Lines, polling changes and voter frustration | The impact of Georgia elections

The series looks at how voting and elections effect Georgians across the state.

On the first day of early voting in Georgia, some polling locations experienced wait times upwards of three to eight hours, prompting boards of elections to release duration maps online.

This isn't the first time the state has been highlighted for various election problems.

11Alive takes a deeper look at a common thread tying two Georgians together and how changes in the state have impacted voters.

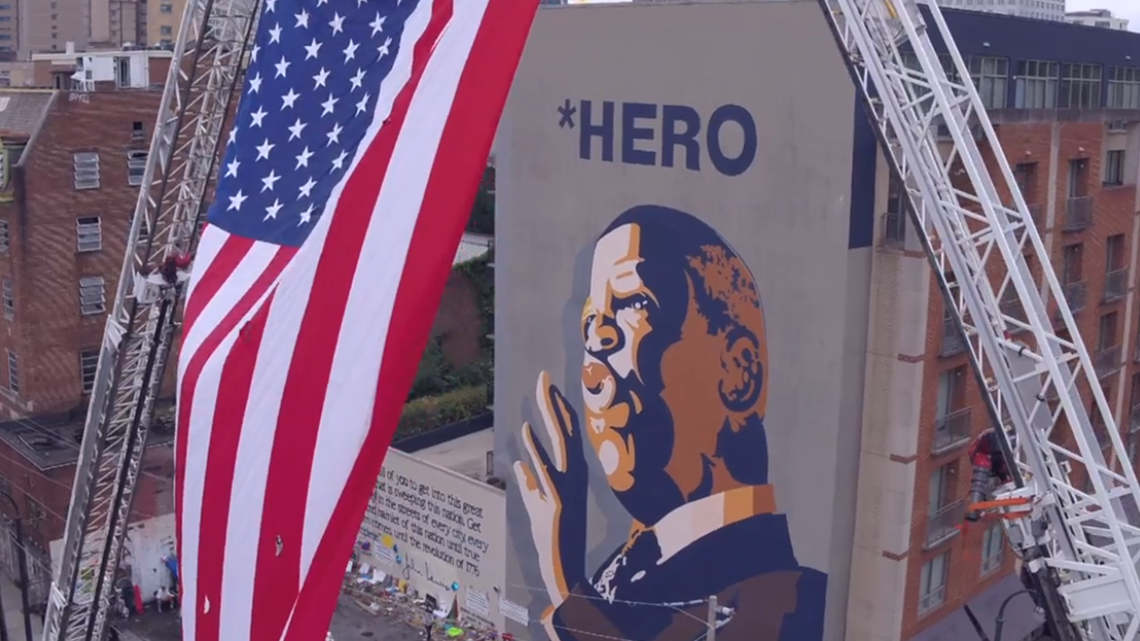

"I don't think his work is done" Georgia voters talk about their voting experiences and the legacy of John Lewis

A mural of Rep. John Lewis now watches over Auburn Avenue in downtown Atlanta. But 55 years ago, on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, Lewis was marching, leading the protests that would change America forever.

Despite the backlash and beatings he endured, Lewis would dedicate his life to the fight for equality -- and the right to vote.

“My dear friends: Your vote is precious, almost sacred. It is the most powerful nonviolent tool we have to create a more perfect union,” Lewis said in a 2012 speech in Charlotte, North Carolina.

In 1965 — the same year Lewis marched in Selma — The Voter Rights Act was passed under President Lyndon B. Johnson.

Its purpose was to prevent discriminatory laws from being used against non-white voters, especially in southern states, like Georgia.

“Our ancestors died. There are people who died so we could have this right,” a 72-year-old former bishop in Atlanta said about equal voting rights.

“I take [voting] more as a duty. It’s something that people before me fought for, so everyone could have that right,” a 39-year-old voter said about the significance of voting in his life today.

Both men come from different backgrounds. They were born into different generations, have different life experiences, live in different neighborhoods, and have never met each other.

There is, however, one common thread tying all three men together -- a faint echo of unequal voting experiences compared to others.

Their names are John H. Lewis and John Lewis Jr.

