals and action." Arradondo said the purpose of the model is to develop consistency in the way officers respond to the community.

Arradondo said that when someone is handcuffed, officers have a "duty of care" to that person.

"When someone is in our custody, regardless if they're a suspect, we have an obligation to make sure that we provide for their care," he said.

Schleicher showed the jury portions of MPD policy dealing with chokeholds and neck restraints. One action that is sanctioned when a subject is actively resisting and other methods have failed is an "unconscious neck restraint," with the aim of causing the person to pass out. However, that method is not to be used against subjects who are merely "passively resisting," Arradondo confirmed.

Arradondo said he first learned about George Floyd the night of May 25, 2020 as Floyd was being transported to HCMC. At that point, the chief was told that Floyd would likely not make it. He said he contacted the BCA, which handles the investigation for "critical incidents." He then briefed Minneapolis Mayor Jacob Frey.

The chief asked his deputy to pull up the surveillance camera from 38th and Chicago so that he could watch footage of what happened. He could not hear audio and could only see the backs of the officers, he said.

"I viewed that video in its entirety and quite frankly there was really nothing in terms of the actions ... that really jumped out at me," he said.

Then close to midnight, Arradondo said a community member contacted him and asked him, "Chief, have you seen the video of your officer choking and killing that man at 38th and Chicago?" Within minutes, he said he saw the bystander video that would soon go viral across the country and the world.

At this point, Arradondo told Schleicher he has reviewed the surveillance video, bystander video and body camera videos from the officers involved.

Arradondo said Chauvin's actions were not in line with MPD de-escalation policy.

"That action is not de-escalation, and when we talk about the framework of our sanctity of life and when we talk about the principles and values we have, that action goes contrary to what we're taught," he said.

He said Chauvin's technique is not a "trained" Minneapolis Police Department technique and "it violates our policy."

"A conscious neck restraint by policy includes light to moderate pressure," he said. "When I look at the facial expression of Mr. Floyd, that does not indicate light to moderate pressure."

Arradondo said Chauvin's actions also violated the department's use-of-force policy.

"It has to be objectively reasonable," he said. "We have to take into account the circumstances, information, the threat to the officers, the threat to others, and the severity of that. So that is not part of our policy, that is not what we teach."

Arradondo said the restraint should have ended "once Mr. Floyd had stopped resisting. And certainly once he was in distress and trying to communicate that."

"Once there was no longer any resistance, and clearly when Mr. Floyd was no longer responsive and even motionless, to continue to apply that level of force to a person proned out, handcuffed behind their back, that in no way, shape or form is anything that is by policy, it is not part of our training, and it is certainly not part of our ethics or values," Arradondo said.

The police chief also said that Chauvin violated the policy in terms of rendering aid, by not giving Floyd medical attention.

11:15 a.m.

Minneapolis Police Chief Medaria Arradondo took the stand late Monday morning to testify in the trial of his former officer.

Prosecutor Steve Schleicher asked the chief about the department's motto: "To protect with courage and serve with compassion."

"We are oftentimes the first face of government that our communities will see, and we will oftentimes meet them at their worst moments," Arradondo said. "The badge that I wear ... means a lot, because the first time that we interact with our community members may be the only time that they have an interaction."

Arradondo added, "It's very important that we meet our community in that space, treating them with dignity."

Schleicher asked Arradondo about trainings and continuing education for police officers. He said the trainings should, and do, evolve with the times.

Arradondo told the prosecutor that as a patrol officer, he has had to use force before. Schleicher asked the chief to talk about his promotion up through the ranks with Minneapolis police, and then asked for an overview of the department structure.

Schleicher asked Arradondo about the pre-service and continuing education trainings that MPD officers receive.

Arradondo said in pre-service training, recruits and cadets learn about city law, procedural justice, critical thinking, defense tactics, and "basic indoctrination into the Minneapolis Police Department." They then go into field training, where they're teamed up with a mentor for several months.

Once they're fully sworn in, officers are required to take annual in-service trainings on topics like critical incident training, crisis intervention training, defensive tactics and basic CPR, Arradondo said.

"We put a lot of time, energy and resources into our training," he said. "Training is absolutely, vitally essential to use as a department."

He said this recurring training re-emphasizes "not only our policies, but really our values as a police department, and what our community expects of us."

Arradondo said the training is important because police officers do not have the luxury of being judged on their "body of work." He said community members will instead say, "I'm going to grade you on how you're doing during this call, during this interaction."

