MINNEAPOLIS — The jury in the Derek Chauvin trial heard from a key witness Tuesday: the lieutenant who was in charge of use-of-force training at the time of George Floyd's death.

Former Minneapolis police officer Chauvin is charged with second-degree murder, second-degree manslaughter and third-degree murder in Floyd's death. Video from bystanders and police body cameras showed Chauvin kneeling on Floyd's neck for more than nine minutes, several of which passed after Floyd had stopped speaking.

Lt. Johnny Mercil became a part-time use of force instructor back in 2010. He also introduced Brazilian jiu-jitsu training to the Minneapolis Police Department. Mercil described it as "a form of martial art that really focuses on leverage and body control." He said it includes using "pain compliance" techniques.

Mercil was in charge of use of force training for MPD during the time of George Floyd's death last year. Mercil said he was also in charge of reporting officers' completion of required trainings to the POST (Peace Officer Standards and Training) Board.

Prosecutors showed Mercil a photo of Chauvin kneeling on Floyd. The lieutenant testified that using a knee on a person's neck is not a trained MPD neck restraint, but "isn't unauthorized" when using force. He confirmed that once a person is handcuffed and under control, the technique would no longer be authorized.

Mercil acknowledged that Chauvin may have been drawing on other training centered on using his weight to gain control. However, Mercil told that court that officers are trained to avoid the neck and instead "put it on their shoulder and be mindful of position."

During cross-examination, defense attorney Eric Nelson was able to draw out some key points, including the fact that Mercil himself has held someone while waiting for EMS in the past.

Nelson asked Mercil if he has ever trained officers that if a person can talk, they can breathe. "It's been said, yes," Mercil said.

Direct examination

Prosecutor Steve Schleicher asked Mercil to talk through a deck of slides from a 2018 defensive tactics training, which Chauvin attended.

Mercil pointed out a slide that mentions the sanctity of life and the protection of the public. "That is the cornerstone of our use-of-force policies," he said.

Mercil said the use of force is defined as any weapon, vehicle or tool that causes pain or injury; physical strikes to the body; physical contact that inflicts pain or injury; or restraint likely to produce injury.

He also explained the concept of "proportionality" that he teaches officers.

"You want to use the least amount of force necessary to meet your objective," he said. If the lower levels do not work or are "unsafe to try," officers may use a higher level of force.

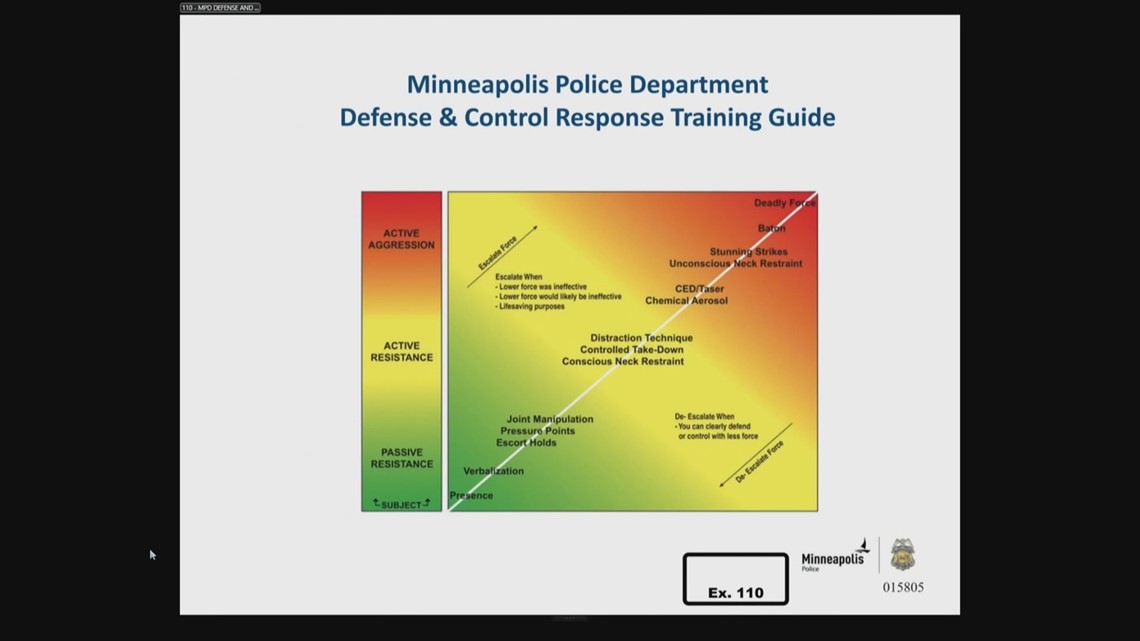

Mercil also explained the use-of-force continuum, which shows the amount of force that may be appropriate as the level of resistance increases.

Schleicher asked Mercil to read from Minnesota statute 629.32, which is included in the training. It says, "A peace officer making an arrest may not subject the person arrested to any more restraint than is necessary for the arrest and detention."

Schleicher also pulled up a training slide that warns officers about parts of the body that are more vulnerable to serious injury or death. The "red zones" include the head, neck, throat, spine, kidneys, tailbone, sternum and solar plexus.