Georgia - a case study:

For years, election mishaps have been well-documented throughout the country but Georgia is a state that stands out from the rest.

Georgia repeatedly makes headlines for long-wait times at polling locations, mass voter purges, displacement of voters at polling locations due to last-minute changes, and more.

“They removed machines, so the lines became longer, and of course, the wait times as well,” John Lewis Jr. said of his own voting experiences in Georgia. “So that discouraged a lot of people but I felt that was my duty, so I always stuck it out.”

At the beginning of September, the Georgia Secretary of State's Office announced more than 7 million active voters are eligible to participate in this election. That is nearly 2-million more active voters recorded between the 2008 and 2016 general elections and more than 3.5 million compared to 20 years ago.

Fulton, Cobb, Gwinnett, and Dekalb -- metro Atlanta’s four major counties -- list 2.4 million active voters this year.

“Georgia is one of the easiest [places] to get registered because we have automatic voter registration. So, almost 90 percent of eligible voters are registered to vote,” said Georgia Secretary of State Voting System Implementation Manager, Gabriel Sterling. “So we have a record amount, we have nearly two million more people on the rolls in 2020 versus 2016.”

On the first day of early voting for the 2020 general election, some polling areas experienced wait times upwards of three to eight hours, prompting several county boards of election to release duration maps online.

“The lines - they remain long,” John Lewis Jr. said of the wait-times this election cycle.

Four months earlier, floods of Georgia voters found themselves stuck waiting in long lines to cast a ballot in the primary.

Park Tavern in Midtown turned into a mess.

“Park Tavern was 100 percent driven by COVID but it was also exacerbated by Fulton County decisions because they had multiple locations they put into one particular polling place,” Sterling told 11Alive.

“When Fulton made those decisions, it was done because they lost 45 polling locations due to COVID and every county had to face those kinds of obstacles in June, which now they’ve done a really hard job of adding more polling locations both early and election day,” he added.

Still, some experts are concerned that Georgia’s election woes could worsen.

“These issues the Secretary of State's office has known about for some time, and instead of effectively addressing them, what we're hearing instead is rhetoric that doesn't match reality,” said Aklima Khondoker of the non-partisan group of All Voting is Local.

“What we’re hearing, instead, is all the technological issues are addressed. Everything is fine. That simply isn’t true. We’re also hearing the lines are down. There are no lines. That also simply isn’t true.”

In the final days of early voting, Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger told voters to prepare for longer waits.

“We expect even more higher turnout than we’ve seen so far,” Raffensperger said during an Oct. 26 press conference. “With that, there may be lines. Expect lines, long lines.”

Despite the Secretary Of State’s office being the leading election oversight in Georgia, what voting day looks like for people largely boils down to individual decisions made by counties explained Sterling in his interview with 11Alive.

Khondoker says the “who-done-it” shifts in responsibility between county boards and the state blurs any opportunity to find and fix root causes of Georgia’s election issues.

“The more difficult it's to figure out -- who the responsibility lies with -- the more difficult it is to have accountability to actually address these issues,” she said.

'Perhaps we were not where we thought we were'

In 2013, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled 5 to 4 in the landmark voting rights case Shelby v. Holder. Ultimately, the decision rolled back Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act, which specifically required all states, particularly those in the south, to notify the Department of Justice before making changes to any of their voting laws and procedures.

In her dissent, the late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg famously wrote, “Throwing out preclearance when it has worked and is continuing to work to stop discriminatory changes is like throwing away your umbrella in a rainstorm because you are not getting wet.”

Voting rights advocates site that 2013 decision as a key factor for vastly different voting experiences by Black and other non-white individuals over the past 7 years.

“We're so accustomed to hearing that there's so many advocates that are fighting for our voting rights in this state and nationwide, but we forget that we have this device in place,” Khondoker said. “We have protections through the Voting Rights Act so that people do not disenfranchise Black and Brown voters who have not historically had equal access to the ballot.”

After the 2013 ruling, an analysis by the Leadership Conference Education Fund found that states had shortened voting hours and days, purged eligible voters from rolls, implemented strict voter identification laws, and more.