The chief said trauma impacts not only the community, but the officers who serve it.

"We do a great deal of training and work on officer wellness, because we need to make sure that our officers are well when they're interacting with our communities," he said.

Arradondo said Minneapolis police officers are required to be familiar with department policies and procedures.

Schleicher then asked the chief about the department's "code of ethics" and the professional policing policy.

"It's really about treating people with dignity and respect above all else, at the highest level," Arradondo said. "It's that we see each other as necessary, that we value one another, and it's really about treating people with the dignity and respect that they deserve."

Schleicher asked the chief to read two bullet points from the MPD's professional policing policy.

"Be courteous, respectful, polite and professional," and "Ensure that the length of any detention is no longer than necessary to take appropriate action for the known or suspected offense."

Arradondo said the department has implemented policy to inform officers that civilians have a First Amendment right to record audio or video of them, as long as they are not obstructing the officers' activity. He said that policy has been in place since May of 2016.

The chief explained the concept of "de-escalation," which he described as using time, options and resources to stabilize a situation peacefully. He said de-escalation was not mentioned when he became an officer in 1989, but in the late 1990s or 2000 the term entered the conversation along with more understanding of mental health issues.

Arradondo said although the term was not yet popularized back then, he used de-escalation while on patrol. "A lot of it hinged on communication, and listening, and verbal skills," he said.

Schleicher showed the jury a section of the MPD policy that says de-escalation is "mandatory, when reasonable" to minimize the use of physical force.

The policy also directs officers to consider whether a person's noncompliance is due to an "inability to comply." Officers are told to take into account the influence of drugs or alcohol, or a "behavioral crisis."

Arradondo said that last factor is the one his officers likely encounter the most.

"If someone loses a job, that can trigger a behavioral crisis," Arradondo said. "If someone loses a loved one, that can trigger a behavioral crisis."

"When we get the call from our communities, it may not often be their best day, and they may be experiencing something very traumatic," the chief added. "We may be the first and last time they have an interaction with a Minneapolis police officer, and so we have to make it count. It matters."

10:55 a.m.

Defense attorney Eric Nelson began cross-examining Dr. Bradford Langenfeld by asking about other things that might cause hypoxia.

"Certain drugs can cause hypoxia," he said. "Agreed?"

Langenfeld agreed that drugs including fentanyl and methamphetamine can cause hypoxia.

Nelson asked the doctor about the carbon dioxide level in Floyd's blood gas sample, which was a little over 100. The doctor said 35-45 would be normal in a healthy person. Langenfeld said fentanyl can cause increased carbon dioxide levels.

Nelson asked Langenfeld if someone can still be killed by fentanyl, even if they have a history of opiate abuse. Langenfeld said yes, they can.

Nelson asked Langenfeld if he or the paramedics provided Narcan, which can reverse the effects of an opiate overdose. He said no.

Upon redirect, prosecutor Jerry Blackwell asked the doctor to clarify his last answer.

"Administering Narcan to someone who potentially suffered a fentanyl overdose, once that person is in cardiac arrest, the administration of Narcan would provide no benefit," Langenfeld said.

The doctor also clarified that carbon dioxide would be expectedly high when someone is in cardiac arrest. "In my estimation the blood gas in this case wasn't very strong evidence for one cause or another," he said.

9:50 a.m.

The state called the doctor who pronounced George Floyd dead to the stand on Monday.

Prosecutor Jerry Blackwell questioned Dr. Bradford Wankhede Langenfeld, who said that he tried to resuscitate Floyd on May 25, 2020. He said Floyd was in cardiac arrest when he came into the Hennepin County Medical Center.

Floyd arrived in the emergency room at about 8:55 p.m., Langenfeld said. CPR had already been started. Blackwell asked if Floyd's heart was beating on its own at any point, and Langenfeld replied, "not to a degree sufficient to sustain life."

The paramedics who brought Floyd in said he had been restrained by officers. Langenfeld testified that they did not mention a potential drug overdose or heart attack. Those are among the possible causes of death that Chauvin's attorney plans to use in his defense.

Langenfeld told the prosecutor that he did not receive any report that officers had attempted to give Floyd CPR.

"It's well known that any amount of time that a patient spends in cardiac arrest without immediate CPR markedly decreases the chance of a good outcome," he said. "Approximately 10 to 15% decrease in survival for every minute that CPR is not administered."

