“Gone” tells the story of Mississippi native Felix Vail and the people whose paths he crossed. Vail goes on trial Aug. 8 in Lake Charles, Louisiana — the oldest prosecution of a serial-killer suspect in U.S. history. Vail is charged in the 1962 death of his first wife, and authorities suspect he is connected to the disappearances of two other women.

Did the wife of Felix Vail really drown?

Chapter 1: Something Awful

My office telephone rang, and a woman asked, “Would you be interested in writing about a serial killer living in Mississippi?”

“Yes, I would,” I replied.

The woman’s name was Mary Rose. She told me her missing daughter, Annette, had been married to a man named Felix Vail, and that Annette wasn’t the only one gone. She knew of two others.

TUNE IN: Watch a special edition of ABC’s 20/20 program featuring USA TODAY NETWORK and The (Jackson) Clarion-Ledger investigative reporter Jerry Mitchell discussing his role in the Felix Vail investigation and his reporting of "Gone". Tune in tonight at 10 ET/9 CT.

A day after Mother’s Day, May 14, 2012, I met the 64-year-old bright, short-haired woman and followed her to the property in Montpelier, Mississippi, where she planned to confront Vail.

She told me what she was going to say to him: “You may never go to jail, but I want you to know that I know and a lot of others know that you took the lives of these three women. You haven’t really gotten away with it.”

We parked and walked up to his gate, which was locked. She told me he lived down this path.

I followed her over the gate, and we walked down the path, the tall weeds blocking the light.

When we reached a clearing, we could see two trailers — a silver one gleaming in the sun and a second one 28 feet long and damaged.

I followed her to the silver trailer, where she knocked. No one answered.

She knocked again. No answer.

She checked the door. Locked.

Cupping her hands, she peeked inside and saw no one.

So where is this Felix Vail guy?

I turned around and noticed a patch of woods next to the trailers.

When I looked back, Rose was marching toward the damaged trailer. I hurried to catch up.

She checked the front door. Locked.

Circling the trailer, she noticed the back window was missing. She pulled the plastic off the window and slipped inside.

She opened the front door. Now I could see.

She rummaged through the trailer and began tossing things she found.

A machete clanked on the floor. Another machete clanked beside it. Then another. Then another.

Then a long sword clanked. Then another. Then another.

A chill ran up my spine, and I glanced back at the woods. Could he be watching us?

***

Felix Vail discovered he could disappear.

The blond-haired child stepped into the sandbox, where he liked to play on the family’s dairy farm in the community of Montpelier a half-hour north of Starkville, Mississippi.

He figured out that if he stood in the sandbox where a tree blocked his mother’s view, she couldn’t see him.

He would take one step back, then another, then another, slipping farther and farther away.

“She’d come and find me out there in the orchard 100 yards away,” he recalled in one of several recorded conversations he had with undercover private investigator Gina Frenzel. “I’d be fine or climbing one of the trees.”

He drifted off for hours at a time, and later, overnight.

He began testing other boundaries, tasting what he called the “nonsexual” parts of a girl in the neighborhood.

When his mother caught him and scolded him, he slid down the wall, crying. “I just crumbled,” he recalled. “I just wanted to die. It was the only time in my life.”

What upset him most was he couldn’t do it anymore. “It wasn’t a wrong thing until she was told it was wrong,” he said. “Damn ego, my mother. She totally polluted her son with ego and lies.”

At school, he excelled. In fifth grade, he made straight A’s, but five times the teacher noted he was “inclined to mischief.”

He also excelled on the farm. At age 16, he produced 130 bushels of corn in a 5-acre contest, topping every farmer in Clay County.

His father, Ray, gushed to the newspaper, “I thought my patch was good, but he beat me easily. His is the best I’ve ever seen.”

A year later, Vail volunteered for the military, hoping to be a pilot, and took a military aptitude exam. “I scored the highest score,” he recalled.

But the military found him unfit for military service. “They said,” he recalled, “I was not the kind of person who would follow orders and that I would be a disciplinary problem.”

Other signs of trouble arose. After his mother announced the family couldn’t keep their mother cat’s offspring, he scooped up the kittens and shot them, recalled his sister, Kaye Faulkner.

When a charismatic evangelist came to town, he became one of about a dozen teenagers who responded to an “altar call” at the Montpelier Baptist Church.

He told his family he believed he had been called by God to preach.

On the day he delivered his 10th sermon, he said he felt an “infinitely greater” power, which he compared to sticking his finger in a light socket. “I started getting electrical rushes and thrills and tingles and ... sweat popping out.”

He later wrote that he saw a “being” that day, “shimmering like a moon-sized sun with infinite energy radiating out from it in all directions at once.”

Suddenly, he said he knew the deepest thoughts of parishioners. “I knew who was screwing who.”

He never preached again.

By the time Felix Vail received his diploma from Montpelier High School in 1957, he was already working an enviable job at one of several plants surrounding the Cities Service (later known as CITGO) refinery in Sulphur, Louisiana — thanks to his favorite uncle, a supervisor there.

“I’m making lots of money,” he recalled. “I have two cars, a motorcycle and a boat. I’m dating about 20 women.”

Slender and 6 feet tall, he drove his Karmann Ghia convertible to nearby Lake Charles, where he hung out at the country club and strolled across the McNeese State College campus, searching for the prettiest women he could find.

“He told me he was an ordained minister,” recalled Cynthia Miller, a student then. “I asked, ‘Where’s your Bible?’ He said, ‘I don’t have it with me.’ ”

She said he took her to a McNeese football game and afterward asked her for sex. She turned him down.

“Suppose the world ends tomorrow,” he said. “You’ll never know.”

“Well,” she replied, “then I’ll never know.”

Some, however, took him up on his offer. “The majority of women were available to me just for the asking,” he recalled.

Many noticed his light blond hair and piercing blue eyes. “He looked,” one sorority member recalled, “like he had been kissed by heaven.”

***

Mary Horton was among those who noticed.

She had grown up in the Louisiana swamps, where Cajun food and music overflowed.

She became homecoming queen at Eunice High School, where she graduated and began attending McNeese State College. She was so popular that all five sororities invited her to join.

She chose Chi Omega, and her friends marveled at how, no matter what, she seemed to find the good in people.

Her cute figure and perky personality captivated many men, and the football team nominated her for the homecoming court.

“All of us horny men were secretly in love with her,” recalled Vail’s friend, Bob Hodges. “She was a doll, very sweet. I would have lifted that girl up on high.”

By 1960, she began to date Vail, who took her to company shrimp boils, where they stuffed themselves and danced the night away.

“I am so deliciously happy!” she wrote in one of many letters to a childhood friend. “Felix and I have been doing some really unusual things this week and having fun.”

They visited an African-American church, played 45s at Vail’s relatives, and ate at A&W Root Beer where they shared a lemonade.

But their relationship was not all bliss.

On June 20, 1960, Mary confided, “I really do love Felix, but I don’t think that I like him anymore. He really is sweet, but we don’t see eye to eye on things.”

She talked of being miserable with Vail and asked her friend to set her up on a date with someone else, hoping it might lead him to leave her.

“I never could break up with anyone,” she wrote. “I always keep hoping when there is no hope.”

In response to the date, Vail came to her and told her he was suffering from a disease.

“What disease?”

“Mary.”

She welcomed his words. “He did all the talking, and I just listened. I really had nothing to say — I mean, about us,” she wrote. “He said he’s changed. I have to.”

The couple dated again, and she continued to see others.

She joined classmate Kelley McFarland at a house party, and he later heard Vail was so angry he wanted to kill him.

McFarland tracked down Vail at a bar on Cities Service Highway near where he worked.

McFarland said he approached Vail, who responded, “I’d rather not talk about it here.”

The two men met in the dark woods. Although McFarland could sense Vail’s anger, no blows were exchanged, and the two men went their separate ways.

After this, Mary described herself as “miserable,” writing that “Kelley and Felix (were) threatening to kill one another.”

