Georgia jury finds parents guilty of child abuse. They maintain there's a medical reason for son's injuries

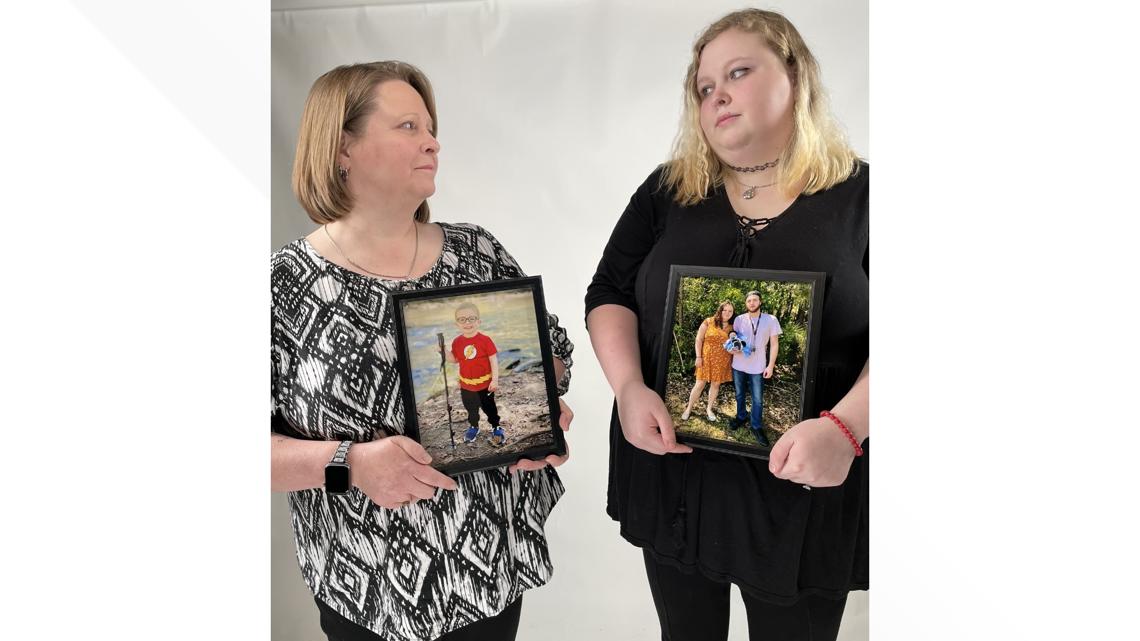

Tarilyn and Tyler Alexander's sons were taken away from them after they took their oldest to the hospital to get to the bottom of his unexplained injuries.

Tracie and Johnnie Lester’s children were one by one, growing up and moving out of the house. The couple had started to discuss what retirement might look like.

“We were finally at the point where we didn’t have to hire a babysitter, and we could leave the youngest one here,” said Tracie Lester.

But sitting in a playroom packed with toys, it was clear retirement would have to wait. She now had two new young boys giggling as they picked through the bins of musical instruments, stuffed animals, and cars looking for just the right one.

As they played, the phone rang. It was their mother, Tarilyn, calling from prison.

Three years ago, Tarilyn and her husband Tyler Alexander were accused of abusing their first-born Parker, who at the time was 8 weeks old.

Shortly after, the Lesters got custody of the boys to keep them out of foster care while the parents fought the accusations.

The couple believed so strongly they’d reunify that as the jury took a break from their deliberations at the Pike County courthouse, they were down the street child-proofing their boys’ bedroom. After all, their sons both left as infants but would return as toddlers.

But the jury was not convinced.

While two of the charges were thrown out during the trial due to conflicting evidence, the jury found the couple guilty of 12 of the remaining charges.

Questioning injuries

No one disputes Parker had several broken and fractured bones, but his parents insist they never treated him aggressively. They believe their son suffered from a complex series of medical events that unknowingly left him with weaker bones.

Attorneys for the parents noted both Parker and Tarilyn’s low vitamin D levels and the fact he was born 5 weeks premature, having marginal cord insertion, a rare condition that can slow the baby’s growth. Parker spent the first 10 days in the NICU, seven of those on a respirator.

They were back at the doctor’s office shortly after Parker’s release with concerns about excessive regurgitation, or GERD, and he started to have small bruises or red marks pop up and then disappear for no obvious reason.

It wasn’t until his parents noticed his right leg was severely swollen that doctors grew concerned. A scan of his body showed a broken right femur, a fractured tibia, a wrist, and three broken ribs, all in various stages of healing.

The parents were told to leave the hospital. They haven’t seen Parker since. Shortly after Reid was born, the state put him in protective custody as well due to their bond conditions.

11Alive's investigation Help that Harms isn’t as much about parent guilt or innocence as it is about the systemic roadblocks that make it tough for families to quickly get an independent second medical opinion and maintain a close relationship with their child without having to go deep into debt.

“Our system is based on people having faith in the justice system. So, if we can do everything we can to make sure that we get the answer right, even for this small group of people, then people will have more faith and more confidence in the larger system,” said Georgia's former Division of Family & Children Services director Tom Rawlings.

There are parents guilty of horrendous crimes. In 2023, Child Welfare Data released by DFCS, says the division fielded 60,644 safety concerns. A small number of those children, 418, were involved in allegations of physical abuse.