“Ridiculous things like the number of bubbles in a bar of soap,” John H. Lewis said of problematic poll requirements for Black voters prior to VRA. “That’s real. Those are not stories that somebody just came up with. Those things actually happened.”

Several states implemented new requirements after the roll-back of Section 5 of VRA in 2013. Georgia opted for more stringent voter ID laws and closing polling locations.

According to the Leadership Conference’s report, 1,600 polling locations were eliminated around the country from 2012 to 2018 and at least 214 of them were in Georgia.

“You can’t have a functional democracy if people can’t access the ballot. The point of having an effective elections administration is to make sure that more people can cast their ballots and not less,” Khondoker said.

Black Georgians make up around 32-percent of the state’s total population. Of the more than 7 million active voters listed in SOS data year, 30 percent were recorded as Black, non-Hispanic individuals.

“I walk but it’s quite a trek for me to walk that distance, to vote. I can take my time and do it but it would be much more convenient if the polls were in walking distance as they once were,” John H. Lewis said of voting polling location changes in Atlanta.

“Perhaps we were not where we thought we were,” the 72-year-old added during his interview.

Data obtained by 11Alive from county boards of elections show Fulton, Cobb, Gwinnett and Dekalb -- areas where both John Lewis’ live and that all account for a large, consolidated portion of Black Georgia voters in 2020 -- have had noticeable fluctuations in polling precincts, especially before and after Shelby V. Holder.

Georgia was still changing and assigning polling locations as recently as September.

“Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the county lost many polling places before the June Primary, which had just 164 locations. These changes will directly affect thousands of voters and because of the large number of location changes, Fulton County will be sending notices to voters by mail to inform them of the changes,” the county board of election stated on its website in September.

Changes to polling precincts and locations raise questions about what level of impact it has on voters in the communities they serve.

“Whenever a polling place location that used to be conveniently located is no longer there. That is that much greater cost to the voter” Khondoker said.

'What difference will my one vote make?'

“What difference will my one vote make? It makes all the difference in the world,” John H. Lewis said.

“This one vote could change the lives of our children, our grandchildren,” John Lewis Jr. said.

Georgia voters from all backgrounds and walks of life continue to set records days before November 3rd. As of October 27th, more than 3.1 million Georgia votes had been cast, either through early, in-person voting, or through mail-in-ballots.

This year, John Lewis Jr’s son turned 18-years-old and among those new voters.

“I think it’s important for everyone of all colors and creeds to take that duty and voice their opinion,” he said.

As for the man who paid for their right to vote with his own blood 55 years ago, both Lewis’ say there’s still much to do moving forward.

“John Lewis is gone but is his work finished?” 11Alive Chief Investigator Brendan Keefe asked.

“No. I don’t think his work is done yet,” 39-year-old John Lewis Jr. said.

The 72-year-old retired Bishop John Lewis offers a similar sentiment.

“We’ve accomplished much but there is much more that has to be done.”

Tale of two votes: election changes impact non-white voters

Georgia's early voting locations opened on Oct. 12 and people arrived in droves.

Millions who could vote in-person, despite the novel coronavirus, did. While many voters breezed in and out, others reported painstakingly long lines.

“This is a system that’s broken. It needs to be fixed. It definitely feels like voter suppression is going on here, with the hope that people will just get frustrated and walk away,” a woman named Denise told 11Alive after waiting eight hours to vote in Gwinnett County.

“The record number turnout… has slowed down processing for some voters,” Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger said during an Oct. 26 press conference.

“There has never been easier voting in Georgia,” he added. “My job at this office is to ensure all Georgians that there is neither rampant vote theft or suppression. People have concerns and I get it.”

'The system is a joke. And we’re not laughing'

During the hotly contested Bush vs. Gore race in 2000, an estimated four to six million votes were not counted.

According to the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, those ballots disproportionately belonged to non-white voters.

Yet two decades later, tales of vastly different voting experiences still reverberate through Georgia.

“Fifty-three years I’ve been voting. I’ve never seen a line like this in 53 years,” said J.O. Wade outside a southeast Atlanta precinct during the June primary.

“I’ve been in line since almost six this morning. It’s almost nine and I haven’t moved at all,” Simone Hannah told 11Alive as she waited in the Georgia summer sun.