Langenfeld testified that Floyd was in PEA, or Pulseless Electrical Activity, which he said can suggest hypoxia, or low oxygen.

Langenfeld described the ways he and his team attempted to resuscitate Floyd, including inserting an IV directly into Floyd's bone.

Prosecutor Blackwell asked Langenfeld to go through the "H's and T's of advanced cardiac life support" and describe conditions that can cause cardiac arrest. The doctor said he felt some causes were "less likely" based on information from paramedics and from his exam of Floyd.

He said because the paramedics did not report any heart attack symptoms, he did not think that was likely. There was also no report of an overdose, he said, so he did not feel there was a specific toxin that they could give an antidote for.

He also considered acidosis, in particular "excited delirium." He said that there was no report that Floyd was very sweaty or "extremely agitated," which are common with excited delirium. "I didn't have any reason to believe that that was the case here," he said.

Langenfeld said he felt that hypoxia, or "oxygen insufficiency" was more likely than the other possibilities. "Asphyxia" is another commonly used term.

Once Dr. Langenfeld determined that they could not resuscitate Floyd, he pronounced him dead.

9:20 a.m.

The judge held a "Schwartz hearing" off audio and video on Monday, to identify potential juror misconduct. It's currently unclear what prompted the hearing. Judge Peter Cahill said he found no evidence of wrongdoing after questioning the jurors.

Defense attorney Eric Nelson also stated his objection to last week's testimony from Lt. Richard Zimmerman, who said he believed Chauvin's conduct was "totally unnecessary."

The judge and attorneys also discussed parameters around upcoming testimony from Sgt. Ker Yang, who will testify about the Minneapolis Police Department's crisis intervention training.

Cahill said after the training sergeant and the two expert witnesses testify about whether Chauvin's use of force was appropriate, the state will need to stop focusing on that topic.

"We are getting to the point of being cumulative," Cahill said. "You're not going to be able to ask every officer, 'What would you have done differently?'"

9 a.m.

Defense attorney Eric Nelson has made a motion to have the entirety of Derek Chauvin's body camera video submitted as evidence in the trial.

The prosecution played the videos but only showed part of Chauvin's, and cut off the other officers' cameras early.

Nelson said that the videos have to be included in full to show the "totality of circumstances." But prosecutor Matthew Frank said some of the footage is not relevant, including the part that relates to whether or not Floyd passed a counterfeit bill.

The videos also include hearsay, Frank said.

Friday, April 2

The prosecution called 19 witnesses to the stand last week, including multiple Minneapolis police supervisors. In a significant moment for the prosecution, the longest-serving officer on the force and the head of the homicide unit called Chauvin's use of force "totally unnecessary." Chauvin's direct supervisor on that night said the former officer did not immediately tell him what type of force he used, or how long he used it.

The testimony during the first week was often emotional, with several witnesses breaking down into tears while recalling the events they witnessed at 38th and Chicago last year as Floyd was arrested and restrained by Minneapolis police.

The court heard from George Floyd's girlfriend Courteney Ross about their relationship and his struggles with opiate addiction; Genevieve Hansen, an off-duty Minneapolis firefighter who wanted to give Floyd medical aid at the scene; MMA fighter Donald Williams, who said he recognized Chauvin's actions as a "blood choke;" and several minors, one of whom shot the now-viral video of Chauvin kneeling on Floyd's neck.

Friday's proceedings ended early after Judge Peter Cahill said the trial was running ahead of schedule. The trial is estimated to last about four weeks.

What's ahead

Former Hennepin County Chief Public Defender Mary Moriarty told KARE 11 that this week the jury can expect to hear expert testimony involving everything from use of force to cause of death.

"Expert testimony can be dry, and sometimes depending on your expert, they can speak in language that, like anybody does in their own job, that nobody else really understands," Moriarty said. "So it's really going to be the state's job to make sure they break that down so that it's understandable to the jury."

Moriarty expects to hear more testimony this week from law enforcement on use of force, including from Inspector Katie Blackwell who was the commander in charge of MPD's training unit last year. She said we might also hear from a use of force expert put on by the state to talk about Chauvin's actions, and possibly someone from the Bureau of Criminal Apprehension.

Dr. Andrew Baker, the Hennepin County chief medical examiner, is a key witness as Floyd's cause of death continues to be a focus in the trial. He conducted the autopsy, stating the cause of death was "cardiopulmonary arrest complicating law enforcement subdual, restraint, and neck compression," and that the manner of death was "homicide."