ATLANTA — The 1911 Peace Monument sits near the entrance gate to Atlanta's Piedmont Park at 14th Street and Piedmont Avenue. In its original form, the statue included inscriptions commemorating post-Civil War reconciliation which focused on white Confederate veterans while ignoring blacks.

It is one of four monuments to the Confederacy, which, in a majority African American city like Atlanta, would, under any other circumstance, become a target for removal or relocation.

But lawmakers in Georgia, as in several other Southern states -- including Alabama, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia -- have gotten laws placed on the books to protect Confederate monuments.

As a result, city leaders, working together with the Atlanta History Center, have created informational markers to place near the Peace Monument to put its presence into context.

A similar marker is being placed next to the historic monument on Peachtree Battle Avenue near the Peachtree Road intersection. Two others are being placed adjacent to monuments in historic Oakland Cemetery -- one near the Confederate Obelisk and the other next to the Confederate Lion statue dedicated to the unknown Confederate dead buried there.

According to a report from the City of Atlanta which was commissioned in 2017 by then-mayor Kasim Reed, the Peace Monument, which was dedicated on October 10, 1911, was erected by the Old Guard of the Gate City Guard to commemorate reconciliation for whites only at the time, leaving out the African American perspective and civil rights.

This took place at the height of the Jim Crow Era, according to the city's report, which pointed out that the Atlanta Race Riots took place in 1906 and the rebirth of the Ku Klux Klan at Stone Mountain occurred in 1915.

One of several inscriptions on the plaque includes the notation, "The Gate City Guard, under the command of Captain Joseph F. Burke, Desiring to restore fraternal sentiment among the people of all sections of our country, and ignoring sectional animosity, on October 6th, 1879, went forth to greet their former adversaries in the Northern and Eastern states, inviting them to unite with the people of the South to heal the Nation’s wounds in a peaceful and prosperous reunion of the states. This 'mission of peace' was enthusiastically endorsed by the military and citizens in every part of the union and this monument is erected as an enduring testimonial to their patriotic contribution to the cause of national fraternity."

The plaque was dedicated by Simeon E. Baldwin, governor of Connecticut and Hoke Smith, governor of Georgia.

The Gate City Guard still exists today as an organization which holds a rededication ceremony for the monument annually, each October.

The city's report said that the Peace Monument, along with the other three monuments would need to have contextual markers added.

"Many white Southerners viewed the war [through] the lens of Lost Cause mythology," the marker says, which points out its total exclusion of all African Americans -- the four million enslaved and the nearly 200,000 who served in the United States Army.

"It describes the reunion of the states as 'prosperous' and recognizes the Peace Mission's cause as 'national fraternity,' ignoring the acceptance of segregation and white supremacy by both Southern and Northern populations," the marker states. "This monument should no longer stand as a memorial to white brotherhood; rather, it should be seen as an artifact representing a shared history in which millions of Americans were denied civil and human rights."

In 1935, the Old Guard of the Gate City Guard also placed a smaller historic monument on Peachtree Battle Avenue near the corner of Peachtree Road to commemorate the July 1864 Civil War Battle of Peachtree Creek.

Like the Peace Monument, this monument was meant to pay tribute to both Confederate and Union soldiers, as well as veterans from the Spanish-American War and World War I. The monument regards all of those soldiers as patriots.

Atlanta city officials, along with the Atlanta History Center, have placed a contextual marker next to the Peachtree Battle Monument similar to the one adjacent to the Peace Monument. The new marker points out that while African Americans were granted full citizenship rights following the Civil War, Jim Crow laws and segregation existed throughout the South, which prevented equal status for African Americans throughout the region.

A similar contextual marker was being placed in Oakland Cemetery next to the Confederate Obelisk, which was erected in 1873 by the Atlanta Ladies Memorial Association to honor the Confederate dead.

