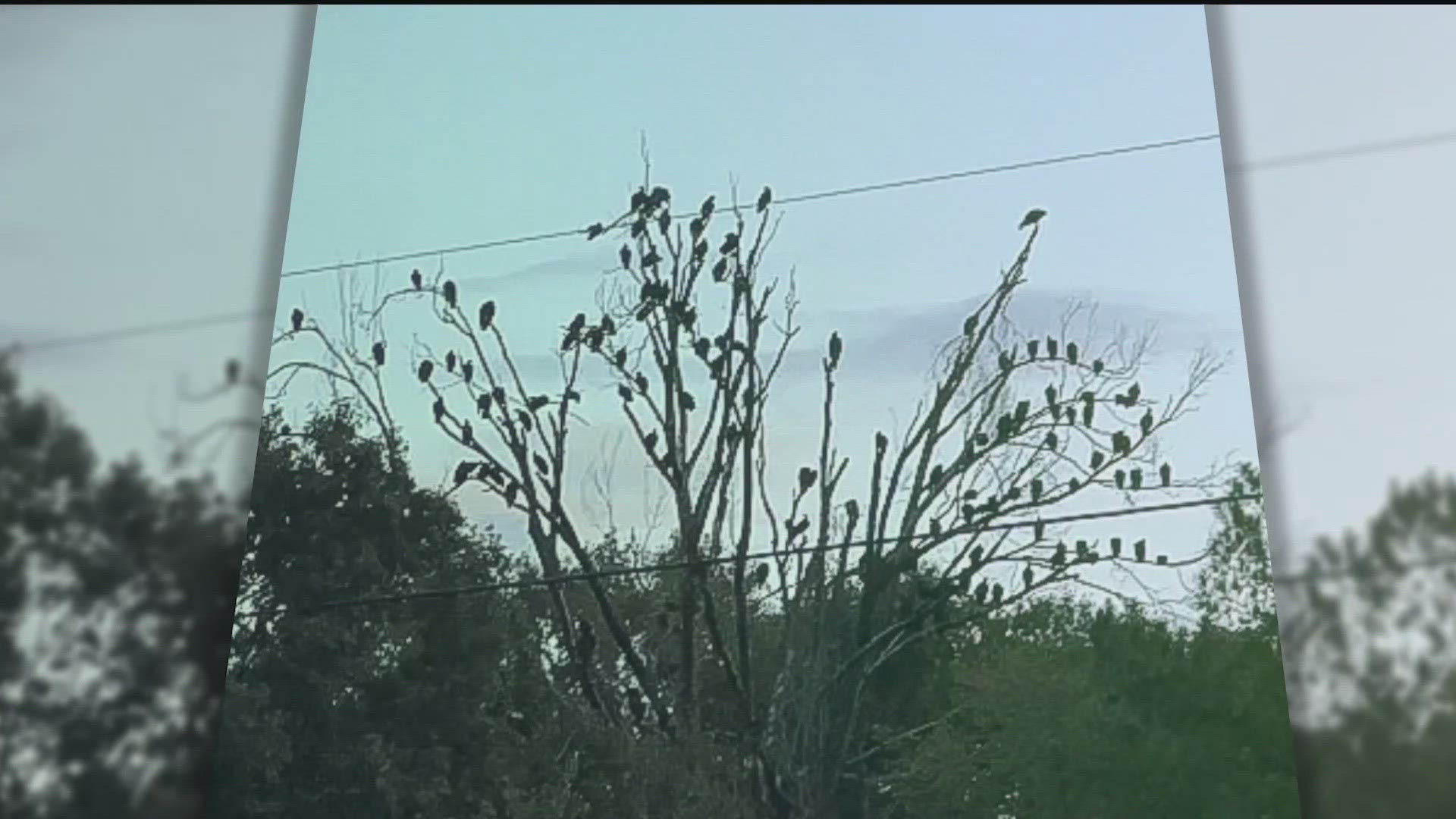

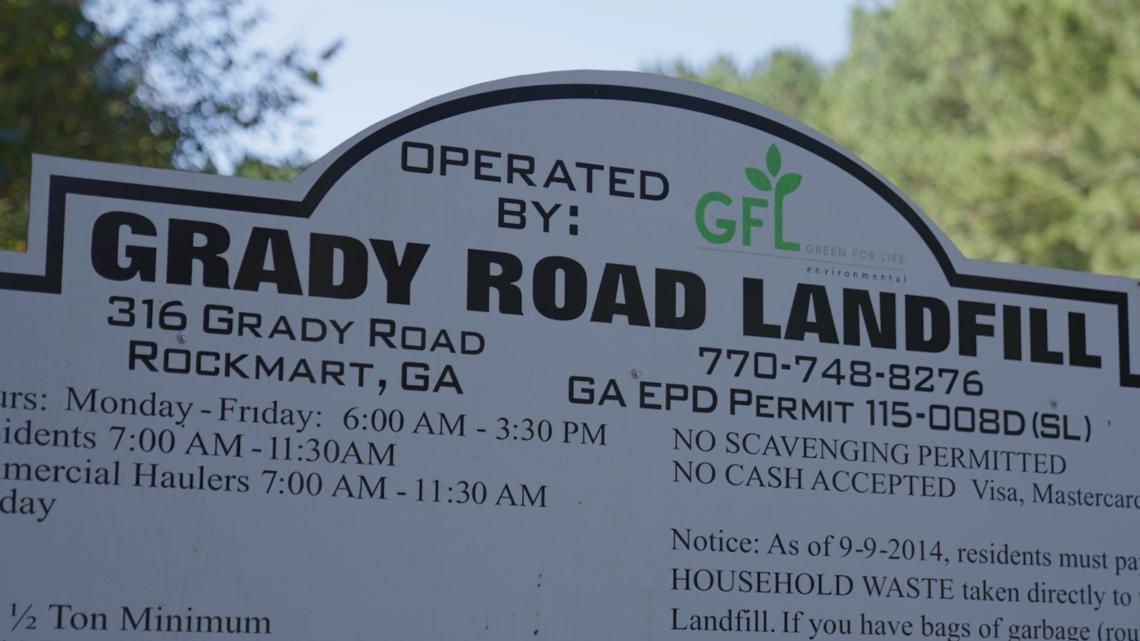

POLK COUNTY, Ga. — Hundreds of vultures have taken over the front yards of residents living near the Grady Road Landfill in Polk County. For homeowners like Hansley Davenport, the situation has become a daily nightmare.

“It’s terrifying,” Davenport said, describing the birds that roost in the trees surrounding her home. “It looks like something out of a horror story.”

While the vultures have grabbed attention with their unsettling presence, Davenport and her neighbors say the real problem is the growing landfill just behind their homes. Known locally as “Mount Trashmore,” the site has become a contentious issue for residents who are concerned about the environmental and health impacts of the expanding trash dump.

Concerns pile up

Davenport’s family has lived on Grady Road since the early 1900s. She has watched the area change over the decades, but the landfill’s presence has only grown larger—and louder—over the years. The landfill, which has been operating since the 1990s, now accepts trash from outside Polk County, drawing in waste from neighboring regions like Douglas and Fulton counties. This influx of trash, Davenport argues, is exacerbating the problems facing the community.

Polk County's vulture invasion

For Davenport, the most alarming consequence of the landfill’s proximity is the swarming vultures. She describes how hundreds of the birds gather daily in the trees and on rooftops of homes around the landfill.

“It's like a scene out of a horror movie,” Davenport said. “They perch on your roof and tear up everything. Their talons can damage your roof, and their droppings and vomit are acidic enough to melt it.”

The vultures are not just a nuisance; they pose a real danger. Their acidic droppings can damage shingles and the rubber materials on roofs, while their presence in the area increases the risk of disease transmission.

At one nearby church, Davenport pointed to the roof, covered with feathers and droppings.

"It’s just poop and feathers up there," she said.

A stinky crisis

