ATLANTA — Moviegoers will get a new look at one of the biggest stories in Atlanta history – the bombing at Centennial Olympic Park during the 1996 Olympics.

The movie, due out December 13, will focus on the man wrongly accused of the bombing – and the treatment he got from law enforcement and the news media.

Centennial Olympic Park was the largest gathering space of the 1996 Atlanta Olympics, and there were 50,000 people there after midnight July 27.

Beneath a bench, a security guard named Richard Jewell spotted an unattended backpack. A GBI agent opened it, and saw a bomb inside.The pipe bomb was filled with metal, nails and screws.

Two people died, and more than a hundred others were injured after it exploded.

Because Jewell spotted the backpack, he and other security staff had been able to move countless people away minutes before the explosion.

“But for that happening – just no telling how many people would have died,” said former U.S. Attorney Kent Alexander, who was part of the team investigating the bombing.

He and former Wall Street Journal reporter Kevin Salwen have written a book about it called “The Suspect."

For a day or so, the Jewell story was about a hero. He talked with CNN. He talked with local news.

“I just was at the right place at the right time, and did the job that I was trained to do,” Jewell told 11Alive afterward.

“In the morning, Richard Jewell was on Katie Couric (NBC’s “Today” show). And being tailed (simultaneously) by the FBI, unbeknownst to him,” Alexander said.

Jewell was a suspect. It was a well-kept secret, until Kathy Scruggs got the tip.

Scruggs was the Atlanta Journal-Constitution’s top police reporter – driven and well-respected. She was also blonde, flashy and sometimes flirtatious. She was a regular at Manuel’s Tavern, especially on nights Atlanta police were in attendance for off-duty drinks.

“She knew everybody in the police department, especially the homicide squad. And she could use the sizzle in her sexuality, in her personality. She was quick, she was witty, she was profane,” Salwen said.

The upcoming movie hints that Scruggs traded sexual intimacy with police sources for news tips. Alexander and Selwen say their research turned up no indication of that happening in the bombing story or any other story.

"She was a pro,” said Bert Roughton Jr., her editor at the AJC during the Olympics.

“She said you won’t believe what I’m hearing, that the security guard is the one who (police) are looking at,” Roughton recounted.

Scruggs confirmed the Jewell tip with another source. Another AJC reporter, Ron Martz, confirmed it with the FBI.

Roughton said he was uneasy publishing the information, but ultimately decided the newspaper had a duty to do it.

He knew the Olympics had drawn 10,000 or more reporters to Atlanta. The FBI’s interest in the heroic security guard was becoming less secret. It was a matter of time before other news outlets began to learn the information independently, Roughton said.

Asked if the AJC would have published Jewell’s name if he’d been just an anonymous security guard, Roughton said, “I don’t know the answer and I’ve thought about this a lot.”

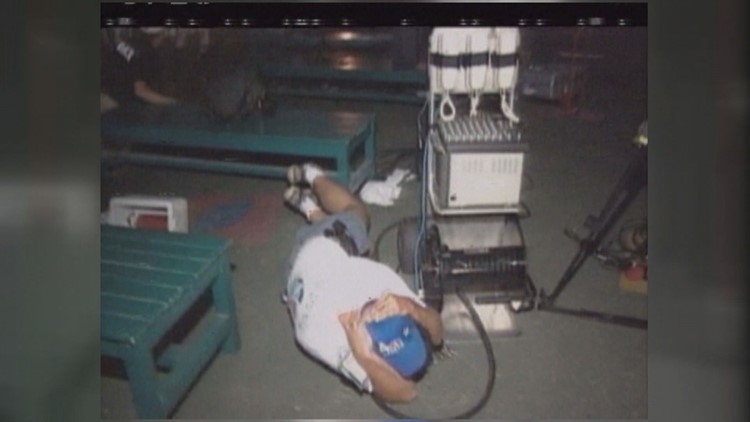

PHOTOS: 1996 Olympic bombing in Atlanta

“If he was an anonymous guard, his name and identity would have meant nothing to the story. That would have been a different set of circumstances,” Roughton said.

“They had the sourcing right. They knew that Richard was the lead suspect at the time, right wrong or otherwise,” Salwen said.

The AJC published it on the front page. And within a day, it was abundantly clear the story was solid.

FBI agents spent hours in plain sight at Jewell’s apartment on Buford Highway, hauling out bags of potential evidence – searching property in north Georgia where they thought he might have left behind clues about the bomb.

“It was legit that Richard Jewell was the lead suspect,” Salwen said. “Most of what was wrong was all of the material that came after, and ancillary. You had all of this kind of remarkable piling on of reporters who often knew nothing about the story.”

Coverage dwelled on unflattering profiles of Jewell as a southern rube, seeking attention as a cop-wannabe.

In the meantime, the FBI had released word of a call to 911 warning of the bomb – from a distant pay phone on Baker Street – raising serious doubt Jewell could have made the call.

Investigators slowly realized they had the wrong guy. But the damage to Jewell was permanent.

“I really do think Richard Jewell was a hero,” Roughton said. “A number of news outlets were sued - including us. Everybody settled except us. We continued litigating that for a long time. We felt that we had published an accurate story.”

Jewell got some recognition from then-Gov. Sonny Perdue. He got jobs in law enforcement, and died at age 44 of natural causes. State officials recently decided to put up a marker in his honor at Centennial Olympic Park.

Though Scruggs got the story right, her life was never the same either.

Scruggs also died young – at age 42 -- in 2001, following an overdose of prescription painkillers.

The fallout from the story was a “very hard thing for Kathy. And the lawsuits and tactics of Jewell’s attorneys were pretty aggressive and personal, with Kathy in particular,” Roughton said. “There’s no question in my mind Richard Jewell was the (primary) victim of all this stuff. And I feel bad about it for him. I also think Kathy was a victim.”

Her final story in the AJC was about the search for Eric Robert Rudolph – the man who later admitted he was the Olympic park bomber.

RELATED HEADLINES: