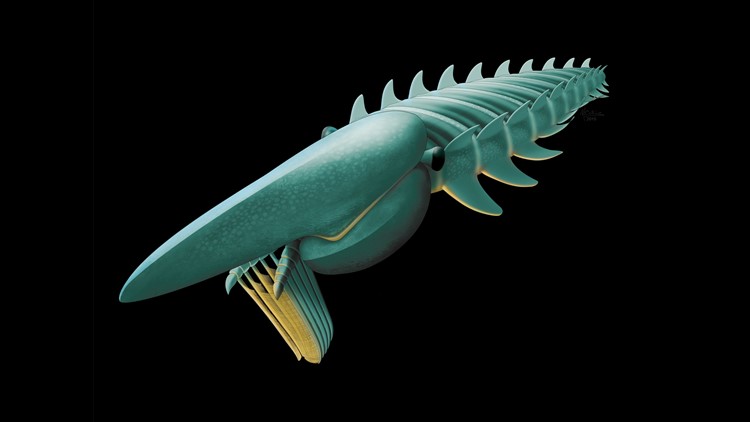

It looked something like a centipede, but without the legs. It had a protuberant snout like a swordfish and stubby swimming flaps. And it was longer than your coffee table.

At roughly seven feet in length, this now extinct monster of the prehistoric seas was bigger than any of its living relatives, which number in the millions of species. And it's not valuable just as an entry in the record books.

The new creature is a kind of arthropod, a group of animals including insects, crustaceans, arachnids and more obscure animals. No living arthropod is larger than the new sea monster, and only a few extinct arthropods – among them an amimal like a giant sea scorpion -- could claim to be bigger.

Scientists are hailing the seven-foot sea monster - which lived over 400 million years ago - for shedding new light on how insects and their kin came to be so diverse and so successful. But those same scientists can't help marveling at its size.

A large fossil of the new sea monster "weighs more than I do," says paleobiologist David Legg of Britain's Oxford University Museum of Natural History, who is not involved with the new study. When he saw it for himself, a researcher "dropped it on my arm. I've never been in so much pain."

"It would've freaked people out if they encountered it while they were swimming," says Yale University's Peter Van Roy, author of a study in this week's Nature describing the new animal. "But it would've been totally harmless," because, like some kinds of modern whales, it ate plankton. "It was a very peaceful, meek animal."

When bits and pieces of the new species began turning up in a fossil bed in Morocco in the late 2000s, Van Roy thought at first that the fragments looked like body parts of an anomalocaridid, a class of ancient sea creatures whose name means, roughly, "strange shrimp." But Van Roy rejected his hunch. The fossils, he thought, were just too big to be anomalocaridids.

But as more fossils came to light, it became clear that the pieces did indeed belong to a huge new species of anomalocaridid that lived some 480 million yeas ago. Slung below its flamboyant helmet was a structure akin to a mesh basket, which it used to catch meals of plankton.

The basket's bristles may have acted like the baleen of modern-day whales, says evolutionary biologist Georg Mayer of the University of Leipzig, who was not involved with the study.

Other anomalocaridids were known as fierce predators, but this Moroccan swimmer seems to have evolved a more peaceable lifestyle, thanks to the rich plankton stocks of its day. Along the way, it became, on the evidence of one stunningly complete fossil, "ridiculously large," says zoologist Joachim Haug of Germany's Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich, who was not part of the research. The easy availability of its chosen food may have allowed it to swell to its enormous size, which may have deterred predators.

Running down its sides, the new anomalocaridid had two rows of flaps that would've helped it steer, breathe and propel itself forward. It's those flaps that catch the interest of researchers studying arthropods, the vast family of creatures that includes everything from crabs to insects to millipedes.

Though wildly diverse, all have a few traits in common, such as a segmented body and many pairs of limbs. Anomalocaridids were a very ancient form of arthropod.

One of the key structures found in early arthropods was a limb with two separate branches. Over time, evolution transformed that basic limb into many different clever designs, helping give rise to the mind-boggling variety of arthropods alive today. Anomalocaridids were also early arthropods. But there was no evidence that they had those characteristic two-branched limbs.

The two rows of flaps on the new sea monster are an ocean-going animal's version of two-branched limbs, Van Roy says. That means that anomalocaridids "represent a very, very early stage in arthropod evolution," he says, paving the way for the millions of arthropod species that now dominate our earth.

Anomalocaridids are "cool," Haug says. "They deserve the publicity they get."

PHOTOS | Fascinating new scientific discoveries