Vail remained jealous, she wrote. “Felix says that he doesn’t even want me to walk around the block with another boy now, and I know just what kind of miserable feelings he’s going through. It’s just tearing me up, and I can’t do anything.”

She reiterated her love for Vail in letters. “He’s going to move to Lake Charles next week, so he’ll be closer now.”

One night at a pool party in Lake Charles, Vail argued with Horton while her former boyfriend from high school, Leonard Matt, watched.

Vail “walked up to Mary and just slapped the heck out of her,” Matt recalled.

He wanted to retaliate, but others held him back.

Before fall ended, Vail told Mary he wouldn’t give her a Christmas gift because he didn’t believe in giving at designated times.

She planned to buy him something anyway, “even if it’s a lollipop,” she wrote her friend. “This is one thing I love, and it won’t change for me.”

When her friends questioned his refusal to give, she defended him, calling him a “wonderful person.”

In an Oct. 12, 1960, letter, Mary confided, “I say things that I don’t mean when I’m angry — like at Mom and Felix, for example, and I usually say the ugliest things to the ones that I love most because they are capable of hurting me the most. You always hurt the ones you love, the ones you shouldn’t hurt at all.”

***

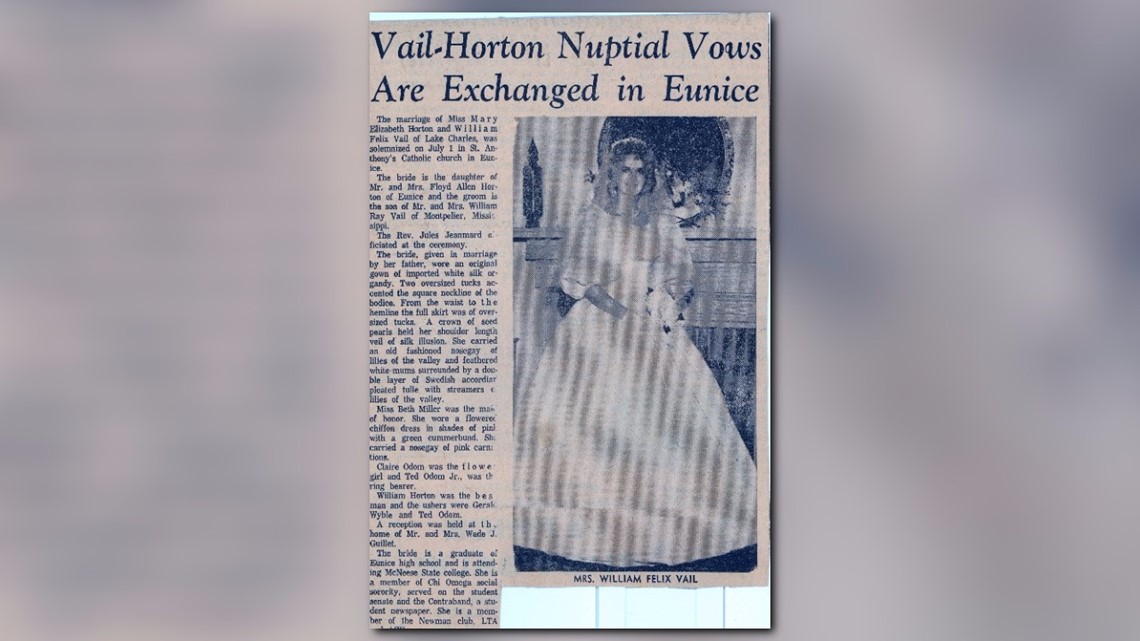

Felix Vail and Mary Horton married July 1, 1961, and that fall, she began her job as a second-grade teacher at Moss Bluff Elementary School.

Fellow teacher Myrtis Quinilty said she gave her a ride each day, and they decided to join a local gym together. “Felix did not want her to lose her figure.”

She said Mary later worried she might be pregnant because Vail didn’t want a child. A fellow teacher drove Mary to the doctor, where she learned the news.