“The system is a joke. And we’re not laughing. I know I’m not,” voter Darlene Poole said.

Dr. Charles Stewart III, a political science professor and current director of the Cal-Tech/ MIT Voting Technology Program, studies election problems, and voter wait times.

He explains that voter roadblocks are fueled by the rise in demand to vote, the strain on election resources, and polling location changes.

“It seems to me, in observing and talking to officials, that there are pressures to expand convenience to voters but there are also real pressures to economize in running elections and I think that’s the tension here oftentimes -- especially in states like Georgia that are buying machines in a time of fiscal austerity, trying to get as much possible out of the machines,” he said. “I think that in many places, it may be that more machines need to be deployed in order to deal with that demand.”

After the Voting Rights Act of 1965, the number of Black individuals registered to vote in Georgia, Alabama, and Louisiana more than doubled, according to the Center for American Progress.

In 2020, those numbers are on the rise again.

According to the Pew Research Center, the number of Black eligible voters grew slightly between 2000 and 2018. Georgia, Delaware, and Mississippi saw the largest increases in the nation.

As of early September 2020, there were more than two million Black active voters in Georgia.

However, despite this growing number of diverse voters, polling locations and precincts have dwindled.

“The sort of consolidation of polling places that we see in Georgia and actually in many other states, primarily in the Sunbelt, is the sort that's likely to add barriers to communities of color,” Stewart said. “Even if it, at the end of the day, doesn’t drive turnout, because it increases the cost of getting to the polling place.”

'The way the system is set up is not set up for voters'

After a 2013 landmark Supreme Court decision reversed Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act, about 1,600 polling locations closed across the country and over 200 of them were in Georgia, according to an analysis by the Leadership Conference Education Fund. In the 7 years since the Shelby vs. Holder decision, the impact is becoming more pronounced.

“I remember in the elections division, there were file drawers full of the preclearance forms that the State of Georgia had to file every time there was a change in any election procedure in the state. And the most common one had to do with the movement -- the moving of precincts,” MIT’s Stewart said, recalling his time as an intern at the Department of State “I mean, even just a move across the street would have to be analyzed and reported to the Department of Justice. So, it was quite a thorough regime before the Shelby County decision.”

Since 2013 Georgia has the distinction of closing “higher percentages of voting locations than any other state.”

“The way that the system is set up is not set up for voters. It’s set up to shirk responsibility and it's set up to have less and less sites available for people to access. That’s how the whole structure is set up and that is not good for voters,” said Aklima Khondoker of the non-partisan group of All Voting is Local. “That cannot be the way that we continue with our elections in Georgia. It’s harmful for voters”

The top three counties for closures in Georgia, according to the analysis, were Lumpkin, Stephens, and Warren. Seven of the counties with major polling place reductions in the state ended up with one polling site to serve hundreds of square miles

In 2015, then Georgia Secretary of State Brian Kemp sent out a memo encouraging counties to consolidate voting locations.

“When should you begin the plan of consolidation or making changes to precincts or polling Places?” the 2015 memo reads. “Now. Plan to spend 2015 making all of the changes so that you, your county, and your voters are ready for the 2016 elections."

An independent data analysis by 11Alive -- focusing on Fulton, Gwinnett, and Dekalb found noticeable differences in the number of polling precincts available before Shelby V. Holder. Those same four counties account for nearly 50 percent of all Black active voters in Georgia this year.

Those changes concern voting rights advocates.

“If you don't know that your polling site has changed and you show up and you've only allotted that hour to get that done then to get back to work. Now you're disenfranchised because you weren't expecting that you didn't know that your polling site would be closed, you didn't know where you had to get that updated information,” Khondoker said.

“When you move that polling place away from somebody, they become less likely to vote. In fact, you can put a number on that. You move a polling place a quarter of a mile away from the voter and they become one percentage point less likely to vote,” Stewart said.

FULTON COUNTY

- 2008 = Was not able to locate or provide to 11Alive by deadline.

