ATLANTA — ATLANTA – Georgia voters will go back to the polls in January in a state that is one of only a handful that requires runoffs for statewide offices.

None of the candidates for Georgia’s two Senate seats won a majority of the vote during the November General Election. That means a pair of runoffs on January 5th.

Candidates for statewide offices must not only get the most votes but receive more than 50% of the vote to be declared the winner in Georgia. Otherwise, the top two candidates square off again in a runoff. In most states, the candidate with a plurality of the votes is declared the winner.

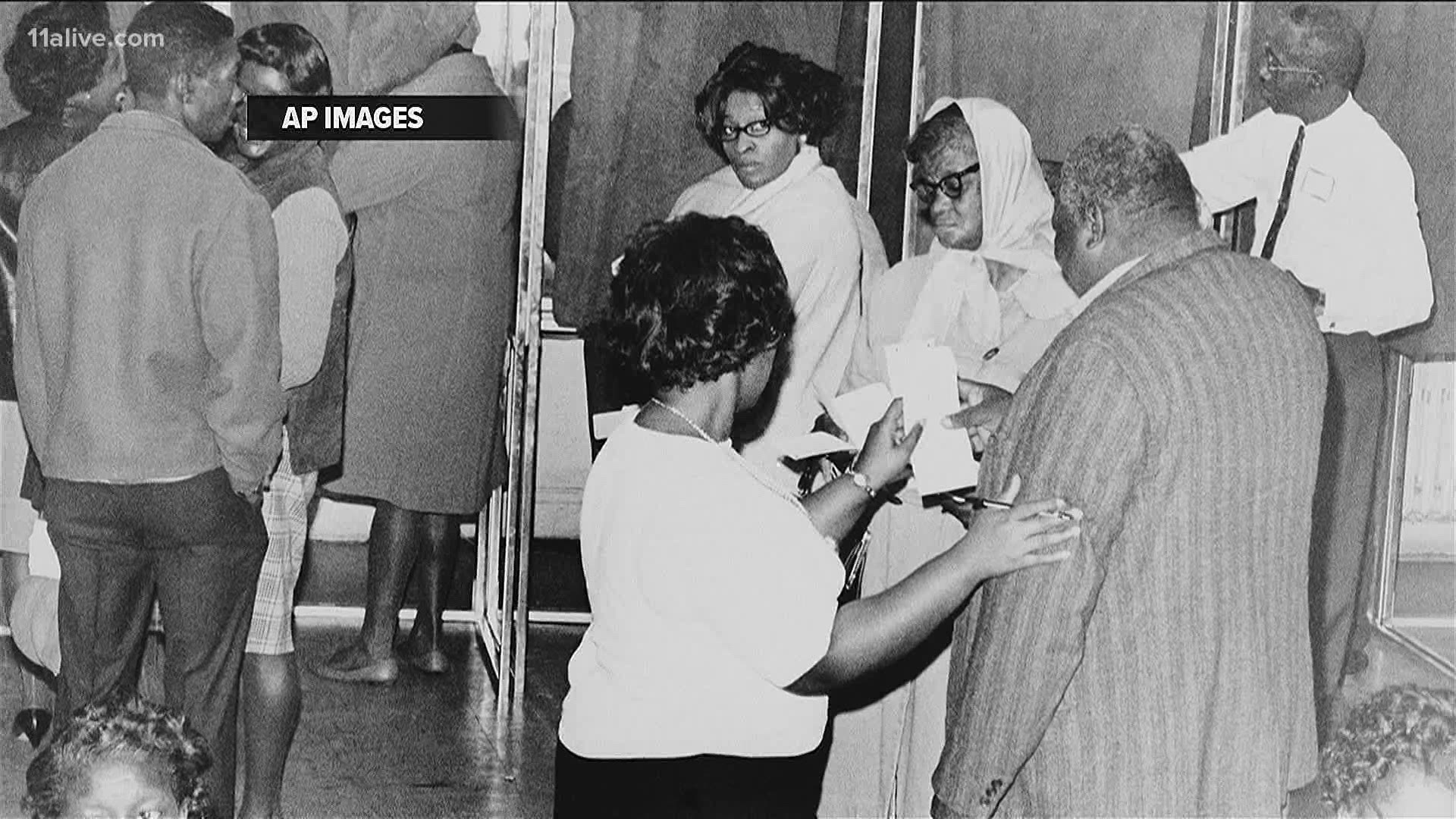

Georgia began using the runoff system in the 1960s after the Supreme Court knocked down the state’s county unit system. It was Georgia’s version of the Electoral College and gave a great deal of power to rural areas of the state.

Legislators from rural Georgia wanted a way for their voters to keep some of that power.

“There was a real rural vs Atlanta spirit in Georgia,” Kennesaw State University Political Science Professor Kerwin Swint said.

Legislators settled on the majority vote system.

The 1966 race for Governor complicated matters.

Although he finished first, Republican Bo Callaway didn’t get a majority of the vote in 1966. In those days, it was up to the state legislature to settle such matters.

“The legislature was overwhelmingly Democratic,” Dr. Charles Bullock, Political Science Professor at the University of Georgia explained. “So most Democrats voted for their fellow partisan and the Republican who got slightly more votes went home.”

That’s how segregationist Lester Maddox became Georgia’s governor.

Following that, the state instituted a runoff system for the Governor’s race and other statewide elections. It was the turbulent 60s, and some of the legislators who supported the change hoped it would weaken the black vote. Political scientists, however, say that’s not the primary reason the runoff system was approved.

“This is a way of introducing greater competition into that system, forcing people in the same party to compete with each other,” Emory University Political Science Professor Andra Gillespie stated.

While the law applies to most statewide elections, there’s an exception. Presidential candidates don’t need a majority of votes to win the state.