Mercil confirmed that neck restraints were permitted by the Minneapolis Police Department at the time of Floyd's arrest. Conscious neck restraints could be used to gain control of a person, or an unconscious neck restraint could be used by "applying pressure until the person, when they're not complying, you can put enough pressure that they become unconscious and then they're complying."

Those restraints could be done with an arm or a leg, Mercil explained. He said MPD may show younger officers what it looks like with a leg, but as far as he knows, they have never trained officers to use their leg in a neck restraint.

Schleicher showed a slide that tells officers a conscious neck restraint is "OK on Actively Resistant Subjects." An unconscious neck restraint, however, is only applied:

- On subjects who are exhibiting active aggression, or;

- For life saving purposes, or;

- On subjects who are exhibiting active resistance in order to gain control of a subject and if lesser attempts at control have been or would likely be ineffective.

The slide includes a note that says neck restraints "shall not be used against subjects who are demonstrating passive resistance as defined by policy."

Schleicher showed Mercil a photo of Chauvin with his knee on Floyd. "Is this an MPD trained neck restraint?" he asked. "No, sir," Mercil responded.

"Is this an MPD-authorized restraint technique?" Schleicher asked.

"Knee on the neck would be something that does happen in use of force that isn't unauthorized," Mercil said. The length of time authorized would depend on the "type of resistance," he said.

If the person was under control and handcuffed, Schleicher asked if it would be authorized.

"I would say no," he said.

RELATED: Minneapolis police chief: Derek Chauvin's restraint of George Floyd violates department policies

Mercil said when handcuffing a person in a prone position, the knee is often used on the shoulder blade. "Control doesn't end with handcuffing always," he said.

He said it would be appropriate for the officer to remove their knee once the person is no longer resisting. Mercil also said the person should be placed in the side recovery position, or the officer should have them sit or stand up.

"There is the possibility and risk that some people have difficulty breathing when their hands are cuffed behind their back and they're on their stomach," he said.

That should happen the "sooner the better," Mercil said.

Mercil also discussed the "maximal restraint technique." He said the only authorized way to use this position, as far as he knows, is with a device called a hobble. He said in this situation, the side recovery position should also be used "as soon as possible."

Lt. Mercil said that the act of reassessing is "paramount to the use of force."

Cross-examination

Defense attorney Eric Nelson cross-examined Mercil, beginning by asking him about the "ground defense program."

"It's using techniques other than strikes to control individuals," he said. Mercil said he helped to introduce the program 10 years ago, and it includes jiu-jitsu and body control.

Mercil agreed with Nelson that sometimes officers have to do things that are unattractive, and that being a police officer can be a dangerous job.

Nelson asked Mercil if he's had people say they're having a medical emergency or "I can't breathe" while they're being arrested. He said yes. Nelson asked if there have been times when Mercil did not believe the person, and he said yes.

Mercil acknowledged that a subject may be compliant and then later become noncompliant. He also said officers can consider a large size difference when deciding how much force to use. He said the influence of controlled substances can be a factor as well.

A chokehold is defined as blocking the airway or trachea from the front, Mercil confirmed. He said he did not see Chauvin use a chokehold on any of the video he reviewed.

Mercil said the amount of pressure that an officer would need to apply to an individual to render them unconscious varies. He said a person being on controlled substances or having an adrenaline rush may speed up the process. He said in his experience, a neck restraint can render someone unconscious in "under 10 seconds."

Lt. Mercil acknowledged that MPD tells officers during training that a person could become combative afterward, but said "I have not experienced someone fighting after a neck restraint."

Mercil also confirmed that an officer can hold someone after they become unconscious.

"You can have your arm around their neck for a period of time, yes," he said.

When Nelson asked if they could be held until EMS arrives Mercil said, "I wouldn't go that far."

Mercil acknowledged that an officer has to decide if it's "worth the risk" to take handcuffs off and render medical aid to a person who's restrained. He said other safety factors, including the size and mood of a crowd and being on a busy street, could factor into the decision making model.

Lt. Mercil said that while the technique Chauvin used was not a trained neck restraint, he may have been following the training of using body weight to gain control of a person. However, Mercil said, MPD trains officers to stay away from the neck when possible, and "to put it on their shoulder and be mindful of position."

Nelson showed Mercil a training photo that shows an officer restraining a person. Mercil said in the photo, the officer's knee is on the shoulder and not the neck.

Nelson showed Mercil a series of body camera images from officers restraining Floyd. He confirmed that Chauvin's knee appeared to be between Floyd's shoulder blades while the EMT checked for a pulse.

Mercil said in his career he has held a person using body weight until EMS arrived. Nelson asked if he trains officers to do this. "As long as needed to control them, yes," he said.

Nelson asked if Mercil has ever trained officers that if a person can talk, they can breathe.

"It's been said, yes," Mercil said.

Nelson pulled up the use-of-force continuum again, showing that joint manipulation, pressure points and escort holds can be used if a person is passively resisting.

Upon redirect, prosecutor Steve Schleicher asked Mercil to confirm that a knee on the back is a "transitory" position, meant to gain control. Schleicher asked if it would be appropriate to hold someone in a prone position with a knee on top of them after they have stopped resisting, and Mercil said no.

Mercil also confirmed that he has never seen a restrained person lose their pulse and then come back to life.