- 2012 = 351 polling precincts

- 2016 = 346 polling precincts

- 2020 = 395 polling precincts

DEKALB COUNTY

- 2008 = 194 polling precincts

- 2012 = 189 polling precincts

- 2016 = 189 polling precincts

- 2020 = 191 polling precincts

COBB COUNTY

- 2008 = 177 polling precincts

- 2012 = 153 polling precincts

- 2016 = 144 polling precincts

- 2020 = 145 polling precincts

GWINNETT COUNTY

- 2008 = Board of Elections told 11Alive they don’t maintain records this far back.

- 2012 = Board of Elections told 11Alive they don’t maintain records this far back.

- 2016 = 156 polling precincts.

- 2020 = 156 polling precincts. Also said that the county, “Lost one of the polling locations and have merged that precinct into another polling location. That location will house two precincts on Election Day.”

But it’s not just the number of locations changing. It’s also the number of voters those precincts are assigned to serve.

“We have millions more voters since Shelby v holder. But statistically, we've got fewer polling places. Is that accurate?” 11Alive’s Chief Investigator, Brendan Keefe, asked the Secretary of State's voting system implementation manager, Gabriel Sterling, during an October 2020 interview.

“That is, that is accurate and those are county-level decisions. In some counties, it makes sense. Because, take Lumpkin County, for instance, they've collapsed down to a single polling location because they found the best thing for their voters,” he responded.

The cost of casting a vote

For years, experts have pointed towards key differences in voter experiences.

A study by the Bipartisan Policy Center and MIT highlighted Georgia for having 2.6-times the national voter wait-time average in 2018.

Another analysis by the Brennan Center for Justice found Black voters waited for an average of 45 percent longer than white voters. The polls in counties with fewer electoral resources -- less polling places, voting machines, and poll workers -- had longer wait times in 2018.

“Voters in these communities get harmed coming and going. Because it's, you know, perennially underserved and disadvantaged especially in times of crisis, and then the vote itself may be the only or the most effective mechanism to overcome these disparities. And there will be even greater frustrations when it's harder to vote. The polling places have been closed, voting machines aren’t there, poll workers don't show up, etcetera,” Stewart said.

While other surveys show Black and Hispanic-Latino individuals have more difficulty locating polling locations compared to white voters, there are several other factors that can feed into unequal voting opportunities.

“Not everybody has the same level of access. So it's not necessarily a choice that people are making, saying that it's not worth my time. I think the real issue is that for black and brown voters who may have to work hourly jobs, who may have to work two and three jobs,” Khondoker told 11Alive.

The United States is only one of a few countries that still hold Election Day during the week and it isn’t a federal holiday. While some states do allow time off for employees, it largely varies state-by-state and it’s often up to employees to request it.

This can be a crippling choice for those who have to make a decision between voting or their job.

“It’s not a matter of they’re not willing to do this, or that they’re incapable of having a fighting spirit to push further,” Khondoker told 11Alive. “It’s that they are fighting for their lives. They need to work. They need to take care of their children. They can’t fit in this extra distance to vote when they also have to go to the grocery store. When they also have other things to do.”

There are also other factors that can make the process challenging, like complicated provisional ballots and requirements to present government-issued identification cards.

“There tends to be a disproportionate effect on communities of color, and other underserved communities as well, which I think is pretty easily tied, not even necessarily to racism but, you know, the types of public service inequalities that we see throughout state and local government,” Stewart said. “Black and brown communities tend to have, you know, worse roads worse sidewalks, worse schools and so in a sense not surprising that they would also have less access to in-person voting as a consequence of imbalances in political power.”

Record-breaking turnout

Georgia easily broke several voting records even before Election Day 2020.

As of Nov. 1, the state recorded more than 3.9 million total votes cast. Of that, more than 2.6 million votes were from in-person, and more than a million had been from absentee ballots.

While white Georgia voters make up the majority of early ballots, Georgia Black voters make up over 26 percent of those who’ve already visited the polls.

The Secretary of State’s office estimates Georgia’s total number of votes could leap to five million by the time the close of polls on Tuesday.

“No one ever thought we were gonna have four million votes before election day,” Sterling told 11Alive during his interview.

Khondoker reminds everyone to make sure their choices count.

“Please vote. Your voice matters. Your voice matters and the State of Georgia needs your vote. So please vote,” she said.