“We had been so careful and still I got pregnant,” Mary wrote.

In February 1962, the couple traveled on a “second honeymoon” to Acapulco, Mexico, where they rode in a boat, soaked in the sun, ate lobster and listened to a band serenade them.

Back home, Vail worked the late-night shift and often stayed gone. When he returned, he talked about playing golf and bowling in leagues.

Mary wrote in a May 3, 1962, letter, “Felix hasn’t been acting so sweet earlier but I haven’t helped. I never stand up for him or say anything nice to him.”

Her sister-in-law, Sue, told her the only reason Vail believed Mary wanted to get married was to have a baby — not because of him.

After Mary heard this, she wrote her friend, “I can see, looking back, from many things I said how they could have been misunderstood.”

She insisted “we are very happy now,” but her sadness seeped through her letter, as she wrote about how unattractive she felt being pregnant.

She changed her hair color to a baby blonde. A month later, she tried silver blonde.

On the couple’s first anniversary, they greeted their baby, Bill, whom she adored and sang to.

Within a month, she suspected she might be pregnant again.

“My stomach has begun to get larger, and I don’t eat much,” she wrote. “It kind of excites me in a way.”

She talked of expanding her skirt. “Wonder if it’s not a tumor or something else. It hurts when you press my stomach on the right.”

Inside the Maree Apartments, where they lived, strange things began to happen. One morning, the couple awoke to find their front door had been removed from its hinges.

Another time, they found the front door on their apartment wide open. Nothing was missing.

Mary began receiving threatening calls.

“She was afraid,” Quinilty recalled. “Mary told me, ‘Felix and I decided it must be somebody watching because he only calls when he’s not here.’ ”

Despite her fear of drowning and of anything that crawled, Vail took her by boat into a wildlife reserve, where she saw an alligator sunning itself before slithering into the water.

When they spotted snakes curled up on the muddy bank, Vail blasted them with his shotgun. Dirt rained down.

He gunned the 40-horsepower motor, taking her way out into the Gulf of Mexico “until we couldn’t see the camps anymore,” she wrote, “and the water was so rough that I was a little scared.”

She heard “a funny creaking noise, and I just knew that the boat had sprung a leak because we had hit the waves so hard like at Acapulco.”

Vail bailed water, and they made it home.

She confessed to several Chi Omega sisters that her husband had done “something awful” in Mississippi. She wouldn’t say what.

She spoke with her mother about divorcing him, recalled her brother, Will Horton. Their mother, Lillie Mae Horton, a devout Catholic, urged her daughter to stay and work things out.

***

Darkness had long enveloped Shell Beach on Oct. 28, 1962, when Vail drove up in his boat at 7:30 p.m., saying his wife, Mary, had accidentally fallen into the Calcasieu River while they were laying trotlines.

After two days of searching, authorities recovered her body near the spot where he had told authorities she disappeared.

Her funeral followed the next day, Halloween.

Cynthia Miller, who had roomed at McNeese State with Mary, attended with her husband, wearing a black maternity dress.

When she walked up to Vail to share her condolences, he replied, “I’m sorry y’all couldn’t come to our party.”

“What party?”

“We called y’all, but y’all weren’t home.”

The words stunned her because “I never got a call from him,” she recalled. “My husband didn’t like him at all.”

The more she pondered, the more puzzled she grew. “What is he talking about a party at a funeral? Mary is dead.”

Four days after the funeral, deputies appeared at Vail’s work, arresting him. He refused to take a lie detector test.

The coroner ruled the death an “accidental drowning,” and Vail walked out of jail.

Alf Sanner. a fellow employee who believed Vail had killed Mary, pointed a finger in his face.

“Felix didn’t say a word,” Sanner recalled. “He just walked off.”

Months later, Vail picked up his son, Bill, from the Louisiana home of his wife’s aunt and headed for Mississippi.

Contact Jerry Mitchell at jmitchell@jackson.gannett.com or 601-961-7064. Follow him on Facebook and Twitter.