Last year’s data doesn’t break cases down by age, but in previous years, about 18 percent of those were infants, children who had yet to celebrate their first birthday.

“Physical abuse is fortunately not very common. Neglect is the biggest issue we deal with,” said Rawlings.

Using child abuse pediatricians

Rawlings now works as an attorney but has also run the state’s child advocacy office, and he’s served as a juvenile court judge. He has seen the challenges of identifying and stopping abuse from more angles than most.

He is grateful Georgia has five child abuse pediatricians working at area hospitals to help identify injuries related to physical abuse, but also sexual abuse and neglect.

“They really are a wonderful first line of defense to make sure that children who have been abused are receiving proper safety and are getting cared for,” said Rawlings.

It is a child abuse pediatrician, or CAP, who diagnosed each of the babies at the center of 11Alive's investigation, Help that Harms. Rawlings said as an attorney he has also represented parents he believes are innocent.

“So to me, the question is not dismissing the great work of child abuse pediatricians, but [making] sure that parents, when they say, ‘I haven't done anything,’ that we're listening to them and we are giving them the opportunity to defend themselves,” explained Rawlings.

CAPs undergo special training to identify abuse, so their diagnoses wield a lot of power. This was echoed in the Alexander trial. Several medical professionals were asked if they tended to go along with the CAPs assessment.

When asked why, Dr. Charlaya Campbell with Zoe Pediatrics said, “It’s considered the top of the line.” Doctors did say they would speak up if they noticed something that conflicted with that medical opinion, but admitted they weren’t looking for, or running tests to challenge the diagnosis.

That’s a concern to some child welfare advocates because CAPs aren’t just diagnosing the medical problem – they’re declaring how the child got it: abuse. Once that has been discussed, parents feel everyone else, from doctors and DFCS to law enforcement, start to view the case through that lens.

Families who deny the allegation argue child abuse pediatricians make decisions based off a snapshot in time, when to really diagnose and understand the injury, doctors need to look at the whole picture, birth records, and previous medical appointments.

Tracie said two of Parker’s fractures are a perfect example. Radiologists identified them after he went into foster care. The radiologists working with the CAP said they must have missed the fractures the first time around. But Parker’s parents see them as new, unexplained, injuries while out of their custody.

“I do believe that sometimes what is missing for the parents is the ability to have that second opinion from an independent person,” said Rawlings who is not involved in the Alexander case. “We get second medical opinions on lots of things because the decision we're making legally is so, so significant to the child's future.”

Even CAPs don’t seem to understand that in Georgia, that’s easier said than done.

A bitter reality

Dr. Stephen Messner, the Medical Director of Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta’s child abuse program, testified in the Alexander trial. When asked if families could get a second opinion he said, ”unless their parental rights have been terminated, I don’t believe there’s anything preventing them from getting a second opinion.”

Parents impacted would say there are several things preventing that from happening.

“Tarilyn and Tyler couldn't do that because their child had been taken from them. They weren't allowed to take them to doctors or be at any doctor's appointments,” said Tracie Lester. “We asked for second opinions and they come back with that's not needed. That test isn't needed.”

Tracie didn’t get custody until Parker was 8 months old -- six months after the allegations. It was only then that she was able to get more testing. She said most doctors looked at Parker’s medical chart from Children’s and sent them home.

“They do not want to go outside what that child abuse pediatrician said. They don't want to ruffle feathers. They don't want to get involved,” said Tracie.

Prosecutors called several of those doctors during the trial. They said it wasn’t a concern over whether to push back, but a belief that further testing was unnecessary given the test results already provided.

They showed diagrams explaining the type of force involved in various bone breaks and insisted the only cause for a child, Parker’s age, would be abuse. Doctors also testified it takes more than a vitamin D deficiency to get brittle bones.

Tracie did eventually learn Parker had a missing chromosome; it is unclear what impact it could have on Parker’s health. The family also shared with 11Alive Investigates several reports from other medical professionals, offering their opinion on why Parker's injuries were not abuse. A doctor in Boston also told the family it’s likely Parker has Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome.

“Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome is a connective tissue disorder that affects the joints and sockets in your body,” explained Tyler Alexander outside the courthouse.

At trial, other medical professionals stressed there’s no definitive test for children to determine if they have EDS. Either way, prosecutors argued it wouldn’t explain Parker’s injuries.

“Sometimes good people do bad things. Sometimes, they snap. It doesn’t mean they’re not accountable for what they do when they snap,” said Administrative Chief Assistant District Attorney Kate Lenhard who told jurors Parker's GERD likely made him a fussy baby.

Cases like the Alexanders have started to garner national attention from groups like You Are The Power.

“We help small organizations who have been harmed by an overreaching government,” explained YATP’s Georgia Coordinator Ryan Ralston.

He’s helped organize fundraisers, news conferences and launched social media campaigns to raise awareness.

“Our ultimate goal is to make sure all the state of officials are aware of this,” said Ralston. “We want them to understand what is happening in Georgia.”

Back at the Lesters' house, Tracie has pulled out the bubbles. Her grandsons ask Lolly for more. That's the nickname Tracie picked when Parker was born.

Lolly - like lollipop.

“We're thinking of this nickname because grandparents are everything sweet. That's what we're supposed to be. Everything sweet,” said Tracie.

A bit of sweetness, when life could leave you bitter.