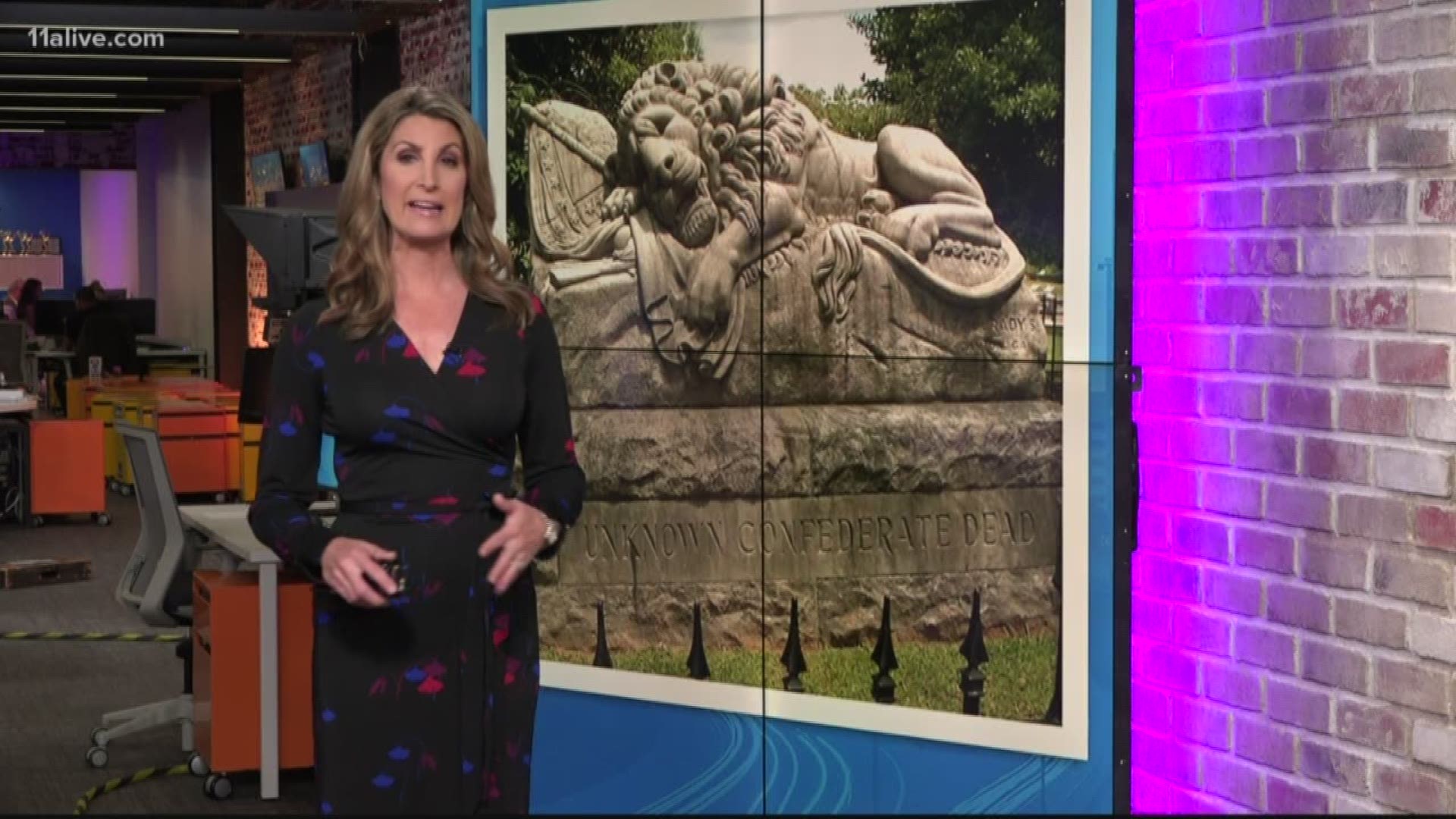

Another contextual marker is being located next to the Lion of the Confederacy memorial statue in Oakland Cemetery. The lion statue was also erected and dedicated by the Atlanta Ladies Memorial Association in 1894. It serves as a headstone for 3,000 unknown Confederate dead buried in the cemetery.

In a release, the Atlanta History Center said that since the two monuments at Oakland Cemetery are featured as part of the cemetery's walking tours, the markers there would provide additional opportunities to educate and engage visitors.

Those two monuments represent the early years of Confederate memorialization which, as opposed to the Jim Crow-era and more recent Confederate memorials, focused on mourning the loss of life. Many monuments of that era were situated in cemeteries.

According to a release from the Atlanta History Center, language for the Oakland Cemetery markers was developed by the Historic Oakland Foundation, in consultation with independent historians and scholars from Kennesaw State University and Georgia State University.

The city's report said maintenance of both statues is funded by the Historic Oakland Foundation. Atlanta History Center officials said the contextual markers for the statuary in the cemetery should be installed by Tuesday.

According to the Associated Press, municipalities and universities around the nation began debating on whether to remove Confederate statues after self-avowed white supremacist Dylann Roof killed nine black worshippers at a historically black church in Charleston, South Carolina in the summer of 2015. Roof had posted photos of himself with a Confederate battle flag on social media.

Additional attention was brought to the debate in August 2017 when a violent rally occurred in Charlottesville, Virginia which created greater debate across the nation over the presence of Confederate monuments. Days after the Charlottesville rally, the Peace Monument was vandalized with red paint. Confederate monuments and statues in other communities have been vandalized in the time since.

Speaking with the Associated Press, Atlanta History Center President and CEO Sheffield Hale said that the project puts the city ahead of other communities grappling with what to do about their monuments.

“It’s telling the truth, and it’s also giving people an opportunity to have a discussion around facts,” Hale said. “The goal is to start a community discussion.”

One hope in Atlanta is that adding context in the form of the markers “will take some of the oxygen — the accelerant — out of the room” and make it less likely that statues will be vandalized, Hale said.

The Atlanta History Center has created a Confederate Monument Interpretation Guide, which provides a tool to "help put Confederate monuments into historical perspective and foster dialogue about the future of these monuments."

It points out that while many monuments around the nation were created to honor the Confederate dead, most of them were created in the years of the Jim Crow era and later, primarily as a measure to directly oppose the cause of civil rights and racial equality.

"I think in a lot of cases once people see the power of contextualization, some people might decide they'd like to keep them there as a way to show how far we've come, or the journey that we've had, and explain what was going on at the time they were erected," Hale told the Associated Press.

MORE HEADLINES