While the vultures are a pressing concern, residents like Davenport are also frustrated by the constant stream of trash trucks coming in and out of the landfill. According to Davenport, the trucks are noisy, smelly, and frequently carry waste from other counties, including Fulton County and neighboring Douglas County.

Data shows that more than 20% of the landfill’s waste comes from Fulton County, with another 40% from Douglas County, while less than 10% originates from Polk County itself.

“I want the trash to stop coming from other areas,” Davenport said. “The damage has already been done, but adding to it makes it worse. We need to cut ties with this landfill.”

Local and state response

Polk County officials are aware of the concerns, but local leaders say it’s out of their hands. While the county owns the Grady Road Landfill, it contracts with GFL Environmental to operate the site, and it is GFL that handles day-to-day operations and any issues related to the vultures.

“The county is aware of the complaints, but it is up to the landfill operator to address the vulture problem,” said Polk County Manager David M. Rose.

However, Davenport and other residents argue that this issue goes beyond just the county—it’s a problem faced by many communities near landfills in Georgia. According to state data, nearly 40,000 people live within one mile of a landfill, many of whom face similar environmental challenges.

“I’m not the only one going through this,” Davenport said. “There are thousands of people living with this problem, and we need action from lawmakers.”

Where will the waste go?

The Grady Road Landfill is expected to close 10 years earlier than planned, with projections now showing it will close by 2030. It was originally slated to shut down in 2040.

This raises concerns about where the region’s growing waste problem will be directed once the landfill reaches capacity.

With Polk County already dealing with the environmental fallout of the landfill, residents are anxious about what will happen to the trash—and the vultures—once the site closes.

“We need better waste management practices in this state,” Davenport said. “The vultures are just a symptom of a bigger issue. If we don’t address this now, it will just keep getting worse.”