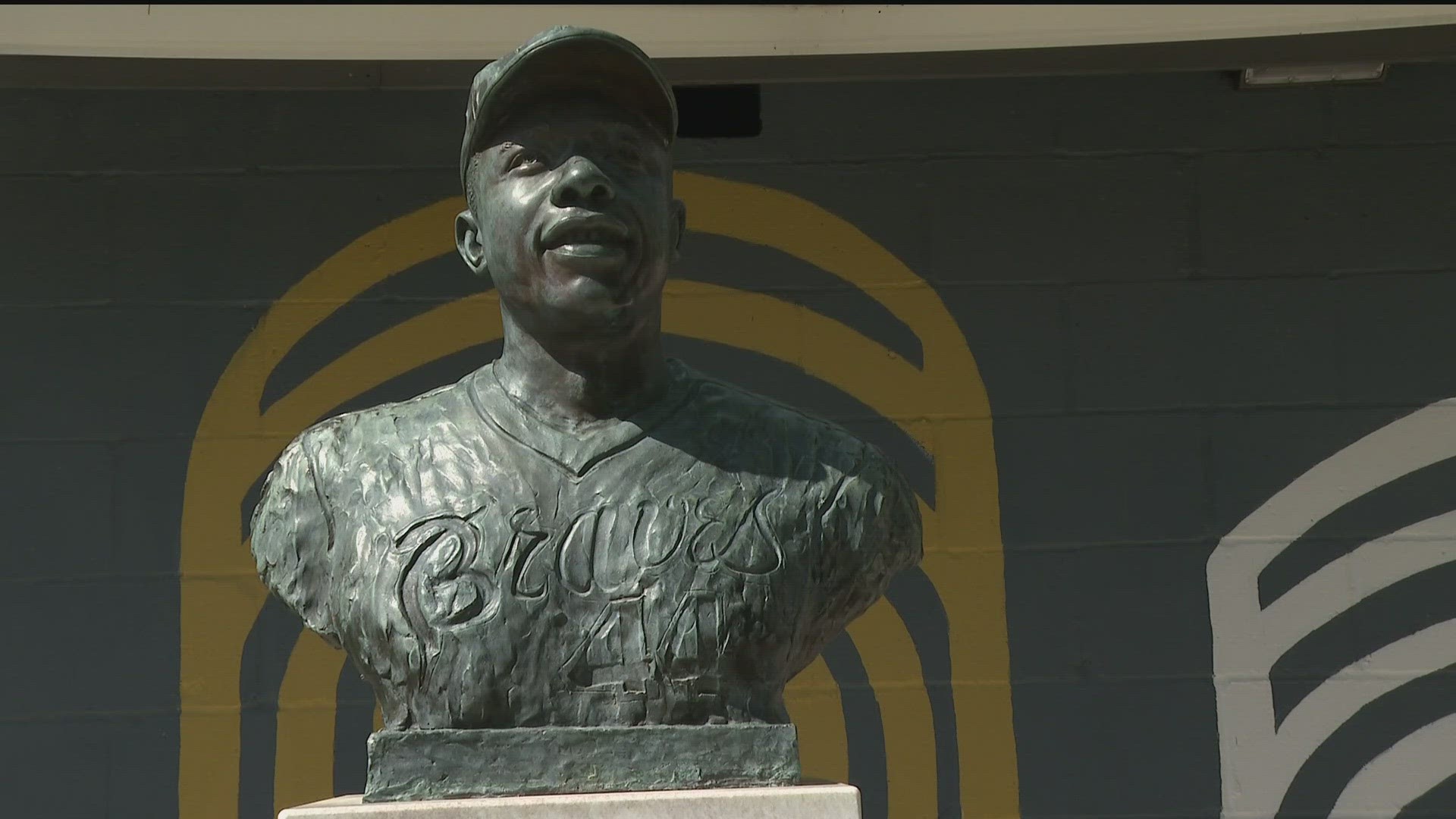

ATLANTA — CJ Stewart played in the shadow of greatness on the ball field at Adams Park in Southwest Atlanta. A bust of Atlanta Braves legend Hank Aaron sits just outside the third base dugout overlooking the field that now bears Aaron's name.

Stewart said Aaron and other civil rights leaders like the late Coretta Scott King, Ambassador Andrew Young, and the late Rep. John Lewis visited the park at times to watch games and inspire the young kids playing there. Stewart credited Aaron with sparking his dream to make it to the pros.

"When [Aaron] came here in '66, part of the charge was to help us become a major league city and truly allow us to prove that we were a city too busy to hate," Stewart said. "There was something just so human about him that allowed you to say this is a guy who’s going to be approachable, who always was giving me good advice. He gave me permission to dream."

On a day when the moon overshadowed the sun, it was on April 8, 1974, 50 years ago, that a moonshot surpassed baseball's old home run king. Stewart said Aaron's home run at Fulton County Stadium, which surpassed Babe Ruth's record, changed laws and attitudes around race in America.

Stewart, a native of Bankhead in Atlanta, would eventually play professional baseball with the Chicago Cubs organization. Little did he know, he would also model for his role model.

"He truly had a swing that was passion driven, so I made sure my hands were lined up the right way, I slid my foot back," Stewart said. "It was an outside pitch, and I was locked in at that moment with my hands at the point of contact so that Mr. Ross [Watson] could take the photos. In that moment, in my world, I hit home run 715.”

The statue that now sits inside Truist Park's monument garden drew inspiration from Stewart's stance. The Braves reached out to Stewart, requesting that he pose for the artist who designed the statue. The artistry showing the Braves' home run king mid-swing bears Stewart's body with Hammerin' Hank's head.

Stewart said he had to hold poses for several seconds at a time, but studying the stance for years helped mark an immortal feat that etched Aaron's name in major league lore.

Now, swing by swing and base by base, Stewart is showing kids like 9-year-old James Palmer how to step out of the shadows to find their own light. He runs the Lead Center for Youth, which uses sports to reach kids in underserved communities.

"We use the sport of baseball to help black boys overcome what we call the three curveballs that threaten their success: crime, poverty and racism," Stewart said.

James is in his first year in the Lead program. He plays outfield and said he was inspired by players such as Mike Trout and Ronald Acuna, Jr. He said he wants to play baseball professionally when he grows up.

"You gotta show leadership and be respectful to yourself and others," James said "All you gotta do is work hard, follow your coaches and follow directions. It's going to lead you to success."

Stewart is reminded daily, by his role model and by his students, that before the numbers and beyond the scores, it all started with a dream.

"A lot of these folks made sure things were able to be set so that way disenfranchised communities in this city would have opportunity to win at the game of life," Stewart said. "This is one of those things that allows the inner city of Atlanta to remain connected to Mr. Aaron."